It’s hardly a surprise to see a column in the Washington Post opinion pages calling for lower federal budget deficits. In spite of the continued weakness of the labor market and the economy, the Washington Post continues to push for less demand, growth, and employment.

Fred Hiatt did the job today by praising Rhode Island Governor Gina Raimondo for cutting public employee pensions, and contrasting these cuts with increased tax cuts and spending at the federal level. Hiatt’s complaint is that Congress agreed to extend tax cuts, which with interest are projected to cost $780 billion over the next decade. This comes to roughly 0.4 percent of GDP over this period.

In a context where the economy is likely to face a shortfall in demand, this addition to the deficit will lead to more growth and jobs, although its impact would be larger if more of the money were committed to items like education and infrastructure or the tax cuts went to lower or middle income people. Assuming a multiplier of 1, the addition to GDP would be approximately 0.4 percent of GDP, implying around 500,000 more jobs. (If the Fed is deliberately blocking growth by raising interest rates, then the tax cuts will not boost growth.)

It is also worth noting that Raimondo’s pension strategy in Rhode Island has meant a windfall for hedge funds, which are now collecting substantial fees from the state’s pension funds. While the Washington Post is generally happy to see cuts to ordinary workers’ pensions and Social Security, it consistently applauds actions, such as the TARP, which give public money to the financial sector.

It’s hardly a surprise to see a column in the Washington Post opinion pages calling for lower federal budget deficits. In spite of the continued weakness of the labor market and the economy, the Washington Post continues to push for less demand, growth, and employment.

Fred Hiatt did the job today by praising Rhode Island Governor Gina Raimondo for cutting public employee pensions, and contrasting these cuts with increased tax cuts and spending at the federal level. Hiatt’s complaint is that Congress agreed to extend tax cuts, which with interest are projected to cost $780 billion over the next decade. This comes to roughly 0.4 percent of GDP over this period.

In a context where the economy is likely to face a shortfall in demand, this addition to the deficit will lead to more growth and jobs, although its impact would be larger if more of the money were committed to items like education and infrastructure or the tax cuts went to lower or middle income people. Assuming a multiplier of 1, the addition to GDP would be approximately 0.4 percent of GDP, implying around 500,000 more jobs. (If the Fed is deliberately blocking growth by raising interest rates, then the tax cuts will not boost growth.)

It is also worth noting that Raimondo’s pension strategy in Rhode Island has meant a windfall for hedge funds, which are now collecting substantial fees from the state’s pension funds. While the Washington Post is generally happy to see cuts to ordinary workers’ pensions and Social Security, it consistently applauds actions, such as the TARP, which give public money to the financial sector.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Brad posted a short note commenting on my paper on rents as the basis for upward redistribution in the last thirty five years. The paper outlines ways in which rents in various areas can explain this upward redistribution, as opposed to the sort of argument advanced by Thomas Piketty that it is some natural process that is inherent to capitalism.

Brad suggested that Piketty would respond by saying that the beneficiaries of this upward redistribution are behind the mechanisms (e.g. stronger and longer patent protection and a bloated financial sector) that have led to this upward redistribution. I agree that this is likely Piketty’s response, but I would raise two points.

First, do we believe that all of these mechanisms were somehow preordained? Was it inevitable that we would have TRIPS, extending and strengthening patent and copyright protection throughout the world? Was there no way to avoid the financial deregulation that gave us too big to fail banks and an explosion of short-term trading and proliferation of new financial instruments? We can look back and know who won these battles, but surely it was possible that some or most of them could have gone the other way.

The other point is how we envision political battles going forward. We know the rich will fight any policy that jeopardizes their wealth and power, but let’s consider two scenarios. On the one hand, we have policies that give shareholders more power to contain CEO pay and proposals to publicly fund clinical trials so that new drugs can be put on the market at generic prices. On the other hand we have a proposal for a global tax on wealth. Which direction has better prospects?

Addendum

Joe Seydl raises a good question in his comment, asking: “who are the selfless activists who are supposed to continuously keep competiton fair?”

The answer is that I am not expecting anyone to be a selfless activist. I am expecting people to act in their own interest. The pharmaceutical companies rip people off by getting longer and stronger patent protection. Doctors rip people off by creating protectionists barriers that restrict supply. The financial industry rips people off on the fees they charge to manage pensions, IRAs, and 401(k)s, and CEOs rip off shareholders by paying themselves exorbitant salaries.

This is not a story that requires selfless activists, but there is a collective action problem. For example, people paying more money for their health care due to high doctors’ pay have to act to remove the protections that get them high pay. The shareholders being ripped off by CEOs have to act to check CEO pay.

Collective action problems are difficult, but the other side has managed to overcome them. They have been able to reduce or eliminate trade barriers that allowed U.S. manufacturing workers to enjoy relatively high wages. The same story applies to the reduction or elimination of agricultural subsidies that have supported small farmers.

The problem for progressives is figuring out how to mobilize people who have a direct stake in leading the efforts to rein in abuses. In the case of the drug companies, the insurance industry would be an obvious suspect. In the case of doctors, nurses and other health care professionals who could do many of the tasks that doctors try to preserve for themselves, would be an obvious group. Also foreign educated physicians who are excluded from the U.S. could make an appeal to all the “free traders” who consider any protectionist barrier a crime against humanity if the beneficiary is a less-educated workers. (Yes, these people are pathetic hypocrites.)

Anyhow, the point of the rent argument is that there is money on the table. We just have to get people to notice the money so that they will take it.

Brad posted a short note commenting on my paper on rents as the basis for upward redistribution in the last thirty five years. The paper outlines ways in which rents in various areas can explain this upward redistribution, as opposed to the sort of argument advanced by Thomas Piketty that it is some natural process that is inherent to capitalism.

Brad suggested that Piketty would respond by saying that the beneficiaries of this upward redistribution are behind the mechanisms (e.g. stronger and longer patent protection and a bloated financial sector) that have led to this upward redistribution. I agree that this is likely Piketty’s response, but I would raise two points.

First, do we believe that all of these mechanisms were somehow preordained? Was it inevitable that we would have TRIPS, extending and strengthening patent and copyright protection throughout the world? Was there no way to avoid the financial deregulation that gave us too big to fail banks and an explosion of short-term trading and proliferation of new financial instruments? We can look back and know who won these battles, but surely it was possible that some or most of them could have gone the other way.

The other point is how we envision political battles going forward. We know the rich will fight any policy that jeopardizes their wealth and power, but let’s consider two scenarios. On the one hand, we have policies that give shareholders more power to contain CEO pay and proposals to publicly fund clinical trials so that new drugs can be put on the market at generic prices. On the other hand we have a proposal for a global tax on wealth. Which direction has better prospects?

Addendum

Joe Seydl raises a good question in his comment, asking: “who are the selfless activists who are supposed to continuously keep competiton fair?”

The answer is that I am not expecting anyone to be a selfless activist. I am expecting people to act in their own interest. The pharmaceutical companies rip people off by getting longer and stronger patent protection. Doctors rip people off by creating protectionists barriers that restrict supply. The financial industry rips people off on the fees they charge to manage pensions, IRAs, and 401(k)s, and CEOs rip off shareholders by paying themselves exorbitant salaries.

This is not a story that requires selfless activists, but there is a collective action problem. For example, people paying more money for their health care due to high doctors’ pay have to act to remove the protections that get them high pay. The shareholders being ripped off by CEOs have to act to check CEO pay.

Collective action problems are difficult, but the other side has managed to overcome them. They have been able to reduce or eliminate trade barriers that allowed U.S. manufacturing workers to enjoy relatively high wages. The same story applies to the reduction or elimination of agricultural subsidies that have supported small farmers.

The problem for progressives is figuring out how to mobilize people who have a direct stake in leading the efforts to rein in abuses. In the case of the drug companies, the insurance industry would be an obvious suspect. In the case of doctors, nurses and other health care professionals who could do many of the tasks that doctors try to preserve for themselves, would be an obvious group. Also foreign educated physicians who are excluded from the U.S. could make an appeal to all the “free traders” who consider any protectionist barrier a crime against humanity if the beneficiary is a less-educated workers. (Yes, these people are pathetic hypocrites.)

Anyhow, the point of the rent argument is that there is money on the table. We just have to get people to notice the money so that they will take it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In its usual bipartisan way the Post took even-handed swipes at Republican Representative Jeb Hensarling and Bernie Sanders, a senator and candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, over their criticisms of the Federal Reserve Board. Never mind that Hensarling’s criticisms were over the Fed’s failure to raise interest rates to prevent hyper-inflation over the last five years, while Sanders’ criticism was over the fact that the Fed’s recent rate hike will slow growth and the rate of job creation. In Washington post bi-partisan land, both are equally damnable offenses.

But what is even more striking is the Post’s ability to treat the Fed as a neutral party when the evidence is so overwhelming in the opposite direction. The majority of the Fed’s 12 district bank presidents have long been pushing for a rate hike. While there are some doves among this group, most notably Charles Evans, the Chicago bank president, and Narayana Kocherlakota, the departing president of the Minneapolis bank, most of this group has publicly pushed for higher rate hikes for some time. By contrast, the governors who are appointed through the democratic process, have been far more cautious about raising rates.

It should raise serious concerns that the bank presidents, who are appointed through a process dominated by the banking industry, has such a different perspective on the best path forward for monetary policy. With only five of the seven governor slots currently filled, there are as many bank presidents with voting seats on the Fed’s Open Market Committee as governors. In total, the governors are outnumbered at meetings by a ratio of twelve to five.

Any serious discussion of Fed policy would note that the banking industry appears to have a grossly disproportionate say in the country’s monetary policy. Furthermore, it seems determined to use that influence to push the Fed on a path that slows growth and reduces the rate of job creation. The Post somehow missed this story or at least would prefer that the rest of us not take notice.

In its usual bipartisan way the Post took even-handed swipes at Republican Representative Jeb Hensarling and Bernie Sanders, a senator and candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, over their criticisms of the Federal Reserve Board. Never mind that Hensarling’s criticisms were over the Fed’s failure to raise interest rates to prevent hyper-inflation over the last five years, while Sanders’ criticism was over the fact that the Fed’s recent rate hike will slow growth and the rate of job creation. In Washington post bi-partisan land, both are equally damnable offenses.

But what is even more striking is the Post’s ability to treat the Fed as a neutral party when the evidence is so overwhelming in the opposite direction. The majority of the Fed’s 12 district bank presidents have long been pushing for a rate hike. While there are some doves among this group, most notably Charles Evans, the Chicago bank president, and Narayana Kocherlakota, the departing president of the Minneapolis bank, most of this group has publicly pushed for higher rate hikes for some time. By contrast, the governors who are appointed through the democratic process, have been far more cautious about raising rates.

It should raise serious concerns that the bank presidents, who are appointed through a process dominated by the banking industry, has such a different perspective on the best path forward for monetary policy. With only five of the seven governor slots currently filled, there are as many bank presidents with voting seats on the Fed’s Open Market Committee as governors. In total, the governors are outnumbered at meetings by a ratio of twelve to five.

Any serious discussion of Fed policy would note that the banking industry appears to have a grossly disproportionate say in the country’s monetary policy. Furthermore, it seems determined to use that influence to push the Fed on a path that slows growth and reduces the rate of job creation. The Post somehow missed this story or at least would prefer that the rest of us not take notice.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT reported on the reaction in financial markets to the Federal Reserve Board’s decision to raise interest rates on Wednesday. The piece notes the generally calm reaction, but also indicates there continue to be some concern about asset bubbles. It comments:

“Regulators have pointed to a number of worrisome signs in recent weeks. A federal agency said on Tuesday that credit risks were ‘elevated and rising’ for American corporations and many foreign borrowers, even as investors are demanding significantly higher interest rates on junk bonds and foreign debt. The report, by the Office of Financial Research, however, said overall risks to stability remained ‘moderate.'”

It is worth distinguishing the possible bubble in junk bonds and foreign debt from the stock and housing bubbles whose collapse brought on the last two recessions. Both the stock and housing bubbles were driving the economy. They directly generated large amounts of demand through investment spending in the case of the stock bubble and residential construction spending in the case of the housing bubble. Both bubbles also led to consumption booms, as households increased spending based on the ephemeral wealth generated by these bubbles. For this reason, it was 100 percent predictable that the collapse of the bubbles would lead to recessions.

The current bubbles in junk bonds and foreign debt are not in any way driving the economy. Presumably we are seeing somewhat more investment as a result of the fact that uncreditworthy companies were able to borrow at a low cost, but there is no notable boom in such investment. Similarly, if foreign borrowers have a harder time getting access to credit, it may be bad news for them, but the impact on the U.S. economy will be limited.

If some banks or other financial institutions have over committed themselves in these areas, the plunge in prices may threaten their survival. This could lead to some late nights for folks at the Fed and other regulators, but it will not pose a major risk to the economy.

The NYT reported on the reaction in financial markets to the Federal Reserve Board’s decision to raise interest rates on Wednesday. The piece notes the generally calm reaction, but also indicates there continue to be some concern about asset bubbles. It comments:

“Regulators have pointed to a number of worrisome signs in recent weeks. A federal agency said on Tuesday that credit risks were ‘elevated and rising’ for American corporations and many foreign borrowers, even as investors are demanding significantly higher interest rates on junk bonds and foreign debt. The report, by the Office of Financial Research, however, said overall risks to stability remained ‘moderate.'”

It is worth distinguishing the possible bubble in junk bonds and foreign debt from the stock and housing bubbles whose collapse brought on the last two recessions. Both the stock and housing bubbles were driving the economy. They directly generated large amounts of demand through investment spending in the case of the stock bubble and residential construction spending in the case of the housing bubble. Both bubbles also led to consumption booms, as households increased spending based on the ephemeral wealth generated by these bubbles. For this reason, it was 100 percent predictable that the collapse of the bubbles would lead to recessions.

The current bubbles in junk bonds and foreign debt are not in any way driving the economy. Presumably we are seeing somewhat more investment as a result of the fact that uncreditworthy companies were able to borrow at a low cost, but there is no notable boom in such investment. Similarly, if foreign borrowers have a harder time getting access to credit, it may be bad news for them, but the impact on the U.S. economy will be limited.

If some banks or other financial institutions have over committed themselves in these areas, the plunge in prices may threaten their survival. This could lead to some late nights for folks at the Fed and other regulators, but it will not pose a major risk to the economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In an article on the Federal Reserve Board’s decision to raise interest rates, the Washington Post referred to the 2.4 percent median growth forecast of the Fed’s Open Market Committee. It might have worth mentioning that the Fed’s forecasts have consistently been higher than actual growth. For example, last December their median forecast for growth in 2015 was 2.8 percent. It now appears growth will be around 2.2 percent for the year. The Fed was not out of line with other forecasts. For example the Congressional Budget Office, which quite explicitly tries to be near the middle of major forecasts, forecast 2.9 percent growth for 2015.

In an article on the Federal Reserve Board’s decision to raise interest rates, the Washington Post referred to the 2.4 percent median growth forecast of the Fed’s Open Market Committee. It might have worth mentioning that the Fed’s forecasts have consistently been higher than actual growth. For example, last December their median forecast for growth in 2015 was 2.8 percent. It now appears growth will be around 2.2 percent for the year. The Fed was not out of line with other forecasts. For example the Congressional Budget Office, which quite explicitly tries to be near the middle of major forecasts, forecast 2.9 percent growth for 2015.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Most people realize that politicians don’t always give the true explanation for their actions. For example, few politicians are likely to say that they vote against gun control measures because the NRA is a powerful lobby that could derail their political career, even if this is the real reason for their vote. They are more likely to claim they vote against gun control measures because of their belief in the rights of gun owners.

While most people may recognize this fact, apparently the folks at the NYT do not. In an article on the new budget deal it noted that several Democrats had joined with Republicans in suspending the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) tax on medical devices through 2017. The piece told readers:

“Republicans said the device tax discouraged the development and sales of innovative, lifesaving medical technology. Some Democrats from states with thriving medical technology companies agreed.”

Of course the NYT does not know that the Democrats who voted to suspend the tax agreed with the claim that it would discourage the development of new technologies. They may have just voted against the tax because the companies in their states and districts are powerful lobbies.

The economics of the medical device industry are similar to the economics of the prescription drug industry. Companies have large research costs, but then are able to sell devices for a markup of several hundred or several thousand percent above their marginal cost. By giving more people access to health care, the ACA was increasing the demand for medical devices and therefore increasing the number of devices that could be sold at high markups, creating a windfall for the industry. The purpose of the tax was to take back some of this windfall.

Opponents of the tax may actually disagree with this logic. Alternatively, they may just be doing the bidding of a politically powerful industry. It is worth noting that the Obama administration did not propose a similar tax on pharmaceuticals, even though the logic would be identical. The pharmaceutical industry is of course even bigger and more powerful than the medical device industry.

On the topic of the article itself, we are told in the first sentence:

“Republican and Democratic negotiators in the House clinched a deal late Tuesday on a $1.1 trillion spending bill and a huge package of tax breaks.”

A denominator would be helpful here. Most of the package covers the next two years, a period in which the government is projected to spend a bit less than $8 trillion.

Most people realize that politicians don’t always give the true explanation for their actions. For example, few politicians are likely to say that they vote against gun control measures because the NRA is a powerful lobby that could derail their political career, even if this is the real reason for their vote. They are more likely to claim they vote against gun control measures because of their belief in the rights of gun owners.

While most people may recognize this fact, apparently the folks at the NYT do not. In an article on the new budget deal it noted that several Democrats had joined with Republicans in suspending the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) tax on medical devices through 2017. The piece told readers:

“Republicans said the device tax discouraged the development and sales of innovative, lifesaving medical technology. Some Democrats from states with thriving medical technology companies agreed.”

Of course the NYT does not know that the Democrats who voted to suspend the tax agreed with the claim that it would discourage the development of new technologies. They may have just voted against the tax because the companies in their states and districts are powerful lobbies.

The economics of the medical device industry are similar to the economics of the prescription drug industry. Companies have large research costs, but then are able to sell devices for a markup of several hundred or several thousand percent above their marginal cost. By giving more people access to health care, the ACA was increasing the demand for medical devices and therefore increasing the number of devices that could be sold at high markups, creating a windfall for the industry. The purpose of the tax was to take back some of this windfall.

Opponents of the tax may actually disagree with this logic. Alternatively, they may just be doing the bidding of a politically powerful industry. It is worth noting that the Obama administration did not propose a similar tax on pharmaceuticals, even though the logic would be identical. The pharmaceutical industry is of course even bigger and more powerful than the medical device industry.

On the topic of the article itself, we are told in the first sentence:

“Republican and Democratic negotiators in the House clinched a deal late Tuesday on a $1.1 trillion spending bill and a huge package of tax breaks.”

A denominator would be helpful here. Most of the package covers the next two years, a period in which the government is projected to spend a bit less than $8 trillion.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a column by Jim Parrot and Mark Zandi on reforming Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. (Jim Parrott is a senior fellow at the Urban Institute and the owner of Falling Creek Advisors, a financial consulting firm. Mark Zandi is the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.) The article argues that the problem with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was that they were considered too big to fail. It therefore puts forward the case for ending their monopoly on issuing government guaranteed mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

This argument seriously misrepresents the issues with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The real problem was that they issued trillions of dollars in MBS that were implicitly backed up by the government. At the time they failed in the summer of 2008, the generally held view in financial circles was that the government would be obligated to honor their MBS regardless of whether or not it kept Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in business. In other words, the issue was not the $180 billion bailout (about which elite types routinely and misleadingly say we made a profit) the issue was the huge amount of bad MBS that helped propel the housing bubble.

This was a direct result of the perverse incentives created by a system where private shareholders and top executives stood to profit by passing risk off to the government. This incentive does not exist today. This incentive does not exist today. (The line is repeated because policy folks have a hard time understanding it.) As long as Fannie and Freddie are essentially public companies, that do not offer high returns to shareholders and pay outlandish salaries to CEOs, no one has incentive to take excessive risks.

This changes if we allow private banks to issue mortgage backed securities with the guarantee of the government. This would mean that Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and the rest would be able to issue the same sort of subprime MBS they did in the bubble years with assurance that even in a worst case scenario the government would reimbursement investors for almost the full value of their investment. This is a great recipe for pumping up financial sector profits and another housing bubble. It does not make sense as public policy.

Addendum

This piece provides some background on the most likely reform of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

The NYT had a column by Jim Parrot and Mark Zandi on reforming Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. (Jim Parrott is a senior fellow at the Urban Institute and the owner of Falling Creek Advisors, a financial consulting firm. Mark Zandi is the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.) The article argues that the problem with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was that they were considered too big to fail. It therefore puts forward the case for ending their monopoly on issuing government guaranteed mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

This argument seriously misrepresents the issues with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The real problem was that they issued trillions of dollars in MBS that were implicitly backed up by the government. At the time they failed in the summer of 2008, the generally held view in financial circles was that the government would be obligated to honor their MBS regardless of whether or not it kept Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in business. In other words, the issue was not the $180 billion bailout (about which elite types routinely and misleadingly say we made a profit) the issue was the huge amount of bad MBS that helped propel the housing bubble.

This was a direct result of the perverse incentives created by a system where private shareholders and top executives stood to profit by passing risk off to the government. This incentive does not exist today. This incentive does not exist today. (The line is repeated because policy folks have a hard time understanding it.) As long as Fannie and Freddie are essentially public companies, that do not offer high returns to shareholders and pay outlandish salaries to CEOs, no one has incentive to take excessive risks.

This changes if we allow private banks to issue mortgage backed securities with the guarantee of the government. This would mean that Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and the rest would be able to issue the same sort of subprime MBS they did in the bubble years with assurance that even in a worst case scenario the government would reimbursement investors for almost the full value of their investment. This is a great recipe for pumping up financial sector profits and another housing bubble. It does not make sense as public policy.

Addendum

This piece provides some background on the most likely reform of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson again gives us his data free explanation for the weak recovery in his Monday column. He contrasts the current weak recovery with the strong recovery of the eighties. He notes the Fed’s efforts to boost the economy in both periods, then tells readers:

“In the 1980s and ’90s, consumers and businesses were eager to spend. The Fed accommodated that demand but did not create it. By contrast, consumers and businesses now are conditioned to be wary. Having lived through events — the financial panic and crushing recession — that supposedly could not happen, they are reluctant spenders. The Fed can try to ease their caution but cannot systematically eliminate it.”

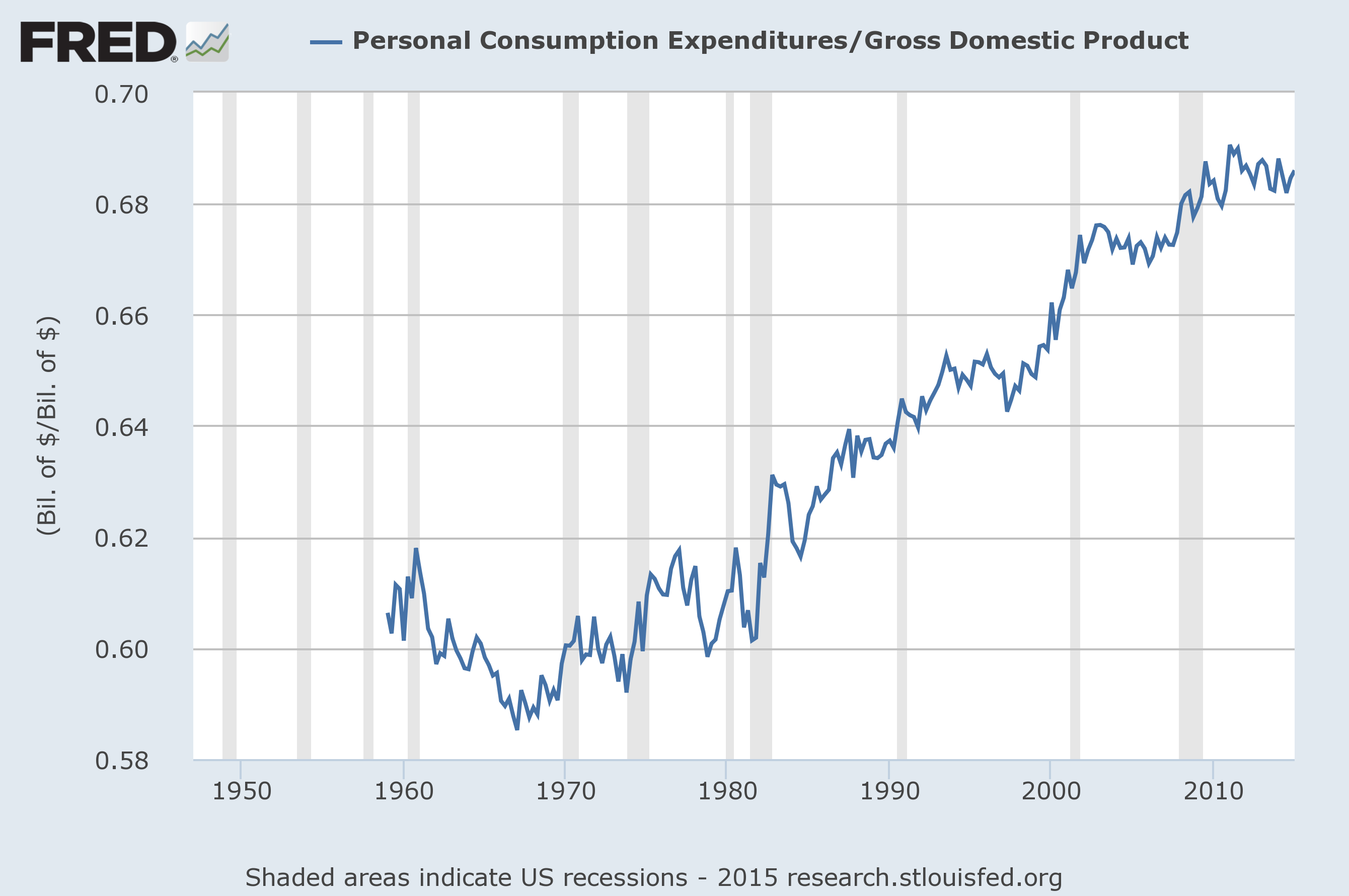

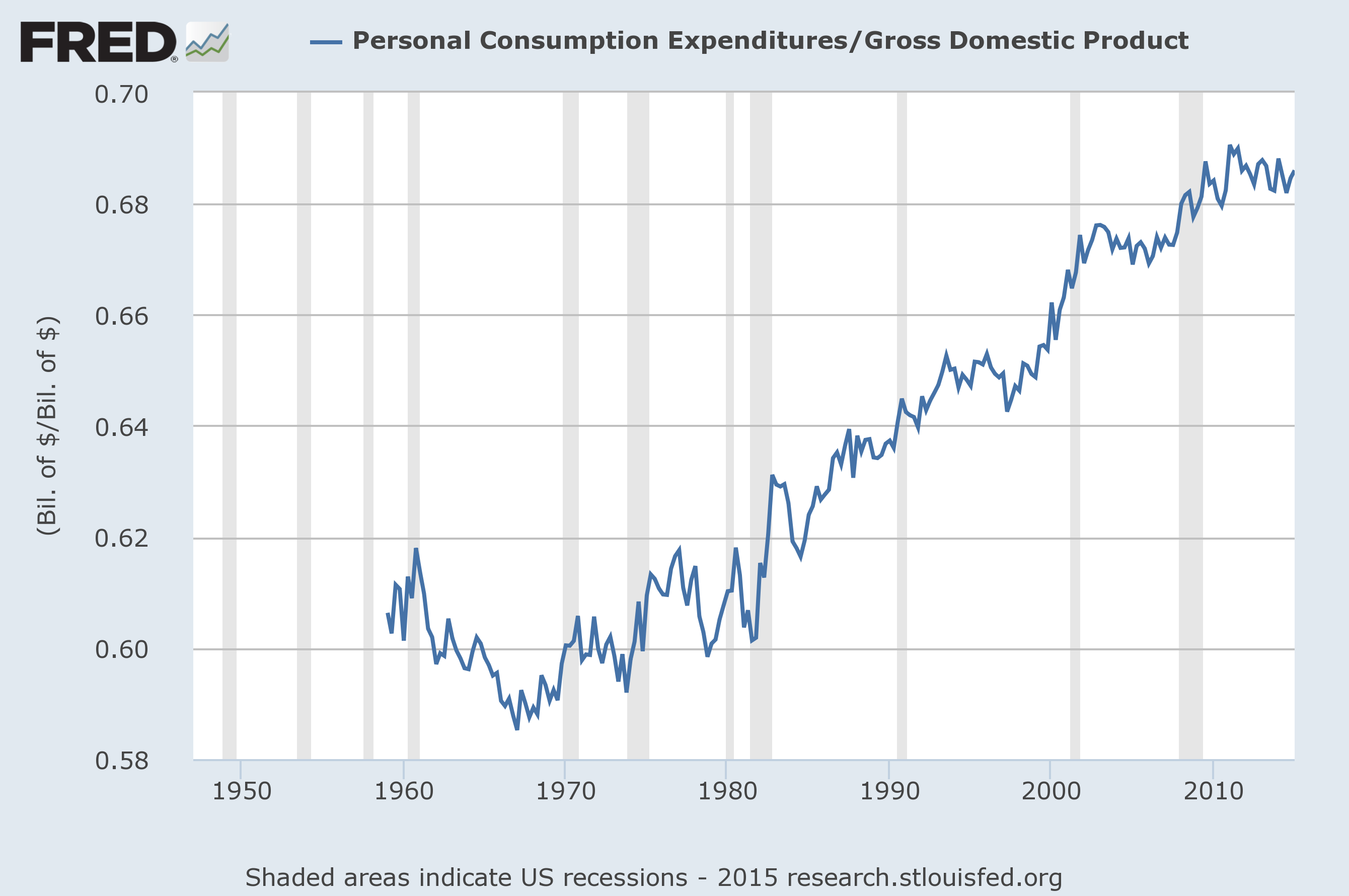

The problem with this story is that consumers are spending and businesses are investing. Consumption is at a near record high as a share of GDP. It is only slightly below the peak reached in the housing bubble.

Non-residential investment as a share of GDP is somewhat below the peaks of the tech bubble in the late 1990s, but is higher than during the eighties boom. The explanation for the weaker recovery is that there was an enormous excess supply of housing coming out of the bubble. This kept construction rates very low ever since the collapse of the bubble. By contrast, the Volcker recession led to a plunge in housing construction, which created a huge amount of pent-up demand for when the Fed lowered interest rates. (The trade deficit, at 3.0 percent of GDP or $500 billion annually, also creates a huge hole in demand that is not easily filled.)

The other major difference between the current recovery and the 1980s was that the structural budget deficit was expanding rapidly in that recovery. In the current recovery it has been contracting rapidly.

In short, there is a very simple story as to why this recovery has been weak and has nothing to do with the factors that Samuelson keeps highlighting.

Robert Samuelson again gives us his data free explanation for the weak recovery in his Monday column. He contrasts the current weak recovery with the strong recovery of the eighties. He notes the Fed’s efforts to boost the economy in both periods, then tells readers:

“In the 1980s and ’90s, consumers and businesses were eager to spend. The Fed accommodated that demand but did not create it. By contrast, consumers and businesses now are conditioned to be wary. Having lived through events — the financial panic and crushing recession — that supposedly could not happen, they are reluctant spenders. The Fed can try to ease their caution but cannot systematically eliminate it.”

The problem with this story is that consumers are spending and businesses are investing. Consumption is at a near record high as a share of GDP. It is only slightly below the peak reached in the housing bubble.

Non-residential investment as a share of GDP is somewhat below the peaks of the tech bubble in the late 1990s, but is higher than during the eighties boom. The explanation for the weaker recovery is that there was an enormous excess supply of housing coming out of the bubble. This kept construction rates very low ever since the collapse of the bubble. By contrast, the Volcker recession led to a plunge in housing construction, which created a huge amount of pent-up demand for when the Fed lowered interest rates. (The trade deficit, at 3.0 percent of GDP or $500 billion annually, also creates a huge hole in demand that is not easily filled.)

The other major difference between the current recovery and the 1980s was that the structural budget deficit was expanding rapidly in that recovery. In the current recovery it has been contracting rapidly.

In short, there is a very simple story as to why this recovery has been weak and has nothing to do with the factors that Samuelson keeps highlighting.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In case you were wondering about the importance of a $100 billion a year, non-binding commitment, it’s roughly 0.25 percent of rich countries’ $40 trillion annual GDP (about 6 percent of what the U.S. spends on the military). This counts the U.S., European Union, Japan, Canada, and Australia as rich countries. If China is included in that list, the commitment would be less than 0.2 percent of GDP.

Addendum

I see my comment on military spending here created a bit of confusion. I was looking at the U.S. share of the commitment, 0.25 percent of its GDP and comparing it to the roughly 4.0 percent of GDP it spends on the military. That comes to 6 percent. I was not referring to the whole $100 billion.

In case you were wondering about the importance of a $100 billion a year, non-binding commitment, it’s roughly 0.25 percent of rich countries’ $40 trillion annual GDP (about 6 percent of what the U.S. spends on the military). This counts the U.S., European Union, Japan, Canada, and Australia as rich countries. If China is included in that list, the commitment would be less than 0.2 percent of GDP.

Addendum

I see my comment on military spending here created a bit of confusion. I was looking at the U.S. share of the commitment, 0.25 percent of its GDP and comparing it to the roughly 4.0 percent of GDP it spends on the military. That comes to 6 percent. I was not referring to the whole $100 billion.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Okay, this one is a bit personal, but it reflects a larger issue. The Pew Research Center just put out a study showing that a declining share of the U.S. population is middle class, with greater percentages falling both in the upper and lower income category than was the case four decades ago. Washington Post columnist Dan Balz touted this declining middle class story as an explanation for the rise of Donald Trump.

The problem here is that there is nothing new in the Pew study. My friend and former boss, Larry Mishel, has been writing about wage stagnation for a quarter century at the Economic Policy Institute. The biannual volume, The State of Working America, has been tracking the pattern of stagnating middle class wages and family income (for the non-elderly middle class, income is wages) since 1990.

The Pew study added nothing new to this research. They simply constructed an arbitrary definition of middle class and found that fewer families fall within it.

Perhaps having a high budget “centrist” outfit like Pew tout this finding is the only way to get a centrist Washington Post columnist like Balz to pay attention, but it is a bit annoying when we see someone touted for discovering what was already well-known. Oh well, at least it creates good-paying jobs for people without discernible skills.

Okay, this one is a bit personal, but it reflects a larger issue. The Pew Research Center just put out a study showing that a declining share of the U.S. population is middle class, with greater percentages falling both in the upper and lower income category than was the case four decades ago. Washington Post columnist Dan Balz touted this declining middle class story as an explanation for the rise of Donald Trump.

The problem here is that there is nothing new in the Pew study. My friend and former boss, Larry Mishel, has been writing about wage stagnation for a quarter century at the Economic Policy Institute. The biannual volume, The State of Working America, has been tracking the pattern of stagnating middle class wages and family income (for the non-elderly middle class, income is wages) since 1990.

The Pew study added nothing new to this research. They simply constructed an arbitrary definition of middle class and found that fewer families fall within it.

Perhaps having a high budget “centrist” outfit like Pew tout this finding is the only way to get a centrist Washington Post columnist like Balz to pay attention, but it is a bit annoying when we see someone touted for discovering what was already well-known. Oh well, at least it creates good-paying jobs for people without discernible skills.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión