Mark Zandi is anxious to give President Obama credit for the first time homebuyers tax credit, arguing that it helped stop the free fall in house prices. Actually, blame would be more appropriate. The credit was offered at a time when the bubble was still far from having fully deflated. The credit was not going to maintain house prices at a permanently inflated level unless the government was prepared to go the route of a house price support program. (This would be sort of like out farm price support programs, except it would be a lot more costly and would redistribute much more money upward.).

The main effect of the credit, as Zandi notes, was to pull people into the market earlier than would have otherwise been the case. As a result, many first-time homebuyers paid bubble inflated prices for houses. The price declines resumed as soon as the credit expired. When the deflation of the bubble had been completed many saw price declines on their homes that were two or three times the size of the credit. This loss was a totally predictable effect from offering the credit in a market where the bubble was still in the process of deflating.

The credit did not have any lasting effect on the housing market. It just transferred wealth from the government to homeowners wishing to sell and to banks and other mortgage holders who might otherwise have been forced to accept short sales. It is hard to see any positive effects from this policy.

Mark Zandi is anxious to give President Obama credit for the first time homebuyers tax credit, arguing that it helped stop the free fall in house prices. Actually, blame would be more appropriate. The credit was offered at a time when the bubble was still far from having fully deflated. The credit was not going to maintain house prices at a permanently inflated level unless the government was prepared to go the route of a house price support program. (This would be sort of like out farm price support programs, except it would be a lot more costly and would redistribute much more money upward.).

The main effect of the credit, as Zandi notes, was to pull people into the market earlier than would have otherwise been the case. As a result, many first-time homebuyers paid bubble inflated prices for houses. The price declines resumed as soon as the credit expired. When the deflation of the bubble had been completed many saw price declines on their homes that were two or three times the size of the credit. This loss was a totally predictable effect from offering the credit in a market where the bubble was still in the process of deflating.

The credit did not have any lasting effect on the housing market. It just transferred wealth from the government to homeowners wishing to sell and to banks and other mortgage holders who might otherwise have been forced to accept short sales. It is hard to see any positive effects from this policy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is remarkable how people keep insisting, in spite of all the evidence to the contrary, that the problem of the downturn is a financial crisis rather than simply a collapsed housing bubble. The latter story is simple. Housing construction was driven by bubble-inflated prices. When prices plunged, construction collapsed. Not only did we no longer have inflated prices to drive construction, we also had an enormous oversupply as a result of 5 years of near record rates of construction. From 2006 to 2009 construction fell by more than 4 percentage points of GDP, leading to a loss of more than $600 billion in annual demand.

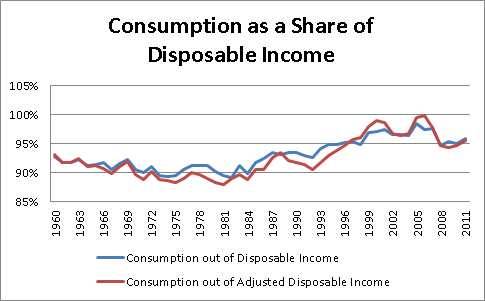

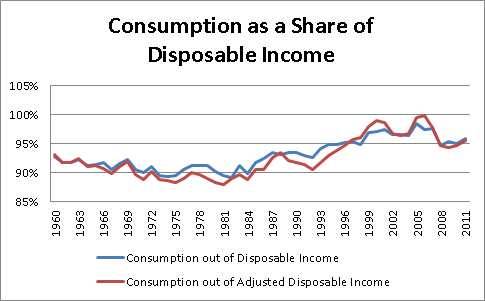

In addition, the loss of $8 trillion in housing wealth lead to sharp falloff in consumption. While the housing wealth effect is a long-established and widely accepted economic phenomenon, most discussions of the financial crisis act as though this effect does not exist. The wealth created by the run-up in house prices led to a consumption boom as the saving rate fell to near zero. With the collapse of the bubble, consumption fell back as the wealth that has been driving it disappeared.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

However, contrary to what is widely asserted, for example by David Leonhardt in his column today, consumption remains high, not low. The saving rate averaged more than 8.0 percent of disposable income in the years prior to the rise of the stock bubble in the 90s. Currently, it is between 4 and 5 percent of disposable income. If anything, we should be asking why consumption is so high, not why it is low.

