Alan Sloan and Cezary Podkul have a piece in ProPublica that tries to explain the origins of the serious pension shortfalls in Chicago, Illinois, and several other state and local governments. The basic story is that governments went many years without making required contributions, which eventually leads to a serious shortfall.

However, there is another part of this story which is worth adding. In the late 1990s, most pensions were viewed as very well funded. This was due to the extraordinary run-up in stock prices. Many state and local governments drastically cut back their contributions to their pensions since they saw little need. The stock market was doing it for them.

The problem was that the bubble burst (which bubbles do). When the bubble burst over the period 2000–2002, it made pensions appear much less well funded. However, the bursting also led to a recession which worsened the budget situation of governments across the country. State and local governments suddenly had to make much larger pension contributions at a time when they faced large deficits. Not surprisingly, many chose to instead stick their heads in the sand and pray that the bubble would reinflate.

It is worth including this history because it points to the sort of problems created by asset bubbles like the stock and housing bubbles. The conventional wisdom at the time, espoused by folks like Alan Greenspan and the Clinton administration, was that bubbles were no big deal. Greenspan argued the best thing to do was just let bubbles run their course and then pick up the pieces. The pension problems now being faced by state and local governments across the country are among the pieces.

Alan Sloan and Cezary Podkul have a piece in ProPublica that tries to explain the origins of the serious pension shortfalls in Chicago, Illinois, and several other state and local governments. The basic story is that governments went many years without making required contributions, which eventually leads to a serious shortfall.

However, there is another part of this story which is worth adding. In the late 1990s, most pensions were viewed as very well funded. This was due to the extraordinary run-up in stock prices. Many state and local governments drastically cut back their contributions to their pensions since they saw little need. The stock market was doing it for them.

The problem was that the bubble burst (which bubbles do). When the bubble burst over the period 2000–2002, it made pensions appear much less well funded. However, the bursting also led to a recession which worsened the budget situation of governments across the country. State and local governments suddenly had to make much larger pension contributions at a time when they faced large deficits. Not surprisingly, many chose to instead stick their heads in the sand and pray that the bubble would reinflate.

It is worth including this history because it points to the sort of problems created by asset bubbles like the stock and housing bubbles. The conventional wisdom at the time, espoused by folks like Alan Greenspan and the Clinton administration, was that bubbles were no big deal. Greenspan argued the best thing to do was just let bubbles run their course and then pick up the pieces. The pension problems now being faced by state and local governments across the country are among the pieces.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Do newspapers like the NYT test applicants for reporting jobs on their ability to read minds? It seems they must, since so many of them seem to have this skill. Today’s article on the Senate’s approval of a motion to debate fast-track authority at several points told readers what various actors think or believe.

My favorite assessment of inner thoughts was in reference to demands that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) include currency rules:

“But the White House fears that making the accelerated authority contingent on currency policy alterations could scare important partners from the negotiating table, including Japan, the second-largest Trans-Pacific partner.”

If we assume that NYT reporters do not actually read minds, this statement means that someone at the White House (is there a reason for anonymity?) said that they feared currency rules would scare countries away from the negotiating table. As a practical matter, the United States would undoubtedly have to make concessions on other issues in order to get Japan and other countries to agree to currency rules.

Such concessions might mean that the TPP would end up being less beneficial to companies like Nike, Boeing, and Pfizer, which would reduce their interest in the pact. However in any serious assessment the issue is whether the TPP ends up being less corporate friendly as a result of currency rules, not whether the possibility of such a deal would disappear. Of course it is possible that the Obama administration would not have an interest in pursuing a trade deal that was less friendly to large corporations who are major campaign contributors.

It is also worth noting that many large U.S. corporations would actually be opposed to a reduction in the value of the dollar against other currencies. Companies like Walmart and GE, that depend on low cost imports, would lose much of their competitive advantage if the price of the Chinese yuan and other currencies rose against the dollar.

Do newspapers like the NYT test applicants for reporting jobs on their ability to read minds? It seems they must, since so many of them seem to have this skill. Today’s article on the Senate’s approval of a motion to debate fast-track authority at several points told readers what various actors think or believe.

My favorite assessment of inner thoughts was in reference to demands that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) include currency rules:

“But the White House fears that making the accelerated authority contingent on currency policy alterations could scare important partners from the negotiating table, including Japan, the second-largest Trans-Pacific partner.”

If we assume that NYT reporters do not actually read minds, this statement means that someone at the White House (is there a reason for anonymity?) said that they feared currency rules would scare countries away from the negotiating table. As a practical matter, the United States would undoubtedly have to make concessions on other issues in order to get Japan and other countries to agree to currency rules.

Such concessions might mean that the TPP would end up being less beneficial to companies like Nike, Boeing, and Pfizer, which would reduce their interest in the pact. However in any serious assessment the issue is whether the TPP ends up being less corporate friendly as a result of currency rules, not whether the possibility of such a deal would disappear. Of course it is possible that the Obama administration would not have an interest in pursuing a trade deal that was less friendly to large corporations who are major campaign contributors.

It is also worth noting that many large U.S. corporations would actually be opposed to a reduction in the value of the dollar against other currencies. Companies like Walmart and GE, that depend on low cost imports, would lose much of their competitive advantage if the price of the Chinese yuan and other currencies rose against the dollar.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Everyone knows that the Washington Post supports the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), but does it really have to resort to name calling in its news pages to refer to people who disagree with its position? That’s what readers of its front page piece on the Senate vote to block the discussion of a bill authorizing a fast-track are wondering.

The piece referred to Senator Sherrod Brown and other staunch opponents of TPP in its current form as “anti-trade hard-liners.” Of course Senator Brown and his allies are not opponents of trade, they do not advocate autarky. The correct way to refer to these people would have been “anti-TPP.” Given the concern of newspapers over space, in addition to being more accurate, this also would have saved the paper two letters.

The use of the term “hard-liner” is also questionable. Are the strong supporters of TPP ever referred to as “hard-liners?” If not, then it can be argued that the use of phrase in reference to Senator Brown and his allies is more pejorative than descriptive.

Everyone knows that the Washington Post supports the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), but does it really have to resort to name calling in its news pages to refer to people who disagree with its position? That’s what readers of its front page piece on the Senate vote to block the discussion of a bill authorizing a fast-track are wondering.

The piece referred to Senator Sherrod Brown and other staunch opponents of TPP in its current form as “anti-trade hard-liners.” Of course Senator Brown and his allies are not opponents of trade, they do not advocate autarky. The correct way to refer to these people would have been “anti-TPP.” Given the concern of newspapers over space, in addition to being more accurate, this also would have saved the paper two letters.

The use of the term “hard-liner” is also questionable. Are the strong supporters of TPP ever referred to as “hard-liners?” If not, then it can be argued that the use of phrase in reference to Senator Brown and his allies is more pejorative than descriptive.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is what readers of the NYT must be wondering. According to the NYT, the White House strongly objected to a bill that would be attached to fast-track authority which would require the government to impose tariffs to offset the effect of currency management by other countries. (If a country deliberately reduces the value of their currency against the dollar by 10 percent, it has the same impact as imposing a tariff of the same size and providing a 10 percent subsidy on its exports.)

The article notes that Commerce Secretary Penny Pritzker called it “a terrible idea,” and then tells readers:

“Josh Earnest, the White House press secretary, said any measure to counter a foreign power’s currency policies could backfire, undermining the Federal Reserve Board, which uses the flow of currency to tighten or loosen economic growth in the United States.”

This assertion is bizarre because the Fed never intervenes in the currency market to tighten or loosen economic growth in the United States. Its standard tools involve raising or lowering the overnight interest rate and more recently trying to reduce long-term interest rates directly by buying up large amounts of government bonds or mortgage backed securities. These policy tools would not be affected by rules that limited central bank interventions in currency markets.

That is what readers of the NYT must be wondering. According to the NYT, the White House strongly objected to a bill that would be attached to fast-track authority which would require the government to impose tariffs to offset the effect of currency management by other countries. (If a country deliberately reduces the value of their currency against the dollar by 10 percent, it has the same impact as imposing a tariff of the same size and providing a 10 percent subsidy on its exports.)

The article notes that Commerce Secretary Penny Pritzker called it “a terrible idea,” and then tells readers:

“Josh Earnest, the White House press secretary, said any measure to counter a foreign power’s currency policies could backfire, undermining the Federal Reserve Board, which uses the flow of currency to tighten or loosen economic growth in the United States.”

This assertion is bizarre because the Fed never intervenes in the currency market to tighten or loosen economic growth in the United States. Its standard tools involve raising or lowering the overnight interest rate and more recently trying to reduce long-term interest rates directly by buying up large amounts of government bonds or mortgage backed securities. These policy tools would not be affected by rules that limited central bank interventions in currency markets.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In keeping with the Washington elite’s practice that it is fine to say any nutty thing in the world to push a trade, Nike promised to create 10,000 jobs in the United States if the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) passes. As Post reporter Lydia DePillis notes, this is a dubious promise.

Her piece notes that Nike relies almost exclusively on foreign manufacturers for its products. Furthermore, it continues to go in the direction of more outsourcing as one of its suppliers just announced that it was closing a plant in Maine and replacing it with production in Honduras. Given that new facilities are highly automated, it is unlikely that even if Nike brought some production back to the United States it would result in the creation of 10,000 new jobs.

But the Nike claim largely went unexamined, other than this piece by DePillis. This is part of a pattern in which major media outlets treat any nonsense said in favor of a trade agreement as being true. This is why they don’t challenge people who claim that we get jobs by increasing exports, even if the exports are car parts to an assembly plant in Mexico that replaced a plant located in Ohio. It is also why they repeatedly describe the TPP as “massive” and “huge” based on the size of the economies included in the deal, even though most of the countries in the pact already have trade deals with the United States, meaning that the TPP will have little actual effect on their trade with the U.S. (It may affect domestic regulation in those countries.)

In keeping with the Washington elite’s practice that it is fine to say any nutty thing in the world to push a trade, Nike promised to create 10,000 jobs in the United States if the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) passes. As Post reporter Lydia DePillis notes, this is a dubious promise.

Her piece notes that Nike relies almost exclusively on foreign manufacturers for its products. Furthermore, it continues to go in the direction of more outsourcing as one of its suppliers just announced that it was closing a plant in Maine and replacing it with production in Honduras. Given that new facilities are highly automated, it is unlikely that even if Nike brought some production back to the United States it would result in the creation of 10,000 new jobs.

But the Nike claim largely went unexamined, other than this piece by DePillis. This is part of a pattern in which major media outlets treat any nonsense said in favor of a trade agreement as being true. This is why they don’t challenge people who claim that we get jobs by increasing exports, even if the exports are car parts to an assembly plant in Mexico that replaced a plant located in Ohio. It is also why they repeatedly describe the TPP as “massive” and “huge” based on the size of the economies included in the deal, even though most of the countries in the pact already have trade deals with the United States, meaning that the TPP will have little actual effect on their trade with the U.S. (It may affect domestic regulation in those countries.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

David Brooks used the victory of the Conservatives in the United Kingdom to celebrate the “center-right moment” in his column this morning. To make his case he largely creates a caricature of the left to argue for the greater wisdom of the center-right. He tells readers:

“Over the past few years, left-of-center economic policy has moved from opportunity progressivism to redistributionist progressivism. Opportunity progressivism is associated with Bill Clinton and Tony Blair in the 1990s and Mayor Rahm Emanuel of Chicago today. This tendency actively uses government power to give people access to markets, through support for community colleges, infrastructure and training programs and the like, but it doesn’t interfere that much in the market and hesitates before raising taxes.

“This tendency has been politically successful. Clinton and Blair had long terms. This year, Emanuel won by 12 percentage points against the more progressive candidate, Chuy Garcia, even in a city with a disproportionate number of union households.

“Redistributionist progressivism more aggressively raises taxes to shift money down the income scale, opposes trade treaties and meddles more in the marketplace. This tendency has won elections in Massachusetts (Elizabeth Warren) and New York City (Bill de Blasio) but not in many other places.”

For political purposes it is undoubtedly advantageous to imply that the “opportunity” progressives favored the market more than the “redistributionist progressives,” but it is not true. Taking the case of President Clinton, he promoted trade agreements that deliberately placed manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world, while maintaining or increasing the protections for highly paid professionals like doctors and lawyers. This had the predicted and actual effect of raising the incomes of those at the top at the expense of those at the middle and bottom. This upward redistribution was not due to market forces, but to policy design.

Similarly, Clinton allowed for the growth of huge financial firms that relied on the government for implicit too big to fail insurance. This free government insurance was a massive subsidy to the top executives and shareholders of these institutions.

Clinton also strengthened and lengthened copyright and patent monopolies. These are forms of government intervention in the market that have the same effect on the price of drugs and other protected items as a tariff of several thousand percent. In the case of drugs the costs are not only economic, but also felt in the form of bad health outcomes from mismarketed drugs by companies trying to maximize their patent rents.

And, the federal government directly intervenes to redistribute income upward when the Federal Reserve Board raises interest rates to slow job creation, keeping workers at the middle and bottom of the income distribution from getting enough bargaining power to raise their wages.

In these areas and others, David Brooks center-right politicians, as well as “opportunity” progressives are every bit as willing to use the government to intervene in the market as people like Warren and de Blasio. The difference is that the politicians Brooks admires want to use the government to redistribute income upward, while Warren and de Blasio want to ensure that people at the middle and bottom get their share of the gains from economic growth.

Their agenda is laid out in more detail in this report from the Roosevelt Institute.

Addendum:

I should also add that David Brooks’ “opportunity progressives,” Tony Blair and Bill Clinton, laid the groundwork for massive housing bubbles whose collapse sank their respective economies. It would be hard to be imagine a more disastrous economic policy, although in Clinton’s case the worst could have been avoided if his successor was awake.

David Brooks used the victory of the Conservatives in the United Kingdom to celebrate the “center-right moment” in his column this morning. To make his case he largely creates a caricature of the left to argue for the greater wisdom of the center-right. He tells readers:

“Over the past few years, left-of-center economic policy has moved from opportunity progressivism to redistributionist progressivism. Opportunity progressivism is associated with Bill Clinton and Tony Blair in the 1990s and Mayor Rahm Emanuel of Chicago today. This tendency actively uses government power to give people access to markets, through support for community colleges, infrastructure and training programs and the like, but it doesn’t interfere that much in the market and hesitates before raising taxes.

“This tendency has been politically successful. Clinton and Blair had long terms. This year, Emanuel won by 12 percentage points against the more progressive candidate, Chuy Garcia, even in a city with a disproportionate number of union households.

“Redistributionist progressivism more aggressively raises taxes to shift money down the income scale, opposes trade treaties and meddles more in the marketplace. This tendency has won elections in Massachusetts (Elizabeth Warren) and New York City (Bill de Blasio) but not in many other places.”

For political purposes it is undoubtedly advantageous to imply that the “opportunity” progressives favored the market more than the “redistributionist progressives,” but it is not true. Taking the case of President Clinton, he promoted trade agreements that deliberately placed manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world, while maintaining or increasing the protections for highly paid professionals like doctors and lawyers. This had the predicted and actual effect of raising the incomes of those at the top at the expense of those at the middle and bottom. This upward redistribution was not due to market forces, but to policy design.

Similarly, Clinton allowed for the growth of huge financial firms that relied on the government for implicit too big to fail insurance. This free government insurance was a massive subsidy to the top executives and shareholders of these institutions.

Clinton also strengthened and lengthened copyright and patent monopolies. These are forms of government intervention in the market that have the same effect on the price of drugs and other protected items as a tariff of several thousand percent. In the case of drugs the costs are not only economic, but also felt in the form of bad health outcomes from mismarketed drugs by companies trying to maximize their patent rents.

And, the federal government directly intervenes to redistribute income upward when the Federal Reserve Board raises interest rates to slow job creation, keeping workers at the middle and bottom of the income distribution from getting enough bargaining power to raise their wages.

In these areas and others, David Brooks center-right politicians, as well as “opportunity” progressives are every bit as willing to use the government to intervene in the market as people like Warren and de Blasio. The difference is that the politicians Brooks admires want to use the government to redistribute income upward, while Warren and de Blasio want to ensure that people at the middle and bottom get their share of the gains from economic growth.

Their agenda is laid out in more detail in this report from the Roosevelt Institute.

Addendum:

I should also add that David Brooks’ “opportunity progressives,” Tony Blair and Bill Clinton, laid the groundwork for massive housing bubbles whose collapse sank their respective economies. It would be hard to be imagine a more disastrous economic policy, although in Clinton’s case the worst could have been avoided if his successor was awake.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson apparently doesn’t understand much about the economy and economics. That’s fine, many people don’t. Unfortunately, Mr. Samuelson has an economics column in a major national newspaper and he wants to attribute his ignorance to the rest of us.

In his column today bemoaning the seeming end of a trade-off between inequality and efficiency (we could buy ourselves some more equality at the price of a loss of efficiency) he tells readers:

“We do not know enough to manipulate economic growth, productivity and income distribution. …

“Okun’s book is emblematic of an era of overconfident economics. The underlying questions remain. Is the convergence of rising inequality and falling economic growth simply a coincidence? Or is more inequality a cause of weaker growth, a consequence of it — perhaps both? We lack definitive answers. Government must routinely act without full knowledge. That’s the point: In the real world, we often don’t know the true tradeoffs.”

Actually “we” know pretty well what happened. Since the rise in the dollar in the late 1990s, the U.S. has had a large trade deficit, which creates a big gap in demand. This gap in demand was filled by a stock bubble at the end of the 1990s and a housing bubble in the last decade. When the housing bubble burst, there was nothing to fill the demand gap created by the trade deficit.

Since it is not politically acceptable to talk about large budget deficits, and there is little interest in work sharing and other policies to reduce supply, the economy is likely to remain well below full employment levels of output. When the economy is below full employment, workers lack the bargaining power to secure their share of productivity growth, leading to upward redistribution. Upward redistribution is also helped by stronger and longer patent and copyright protection, special tax breaks that cultivate niches for finance, and subsidies to top management at non-profits (e.g. universities, hospitals, and foundations) in the form of tax exempt status.

We could reverse the situation by either having the government spend more money, pushing legislation that will tighten the labor market by reducing average hours worked per worker, or by measures that will reduce the value of the dollar against other currencies, thereby reducing the trade deficit. All of these measures would boost growth and led to stronger wage growth, thereby lessening inequality.

There is very little mystery about any of this, even if Robert Samuelson finds the situation confusing.

Robert Samuelson apparently doesn’t understand much about the economy and economics. That’s fine, many people don’t. Unfortunately, Mr. Samuelson has an economics column in a major national newspaper and he wants to attribute his ignorance to the rest of us.

In his column today bemoaning the seeming end of a trade-off between inequality and efficiency (we could buy ourselves some more equality at the price of a loss of efficiency) he tells readers:

“We do not know enough to manipulate economic growth, productivity and income distribution. …

“Okun’s book is emblematic of an era of overconfident economics. The underlying questions remain. Is the convergence of rising inequality and falling economic growth simply a coincidence? Or is more inequality a cause of weaker growth, a consequence of it — perhaps both? We lack definitive answers. Government must routinely act without full knowledge. That’s the point: In the real world, we often don’t know the true tradeoffs.”

Actually “we” know pretty well what happened. Since the rise in the dollar in the late 1990s, the U.S. has had a large trade deficit, which creates a big gap in demand. This gap in demand was filled by a stock bubble at the end of the 1990s and a housing bubble in the last decade. When the housing bubble burst, there was nothing to fill the demand gap created by the trade deficit.

Since it is not politically acceptable to talk about large budget deficits, and there is little interest in work sharing and other policies to reduce supply, the economy is likely to remain well below full employment levels of output. When the economy is below full employment, workers lack the bargaining power to secure their share of productivity growth, leading to upward redistribution. Upward redistribution is also helped by stronger and longer patent and copyright protection, special tax breaks that cultivate niches for finance, and subsidies to top management at non-profits (e.g. universities, hospitals, and foundations) in the form of tax exempt status.

We could reverse the situation by either having the government spend more money, pushing legislation that will tighten the labor market by reducing average hours worked per worker, or by measures that will reduce the value of the dollar against other currencies, thereby reducing the trade deficit. All of these measures would boost growth and led to stronger wage growth, thereby lessening inequality.

There is very little mystery about any of this, even if Robert Samuelson finds the situation confusing.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

You have to admire Niall Ferguson. There aren’t many people who are willing to write lengthy diatribes on topics on which they seem to know next to nothing, but some would say that is the definition of a Harvard professor.

Anyhow, he apparently believes that the victory of the Conservative Party in the U.K. election last week showed that he was correct to endorse their austerity policy and that Paul Krugman was wrong to criticize it. If he was familiar at all with the literature on the impact of the economy on elections he would know that elections are largely determined by the economy’s performance in the last year before an election, not an administration’s entire term. And, since the conservatives relaxed their austerity in the last two years (as had been widely noted long before the election), the economy was not performing badly in the immediate lead up to the election.

Ferguson’s piece presents a cornucopia of silly mistakes, which I don’t have time to address, but I will give my favorite:

“On more than one occasion during the crisis, Krugman applauded Gordon Brown for injecting capital directly into the British banks rather than relying on purchases of “troubled assets,” the initial thrust of the Troubled Asset Relief Program in the United States. In October 2008, Krugman engaged in the kind of sycophancy that usually indicates a man angling for a knighthood:

‘Has Gordon Brown, the British prime minister, saved the world financial system? … The Brown government has shown itself willing to think clearly about the financial crisis, and act quickly on its conclusions. …. Governments [should] provide financial institutions with more capital in return for a share of ownership … [a] sort of temporary part-nationalization … The British government went straight to the heart of the problem – and moved to address it with stunning speed.’

“TARP has of course proved far more successful than the UK’s nationalization of too-big-to-fail behemoths like RBS.”

The small detail that Ferguson apparently missed is that TARP also went the route of giving the banks capital in exchange for share ownership in the form of the purchase of shares of preferred stock. At the time, Plan A from the Bush administration was to directly purchase the bad assets from the banks (hence the name “Troubled Asset Relief Program”). Krugman and others argued that the better route was to give the banks capital, which is what TARP eventually did, following Gordon Brown’s lead. (I personally favored letting the market work its magic and then pick up the pieces after the Wall Street behemoths were buried in the ground.) In other words, Ferguson is bizarrely holding up TARP as an alternative course to the path set out by Brown, when in fact it followed the path set out by Brown.

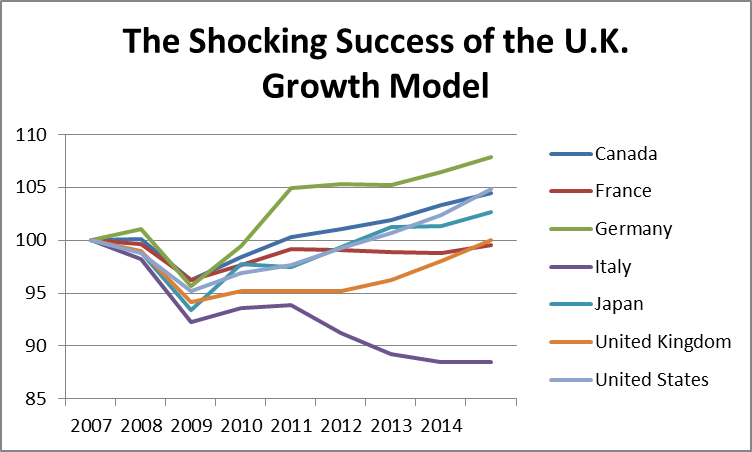

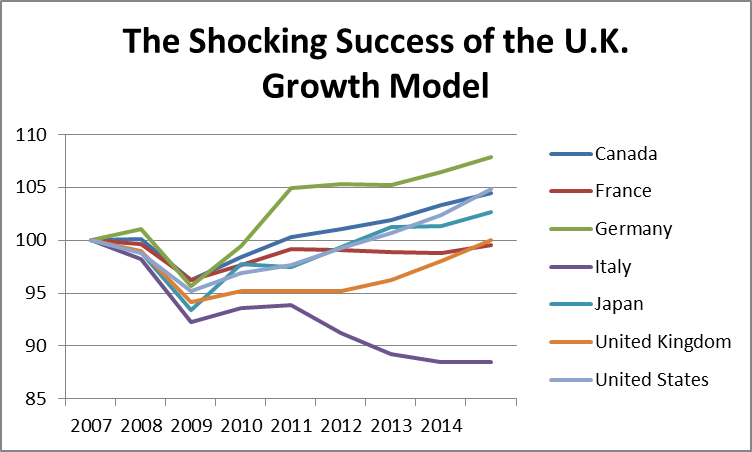

But the real story is the overall performance of the U.K. economy, which Ferguson somehow thinks was extraordinary. The data beg to differ, even if the U.K. has done better in the last couple of years as the government relaxed its austerity. Here is the per capita GDP record of the G-7 economies since the crisis.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

As can be seen, the U.K. ties France for fifth place, only beating out Italy for last place. If we treat 2010 as the start point, it managed to close the gap with France in the next four years (which also was forced to pursue austerity since it was in the euro zone), but fell further behind Germany, Japan, Canada, and the U.S.

In 2014, seven years after the beginning of the crisis, per capita GDP in the U.K. was virtually identical to what it had been in 2007. By comparison, per capita GDP in the U.S. in 1988 was 20.1 percent higher than it had been at start of the 1981 recession. In 1997 it was 12.8 percent larger than it had been at the start of the recession in 1990. It would require some extraordinary affirmative action for conservative politicians to follow Ferguson and declare the Cameron record a success.

Addendum

For folks who thought I was being unfair to use 2010 as a reference point, since Cameron only took office mid-year, you’re right. The OECD has the quarterly data. The UK economy grew at a 2.0 percent annual rate in the first quarter and a 4.0 percent rate in the second quarter when Cameron took office. This slowed to 2.6 percent in the third quarter and 0.1 percent in the fourth quarter. So taking the year as a whole as the start point for Cameron is undoubtedly too generous.

I should also explain that there is a reason for using the pre-recession level of output as a reference point. In the old days (i.e. before the pathetic recovery from this downturn) economists expected economies to bounce back quickly from a recession, making up the ground lost in the recession. This is why we had years of 5-7 percent growth following the steep downturns in 1974-1975 and 1981-1982. This recession has been different in that we have not seen a steep bounce back in any country. I feel it is appropriate to apply normal economic standards to evaluate policy performance instead of using affirmative action for inept policymakers.

You have to admire Niall Ferguson. There aren’t many people who are willing to write lengthy diatribes on topics on which they seem to know next to nothing, but some would say that is the definition of a Harvard professor.

Anyhow, he apparently believes that the victory of the Conservative Party in the U.K. election last week showed that he was correct to endorse their austerity policy and that Paul Krugman was wrong to criticize it. If he was familiar at all with the literature on the impact of the economy on elections he would know that elections are largely determined by the economy’s performance in the last year before an election, not an administration’s entire term. And, since the conservatives relaxed their austerity in the last two years (as had been widely noted long before the election), the economy was not performing badly in the immediate lead up to the election.

Ferguson’s piece presents a cornucopia of silly mistakes, which I don’t have time to address, but I will give my favorite:

“On more than one occasion during the crisis, Krugman applauded Gordon Brown for injecting capital directly into the British banks rather than relying on purchases of “troubled assets,” the initial thrust of the Troubled Asset Relief Program in the United States. In October 2008, Krugman engaged in the kind of sycophancy that usually indicates a man angling for a knighthood:

‘Has Gordon Brown, the British prime minister, saved the world financial system? … The Brown government has shown itself willing to think clearly about the financial crisis, and act quickly on its conclusions. …. Governments [should] provide financial institutions with more capital in return for a share of ownership … [a] sort of temporary part-nationalization … The British government went straight to the heart of the problem – and moved to address it with stunning speed.’

“TARP has of course proved far more successful than the UK’s nationalization of too-big-to-fail behemoths like RBS.”

The small detail that Ferguson apparently missed is that TARP also went the route of giving the banks capital in exchange for share ownership in the form of the purchase of shares of preferred stock. At the time, Plan A from the Bush administration was to directly purchase the bad assets from the banks (hence the name “Troubled Asset Relief Program”). Krugman and others argued that the better route was to give the banks capital, which is what TARP eventually did, following Gordon Brown’s lead. (I personally favored letting the market work its magic and then pick up the pieces after the Wall Street behemoths were buried in the ground.) In other words, Ferguson is bizarrely holding up TARP as an alternative course to the path set out by Brown, when in fact it followed the path set out by Brown.

But the real story is the overall performance of the U.K. economy, which Ferguson somehow thinks was extraordinary. The data beg to differ, even if the U.K. has done better in the last couple of years as the government relaxed its austerity. Here is the per capita GDP record of the G-7 economies since the crisis.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

As can be seen, the U.K. ties France for fifth place, only beating out Italy for last place. If we treat 2010 as the start point, it managed to close the gap with France in the next four years (which also was forced to pursue austerity since it was in the euro zone), but fell further behind Germany, Japan, Canada, and the U.S.

In 2014, seven years after the beginning of the crisis, per capita GDP in the U.K. was virtually identical to what it had been in 2007. By comparison, per capita GDP in the U.S. in 1988 was 20.1 percent higher than it had been at start of the 1981 recession. In 1997 it was 12.8 percent larger than it had been at the start of the recession in 1990. It would require some extraordinary affirmative action for conservative politicians to follow Ferguson and declare the Cameron record a success.

Addendum

For folks who thought I was being unfair to use 2010 as a reference point, since Cameron only took office mid-year, you’re right. The OECD has the quarterly data. The UK economy grew at a 2.0 percent annual rate in the first quarter and a 4.0 percent rate in the second quarter when Cameron took office. This slowed to 2.6 percent in the third quarter and 0.1 percent in the fourth quarter. So taking the year as a whole as the start point for Cameron is undoubtedly too generous.

I should also explain that there is a reason for using the pre-recession level of output as a reference point. In the old days (i.e. before the pathetic recovery from this downturn) economists expected economies to bounce back quickly from a recession, making up the ground lost in the recession. This is why we had years of 5-7 percent growth following the steep downturns in 1974-1975 and 1981-1982. This recession has been different in that we have not seen a steep bounce back in any country. I feel it is appropriate to apply normal economic standards to evaluate policy performance instead of using affirmative action for inept policymakers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In an interview with Matt Bai, a political columnist with Yahoo, President Obama took issue with Senator Elizabeth Warren’s claim that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and other trade deals that could be allowed special rules under fast-track status, could unravel financial regulation put in place by Dodd-Frank.

“‘Think about the logic of that, right?’ he went on. ‘The notion that I had this massive fight with Wall Street to make sure that we don’t repeat what happened in 2007, 2008. And then I sign a provision that would unravel it?’

“’I’d have to be pretty stupid,’ Obama said, laughing.”

President Obama may not want to rest the case for TPP on the strength of his status as a foe of Wall Street. He has not always been the strongest proponent of financial reform. Among other noteworthy items:

1) He has not sought the criminal prosecution of any executives at major banks for issuing or securitizing fraudulent mortgages, nor against executives at credit rating agencies for knowingly granting investment grade ratings to securities containing large numbers of improper or fraudulent mortgages;

2) He opposed the Brown-Kauffman bill, which would have broken up the big banks;

3) He did nothing to push cram-down legislation in Congress, which would have required banks to write-down the value of some underwater mortgages to the current market value of the home;

4) He supported the stripping of the Franken Amendment from Dodd-Frank. This amendment (which was approved by a large bi-partisan majority in the Senate) would have eliminated the conflict of interest faced by bond-rating agencies by having the Securities and Exchange Commission, rather than the issuer, pick the rating agency. (The line from opponents was that the SEC might send over unqualified analysts. Think about that one for a while.)

5) He only began to push the Volcker rule as a political move to shore up support the day after Republican Scott Brown won an upset election for a Senate seat in Massachusetts.

6) The administration had to be pushed by labor and consumer groups to keep a strong and independent consumer financial protection bureau in Dodd-Frank.

If President Obama wants to push the case for TPP he should probably rely on something other than his status as a foe of Wall Street.

Addendum:

It is worth noting that the fast-track legislation being requested by President Obama would extend for five years. This means that if a Republican is elected in 2016, they would be able to have future trade agreements approved on a straight up or down vote by a majority in Congress. If it is difficult to see how President Obama can assure Senator Warren, and other critics of fast-track, that a future Republican president would not use this power to weaken financial regulation, if they could not otherwise get the 60 votes needed in the Senate to overcome a filibuster.

In an interview with Matt Bai, a political columnist with Yahoo, President Obama took issue with Senator Elizabeth Warren’s claim that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and other trade deals that could be allowed special rules under fast-track status, could unravel financial regulation put in place by Dodd-Frank.

“‘Think about the logic of that, right?’ he went on. ‘The notion that I had this massive fight with Wall Street to make sure that we don’t repeat what happened in 2007, 2008. And then I sign a provision that would unravel it?’

“’I’d have to be pretty stupid,’ Obama said, laughing.”

President Obama may not want to rest the case for TPP on the strength of his status as a foe of Wall Street. He has not always been the strongest proponent of financial reform. Among other noteworthy items:

1) He has not sought the criminal prosecution of any executives at major banks for issuing or securitizing fraudulent mortgages, nor against executives at credit rating agencies for knowingly granting investment grade ratings to securities containing large numbers of improper or fraudulent mortgages;

2) He opposed the Brown-Kauffman bill, which would have broken up the big banks;

3) He did nothing to push cram-down legislation in Congress, which would have required banks to write-down the value of some underwater mortgages to the current market value of the home;

4) He supported the stripping of the Franken Amendment from Dodd-Frank. This amendment (which was approved by a large bi-partisan majority in the Senate) would have eliminated the conflict of interest faced by bond-rating agencies by having the Securities and Exchange Commission, rather than the issuer, pick the rating agency. (The line from opponents was that the SEC might send over unqualified analysts. Think about that one for a while.)

5) He only began to push the Volcker rule as a political move to shore up support the day after Republican Scott Brown won an upset election for a Senate seat in Massachusetts.

6) The administration had to be pushed by labor and consumer groups to keep a strong and independent consumer financial protection bureau in Dodd-Frank.

If President Obama wants to push the case for TPP he should probably rely on something other than his status as a foe of Wall Street.

Addendum:

It is worth noting that the fast-track legislation being requested by President Obama would extend for five years. This means that if a Republican is elected in 2016, they would be able to have future trade agreements approved on a straight up or down vote by a majority in Congress. If it is difficult to see how President Obama can assure Senator Warren, and other critics of fast-track, that a future Republican president would not use this power to weaken financial regulation, if they could not otherwise get the 60 votes needed in the Senate to overcome a filibuster.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión