Former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker is a hero to the inside Washington crowd for having brought down inflation from its double-digit levels of the late 1970s. Never mind that this drop in the inflation rate occurred in every other country in the world also. We still must praise Volcker.

We also should not be bothered by the fact that his policy pushed the unemployment rate to almost 11 percent. This was necessary pain that those outside the elite just had to endure for the good of the country as a whole. We also are not supposed to be bothered by what his high interest policies did to heavily indebted developing countries.

But putting all this aside, the Volcker worshippers should at least be able to get the basic facts right. Steven Pearlstein flunks the test in a WAPO book review when he tells readers:

“By the time he stepped down as Fed chairman in 1987, Volcker had managed to wring inflation out of the American psyche and bring the country’s trade account and the government’s budget much closer toward balance.”

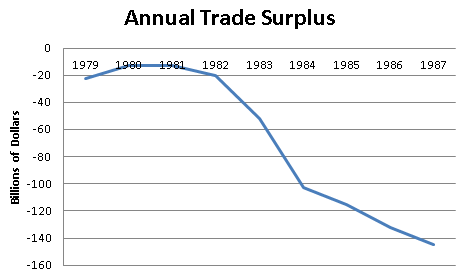

This is not true, the trade deficit in fact soared during the Volcker years as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Expressed as a share of GDP, the trade deficit went from 0.8 percent in 1979 to 3.0 percent in 1987. It really shouldn’t be hard to get this one right.

Addendum:

In response to several comments below I have corrected the graph to show the “surplus” not deficit becoming more negative under Volcker. This was arguably the direct result of his Fed policy, since a predicted result of higher interest rates is a rise in the value of the dollar which makes U.S. goods less competitive internationally.

Former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker is a hero to the inside Washington crowd for having brought down inflation from its double-digit levels of the late 1970s. Never mind that this drop in the inflation rate occurred in every other country in the world also. We still must praise Volcker.

We also should not be bothered by the fact that his policy pushed the unemployment rate to almost 11 percent. This was necessary pain that those outside the elite just had to endure for the good of the country as a whole. We also are not supposed to be bothered by what his high interest policies did to heavily indebted developing countries.

But putting all this aside, the Volcker worshippers should at least be able to get the basic facts right. Steven Pearlstein flunks the test in a WAPO book review when he tells readers:

“By the time he stepped down as Fed chairman in 1987, Volcker had managed to wring inflation out of the American psyche and bring the country’s trade account and the government’s budget much closer toward balance.”

This is not true, the trade deficit in fact soared during the Volcker years as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Expressed as a share of GDP, the trade deficit went from 0.8 percent in 1979 to 3.0 percent in 1987. It really shouldn’t be hard to get this one right.

Addendum:

In response to several comments below I have corrected the graph to show the “surplus” not deficit becoming more negative under Volcker. This was arguably the direct result of his Fed policy, since a predicted result of higher interest rates is a rise in the value of the dollar which makes U.S. goods less competitive internationally.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post is intensifying its push for cuts to Social Security and Medicare apparently hoping for action in the lame duck Congressional session. Today a story in the news section told readers:

“On entitlements, Obama has offered significant changes to Medicare, including letting the eligibility age to rise from 65 to 67.”

The passive tense in this sentence might confuse readers. President Obama proposed raising the eligibility age for Medicare from 65 to 67. This is not something that happens absent his effort to stop it, like the rise of the oceans due to global warming. Obama would be the agent of this increase in the age of eligibility. Experienced reporters and editors usually would not make this sort of mistake.

The next sentence tells readers:

“He has also supported applying a less generous measure of inflation to Social Security benefits.”

Okay, does everyone know what this means? I suspect that only a small minority of Post readers understands that “applying a less generous measure of inflation” implies a cut in the annual cost of living adjustment of 0.3 percentage points. This cut would be cumulative so that after being retired 10 years a beneficiary would see a cut of approximately 3 percent, after 20 years the cut would 6 percent and after 30 years it would be 9 percent.

Newspapers are supposed to be trying to inform their readers. It is difficult to believe that the Post’s terminology in this sentence was its best effort at informing readers of the meaning of this proposal. It is perhaps worth noting that this proposed cut in benefits is hugely unpopular.

At another point the Post discussed the contours of the budget dispute and told readers:

“one of the sticking points remains relevant: Although Democrats wanted to increase the tab [revenue increases] for taxpayers by $800 billion, Republicans wanted at least some of the money to come from economic growth, ….”

A real newspaper would write the second part of this sentence:

“Republicans wanted to claim at least some of the money would come from economic growth”

Undoubtedly both Republicans and Democrats would be happy if the government got additional revenue as a result of more rapid economic growth. The difference is that the Republicans want to score the additional revenue as part of the budget agreement, making assumptions about the impact of lower tax rates on growth that may not be warranted by the evidence. Most Post readers probably would not understand this fact.

The Washington Post is intensifying its push for cuts to Social Security and Medicare apparently hoping for action in the lame duck Congressional session. Today a story in the news section told readers:

“On entitlements, Obama has offered significant changes to Medicare, including letting the eligibility age to rise from 65 to 67.”

The passive tense in this sentence might confuse readers. President Obama proposed raising the eligibility age for Medicare from 65 to 67. This is not something that happens absent his effort to stop it, like the rise of the oceans due to global warming. Obama would be the agent of this increase in the age of eligibility. Experienced reporters and editors usually would not make this sort of mistake.

The next sentence tells readers:

“He has also supported applying a less generous measure of inflation to Social Security benefits.”

Okay, does everyone know what this means? I suspect that only a small minority of Post readers understands that “applying a less generous measure of inflation” implies a cut in the annual cost of living adjustment of 0.3 percentage points. This cut would be cumulative so that after being retired 10 years a beneficiary would see a cut of approximately 3 percent, after 20 years the cut would 6 percent and after 30 years it would be 9 percent.

Newspapers are supposed to be trying to inform their readers. It is difficult to believe that the Post’s terminology in this sentence was its best effort at informing readers of the meaning of this proposal. It is perhaps worth noting that this proposed cut in benefits is hugely unpopular.

At another point the Post discussed the contours of the budget dispute and told readers:

“one of the sticking points remains relevant: Although Democrats wanted to increase the tab [revenue increases] for taxpayers by $800 billion, Republicans wanted at least some of the money to come from economic growth, ….”

A real newspaper would write the second part of this sentence:

“Republicans wanted to claim at least some of the money would come from economic growth”

Undoubtedly both Republicans and Democrats would be happy if the government got additional revenue as a result of more rapid economic growth. The difference is that the Republicans want to score the additional revenue as part of the budget agreement, making assumptions about the impact of lower tax rates on growth that may not be warranted by the evidence. Most Post readers probably would not understand this fact.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The issue arises because Morning Edition decided to lead off its top of the hour news segment by telling listeners of the number of days until we hit the “fiscal cliff.” While one could view this as a random fact, like the number of days until the winter solstice or Super Bowl XLVII, but that is presumably not how it was intended. Most likely this number would be viewed as a countdown against an important deadline.

Of course the end of the year is not an important deadline as every budget expert knows. If there is no deal by the end of the year, we will be subject to a higher rate of tax withholding come January 1, 2013. Since most of us will not get a paycheck on New Year’s Day, we will not be immediately affected by the higher rate of withholding. We would only see an impact when we got our first paycheck of the year in the middle or the end of the month. If Congress and the President work out a deal before that point, there will be no increase in withholding.

Even if a deal is not reached in time to affect the first paycheck, if they come to an agreement later in the month, the extra withholding can be paid back in the second or third paycheck. This is likely to have a minimal impact on the economy, since most people will not change their spending patterns if they expect to get any extra withholding refunded in the near future. For people literally living paycheck to paycheck the extra withholding will be a hardship, but the impact on the economy will be minimal.

There is a similar story with government spending. If it looks like a deal will be reached, President Obama need not adjust the flow of spending at all in January.

For these reasons, there is no special importance to the January 1 deadline. There are of course many political figures, such as the corporate CEOs in the Campaign to Fix the Debt, who are trying to create a crisis atmosphere in order to force an early deal. They hope that this crisis atmosphere can create an environment in which hugely unpopular actions, like cutting Social Security and Medicare, will be possible.

If people at NPR want to support this political effort then they should do it in explicitly labeled commentary. They should not hijack the news section to advance their political agenda.

The issue arises because Morning Edition decided to lead off its top of the hour news segment by telling listeners of the number of days until we hit the “fiscal cliff.” While one could view this as a random fact, like the number of days until the winter solstice or Super Bowl XLVII, but that is presumably not how it was intended. Most likely this number would be viewed as a countdown against an important deadline.

Of course the end of the year is not an important deadline as every budget expert knows. If there is no deal by the end of the year, we will be subject to a higher rate of tax withholding come January 1, 2013. Since most of us will not get a paycheck on New Year’s Day, we will not be immediately affected by the higher rate of withholding. We would only see an impact when we got our first paycheck of the year in the middle or the end of the month. If Congress and the President work out a deal before that point, there will be no increase in withholding.

Even if a deal is not reached in time to affect the first paycheck, if they come to an agreement later in the month, the extra withholding can be paid back in the second or third paycheck. This is likely to have a minimal impact on the economy, since most people will not change their spending patterns if they expect to get any extra withholding refunded in the near future. For people literally living paycheck to paycheck the extra withholding will be a hardship, but the impact on the economy will be minimal.

There is a similar story with government spending. If it looks like a deal will be reached, President Obama need not adjust the flow of spending at all in January.

For these reasons, there is no special importance to the January 1 deadline. There are of course many political figures, such as the corporate CEOs in the Campaign to Fix the Debt, who are trying to create a crisis atmosphere in order to force an early deal. They hope that this crisis atmosphere can create an environment in which hugely unpopular actions, like cutting Social Security and Medicare, will be possible.

If people at NPR want to support this political effort then they should do it in explicitly labeled commentary. They should not hijack the news section to advance their political agenda.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The voters might have told the Republicans that they would have to compromise on their position on taxes, but the Washington Post told them that they don’t. The paper used a news article to imply that congressional Republicans are showing flexibility when they are just repeating the same position they have been putting forward for years. The article told readers:

“chastened Republican leaders have lined up behind Boehner to offer a compromise on taxes, until now a major stumbling block.”

Actually the Republicans are not offering a compromise, they are offering the same position that they offered before and that Governor Romney put forward in his presidential campaign. They are proposing to eliminate some loopholes in exchange for a reduction in tax rates. If the Washington Post is successful in convincing the public that this longstanding Republican position is a compromise, then there will be no need for them to offer a real compromise.

The voters might have told the Republicans that they would have to compromise on their position on taxes, but the Washington Post told them that they don’t. The paper used a news article to imply that congressional Republicans are showing flexibility when they are just repeating the same position they have been putting forward for years. The article told readers:

“chastened Republican leaders have lined up behind Boehner to offer a compromise on taxes, until now a major stumbling block.”

Actually the Republicans are not offering a compromise, they are offering the same position that they offered before and that Governor Romney put forward in his presidential campaign. They are proposing to eliminate some loopholes in exchange for a reduction in tax rates. If the Washington Post is successful in convincing the public that this longstanding Republican position is a compromise, then there will be no need for them to offer a real compromise.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is fashionable in elite circles to talk say that the aging of the population will bankrupt the country as a result of the higher costs it will impose on Social Security and Medicare (referred to as “entitlements.”) It makes you seem a knowledgeable and concerned person to issue dire warnings along these lines.

Of course it is utter nonsense as everyone familiar with the projections knows. The projected rise in Social Security spending due to aging would increase the annual cost of the program by 1.2 percentage points of GDP over the next two decades, roughly two thirds of the increase in military spending associated with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The aging of the population would actually have less impact on Medicare’s costs, except that it is coupled with the expectation that per person health care costs will continue to rise much more rapidly than inflation. However, this means that the Medicare cost problem is a health care cost problem, not a problem due to the aging of the population.

Given this reality is difficult to see why the NYT allowed Jonathan Haidt to say in his oped column:

“we do face bankruptcy when the baby boomers retire and a shrinking percentage of workers must pay the ever growing expenses of a ballooning class of retirees. Yet the Democrats want to “protect” older Americans, students and almost everyone else from the need to sacrifice.”

Haidt obviously wants to make middle class workers sacrifice more than they already have with three decades of wage stagnation, but his rationale is entirely his own invention. There are no remotely plausible projections that show the retirement of the baby boomers bankrupting the country. Insofar as there will be budget problems they are due to the costs of a broken health care system. This requires fixing the health care system, for example by paying doctors and drug companies less.

It is fashionable in elite circles to talk say that the aging of the population will bankrupt the country as a result of the higher costs it will impose on Social Security and Medicare (referred to as “entitlements.”) It makes you seem a knowledgeable and concerned person to issue dire warnings along these lines.

Of course it is utter nonsense as everyone familiar with the projections knows. The projected rise in Social Security spending due to aging would increase the annual cost of the program by 1.2 percentage points of GDP over the next two decades, roughly two thirds of the increase in military spending associated with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The aging of the population would actually have less impact on Medicare’s costs, except that it is coupled with the expectation that per person health care costs will continue to rise much more rapidly than inflation. However, this means that the Medicare cost problem is a health care cost problem, not a problem due to the aging of the population.

Given this reality is difficult to see why the NYT allowed Jonathan Haidt to say in his oped column:

“we do face bankruptcy when the baby boomers retire and a shrinking percentage of workers must pay the ever growing expenses of a ballooning class of retirees. Yet the Democrats want to “protect” older Americans, students and almost everyone else from the need to sacrifice.”

Haidt obviously wants to make middle class workers sacrifice more than they already have with three decades of wage stagnation, but his rationale is entirely his own invention. There are no remotely plausible projections that show the retirement of the baby boomers bankrupting the country. Insofar as there will be budget problems they are due to the costs of a broken health care system. This requires fixing the health care system, for example by paying doctors and drug companies less.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT has an article that discussed the possibility that China’s economy will be less focused on investment and more focused on consumption and improving the quality of life of the Chinese people. It notes the extraordinary share of GDP in China that is devoted to investment and includes a graph that shows in the 1980s both Japan and South Korea also had an extraordinary share of GDP devoted to investment. It then tells readers that:

“Growth in Japan and South Korea started to slow and eventually tumbled after investment peaked. The big question now is when China will run into the same limits, …”

This is not quite right. While Japan did have a sharp slowdown in growth following the collapse of its stock and real estate bubbles in 1990, South Korea has continued to maintain a healthy growth rate following the peak of investment in 1990. The point is important, because the NYT characterization of the situation implies that China faces an inevitable crisis while the experience of South Korea suggests that China could transition to a path of healthy growth that is less driven by investment.

The NYT has an article that discussed the possibility that China’s economy will be less focused on investment and more focused on consumption and improving the quality of life of the Chinese people. It notes the extraordinary share of GDP in China that is devoted to investment and includes a graph that shows in the 1980s both Japan and South Korea also had an extraordinary share of GDP devoted to investment. It then tells readers that:

“Growth in Japan and South Korea started to slow and eventually tumbled after investment peaked. The big question now is when China will run into the same limits, …”

This is not quite right. While Japan did have a sharp slowdown in growth following the collapse of its stock and real estate bubbles in 1990, South Korea has continued to maintain a healthy growth rate following the peak of investment in 1990. The point is important, because the NYT characterization of the situation implies that China faces an inevitable crisis while the experience of South Korea suggests that China could transition to a path of healthy growth that is less driven by investment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Michael Gerson used his column today to make a bizarre attack on the NYT’s polling analyst Nate Silver. He complains to readers:

“Silver’s prediction is not an innovation; it is trend taken to its absurd extreme. He is doing little more than weighting and aggregating state polls and combining them with various historical assumptions to project a future outcome to project a future outcome with exaggerated, attention-grabbing exactitude. His work is better summarized as an 86.3 percent confidence that the state polls are correct.”

Actually Silver is doing nothing more than weighting and aggregating state polls and combining them with various historical assumptions. He is very clear on this. Gerson can go to Silver’s website and find in great detail the methodology that Silver uses for weighting various polls based on their past track records. Gerson apparently thinks this is an indictment, complaining about Silver’s precise 86.3 percent probability estimate.

The real problem here is simply that Gerson does not understand what Silver is doing. Silver’s 86.3 percent prediction is premised on the assumption that the polls do not contain a systemic bias and that there is not some event(s) that radically shifts the attitude of the electorate between the last round of polls and the election. With these assumptions we can treat the polls as comparable to the draw of white and black marbles out of a huge jar.

If we take enough draws of 1000 balls (you’re welcome to use a different number) and the average of each of these draws is that 50.5 percent of the marbles are black, we can begin to say with great confidence (which can be specified with many decimal points) that the majority of the marbles in this huge jar are in fact black. This is what Nate is doing. He does adjust the draws — some polls consistently find more white or black marbles than the average of the other polls. Unless these polls have proved to be accurate in these divergences, Nate makes an adjustment for their tendency to find too many white or black balls. This process is the value-added that Nate provides over a simple averaging of the various polls.

This doesn’t guarantee that Nate will prove right. There could be some systemic bias in the polls. This would be comparable to a situation where the black balls are heavier and therefore fall to the bottom and are less likely to be in the draw. The way to argue this case is to present a reason for why the polls could be biased. There are possible stories here: voters with only a cell phone may be undercounted, the assumptions about who is a likely voter may prove wrong, or the polls may be undercounting Spanish speaking voters.

These factors, and others, could lead to a systemic bias in the polls. But if Gerson, or anyone else, thinks this is the issue now, then it is incumbent on them to make the case, not get angry at Silver for using statistical methods.

The real problem is that Gerson just seems to have difficulty with numbers. He concludes his piece by telling readers:

“And so, at the election’s close, we talk of Silver’s statistical model and the likely turnout in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, and relatively little about poverty, social mobility or unsustainable debt.”

Yes, it would be great if we had more discussion of poverty and social mobility throughout the campaign and beyond. It’s hard to blame Silver for the lack of such discussion. The pre-Silver elections were not exactly dominated by serious discussions of major national issues. I recall in the 1988 presidential election when the big issues in the race between George H.W. Bush and Michael Dukakis were Willy Horton and the pledge of allegiance.

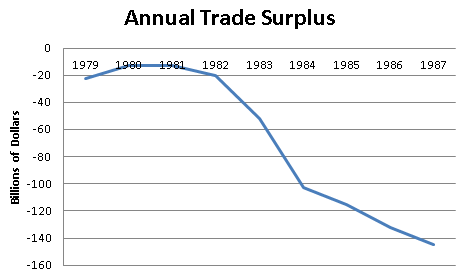

As far as the third item on Gerson’s list, unsustainable debt, this is where his knowledge of math again fails him. Here is the ratio of interest payments to GDP over the last four decades:

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

As can be seen, the debt burden is very far from unsustainable, the interest burden is near its post-war low. In other words Gerson is angry because he thinks that somehow Silver’s polling analysis has diverted the country from discussing a non-existent problem.

Michael Gerson used his column today to make a bizarre attack on the NYT’s polling analyst Nate Silver. He complains to readers:

“Silver’s prediction is not an innovation; it is trend taken to its absurd extreme. He is doing little more than weighting and aggregating state polls and combining them with various historical assumptions to project a future outcome to project a future outcome with exaggerated, attention-grabbing exactitude. His work is better summarized as an 86.3 percent confidence that the state polls are correct.”

Actually Silver is doing nothing more than weighting and aggregating state polls and combining them with various historical assumptions. He is very clear on this. Gerson can go to Silver’s website and find in great detail the methodology that Silver uses for weighting various polls based on their past track records. Gerson apparently thinks this is an indictment, complaining about Silver’s precise 86.3 percent probability estimate.

The real problem here is simply that Gerson does not understand what Silver is doing. Silver’s 86.3 percent prediction is premised on the assumption that the polls do not contain a systemic bias and that there is not some event(s) that radically shifts the attitude of the electorate between the last round of polls and the election. With these assumptions we can treat the polls as comparable to the draw of white and black marbles out of a huge jar.

If we take enough draws of 1000 balls (you’re welcome to use a different number) and the average of each of these draws is that 50.5 percent of the marbles are black, we can begin to say with great confidence (which can be specified with many decimal points) that the majority of the marbles in this huge jar are in fact black. This is what Nate is doing. He does adjust the draws — some polls consistently find more white or black marbles than the average of the other polls. Unless these polls have proved to be accurate in these divergences, Nate makes an adjustment for their tendency to find too many white or black balls. This process is the value-added that Nate provides over a simple averaging of the various polls.

This doesn’t guarantee that Nate will prove right. There could be some systemic bias in the polls. This would be comparable to a situation where the black balls are heavier and therefore fall to the bottom and are less likely to be in the draw. The way to argue this case is to present a reason for why the polls could be biased. There are possible stories here: voters with only a cell phone may be undercounted, the assumptions about who is a likely voter may prove wrong, or the polls may be undercounting Spanish speaking voters.

These factors, and others, could lead to a systemic bias in the polls. But if Gerson, or anyone else, thinks this is the issue now, then it is incumbent on them to make the case, not get angry at Silver for using statistical methods.

The real problem is that Gerson just seems to have difficulty with numbers. He concludes his piece by telling readers:

“And so, at the election’s close, we talk of Silver’s statistical model and the likely turnout in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, and relatively little about poverty, social mobility or unsustainable debt.”

Yes, it would be great if we had more discussion of poverty and social mobility throughout the campaign and beyond. It’s hard to blame Silver for the lack of such discussion. The pre-Silver elections were not exactly dominated by serious discussions of major national issues. I recall in the 1988 presidential election when the big issues in the race between George H.W. Bush and Michael Dukakis were Willy Horton and the pledge of allegiance.

As far as the third item on Gerson’s list, unsustainable debt, this is where his knowledge of math again fails him. Here is the ratio of interest payments to GDP over the last four decades:

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

As can be seen, the debt burden is very far from unsustainable, the interest burden is near its post-war low. In other words Gerson is angry because he thinks that somehow Silver’s polling analysis has diverted the country from discussing a non-existent problem.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s best to ignore personal slights in Washington and elsewhere, but this one goes beyond my personal feelings. In a review of Nate Silver’s new book, Noam Scheiber notes the effectiveness with which Silver uses data to analyze a wide range of policy issues and then tells us:

“it’s not hard to imagine Silver and his ilk one day letting the air out of an inflating housing bubble.”

Yeah, right. It shouldn’t be too hard to imagine since that is what some of us were trying to do from 2002 onward. The remarkable story here is that we were ignored at the time and are apparently still ignored even after the fact by people who have the credentials to write in the NYT.

There is an interesting sociology of knowledge story here. How is that history can be completely rewritten? The problem was not that people were not making the case that we had an unsustainable housing bubble. The problem was that people with authority chose to ignore the people making the case that there was a bubble. And even now they can claim that the people warning about the bubble did not exist.

This works out well for the bubble deniers since it makes it easier to claim the “who could have known?” defense. But it is not true, and it is outrageous that Scheiber could ignorantly write something like this and the NYT book editor could allow it into print.

It’s best to ignore personal slights in Washington and elsewhere, but this one goes beyond my personal feelings. In a review of Nate Silver’s new book, Noam Scheiber notes the effectiveness with which Silver uses data to analyze a wide range of policy issues and then tells us:

“it’s not hard to imagine Silver and his ilk one day letting the air out of an inflating housing bubble.”

Yeah, right. It shouldn’t be too hard to imagine since that is what some of us were trying to do from 2002 onward. The remarkable story here is that we were ignored at the time and are apparently still ignored even after the fact by people who have the credentials to write in the NYT.

There is an interesting sociology of knowledge story here. How is that history can be completely rewritten? The problem was not that people were not making the case that we had an unsustainable housing bubble. The problem was that people with authority chose to ignore the people making the case that there was a bubble. And even now they can claim that the people warning about the bubble did not exist.

This works out well for the bubble deniers since it makes it easier to claim the “who could have known?” defense. But it is not true, and it is outrageous that Scheiber could ignorantly write something like this and the NYT book editor could allow it into print.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post has repeatedly used its news section (e.g here and here) to hype fears about the budget dispute that it likes to call the “fiscal cliff.” (Since the actual impact of waiting until after the end of the year to reach a deal is minor, most objective commentators would not use the term “cliff” to refer to the deadline.) If the consequences of waiting until after the end of the year to make a deal, when the politics shift to President Obama’s favor, can be portrayed as sufficiently dire then the Post presumably hopes that it can force a deal that will be closer to the Republicans’ terms.

It was pushing this line again today with a piece warning of a disaster if Congress does not pass a fix to the alternative minimum tax by the end of the year. The issue is that the tax was not adjusted for inflation for 2012 so many middle income households would be subject to the alternative minimum tax who were not intended to be hit by it.

The piece does its best to overstate the dire consequences for waiting after the end of the year. Most importantly it gives the number of people affected and then gives the average tax additional liability telling us in the second paragraph:

“Unless Congress acts by the end of the year, more than 26 million households will for the first time face the AMT, which threatens to tack $3,700, on average, onto taxpayers’ bills for the current tax year.”

In fact most of these 26 million households would face very limited tax increases, but some taxpayers may find themselves with a substantial increase in liabilities. The piece also warns that if Congress waits until after the end of the year to resolve the issue then refunds could be delayed by a month or two. It then informs readers that many taxpayers use refunds to pay essential bills like gas and electric bills and will risk having service disconnected if they have to wait longer for their refunds. Of course the refunds will go almost exclusively to families with incomes of more than $75,000 a year. It is not likely that many people in this income category are facing the cutoff of utilities.

The piece also raises the risk that many taxpayers may be subject to penalties for failing to withhold based on their higher liability. It would be a very simple matter for Congress to include a provision in any measure passed in January that exempted taxpayers from such penalties.

This is the sort of piece that makes it clear that Post would like to see the budget dispute resolved on conditions favorable to the Republicans. It doesn’t belong in the news section of a serious newspaper.

The Washington Post has repeatedly used its news section (e.g here and here) to hype fears about the budget dispute that it likes to call the “fiscal cliff.” (Since the actual impact of waiting until after the end of the year to reach a deal is minor, most objective commentators would not use the term “cliff” to refer to the deadline.) If the consequences of waiting until after the end of the year to make a deal, when the politics shift to President Obama’s favor, can be portrayed as sufficiently dire then the Post presumably hopes that it can force a deal that will be closer to the Republicans’ terms.

It was pushing this line again today with a piece warning of a disaster if Congress does not pass a fix to the alternative minimum tax by the end of the year. The issue is that the tax was not adjusted for inflation for 2012 so many middle income households would be subject to the alternative minimum tax who were not intended to be hit by it.

The piece does its best to overstate the dire consequences for waiting after the end of the year. Most importantly it gives the number of people affected and then gives the average tax additional liability telling us in the second paragraph:

“Unless Congress acts by the end of the year, more than 26 million households will for the first time face the AMT, which threatens to tack $3,700, on average, onto taxpayers’ bills for the current tax year.”

In fact most of these 26 million households would face very limited tax increases, but some taxpayers may find themselves with a substantial increase in liabilities. The piece also warns that if Congress waits until after the end of the year to resolve the issue then refunds could be delayed by a month or two. It then informs readers that many taxpayers use refunds to pay essential bills like gas and electric bills and will risk having service disconnected if they have to wait longer for their refunds. Of course the refunds will go almost exclusively to families with incomes of more than $75,000 a year. It is not likely that many people in this income category are facing the cutoff of utilities.

The piece also raises the risk that many taxpayers may be subject to penalties for failing to withhold based on their higher liability. It would be a very simple matter for Congress to include a provision in any measure passed in January that exempted taxpayers from such penalties.

This is the sort of piece that makes it clear that Post would like to see the budget dispute resolved on conditions favorable to the Republicans. It doesn’t belong in the news section of a serious newspaper.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión