It’s getting harder and harder to figure out what the Washington Post wants us to be worried about as the budget standoff approaches some sort of resolution. A front page Post article today warned readers that some tax increases and spending cuts are still likely to take effect on January 1, even if there is an agreement to extend the Bush tax cuts for the bottom 98 percent of households and to fix the alternative minimum tax and some other expiring provisions. The Post accurately points out that these residual tax increases and spending cuts will have the effect of slowing the economy.

However, the residual tax increases and spending cuts can also be called “deficit reduction” of the sort that the Post has been demanding to combat the deficits that have been causing it to hyperventilate for years. It was possible to point to many of the tax increases and spending cuts that were associated with the “cliff” as accidents that no one actually wanted to see go into effect, but the residual tax increases and spending cuts are likely to be there in large part by design.

While this will be bad news for an economy that desperately needs more stimulus (i.e. larger deficits), and also for the people directly affected, this is exactly the policy that the Post and other Washington establishment figures from both parties have been demanding. It would have been worth pointing out that the resulting hit to the economy is exactly what most advocates of deficit reduction presumably want if they understand the impact of the policies they advocate.

At one point this article tells readers:

“Hovering over these negotiations are reminders of the summer of 2011, when Obama and Boehner tried in vain to craft a “grand bargain” that would have saved $4 trillion in spending over the next decade and allowed an increase in the federal debt limit.”

This is not true. Obama and Boehner were never close to a deal that involved $4 trillion in spending cuts. They had set this $4 trillion figure as a target for deficit reduction, which would include spending cuts, tax increases and interest savings.

It’s getting harder and harder to figure out what the Washington Post wants us to be worried about as the budget standoff approaches some sort of resolution. A front page Post article today warned readers that some tax increases and spending cuts are still likely to take effect on January 1, even if there is an agreement to extend the Bush tax cuts for the bottom 98 percent of households and to fix the alternative minimum tax and some other expiring provisions. The Post accurately points out that these residual tax increases and spending cuts will have the effect of slowing the economy.

However, the residual tax increases and spending cuts can also be called “deficit reduction” of the sort that the Post has been demanding to combat the deficits that have been causing it to hyperventilate for years. It was possible to point to many of the tax increases and spending cuts that were associated with the “cliff” as accidents that no one actually wanted to see go into effect, but the residual tax increases and spending cuts are likely to be there in large part by design.

While this will be bad news for an economy that desperately needs more stimulus (i.e. larger deficits), and also for the people directly affected, this is exactly the policy that the Post and other Washington establishment figures from both parties have been demanding. It would have been worth pointing out that the resulting hit to the economy is exactly what most advocates of deficit reduction presumably want if they understand the impact of the policies they advocate.

At one point this article tells readers:

“Hovering over these negotiations are reminders of the summer of 2011, when Obama and Boehner tried in vain to craft a “grand bargain” that would have saved $4 trillion in spending over the next decade and allowed an increase in the federal debt limit.”

This is not true. Obama and Boehner were never close to a deal that involved $4 trillion in spending cuts. They had set this $4 trillion figure as a target for deficit reduction, which would include spending cuts, tax increases and interest savings.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post has been an unofficial partner in the corporate sponsored Campaign to Fix the Debt’s efforts to cut Social Security and Medicare, devoting much of its news and opinion sections to advancing its agenda. This political position explains an article that examined the prospects for the U.S. economy after the budget impasse (a.k.a. the “fiscal cliff”) is resolved. The piece relied extensively on assertions from David M. Cote, a prominent deficit hawk and the CEO of Honeywell.

The piece quotes Cote:

“There is the possibility of a robust economic recovery if we are smart here. .?.?. If all of a sudden we can demonstrate that we can govern ourselves, we could affect the world.”

In this context it probably would have been worth mentioning that the interest rate on long-term Treasury bonds is just 1.7 percent. This fact suggests that most actors in financial markets do not share Mr. Cote’s concern about the ability of the United States to govern itself.

The piece relies further on Cote:

“He said the United States needs a tax-and-spending package of at least $4 trillion to be judged ‘credible’ by investors and trigger renewed growth. As head of Honeywell, he has frozen most hiring and capital investment because of uncertainty about the fiscal cliff — a strategy other corporate heads have followed as well to hedge against a new downturn.”

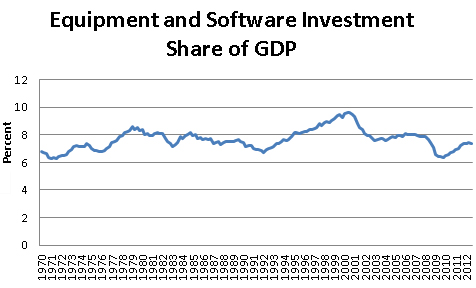

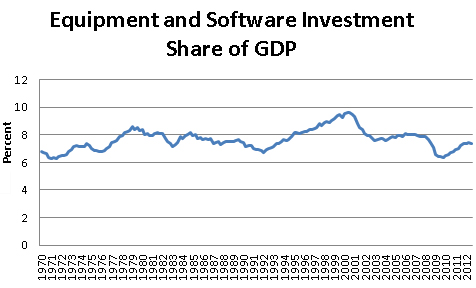

There is an easy way to evaluate this assertion. If what Cote is saying is true then we should be seeing unusually low levels of investment right now. In fact data from the Commerce Department show that, as a share of GDP, investment in equipment and software is only slightly below its pre-recession level. This is especially impressive given that large sectors of the economy are still operating well below their capacity.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

It is true that there has been some weakening of investment growth in the last half year or so, but even if investment returned to its growth rate in the first half of the year it would only have a modest impact on the pace of the recovery. In short, the data from the Commerce Department do not support what Mr. Cote is saying. If he in fact is delaying Honeywell investment because of uncertainty about the fiscal situation he is an exception among corporate decision makers.

This article also includes a bizarre comment in its discussion of the more rapid growth in the developing world in recent years, telling readers:

“But that could also sow the seeds of the next crisis if money floods into nations that are not equipped to manage it.”

The statement is of course true, but it is not clear what countries have demonstrated an ability to manage large inflows of money. Clearly the United States does not fit the bill.

Addendum:

A quick trip to Honeywell’s website indicates that the company does not appear to be putting its expansion plans on hold as Mr. Cote claimed. In the last two weeks it announced $20 million in new contracts to produce simulations for industrial companies, a new contract with Boeing, and the purchase of another company for $600 million.

The Washington Post has been an unofficial partner in the corporate sponsored Campaign to Fix the Debt’s efforts to cut Social Security and Medicare, devoting much of its news and opinion sections to advancing its agenda. This political position explains an article that examined the prospects for the U.S. economy after the budget impasse (a.k.a. the “fiscal cliff”) is resolved. The piece relied extensively on assertions from David M. Cote, a prominent deficit hawk and the CEO of Honeywell.

The piece quotes Cote:

“There is the possibility of a robust economic recovery if we are smart here. .?.?. If all of a sudden we can demonstrate that we can govern ourselves, we could affect the world.”

In this context it probably would have been worth mentioning that the interest rate on long-term Treasury bonds is just 1.7 percent. This fact suggests that most actors in financial markets do not share Mr. Cote’s concern about the ability of the United States to govern itself.

The piece relies further on Cote:

“He said the United States needs a tax-and-spending package of at least $4 trillion to be judged ‘credible’ by investors and trigger renewed growth. As head of Honeywell, he has frozen most hiring and capital investment because of uncertainty about the fiscal cliff — a strategy other corporate heads have followed as well to hedge against a new downturn.”

There is an easy way to evaluate this assertion. If what Cote is saying is true then we should be seeing unusually low levels of investment right now. In fact data from the Commerce Department show that, as a share of GDP, investment in equipment and software is only slightly below its pre-recession level. This is especially impressive given that large sectors of the economy are still operating well below their capacity.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

It is true that there has been some weakening of investment growth in the last half year or so, but even if investment returned to its growth rate in the first half of the year it would only have a modest impact on the pace of the recovery. In short, the data from the Commerce Department do not support what Mr. Cote is saying. If he in fact is delaying Honeywell investment because of uncertainty about the fiscal situation he is an exception among corporate decision makers.

This article also includes a bizarre comment in its discussion of the more rapid growth in the developing world in recent years, telling readers:

“But that could also sow the seeds of the next crisis if money floods into nations that are not equipped to manage it.”

The statement is of course true, but it is not clear what countries have demonstrated an ability to manage large inflows of money. Clearly the United States does not fit the bill.

Addendum:

A quick trip to Honeywell’s website indicates that the company does not appear to be putting its expansion plans on hold as Mr. Cote claimed. In the last two weeks it announced $20 million in new contracts to produce simulations for industrial companies, a new contract with Boeing, and the purchase of another company for $600 million.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post again misled readers in an article on the budget standoff, which it calls the “fiscal cliff” to exaggerate the urgency of reaching a deal before the end of the year. It reported on a possible deal which it said:

“Senior Senate Republicans, meanwhile, were at work on a fallback plan that would not significantly restrain the national debt but would at least avert widespread economic damage by canceling tax increases scheduled to take effect next year for the vast majority of Americans. That strategy calls for Republicans to capitulate to Obama’s demand to let tax rates rise on wage and salary income for the wealthiest 2 percent of taxpayers.

“But the approach would also seek to thwart the Democrats by trying to block other steps that would increase taxes paid by wealthy taxpayers, including higher rates on investment income and limits on the value of itemized deductions.”

While the piece does not spell out “other steps that would increase taxes paid by wealthy taxpayers,” the list presumably includes the rise in the capital gains tax rate and the ending of the preferential tax treatment of dividend income. Referring to these as “steps” implies that action must be taken for these tax increases to go into effect. This is not true.

If nothing is done, these tax increases will go into effect on January 1, 2013. This distinction is important because the Post’s discussion might lead readers to underestimate the strength of President Obama’s position. Since the article does not provide much actual information, as opposed to speculation, it should at least be able to convey what measures involve action by Congress as opposed to doing nothing. In this case it is suggesting that President Obama would agree to sign on to a deal that would require he approve a substantially smaller tax increase on the wealthy than is specified in current law. This fact should have been made clear to readers.

The piece then continues:

“This strategy would produce only about $440 billion in new taxes and give the Democrats even less revenue than Republicans had previously put on the table. In his initial offer earlier this month, Boehner had said he could support $800 billion in new tax revenue.

“With a relatively low price in new taxes, the strategy, if successful, would represent a tactical victory for Republicans and shift the political burden onto Democrats to make greater concessions on federal spending.”

It would be useful if the piece informed readers how it determined that smaller tax increases on the rich would: “shift the political burden onto Democrats to make greater concessions on federal spending.”

Those of us less familiar with the workings of Washington might think that smaller sacrifices by the rich would be accompanied by smaller sacrifices by the non-rich. Somehow the Post has determined the opposite is the case, if there will be political pressure for everyone else to accept big cuts in programs like Social Security and Medicare. It would be great if the Post could explain to readers how this works. It is unlikely that many voters think that because the rich refuse to pay more taxes that ordinary workers should agree to accept cuts in their Social Security and Medicare.

The Post again misled readers in an article on the budget standoff, which it calls the “fiscal cliff” to exaggerate the urgency of reaching a deal before the end of the year. It reported on a possible deal which it said:

“Senior Senate Republicans, meanwhile, were at work on a fallback plan that would not significantly restrain the national debt but would at least avert widespread economic damage by canceling tax increases scheduled to take effect next year for the vast majority of Americans. That strategy calls for Republicans to capitulate to Obama’s demand to let tax rates rise on wage and salary income for the wealthiest 2 percent of taxpayers.

“But the approach would also seek to thwart the Democrats by trying to block other steps that would increase taxes paid by wealthy taxpayers, including higher rates on investment income and limits on the value of itemized deductions.”

While the piece does not spell out “other steps that would increase taxes paid by wealthy taxpayers,” the list presumably includes the rise in the capital gains tax rate and the ending of the preferential tax treatment of dividend income. Referring to these as “steps” implies that action must be taken for these tax increases to go into effect. This is not true.

If nothing is done, these tax increases will go into effect on January 1, 2013. This distinction is important because the Post’s discussion might lead readers to underestimate the strength of President Obama’s position. Since the article does not provide much actual information, as opposed to speculation, it should at least be able to convey what measures involve action by Congress as opposed to doing nothing. In this case it is suggesting that President Obama would agree to sign on to a deal that would require he approve a substantially smaller tax increase on the wealthy than is specified in current law. This fact should have been made clear to readers.

The piece then continues:

“This strategy would produce only about $440 billion in new taxes and give the Democrats even less revenue than Republicans had previously put on the table. In his initial offer earlier this month, Boehner had said he could support $800 billion in new tax revenue.

“With a relatively low price in new taxes, the strategy, if successful, would represent a tactical victory for Republicans and shift the political burden onto Democrats to make greater concessions on federal spending.”

It would be useful if the piece informed readers how it determined that smaller tax increases on the rich would: “shift the political burden onto Democrats to make greater concessions on federal spending.”

Those of us less familiar with the workings of Washington might think that smaller sacrifices by the rich would be accompanied by smaller sacrifices by the non-rich. Somehow the Post has determined the opposite is the case, if there will be political pressure for everyone else to accept big cuts in programs like Social Security and Medicare. It would be great if the Post could explain to readers how this works. It is unlikely that many voters think that because the rich refuse to pay more taxes that ordinary workers should agree to accept cuts in their Social Security and Medicare.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post is getting very upset that people refuse to accept its assertion that Social Security contributes to the deficit. An editorial today angrily referred to the “mythology that, though the pension and disability program is facing ever-widening shortfalls, it isn’t contributing to the overall deficit.”

It’s not clear why the Post thinks of the law (even as acknowledged by Republican Social Security trustee Charles Blahous) that Social Security can only spend its designated revenue and no more, as “mythology.” Social Security was set up by Congress as a stand alone program. Every official budget document includes the “on-budget” deficit, which excludes the revenue and spending of Social Security.

This would be comparable to setting up a public auto insurance system that collected insurance premiums and paid out claims, but was not allowed to tap federal revenue if it faced a shortfall. Presumably the Post would be able to understand that this auto insurance system was not contributing to the budget deficit, since the law makes it impossible to contrbute to the deficit. But somehow the Post wants to deride the law governing Social Security’s finances as “mythology.”

The editorial also includes the usual misleading comment that:

“The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates that, without reform, spending on Social Security and federal health-care programs will rise from 10 percent of gross domestic product today to 16 percent 25 years from now.”

The vast majority of this increase is due to health care costs. Social Security is projected to increase by 1.0 percentage point of GDP over the next 25 years. Almost all of this is projected to be covered by Social Security’s designated revenue stream as Social Security is projected to be able to make all payments through the year 2034 with no changes whatsoever and after that date is projected by CBO to be able to pay almost 80 percent of scheduled benefits.

The vast majority of the rise in projected spending is due to the fact that U.S. per person health care costs are projected to rise from more than twice the average in other wealthy countries to three or four times the spending of other wealthy countries. This is why serious people focus on restraining costs in the private health care system. If U.S. costs were anywhere near comparable to costs in other countries we would be looking at large budget surpluses in the distant future, not deficits.

The Washington Post is getting very upset that people refuse to accept its assertion that Social Security contributes to the deficit. An editorial today angrily referred to the “mythology that, though the pension and disability program is facing ever-widening shortfalls, it isn’t contributing to the overall deficit.”

It’s not clear why the Post thinks of the law (even as acknowledged by Republican Social Security trustee Charles Blahous) that Social Security can only spend its designated revenue and no more, as “mythology.” Social Security was set up by Congress as a stand alone program. Every official budget document includes the “on-budget” deficit, which excludes the revenue and spending of Social Security.

This would be comparable to setting up a public auto insurance system that collected insurance premiums and paid out claims, but was not allowed to tap federal revenue if it faced a shortfall. Presumably the Post would be able to understand that this auto insurance system was not contributing to the budget deficit, since the law makes it impossible to contrbute to the deficit. But somehow the Post wants to deride the law governing Social Security’s finances as “mythology.”

The editorial also includes the usual misleading comment that:

“The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates that, without reform, spending on Social Security and federal health-care programs will rise from 10 percent of gross domestic product today to 16 percent 25 years from now.”

The vast majority of this increase is due to health care costs. Social Security is projected to increase by 1.0 percentage point of GDP over the next 25 years. Almost all of this is projected to be covered by Social Security’s designated revenue stream as Social Security is projected to be able to make all payments through the year 2034 with no changes whatsoever and after that date is projected by CBO to be able to pay almost 80 percent of scheduled benefits.

The vast majority of the rise in projected spending is due to the fact that U.S. per person health care costs are projected to rise from more than twice the average in other wealthy countries to three or four times the spending of other wealthy countries. This is why serious people focus on restraining costs in the private health care system. If U.S. costs were anywhere near comparable to costs in other countries we would be looking at large budget surpluses in the distant future, not deficits.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Much of the media has spent the last month and a half hyping the impact of the “fiscal cliff,” the tax increases and spending cuts that are scheduled to take effect at the end of the year. They have been warning of a recession and other dire consequences if a deal is not struck by December 31st. As we are now getting down to the final two weeks and the prospect that there will not be a deal becomes more likely, many in the media are getting more frantic.

What they fear is yet another huge embarrassment, if people see the deadline come and go and the economy doesn’t crash and the world doesn’t end. The reality, as all budget analysts know, is that no one will see more taxes coming out of their paychecks until they actually get paid later in the month. If a deal is imminent or actually struck in the first weeks of January then most workers will never be taxed at the higher Clinton era rate. They will be taxed in accordance with the deal that President Obama reaches with the Republicans.

And those who do have money taken out of a check will have it returned in the next one. This might be bad news for people who are skimming by paycheck to paycheck, but the impact on the economy will be too small to measure.

The same applies on the spending side. If President Obama sees a deal in sight then he will adjust spending in accordance with the amount that he expects to agree to with Congress, not the amount specified in the sequester. The impact on the economy will be essentially zero, except of course for the impact of the budget cuts that Congress and President Obama actually agree to put in place.

In other words, if January 1, 2013 comes and there is no deal, we will likely see that the Serious People were again out to lunch. This will be yet another blow to the credibility of the people who are telling us that we have to cut Social Security and Medicare and do all sorts of other things that somehow always seem to have the effect of hurting the poor and middle class.

Of course many may say that the Serious People have recovered from past humiliations. After all, how long did it take them to get over the fact that not one of them was able to see the $8 trillion housing bubble whose collapse wrecked the economy? And there can be little doubt that they will quickly rewrite the history so that none of them was actually issuing the dire warnings we keep hearing about the fiscal cliff.

But some people will remember, and there will always be people rude enough to bring up past mistakes. So the Serious People really do have a lot at stake here. If we go past January 1 and there is no deal, they will be very unhappy.

Much of the media has spent the last month and a half hyping the impact of the “fiscal cliff,” the tax increases and spending cuts that are scheduled to take effect at the end of the year. They have been warning of a recession and other dire consequences if a deal is not struck by December 31st. As we are now getting down to the final two weeks and the prospect that there will not be a deal becomes more likely, many in the media are getting more frantic.

What they fear is yet another huge embarrassment, if people see the deadline come and go and the economy doesn’t crash and the world doesn’t end. The reality, as all budget analysts know, is that no one will see more taxes coming out of their paychecks until they actually get paid later in the month. If a deal is imminent or actually struck in the first weeks of January then most workers will never be taxed at the higher Clinton era rate. They will be taxed in accordance with the deal that President Obama reaches with the Republicans.

And those who do have money taken out of a check will have it returned in the next one. This might be bad news for people who are skimming by paycheck to paycheck, but the impact on the economy will be too small to measure.

The same applies on the spending side. If President Obama sees a deal in sight then he will adjust spending in accordance with the amount that he expects to agree to with Congress, not the amount specified in the sequester. The impact on the economy will be essentially zero, except of course for the impact of the budget cuts that Congress and President Obama actually agree to put in place.

In other words, if January 1, 2013 comes and there is no deal, we will likely see that the Serious People were again out to lunch. This will be yet another blow to the credibility of the people who are telling us that we have to cut Social Security and Medicare and do all sorts of other things that somehow always seem to have the effect of hurting the poor and middle class.

Of course many may say that the Serious People have recovered from past humiliations. After all, how long did it take them to get over the fact that not one of them was able to see the $8 trillion housing bubble whose collapse wrecked the economy? And there can be little doubt that they will quickly rewrite the history so that none of them was actually issuing the dire warnings we keep hearing about the fiscal cliff.

But some people will remember, and there will always be people rude enough to bring up past mistakes. So the Serious People really do have a lot at stake here. If we go past January 1 and there is no deal, they will be very unhappy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an article on a new study by Edward Pinto at the American Enterprise Institute which found that a high percentage of the loans the FHA insured in 2009-2010 were high risk loans that are likely to end in foreclosure. Based on its findings, the study criticized FHA lending practices. It argued that they were both leading to large losses for the program and resulting in large numbers of homes in foreclosure, which is devastating both to the homeowners and the communities in which they live.

Remarkably, the study does not take into account the impact of the first-time homebuyers tax credit. This credit had the effect of temporarily inflating house prices, especially in the bottom end of the market where FHA loans were concentrated. It was 100 percent predictable that a large percentage of these loans would end in default since house prices were certain to fall once the tax credit ended.

It is misleading to generalize from this experience that the FHA has been reckless in its lending policies. In fact, at the peak of the bubble in 2002-2006 the FHA’s market share plummeted as low and moderate income borrowers found that they could get much more lenient conditions from private lenders. While many of the points in the study are well-taken (it does not make sense to encourage people to leverage themselves heavily to buy a home where they will have great difficulty meeting the payments) the FHA does not have the history of recklessness that the piece implies.

The NYT had an article on a new study by Edward Pinto at the American Enterprise Institute which found that a high percentage of the loans the FHA insured in 2009-2010 were high risk loans that are likely to end in foreclosure. Based on its findings, the study criticized FHA lending practices. It argued that they were both leading to large losses for the program and resulting in large numbers of homes in foreclosure, which is devastating both to the homeowners and the communities in which they live.

Remarkably, the study does not take into account the impact of the first-time homebuyers tax credit. This credit had the effect of temporarily inflating house prices, especially in the bottom end of the market where FHA loans were concentrated. It was 100 percent predictable that a large percentage of these loans would end in default since house prices were certain to fall once the tax credit ended.

It is misleading to generalize from this experience that the FHA has been reckless in its lending policies. In fact, at the peak of the bubble in 2002-2006 the FHA’s market share plummeted as low and moderate income borrowers found that they could get much more lenient conditions from private lenders. While many of the points in the study are well-taken (it does not make sense to encourage people to leverage themselves heavily to buy a home where they will have great difficulty meeting the payments) the FHA does not have the history of recklessness that the piece implies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran an article noting that President Obama and many progressives seem prepared to let the Bush tax cuts remain in place for the vast majority of the population. The rationale is that most of the income gains of the last three decades have gone to those at the top of the income distribution. The piece points out that this decision could leave the government seriously short of revenue, concluding with a quote from former Obama administration economist, Jared Bernstein [a friend and co-author]:

“But ultimately we can’t raise the revenue we need only on the top 2 percent.”

Actually the seeming conundrum is not quite as bad as is portrayed here. The revenue projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and others assume that the upward redistribution of income does not continue. For example, CBO projected that the profit share of GDP would fall by almost 25 percent from 2011 to 2022 (Table 2-1). If it turns out that CBO is wrong (as it has been thus far) and the profit share of GDP continues to rise, then we will raise considerably more tax revenue from the current structure of taxes than CBO projects.

Alternatively, if CBO’s income projections prove correct, then the middle class will be seeing rapid growth in their real income. This means that they will be able to afford modest increases in their tax rates.

So the story here is not quite as dire as the article implies. As a simple rule, we can in fact raise all the revenue we need from the top 2 percent, if the top 2 percent have all the money.

The NYT ran an article noting that President Obama and many progressives seem prepared to let the Bush tax cuts remain in place for the vast majority of the population. The rationale is that most of the income gains of the last three decades have gone to those at the top of the income distribution. The piece points out that this decision could leave the government seriously short of revenue, concluding with a quote from former Obama administration economist, Jared Bernstein [a friend and co-author]:

“But ultimately we can’t raise the revenue we need only on the top 2 percent.”

Actually the seeming conundrum is not quite as bad as is portrayed here. The revenue projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and others assume that the upward redistribution of income does not continue. For example, CBO projected that the profit share of GDP would fall by almost 25 percent from 2011 to 2022 (Table 2-1). If it turns out that CBO is wrong (as it has been thus far) and the profit share of GDP continues to rise, then we will raise considerably more tax revenue from the current structure of taxes than CBO projects.

Alternatively, if CBO’s income projections prove correct, then the middle class will be seeing rapid growth in their real income. This means that they will be able to afford modest increases in their tax rates.

So the story here is not quite as dire as the article implies. As a simple rule, we can in fact raise all the revenue we need from the top 2 percent, if the top 2 percent have all the money.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post continues to ignore standard journalistic practices in its effort to push its agenda for cutting Social Security and Medicare. In an effort to maintain pressure on President Obama to reach a budget deal before the end of the year, when his bargaining power will be strengthened by the end of the Bush tax cuts, the paper inaccurately asserted:

“Economists have warned that going over the fiscal cliff — the set of sizable tax increases and spending cuts mandated to take place early next year — would throw the nation back into a recession.”

This is not true. The report that provides the basis for the linked article shows the impact on the economy of leaving the higher Clinton era tax rates in place all year, along with the budget cuts provided for in the 2011 budget agreement.

The report absolutely does not say that if the January 1 deadline is missed that the economy would go into a recession. This is an invention of the Washington Post and others who have an agenda to push.

The economic impact of having a higher tax withholding schedule in place for a week or two in 2013 would be minimal. There is no reason that spending need be changed at all if it seems that a deal between President Obama and Congress is imminent. In other words, there is no reason for people to be concerned about missing the January 1 deadline. It is unfortunate that the Post would misrepresent economic research to try to convince readers otherwise.

The Washington Post continues to ignore standard journalistic practices in its effort to push its agenda for cutting Social Security and Medicare. In an effort to maintain pressure on President Obama to reach a budget deal before the end of the year, when his bargaining power will be strengthened by the end of the Bush tax cuts, the paper inaccurately asserted:

“Economists have warned that going over the fiscal cliff — the set of sizable tax increases and spending cuts mandated to take place early next year — would throw the nation back into a recession.”

This is not true. The report that provides the basis for the linked article shows the impact on the economy of leaving the higher Clinton era tax rates in place all year, along with the budget cuts provided for in the 2011 budget agreement.

The report absolutely does not say that if the January 1 deadline is missed that the economy would go into a recession. This is an invention of the Washington Post and others who have an agenda to push.

The economic impact of having a higher tax withholding schedule in place for a week or two in 2013 would be minimal. There is no reason that spending need be changed at all if it seems that a deal between President Obama and Congress is imminent. In other words, there is no reason for people to be concerned about missing the January 1 deadline. It is unfortunate that the Post would misrepresent economic research to try to convince readers otherwise.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

At least the first $250,000 of gains is exempt for individuals and $500,000 for couples. For this reason, the Post is likely off the mark in telling readers about middle class homeowners rushing to sell their homes to take advantage of the lower capital gains tax rate.

A couple would have to have a gain of at least $500,000 for this to be an issue. That would imply a gain that is a bit less than three times the median house price nationally. That doesn’t sound like a middle class couple. Furthermore, the tax would only apply to the margin over $500,000. That means that a couple selling a home for a gain of $510,000 or $520,000 would be little affected by plausible rises in the capital gains tax rate since they would only pay the higher rate only on the amount over $500,000.

[Correction: The piece is clearly referring to investment properties. I was confused by the sentence:

“The new limit would hit the wealthy hardest, but in regions such as the Washington area that have high housing prices, it would also hit many homeowners who do not view themselves as rich.”

However, the discussion before and after this sentence is obviously referring to investment properties which would be subject to the capital gains tax.]

At least the first $250,000 of gains is exempt for individuals and $500,000 for couples. For this reason, the Post is likely off the mark in telling readers about middle class homeowners rushing to sell their homes to take advantage of the lower capital gains tax rate.

A couple would have to have a gain of at least $500,000 for this to be an issue. That would imply a gain that is a bit less than three times the median house price nationally. That doesn’t sound like a middle class couple. Furthermore, the tax would only apply to the margin over $500,000. That means that a couple selling a home for a gain of $510,000 or $520,000 would be little affected by plausible rises in the capital gains tax rate since they would only pay the higher rate only on the amount over $500,000.

[Correction: The piece is clearly referring to investment properties. I was confused by the sentence:

“The new limit would hit the wealthy hardest, but in regions such as the Washington area that have high housing prices, it would also hit many homeowners who do not view themselves as rich.”

However, the discussion before and after this sentence is obviously referring to investment properties which would be subject to the capital gains tax.]

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión