February 23, 2012

Allan Sloan is a conscientious columnist with whom I occasionally have serious disagreements. The finances of Social Security is one of those occasions.

Sloan’s Fortune column this week provides one of those occasions. The focus is the deterioration in the near-term projections for Social Security. Sloan compares the 2011 Social Security Trustees report with the 2012 projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and finds a worsening of $300 billion in the projected cash flow of the trust fund over the next five years. He argues that this strengthens the case for measures to shore up the program’s finances. There are three slightly technical points on Sloan’s analysis that are worth making and then one substantive point.

First, Sloan compares sources that use somewhat different assumptions when comparing the Trustees numbers with the CBO numbers. The 2011 CBO numbers would have shown a somewhat worse picture than the 2011 Trustees numbers. If we compare the 2012 CBO numbers with the 2011 CBO numbers we can see the extent to which the situation has deteriorated due to a worsening economic outlook.

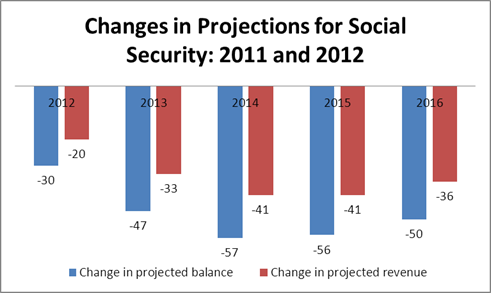

This doesn’t change the picture hugely, but it does make the deterioration somewhat less severe. The difference in the projected shortfall for the years 2012-2016 is $240 billion rather than the $300 billion using the 2011 Trustees numbers as the basis for comparison. (The Disability Trust Fund is projected to be depleted in 2016, so CBO does not project revenue and spending in that year. I have imputed a shortfall of $45 billion, the same as the prior two years.)

A second item worth noting is that the deterioration is mostly on the revenue side. Sloan attributes the problem to higher-than-projected cost-of-living adjustments that resulted from the jump in oil prices. While this is a factor, most of the story is on the revenue side.

Source: CBO 2011 and 2012.

This matters because the main reason that revenue is projected to be lower in 2012 than in 2011 is that unemployment is now projected to be higher and wage growth is projected to be lower. This once again shows the importance for Social Security of having adults in charge of managing the economy. When the economy does badly, Social Security’s finances do badly (repeat 256,000 times).

The third point worth noting in this story is the extent to which the deterioration in the projections from 2011 to 2012 is due to the disability portion of the program. With my imputation for 2016, the worsening finances of disability accounted for $49 billion of the $240 billion deterioration in the program’s projections from 2011 to 2012. This means that a program that receives just 14.5 percent of the program’s revenue accounted for 20.4 percent of the deterioration in finances.

This is not a new story. The cost of the disability program has been rising considerably more rapidly than had previously been projected throughout this downturn. There are not conclusive answers as to why this is the case, but it seems pretty clear that a prolonged period of high unemployment is a big part of the story. In a strong economy, people who have various physical and psychological problems may be able to hold onto their jobs until retirement. (Most of the disabled are older workers.) In a weak economy many of these people may lose their jobs and be unable to find new ones. The moral of the story is again the need to have adults running the economy.

Finally there is the substantive issue about the urgency of a Social Security fix. I see little urgency for two reasons. The first reason is that at a time when we are still down close to 10 million jobs from where the economy should be, the first, second, and third priority of policymakers should be job creation. In principle, Congress and the president can do more than one thing at a time, but this is Washington that we are talking about.

The second reason why I see no urgency for a Social Security fix is that the program is still fundamentally sound. According to the latest projections from CBO we still have more than a quarter-century before the fund will first face a shortfall. Even after that date the program would still be able to pay more than 80 percent of projected benefits, which would be more than current beneficiaries receive.

The eventual fix for Social Security will inevitably involve some mix of revenue increases and benefit cuts. There has been a well-financed campaign over the last few decades to convince the public that the program’s finances are far worse than is in fact the case. (A payroll tax increase equal to one-twentieth of projected wage growth over the next four decades would be more than enough to keep the program fully solvent past the end of the century.)

The lack of confidence in Social Security’s finances created by this misinformation campaign may cause the public to accept much larger cuts than if they realized the program’s true financial state. Therefore it makes sense to delay any major changes in the hope that the public will be better informed about the program in the future. (Peter Peterson will eventually run out of money.)

So the word for the day is “relax” – Social Security is fine for long into the future. Folks should instead spend their time yelling about the lack of adequate stimulus, insufficient measures from the Fed, and an over-valued dollar.

Comments