It would be too absurd to expect bubble levels of consumption in the absence of the bubble. However this is what proponents of the financial crisis theory seem to be arguing. In short, the collapse of the bubble led to a gap of more than $1 trillion in lost demand due to the plunge in construction and the falloff in consumption. What if any part of this requires a story about the financial crisis?

It is remarkable how people keep insisting, in spite of all the evidence to the contrary, that the problem of the downturn is a financial crisis rather than simply a collapsed housing bubble. The latter story is simple. Housing construction was driven by bubble-inflated prices. When prices plunged, construction collapsed. Not only did we no longer have inflated prices to drive construction, we also had an enormous oversupply as a result of 5 years of near record rates of construction. From 2006 to 2009 construction fell by more than 4 percentage points of GDP, leading to a loss of more than $600 billion in annual demand.

In addition, the loss of $8 trillion in housing wealth lead to sharp falloff in consumption. While the housing wealth effect is a long-established and widely accepted economic phenomenon, most discussions of the financial crisis act as though this effect does not exist. The wealth created by the run-up in house prices led to a consumption boom as the saving rate fell to near zero. With the collapse of the bubble, consumption fell back as the wealth that has been driving it disappeared.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

However, contrary to what is widely asserted, for example by David Leonhardt in his column today, consumption remains high, not low. The saving rate averaged more than 8.0 percent of disposable income in the years prior to the rise of the stock bubble in the 90s. Currently, it is between 4 and 5 percent of disposable income. If anything, we should be asking why consumption is so high, not why it is low.

It would be too absurd to expect bubble levels of consumption in the absence of the bubble. However this is what proponents of the financial crisis theory seem to be arguing. In short, the collapse of the bubble led to a gap of more than $1 trillion in lost demand due to the plunge in construction and the falloff in consumption. What if any part of this requires a story about the financial crisis?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

David Brooks on raising the age of eligibility for Social Security and Medicare:

“Have you looked at 67-year-olds recently? They look the way 40-year-olds used to look.”

David Brooks on raising the age of eligibility for Social Security and Medicare:

“Have you looked at 67-year-olds recently? They look the way 40-year-olds used to look.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Ruth Marcus commits just about every major error in budget analysis in her Washington Post column this morning. To start with, she warns of the fiscal cliff at the end of the year:

“A fiscal cliff looms at year’s end, when a cornucopia of tax cuts is set to expire and a $1.2?trillion spending sequester kicks in. Like Wile E. Coyote, we are about to suddenly look down at a gaping void.”

Wow, that sounds really scary. Of course this is the sort of nonsense that can only appear in the Washington Post and similar publications. Contrary to what Marcus wants us to believe, there is no Wile E. Coyote moment waiting at year-end. On the tax side, beginning in January we would start to see more money deducted from our paychecks. Since most of us are not paid in advance, we would first begin to see any effect on the tax side when we get our paychecks at the middle or end of the month. If there is an expectation that Congress and the President are likely to work out a deal that preserves most of the current tax cuts, then the impact on consumer spending and the economy in January will be close to zero.

On the spending side, the $1.2 trillion figure is one that makes sense if we assume that Congress will never revisit spending policy over the next decade. That’s right, it has nothing to do with January of 2013, it refers to spending over the next decade. (Hey, this is the Washington Post.) The actual impact on spending in January is likely to be minimal, unless President Obama wants to slow spending to make a point. (The president has enormous control over the timing of spending.)

In short, there is nothing resembling a cliff or a Wile E. Coyote moment, these are fictions that only exist in the Washington Post and similar locations. The purpose of this fabrication is to advance their agenda for their preferred plan for spending cuts and tax increases. As Marcus tells us in the next paragraph:

“Behind the scenes, serious people in the administration and Congress, of both parties, are discussing ways to avert the economic shock of suddenly hiking taxes and throttling back spending. But there can be no pathway to success unless enough partisans on both sides give up on their foundational myths: for Republicans, that the fiscal challenge can be solved through spending cuts alone; for Democrats, that tax increases on the wealthy will suffice (emphasis added).”

Yes, thank God for serious people. You would recognize these serious people as the folks that were too thick to recognize the $8 trillion housing bubble, the collapse of which wrecked the economy; oh, and by the way, also gave us trillion dollar annual deficits. They were too busy yelling about budget deficits. (I’m not kidding, they were screaming about budget deficits even when the deficit was less than 2.0 percent of GDP.)

Contrary to what Marcus and the Serious People want people to believe, there is no spending problem, there is a problem of out of control health care costs. The United States pays more than twice as much per person for its health care as the average for people in other wealthy countries, with little to show in the way of health outcomes. If we paid the same amount as any other wealthy country we would be looking at huge budget surpluses, not deficits.

The deception here is simple and extremely important. Honest people would talk about the need to reform the health care system. That addresses the health care cost problem that the country really does face. Marcus and the Serious People would instead want to leave the broken system intact and just have the government pick up less of the tab.

This difference has enormous implications not only for access to health care but also for the distribution of income. Fixing the health care system means whacking the bloated incomes received by the drug industry, the insurance industry, the medical equipment industry and doctors (especially highly paid medical specialists). The route chosen by Marcus and the Serious People protects the income of these people. It instead will force lower and middle income people to get by without adequate care. This is the choice that the Post is doing its best to conceal from its readers.

Ruth Marcus commits just about every major error in budget analysis in her Washington Post column this morning. To start with, she warns of the fiscal cliff at the end of the year:

“A fiscal cliff looms at year’s end, when a cornucopia of tax cuts is set to expire and a $1.2?trillion spending sequester kicks in. Like Wile E. Coyote, we are about to suddenly look down at a gaping void.”

Wow, that sounds really scary. Of course this is the sort of nonsense that can only appear in the Washington Post and similar publications. Contrary to what Marcus wants us to believe, there is no Wile E. Coyote moment waiting at year-end. On the tax side, beginning in January we would start to see more money deducted from our paychecks. Since most of us are not paid in advance, we would first begin to see any effect on the tax side when we get our paychecks at the middle or end of the month. If there is an expectation that Congress and the President are likely to work out a deal that preserves most of the current tax cuts, then the impact on consumer spending and the economy in January will be close to zero.

On the spending side, the $1.2 trillion figure is one that makes sense if we assume that Congress will never revisit spending policy over the next decade. That’s right, it has nothing to do with January of 2013, it refers to spending over the next decade. (Hey, this is the Washington Post.) The actual impact on spending in January is likely to be minimal, unless President Obama wants to slow spending to make a point. (The president has enormous control over the timing of spending.)

In short, there is nothing resembling a cliff or a Wile E. Coyote moment, these are fictions that only exist in the Washington Post and similar locations. The purpose of this fabrication is to advance their agenda for their preferred plan for spending cuts and tax increases. As Marcus tells us in the next paragraph:

“Behind the scenes, serious people in the administration and Congress, of both parties, are discussing ways to avert the economic shock of suddenly hiking taxes and throttling back spending. But there can be no pathway to success unless enough partisans on both sides give up on their foundational myths: for Republicans, that the fiscal challenge can be solved through spending cuts alone; for Democrats, that tax increases on the wealthy will suffice (emphasis added).”

Yes, thank God for serious people. You would recognize these serious people as the folks that were too thick to recognize the $8 trillion housing bubble, the collapse of which wrecked the economy; oh, and by the way, also gave us trillion dollar annual deficits. They were too busy yelling about budget deficits. (I’m not kidding, they were screaming about budget deficits even when the deficit was less than 2.0 percent of GDP.)

Contrary to what Marcus and the Serious People want people to believe, there is no spending problem, there is a problem of out of control health care costs. The United States pays more than twice as much per person for its health care as the average for people in other wealthy countries, with little to show in the way of health outcomes. If we paid the same amount as any other wealthy country we would be looking at huge budget surpluses, not deficits.

The deception here is simple and extremely important. Honest people would talk about the need to reform the health care system. That addresses the health care cost problem that the country really does face. Marcus and the Serious People would instead want to leave the broken system intact and just have the government pick up less of the tab.

This difference has enormous implications not only for access to health care but also for the distribution of income. Fixing the health care system means whacking the bloated incomes received by the drug industry, the insurance industry, the medical equipment industry and doctors (especially highly paid medical specialists). The route chosen by Marcus and the Serious People protects the income of these people. It instead will force lower and middle income people to get by without adequate care. This is the choice that the Post is doing its best to conceal from its readers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The coal industry has spent tens of millions of dollars trying to convince people that the country should not take measures to stop global warming. NPR contributed to this campaign by running a piece on the politics of Ohio in the election which implied that coal was central to the state’s economy or at least to the area around Akron.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Ohio has approximately 12,000 employed in mining and logging. Presumably the vast majority of these workers are employed in coal mining. If we assume that all of them are employed in mining then this would be a bit more than 0.2 percent of its 5.2 million workers.

Turning to the Akron area, BLS doesn’t break out mining and logging separately, but tells us that around 12,000 workers are employed in construction, mining, and logging. If we assume that construction accounts for 3 percent of total employment (roughly the national average), this would leave a bit less than 3,000 workers employed in mining, around 1 percent of its total employment of 320,000.

While the coal industry may want us to believe that the region’s economy depends on a sector that accounts for less than 1 percent of total employment, that is not a plausible story. NPR should not have uncritically presented the industry’s claims about its importance to the region’s economy.

The coal industry has spent tens of millions of dollars trying to convince people that the country should not take measures to stop global warming. NPR contributed to this campaign by running a piece on the politics of Ohio in the election which implied that coal was central to the state’s economy or at least to the area around Akron.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Ohio has approximately 12,000 employed in mining and logging. Presumably the vast majority of these workers are employed in coal mining. If we assume that all of them are employed in mining then this would be a bit more than 0.2 percent of its 5.2 million workers.

Turning to the Akron area, BLS doesn’t break out mining and logging separately, but tells us that around 12,000 workers are employed in construction, mining, and logging. If we assume that construction accounts for 3 percent of total employment (roughly the national average), this would leave a bit less than 3,000 workers employed in mining, around 1 percent of its total employment of 320,000.

While the coal industry may want us to believe that the region’s economy depends on a sector that accounts for less than 1 percent of total employment, that is not a plausible story. NPR should not have uncritically presented the industry’s claims about its importance to the region’s economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Commerce Department reported that durable goods orders fell by 13.2 percent in August, not surprisingly the Wall Street Journal chose to highlight this drop. While the number is dramatic, nearly all of the drop was in the highly volatile transportation component. Excluding transportation, orders fell by a considerably more modest 1.6 percent.

Within transportation, civilian aircraft stood out with a decline in orders of 101.8 percent. Yes, the number was over 100 percent, as apparently there were more orders canceled in August than added.

Clearly there are some issues of timing here, but at the moment not very much cause for concern. If we want to know how businesses are thinking about the future, we might look at orders for non-defense capital goods, excluding aircraft, which rose by 1.1 percent in August, albeit after two sharp monthly declines. Anyhow, the overall picture in this report is negative but certainly not the disaster that the WSJ article implies. Given that weekly unemployment claims hit a new low for the recovery, a wait for evidence view might be appropriate.

Correction: Bill Heffner’s comment below is right. The 359,000 claims reported in the most recent week is higher than two week in July, in which the number of claimsreported were 352,000 and 357,000. It is worth noting that claims are almost always revised upward, but usually by a small amount.

The Commerce Department reported that durable goods orders fell by 13.2 percent in August, not surprisingly the Wall Street Journal chose to highlight this drop. While the number is dramatic, nearly all of the drop was in the highly volatile transportation component. Excluding transportation, orders fell by a considerably more modest 1.6 percent.

Within transportation, civilian aircraft stood out with a decline in orders of 101.8 percent. Yes, the number was over 100 percent, as apparently there were more orders canceled in August than added.

Clearly there are some issues of timing here, but at the moment not very much cause for concern. If we want to know how businesses are thinking about the future, we might look at orders for non-defense capital goods, excluding aircraft, which rose by 1.1 percent in August, albeit after two sharp monthly declines. Anyhow, the overall picture in this report is negative but certainly not the disaster that the WSJ article implies. Given that weekly unemployment claims hit a new low for the recovery, a wait for evidence view might be appropriate.

Correction: Bill Heffner’s comment below is right. The 359,000 claims reported in the most recent week is higher than two week in July, in which the number of claimsreported were 352,000 and 357,000. It is worth noting that claims are almost always revised upward, but usually by a small amount.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Those who wonder why the Post seems to focus obsessively on budget deficits when there are so many larger problems afflicting the country got part of their answer today in an article on the euro crisis. The article focuses exclusively on budget deficits and the risk of insolvency for the troubled economies of southern Europe. It never once raises the issue of the current account deficits that these countries are experiencing.

The fundamental problem in the euro zone is that costs in southern Europe have risen sharply relative to costs in Germany over the last decade. This makes southern Europe less competitive, leading to its large trade deficit. The trade deficit, implies negative national savings (i.e. there is no possible around this outcome). Negative national savings means either that private investment exceeds private savings (which was true in the bubble years) and/or budget deficits. Unless the trade deficit is reduced in these countries, there is no plausible way to get the budget deficits down.

The current route in to lower deficits is by shrinking the economy and thereby reducing private savings. It is not a plausible long-term strategy. Ultimately it will be necessary for costs in Germany and the south to move closer together. It is very difficult to get prices to fall, which means that Germany has no choice but to experience higher inflation.

But Post readers didn’t hear about this issue. They were just told about budget deficits.

Those who wonder why the Post seems to focus obsessively on budget deficits when there are so many larger problems afflicting the country got part of their answer today in an article on the euro crisis. The article focuses exclusively on budget deficits and the risk of insolvency for the troubled economies of southern Europe. It never once raises the issue of the current account deficits that these countries are experiencing.

The fundamental problem in the euro zone is that costs in southern Europe have risen sharply relative to costs in Germany over the last decade. This makes southern Europe less competitive, leading to its large trade deficit. The trade deficit, implies negative national savings (i.e. there is no possible around this outcome). Negative national savings means either that private investment exceeds private savings (which was true in the bubble years) and/or budget deficits. Unless the trade deficit is reduced in these countries, there is no plausible way to get the budget deficits down.

The current route in to lower deficits is by shrinking the economy and thereby reducing private savings. It is not a plausible long-term strategy. Ultimately it will be necessary for costs in Germany and the south to move closer together. It is very difficult to get prices to fall, which means that Germany has no choice but to experience higher inflation.

But Post readers didn’t hear about this issue. They were just told about budget deficits.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Raleigh News and Observer has a nice piece on how the large hospitals in the state make big profits on chemotherapy drugs. Yes, this is the sort of thing one expects when the government grants patent monopolies. Where are the foes of big government?

[Correction: I had earlier identified the paper as the Charlotte Observer.]

The Raleigh News and Observer has a nice piece on how the large hospitals in the state make big profits on chemotherapy drugs. Yes, this is the sort of thing one expects when the government grants patent monopolies. Where are the foes of big government?

[Correction: I had earlier identified the paper as the Charlotte Observer.]

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT notes that the deficit is likely to surpass $1 trillion for the fourth consecutive year. It then tells readers:

“Against that headline-grabbing figure, Mr. Obama’s explanation — that the deficit he inherited is actually on a path to be cut in half just a year later than he promised, measured as a percentage of the economy’s total output — risks sounding professorial at best.”

Many people might have thought that newspapers control what goes into their headlines (the headline of this piece is “Obama faces test as deficit stays above $1 trillion). This should mean that they have the ability to write their headlines and articles in ways that best convey information to readers, not fan fears that are promoted by partisans of a particular course of action (i.e. deficit reduction). This means that if President Obama’s explanation for the deficit is valid (it is), then it is the responsibility of the paper to explain it to readers in a way that is understandable to them.

The piece notes projected increases in the ratio of debt to GDP. It then tells readers:

“Many analysts say that a nation’s debt should not exceed 60 percent to 70 percent.”

While it does not identify these analysts, they are obviously people who are ill-informed about budget accounting. If we are only concerned about the ratio of debt to GDP, then the Treasury will be able to buy back long-term debt issued today at very low interest rates at a substantial discount if interest rates rise back to more normal levels as predicted by the Congressional Budget Office and others.

A 30-year bond issued at a 2.75 percent interest rate, would sell at a 40 percent discount if the long-term interest rate rose to a more normal 6.0 percent. This means that if the Treasury had $4 trillion in 30-year bonds outstanding, it would be able to buy them back for 2.4 billion, instantly eliminating $1.6 trillion in debt or roughly 10 percentage points of GDP.

This would of course be silly, the interest burden would not have changed, but budget analysts who think that a nation’s debt should not exceed 60 percent to 70 percent would be made very happy by this action. In reality what matters is the ratio of interest payments to GDP, which is now near a post-World War II low. Remarkably, this fact is never mentioned in this piece.

The NYT notes that the deficit is likely to surpass $1 trillion for the fourth consecutive year. It then tells readers:

“Against that headline-grabbing figure, Mr. Obama’s explanation — that the deficit he inherited is actually on a path to be cut in half just a year later than he promised, measured as a percentage of the economy’s total output — risks sounding professorial at best.”

Many people might have thought that newspapers control what goes into their headlines (the headline of this piece is “Obama faces test as deficit stays above $1 trillion). This should mean that they have the ability to write their headlines and articles in ways that best convey information to readers, not fan fears that are promoted by partisans of a particular course of action (i.e. deficit reduction). This means that if President Obama’s explanation for the deficit is valid (it is), then it is the responsibility of the paper to explain it to readers in a way that is understandable to them.

The piece notes projected increases in the ratio of debt to GDP. It then tells readers:

“Many analysts say that a nation’s debt should not exceed 60 percent to 70 percent.”

While it does not identify these analysts, they are obviously people who are ill-informed about budget accounting. If we are only concerned about the ratio of debt to GDP, then the Treasury will be able to buy back long-term debt issued today at very low interest rates at a substantial discount if interest rates rise back to more normal levels as predicted by the Congressional Budget Office and others.

A 30-year bond issued at a 2.75 percent interest rate, would sell at a 40 percent discount if the long-term interest rate rose to a more normal 6.0 percent. This means that if the Treasury had $4 trillion in 30-year bonds outstanding, it would be able to buy them back for 2.4 billion, instantly eliminating $1.6 trillion in debt or roughly 10 percentage points of GDP.

This would of course be silly, the interest burden would not have changed, but budget analysts who think that a nation’s debt should not exceed 60 percent to 70 percent would be made very happy by this action. In reality what matters is the ratio of interest payments to GDP, which is now near a post-World War II low. Remarkably, this fact is never mentioned in this piece.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Casey Mulligan takes another stab at explaining the drop in employment since the housing market crash on changes in incentives in the NYT today. The basic story is that the extension of the length of unemployment insurance (UI), the easing of eligibility rules, the increased generosity of food stamps and several other changes in tax and benefit structures gave people less incentive to work. As a result, more people opted to rely on these benefits rather than work, hence the large falloff in employment and the rise in the unemployment rate.

There are many problems with this story, most importantly that people who have looked at what happens to workers whose UI benefits expire (e.g. Jesse Rothstein) find that most of them simply leave the labor force. They do not suddenly start working. Since the extension of UI benefits was by far the most important change in incentives since the start of the downturn, and we don’t see much evidence of an effect on employment, we might have some reason to believe that the other smaller changes had much effect.

But Mulligan presents us with a graph that shows that groups that saw larger increases in effective tax rates (which includes the loss of benefits from working as an implicit tax) had the biggest falloff in average hours worked.

Source: Mulligan, 2012.

Actually, the graph doesn’t quite show this story. We can see that high-middle skilled unmarried heads of households had an effective reduction in marginal earnings of more than 15 percent, yet they had the same or less reduction in hours than all but the highest skill group among married workers, all of whom had considerable smaller increases in effective marginal tax rates. If Mulligan has a case here, it rests on the lowest skill, low-middle skilled and middle skilled group among unmarried heads of households. (To convince yourself of this fact, cover up these three points and see if the graph tells you anything about the relationship between the drop in hours and the change in effective tax rates.)

There are a couple of points to be made about this analysis. First, we had around 10.5 million employed single heads of households in 2007. This means that we can’t hope to explain too large a share of the 10 million lost jobs in the downturn on this group. The second point is that once we begin to divide this group by skills the samples are not very large. We also run the risk that we are picking up other effects, most notably that these are likely to be younger workers who have had particularly bad employment experiences in the downturn.

But let’s accept Mulligan’s work at face value. Note that his endpoint is 2010. The reason is that benefits became notable less generous after 2010 by his calculations as many programs expired. Depending on the group, a quarter to one-third of the disincentive would have been eliminated. This means that we should expect to see a substantial uptick in hours worked for the most affected groups.

It would take a bit of work to reproduce Mulligan’s skill groups, but if we look at the less-skilled segment of the population, those without high school degrees and those with just high school degrees, it is difficult to see much evidence of a gain in employment since 2010 when the work disincentives were lessened. In other words, if these people didn’t respond to the reduction of disincentives when programs expired, it’s hard to believe that they were responding to the increased disincentive whent the programs were expanded.

Employment to Population Ratio of People without High School Degrees

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Employment to Population Ratio of People with High School Degrees

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In short, Mulligan has an interesting story, but the data don’t seem to fit.

Addendum: The graph for those without high school degrees was corrected at 10:30. Thanks Barry.

Second Addendum: Since I’m beating up on Mulligan here, I want to give him credit for being right in his previous post. That one took Paul Krugman to task for arguing that anyone who believed that the release of the new version of the iPhone would increase GDP was a Keynesian. Mulligan gave a solidly grounded explanation whereby the new iPhone could simply be seen as the fruit that came from prior years’ investment. Of course Krugman is right that what is going on is a Keynesian boost to demand, but he is wrong that there is no possible non-Keynesian explanation for the iPhone providing a boost to growth.

Casey Mulligan takes another stab at explaining the drop in employment since the housing market crash on changes in incentives in the NYT today. The basic story is that the extension of the length of unemployment insurance (UI), the easing of eligibility rules, the increased generosity of food stamps and several other changes in tax and benefit structures gave people less incentive to work. As a result, more people opted to rely on these benefits rather than work, hence the large falloff in employment and the rise in the unemployment rate.

There are many problems with this story, most importantly that people who have looked at what happens to workers whose UI benefits expire (e.g. Jesse Rothstein) find that most of them simply leave the labor force. They do not suddenly start working. Since the extension of UI benefits was by far the most important change in incentives since the start of the downturn, and we don’t see much evidence of an effect on employment, we might have some reason to believe that the other smaller changes had much effect.

But Mulligan presents us with a graph that shows that groups that saw larger increases in effective tax rates (which includes the loss of benefits from working as an implicit tax) had the biggest falloff in average hours worked.

Source: Mulligan, 2012.

Actually, the graph doesn’t quite show this story. We can see that high-middle skilled unmarried heads of households had an effective reduction in marginal earnings of more than 15 percent, yet they had the same or less reduction in hours than all but the highest skill group among married workers, all of whom had considerable smaller increases in effective marginal tax rates. If Mulligan has a case here, it rests on the lowest skill, low-middle skilled and middle skilled group among unmarried heads of households. (To convince yourself of this fact, cover up these three points and see if the graph tells you anything about the relationship between the drop in hours and the change in effective tax rates.)

There are a couple of points to be made about this analysis. First, we had around 10.5 million employed single heads of households in 2007. This means that we can’t hope to explain too large a share of the 10 million lost jobs in the downturn on this group. The second point is that once we begin to divide this group by skills the samples are not very large. We also run the risk that we are picking up other effects, most notably that these are likely to be younger workers who have had particularly bad employment experiences in the downturn.

But let’s accept Mulligan’s work at face value. Note that his endpoint is 2010. The reason is that benefits became notable less generous after 2010 by his calculations as many programs expired. Depending on the group, a quarter to one-third of the disincentive would have been eliminated. This means that we should expect to see a substantial uptick in hours worked for the most affected groups.

It would take a bit of work to reproduce Mulligan’s skill groups, but if we look at the less-skilled segment of the population, those without high school degrees and those with just high school degrees, it is difficult to see much evidence of a gain in employment since 2010 when the work disincentives were lessened. In other words, if these people didn’t respond to the reduction of disincentives when programs expired, it’s hard to believe that they were responding to the increased disincentive whent the programs were expanded.

Employment to Population Ratio of People without High School Degrees

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Employment to Population Ratio of People with High School Degrees

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In short, Mulligan has an interesting story, but the data don’t seem to fit.

Addendum: The graph for those without high school degrees was corrected at 10:30. Thanks Barry.

Second Addendum: Since I’m beating up on Mulligan here, I want to give him credit for being right in his previous post. That one took Paul Krugman to task for arguing that anyone who believed that the release of the new version of the iPhone would increase GDP was a Keynesian. Mulligan gave a solidly grounded explanation whereby the new iPhone could simply be seen as the fruit that came from prior years’ investment. Of course Krugman is right that what is going on is a Keynesian boost to demand, but he is wrong that there is no possible non-Keynesian explanation for the iPhone providing a boost to growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión