The NYT notes that the deficit is likely to surpass $1 trillion for the fourth consecutive year. It then tells readers:

“Against that headline-grabbing figure, Mr. Obama’s explanation — that the deficit he inherited is actually on a path to be cut in half just a year later than he promised, measured as a percentage of the economy’s total output — risks sounding professorial at best.”

Many people might have thought that newspapers control what goes into their headlines (the headline of this piece is “Obama faces test as deficit stays above $1 trillion). This should mean that they have the ability to write their headlines and articles in ways that best convey information to readers, not fan fears that are promoted by partisans of a particular course of action (i.e. deficit reduction). This means that if President Obama’s explanation for the deficit is valid (it is), then it is the responsibility of the paper to explain it to readers in a way that is understandable to them.

The piece notes projected increases in the ratio of debt to GDP. It then tells readers:

“Many analysts say that a nation’s debt should not exceed 60 percent to 70 percent.”

While it does not identify these analysts, they are obviously people who are ill-informed about budget accounting. If we are only concerned about the ratio of debt to GDP, then the Treasury will be able to buy back long-term debt issued today at very low interest rates at a substantial discount if interest rates rise back to more normal levels as predicted by the Congressional Budget Office and others.

A 30-year bond issued at a 2.75 percent interest rate, would sell at a 40 percent discount if the long-term interest rate rose to a more normal 6.0 percent. This means that if the Treasury had $4 trillion in 30-year bonds outstanding, it would be able to buy them back for 2.4 billion, instantly eliminating $1.6 trillion in debt or roughly 10 percentage points of GDP.

This would of course be silly, the interest burden would not have changed, but budget analysts who think that a nation’s debt should not exceed 60 percent to 70 percent would be made very happy by this action. In reality what matters is the ratio of interest payments to GDP, which is now near a post-World War II low. Remarkably, this fact is never mentioned in this piece.

The NYT notes that the deficit is likely to surpass $1 trillion for the fourth consecutive year. It then tells readers:

“Against that headline-grabbing figure, Mr. Obama’s explanation — that the deficit he inherited is actually on a path to be cut in half just a year later than he promised, measured as a percentage of the economy’s total output — risks sounding professorial at best.”

Many people might have thought that newspapers control what goes into their headlines (the headline of this piece is “Obama faces test as deficit stays above $1 trillion). This should mean that they have the ability to write their headlines and articles in ways that best convey information to readers, not fan fears that are promoted by partisans of a particular course of action (i.e. deficit reduction). This means that if President Obama’s explanation for the deficit is valid (it is), then it is the responsibility of the paper to explain it to readers in a way that is understandable to them.

The piece notes projected increases in the ratio of debt to GDP. It then tells readers:

“Many analysts say that a nation’s debt should not exceed 60 percent to 70 percent.”

While it does not identify these analysts, they are obviously people who are ill-informed about budget accounting. If we are only concerned about the ratio of debt to GDP, then the Treasury will be able to buy back long-term debt issued today at very low interest rates at a substantial discount if interest rates rise back to more normal levels as predicted by the Congressional Budget Office and others.

A 30-year bond issued at a 2.75 percent interest rate, would sell at a 40 percent discount if the long-term interest rate rose to a more normal 6.0 percent. This means that if the Treasury had $4 trillion in 30-year bonds outstanding, it would be able to buy them back for 2.4 billion, instantly eliminating $1.6 trillion in debt or roughly 10 percentage points of GDP.

This would of course be silly, the interest burden would not have changed, but budget analysts who think that a nation’s debt should not exceed 60 percent to 70 percent would be made very happy by this action. In reality what matters is the ratio of interest payments to GDP, which is now near a post-World War II low. Remarkably, this fact is never mentioned in this piece.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Casey Mulligan takes another stab at explaining the drop in employment since the housing market crash on changes in incentives in the NYT today. The basic story is that the extension of the length of unemployment insurance (UI), the easing of eligibility rules, the increased generosity of food stamps and several other changes in tax and benefit structures gave people less incentive to work. As a result, more people opted to rely on these benefits rather than work, hence the large falloff in employment and the rise in the unemployment rate.

There are many problems with this story, most importantly that people who have looked at what happens to workers whose UI benefits expire (e.g. Jesse Rothstein) find that most of them simply leave the labor force. They do not suddenly start working. Since the extension of UI benefits was by far the most important change in incentives since the start of the downturn, and we don’t see much evidence of an effect on employment, we might have some reason to believe that the other smaller changes had much effect.

But Mulligan presents us with a graph that shows that groups that saw larger increases in effective tax rates (which includes the loss of benefits from working as an implicit tax) had the biggest falloff in average hours worked.

Source: Mulligan, 2012.

Actually, the graph doesn’t quite show this story. We can see that high-middle skilled unmarried heads of households had an effective reduction in marginal earnings of more than 15 percent, yet they had the same or less reduction in hours than all but the highest skill group among married workers, all of whom had considerable smaller increases in effective marginal tax rates. If Mulligan has a case here, it rests on the lowest skill, low-middle skilled and middle skilled group among unmarried heads of households. (To convince yourself of this fact, cover up these three points and see if the graph tells you anything about the relationship between the drop in hours and the change in effective tax rates.)

There are a couple of points to be made about this analysis. First, we had around 10.5 million employed single heads of households in 2007. This means that we can’t hope to explain too large a share of the 10 million lost jobs in the downturn on this group. The second point is that once we begin to divide this group by skills the samples are not very large. We also run the risk that we are picking up other effects, most notably that these are likely to be younger workers who have had particularly bad employment experiences in the downturn.

But let’s accept Mulligan’s work at face value. Note that his endpoint is 2010. The reason is that benefits became notable less generous after 2010 by his calculations as many programs expired. Depending on the group, a quarter to one-third of the disincentive would have been eliminated. This means that we should expect to see a substantial uptick in hours worked for the most affected groups.

It would take a bit of work to reproduce Mulligan’s skill groups, but if we look at the less-skilled segment of the population, those without high school degrees and those with just high school degrees, it is difficult to see much evidence of a gain in employment since 2010 when the work disincentives were lessened. In other words, if these people didn’t respond to the reduction of disincentives when programs expired, it’s hard to believe that they were responding to the increased disincentive whent the programs were expanded.

Employment to Population Ratio of People without High School Degrees

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Employment to Population Ratio of People with High School Degrees

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In short, Mulligan has an interesting story, but the data don’t seem to fit.

Addendum: The graph for those without high school degrees was corrected at 10:30. Thanks Barry.

Second Addendum: Since I’m beating up on Mulligan here, I want to give him credit for being right in his previous post. That one took Paul Krugman to task for arguing that anyone who believed that the release of the new version of the iPhone would increase GDP was a Keynesian. Mulligan gave a solidly grounded explanation whereby the new iPhone could simply be seen as the fruit that came from prior years’ investment. Of course Krugman is right that what is going on is a Keynesian boost to demand, but he is wrong that there is no possible non-Keynesian explanation for the iPhone providing a boost to growth.

Casey Mulligan takes another stab at explaining the drop in employment since the housing market crash on changes in incentives in the NYT today. The basic story is that the extension of the length of unemployment insurance (UI), the easing of eligibility rules, the increased generosity of food stamps and several other changes in tax and benefit structures gave people less incentive to work. As a result, more people opted to rely on these benefits rather than work, hence the large falloff in employment and the rise in the unemployment rate.

There are many problems with this story, most importantly that people who have looked at what happens to workers whose UI benefits expire (e.g. Jesse Rothstein) find that most of them simply leave the labor force. They do not suddenly start working. Since the extension of UI benefits was by far the most important change in incentives since the start of the downturn, and we don’t see much evidence of an effect on employment, we might have some reason to believe that the other smaller changes had much effect.

But Mulligan presents us with a graph that shows that groups that saw larger increases in effective tax rates (which includes the loss of benefits from working as an implicit tax) had the biggest falloff in average hours worked.

Source: Mulligan, 2012.

Actually, the graph doesn’t quite show this story. We can see that high-middle skilled unmarried heads of households had an effective reduction in marginal earnings of more than 15 percent, yet they had the same or less reduction in hours than all but the highest skill group among married workers, all of whom had considerable smaller increases in effective marginal tax rates. If Mulligan has a case here, it rests on the lowest skill, low-middle skilled and middle skilled group among unmarried heads of households. (To convince yourself of this fact, cover up these three points and see if the graph tells you anything about the relationship between the drop in hours and the change in effective tax rates.)

There are a couple of points to be made about this analysis. First, we had around 10.5 million employed single heads of households in 2007. This means that we can’t hope to explain too large a share of the 10 million lost jobs in the downturn on this group. The second point is that once we begin to divide this group by skills the samples are not very large. We also run the risk that we are picking up other effects, most notably that these are likely to be younger workers who have had particularly bad employment experiences in the downturn.

But let’s accept Mulligan’s work at face value. Note that his endpoint is 2010. The reason is that benefits became notable less generous after 2010 by his calculations as many programs expired. Depending on the group, a quarter to one-third of the disincentive would have been eliminated. This means that we should expect to see a substantial uptick in hours worked for the most affected groups.

It would take a bit of work to reproduce Mulligan’s skill groups, but if we look at the less-skilled segment of the population, those without high school degrees and those with just high school degrees, it is difficult to see much evidence of a gain in employment since 2010 when the work disincentives were lessened. In other words, if these people didn’t respond to the reduction of disincentives when programs expired, it’s hard to believe that they were responding to the increased disincentive whent the programs were expanded.

Employment to Population Ratio of People without High School Degrees

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Employment to Population Ratio of People with High School Degrees

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In short, Mulligan has an interesting story, but the data don’t seem to fit.

Addendum: The graph for those without high school degrees was corrected at 10:30. Thanks Barry.

Second Addendum: Since I’m beating up on Mulligan here, I want to give him credit for being right in his previous post. That one took Paul Krugman to task for arguing that anyone who believed that the release of the new version of the iPhone would increase GDP was a Keynesian. Mulligan gave a solidly grounded explanation whereby the new iPhone could simply be seen as the fruit that came from prior years’ investment. Of course Krugman is right that what is going on is a Keynesian boost to demand, but he is wrong that there is no possible non-Keynesian explanation for the iPhone providing a boost to growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

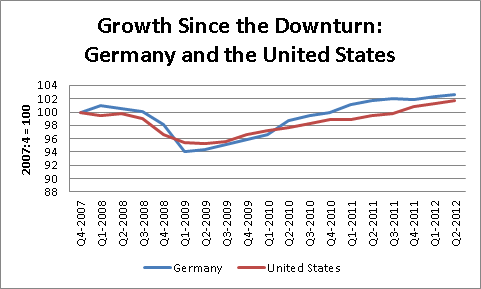

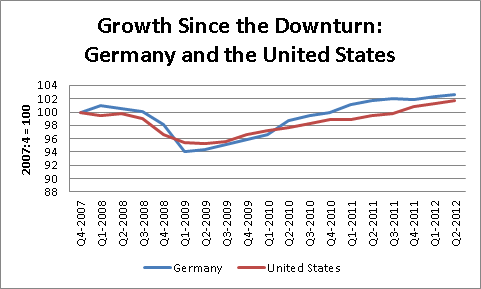

The NYT had an article that reported on Germany’s relative economic success and attributed it to the labor market reforms that reduced benefits for unemployed workers and took other steps to weaken workers’ bargaining power. While these reforms undoubtedly had the effect of reducing Germany’s labor costs and thereby allowing it to accumulate a large trade surplus in the euro zone (which meant that countries like Greece, Spain, and Ireland would have large trade deficits), this is only part of the story of Germany’s success in lowering its unemployment rate.

The fact that Germany has persuaded employers to reduce work hours rather than lay off workers has been at least as important in bringing down Germany’s unemployment rate. Germany’s growth rate since the downturn began has been almost identical to the growth rate in the United States. While the unemployment rate in the United States has risen by 3.6 percentage points over this period, from 4.5 percent to 8.1 percent, the unemployment rate in Germany has fallen by more than 2.0 percentage points from the 7.6 percent to 5.5 percent. It would have been worth noting the policy of promoting work sharing in this discussion.

Source: OECD.

Source: OECD.

The NYT article also wrongly refers to the official Germany unemployment rate of 7.0 percent instead of the OECD harmonized rate. The official German rate counts people who are working part-time but desire full-time employment as being unemployed. It therefore is not directly comparable to the U.S. unemployment rate. The OECD harmonized unemployment rate uses the same methodology as the U.S. Labor Department.

The NYT had an article that reported on Germany’s relative economic success and attributed it to the labor market reforms that reduced benefits for unemployed workers and took other steps to weaken workers’ bargaining power. While these reforms undoubtedly had the effect of reducing Germany’s labor costs and thereby allowing it to accumulate a large trade surplus in the euro zone (which meant that countries like Greece, Spain, and Ireland would have large trade deficits), this is only part of the story of Germany’s success in lowering its unemployment rate.

The fact that Germany has persuaded employers to reduce work hours rather than lay off workers has been at least as important in bringing down Germany’s unemployment rate. Germany’s growth rate since the downturn began has been almost identical to the growth rate in the United States. While the unemployment rate in the United States has risen by 3.6 percentage points over this period, from 4.5 percent to 8.1 percent, the unemployment rate in Germany has fallen by more than 2.0 percentage points from the 7.6 percent to 5.5 percent. It would have been worth noting the policy of promoting work sharing in this discussion.

Source: OECD.

Source: OECD.

The NYT article also wrongly refers to the official Germany unemployment rate of 7.0 percent instead of the OECD harmonized rate. The official German rate counts people who are working part-time but desire full-time employment as being unemployed. It therefore is not directly comparable to the U.S. unemployment rate. The OECD harmonized unemployment rate uses the same methodology as the U.S. Labor Department.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what Brad Plumer tells us. As we like to say here at BTP, if everyone in Washington agrees, it’s got to be wrong.

That’s what Brad Plumer tells us. As we like to say here at BTP, if everyone in Washington agrees, it’s got to be wrong.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I really don’t want to waste my time talking about Governor Romney’s tax returns, but come on folks. He was asked on 60 Minutes about whether it was fair that he paid a 14 percent tax rate on his income, compared to the much higher tax rate paid by many middle income families. According to the Huffington Post’s account, he responded by saying:

“It is a low rate, … And one of the reasons why the capital gains tax rate is lower is because capital has already been taxed once at the corporate level, as high as 35 percent.”

If the question is why does Mitt Romney pay a low tax rate, this answer is wrong. The bulk of his income comes from Bain Capital. Bain Capital is organized as a partnership. This means that income is not taxed at the corporate level. It is only taxed when partners like Mitt Romney receive it. So the story of double taxation simply does not fly in Romney’s own case.

For those who are making a sport of dissecting the Romney tax returns, this is a really big one to let slide through the cracks. Other folks who get dividends or capital gains from owning shares of stock can tell the double taxation story (even here it doesn’t really fit; they got the benefits of corporate status in exchange for the corporate taxes), but in Romney’s case this justification doesn’t pass the laugh test.

I really don’t want to waste my time talking about Governor Romney’s tax returns, but come on folks. He was asked on 60 Minutes about whether it was fair that he paid a 14 percent tax rate on his income, compared to the much higher tax rate paid by many middle income families. According to the Huffington Post’s account, he responded by saying:

“It is a low rate, … And one of the reasons why the capital gains tax rate is lower is because capital has already been taxed once at the corporate level, as high as 35 percent.”

If the question is why does Mitt Romney pay a low tax rate, this answer is wrong. The bulk of his income comes from Bain Capital. Bain Capital is organized as a partnership. This means that income is not taxed at the corporate level. It is only taxed when partners like Mitt Romney receive it. So the story of double taxation simply does not fly in Romney’s own case.

For those who are making a sport of dissecting the Romney tax returns, this is a really big one to let slide through the cracks. Other folks who get dividends or capital gains from owning shares of stock can tell the double taxation story (even here it doesn’t really fit; they got the benefits of corporate status in exchange for the corporate taxes), but in Romney’s case this justification doesn’t pass the laugh test.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

People are used to strange statements on the economy in the Washington Post, hence we have Charles Lane’s column complaining about the Fed’s “trickle down” economics. Lane somehow has the idea that the main way in which the Fed expects its latest commitment to low interest rates and quantitative easing to create jobs is by raising stock prices. He would know better even if he just read the Post’s business section.

The main ways in which the action is supposed to boost demand is by reducing mortgage interest rates, increasing inflationary expectations and lowering the value of the dollar. A higher stock market would be at best fourth on this list. Taking each of these briefly in turn, lower mortgage interest rates improve the situation of those who now hold a mortgage or will be able to buy a house relative to those who lend. The former group admittedly does not include the poorest of the poor, but on average it certainly has a lower income and less wealth than the latter group.

In the case of higher inflationary expectations, the idea is that firms will expect that they will be able to sell their goods at higher prices, therefore they will be more willing to invest than would otherwise be the case. This generates more employment, again a plus for the middle and bottom. Furthermore, if the inflation actually does take place, the value of debt on homes, cars, credit cards and mortgages is reduced; another plus for those lower down the income ladder.

In the case of a lower valued dollar, the effect will be to increase employment in U.S. manufacturing and other sectors open to trade. This will increase the wages of these workers relative to the wages of workers in protected sectors, like doctors and lawyers. Again, this is a plus for those lower down the income ladder.

Lane has some bizarre stories to get the opposite conclusions. Most importantly he has the Fed action increasing the price of oil, food and other commodities. This one doesn’t fit the data (in most cases commodities prices have not come close to their 2008 pre-quantitative easing peaks), but more importantly it doesn’t make any sense. There is always speculation in commodities (in both directions) and it is cheaper to speculate when interest rates are lower, but how do we get a sustained increase in prices from the Fed’s policies. Will quantitative easing lead to a lasting reduction in the world supply of any commodity? Alternatively, will it cause a sustained increase in demand beyond what we would have gotten from growth in any case?

It is difficult to see how the answer to either of these questions can be yes. If both answers are no, then at worst the Fed policy would lead to a short-term uptick in prices, which will be followed by a period of lower than normal prices after the speculative bubble bursts and the excess supply floods the market. The volatility is not a good thing (financial speculation taxes anyone?), but it does not imply a sustained reduction in the living standards of the poor or middle class. (Lane also misrepresents the impact on the poor by taking their spending on food and gas as a share of their income. Serious people would take it as a share of total expenditures. It gives a very different and more realistic story.)

Lane concludes by mixing in a criticism of the Fed’s rescue of too big to fail banks with his complaint about the Fed’s latest policy move. High levels of employment unambiguously redistribute income toward the bottom and middle. Insofar as the Fed’s actions go this way, they deserve praise. Keeping too big to fail banks going is certainly bad policy, but it is difficult to see the connection to the Fed’s latest move.

People are used to strange statements on the economy in the Washington Post, hence we have Charles Lane’s column complaining about the Fed’s “trickle down” economics. Lane somehow has the idea that the main way in which the Fed expects its latest commitment to low interest rates and quantitative easing to create jobs is by raising stock prices. He would know better even if he just read the Post’s business section.

The main ways in which the action is supposed to boost demand is by reducing mortgage interest rates, increasing inflationary expectations and lowering the value of the dollar. A higher stock market would be at best fourth on this list. Taking each of these briefly in turn, lower mortgage interest rates improve the situation of those who now hold a mortgage or will be able to buy a house relative to those who lend. The former group admittedly does not include the poorest of the poor, but on average it certainly has a lower income and less wealth than the latter group.

In the case of higher inflationary expectations, the idea is that firms will expect that they will be able to sell their goods at higher prices, therefore they will be more willing to invest than would otherwise be the case. This generates more employment, again a plus for the middle and bottom. Furthermore, if the inflation actually does take place, the value of debt on homes, cars, credit cards and mortgages is reduced; another plus for those lower down the income ladder.

In the case of a lower valued dollar, the effect will be to increase employment in U.S. manufacturing and other sectors open to trade. This will increase the wages of these workers relative to the wages of workers in protected sectors, like doctors and lawyers. Again, this is a plus for those lower down the income ladder.

Lane has some bizarre stories to get the opposite conclusions. Most importantly he has the Fed action increasing the price of oil, food and other commodities. This one doesn’t fit the data (in most cases commodities prices have not come close to their 2008 pre-quantitative easing peaks), but more importantly it doesn’t make any sense. There is always speculation in commodities (in both directions) and it is cheaper to speculate when interest rates are lower, but how do we get a sustained increase in prices from the Fed’s policies. Will quantitative easing lead to a lasting reduction in the world supply of any commodity? Alternatively, will it cause a sustained increase in demand beyond what we would have gotten from growth in any case?

It is difficult to see how the answer to either of these questions can be yes. If both answers are no, then at worst the Fed policy would lead to a short-term uptick in prices, which will be followed by a period of lower than normal prices after the speculative bubble bursts and the excess supply floods the market. The volatility is not a good thing (financial speculation taxes anyone?), but it does not imply a sustained reduction in the living standards of the poor or middle class. (Lane also misrepresents the impact on the poor by taking their spending on food and gas as a share of their income. Serious people would take it as a share of total expenditures. It gives a very different and more realistic story.)

Lane concludes by mixing in a criticism of the Fed’s rescue of too big to fail banks with his complaint about the Fed’s latest policy move. High levels of employment unambiguously redistribute income toward the bottom and middle. Insofar as the Fed’s actions go this way, they deserve praise. Keeping too big to fail banks going is certainly bad policy, but it is difficult to see the connection to the Fed’s latest move.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post has a piece on how Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke transformed the Fed so that it now has an active role in boosting the economy. In fact it is difficult to see anything qualitatively different about the role that Bernanke has set for the Fed. As the piece notes, high employment is part of its mandate. In past recessions, the Fed has sharply reduced the federal funds rate to help boost the economy.

As can be seen, the Fed lowered the federal funds rate from 19 percent to 8 percent to boost the economy following the 1981-82 recession. It dropped the rate from 12.5 percent to 5.0 percent following the 1974-75 recession. The difference in this case is that the downturn is more severe and with inflation very low, the Fed has hit the limit of what it can do by lowering the federal funds rate since it is already zero. This has forced it to pursue extraordinary measures like quantitative easing and long-term commitments to keeping interest rates low. It is more the conditions which have changed rather than the Fed’s role in the economy.

This piece also includes a line about the risks of the Fed’s expansionary policy:

“The most significant [risk] is that the Fed’s efforts heat up economic growth in a way that unleashes inflation, which would eat away at middle-class incomes.”

Actually it is very difficult to imagine inflation taking a form that would “eat away at middle-class incomes.” If the economy heats up in the way described, it means that unemployment would fall sharply, leading to more rapid wage growth. This rapid wage growth would be the factor driving inflation. Since most middle income people get most of their income from wages, if wages are rising rapidly, it is unlikely that their income would be eroding. Most middle income retirees get most of their income from Social Security which is indexed to inflation, so these people would be largely protected as well.

The big losers from higher than expected inflation would be lenders, like the Wall Street banks, who have large amounts of loans outstanding that would suddenly be worth much less in a higher inflation environment. This is a reason why Wall Street is generally a forceful lobby against higher inflation.

At one point the piece refers to Bernanke’s “grueling” years at the Fed. It is worth pointing out that the main reason the years have been grueling is that Bernanke and Greenspan failed to recognize the housing bubble (Bernanke was a Fed governor from 2002 to 2005) and to take steps to deflate it before it grew large enough to do so much damage to the economy. In other words, he is cleaning up his own mess.

The Washington Post has a piece on how Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke transformed the Fed so that it now has an active role in boosting the economy. In fact it is difficult to see anything qualitatively different about the role that Bernanke has set for the Fed. As the piece notes, high employment is part of its mandate. In past recessions, the Fed has sharply reduced the federal funds rate to help boost the economy.

As can be seen, the Fed lowered the federal funds rate from 19 percent to 8 percent to boost the economy following the 1981-82 recession. It dropped the rate from 12.5 percent to 5.0 percent following the 1974-75 recession. The difference in this case is that the downturn is more severe and with inflation very low, the Fed has hit the limit of what it can do by lowering the federal funds rate since it is already zero. This has forced it to pursue extraordinary measures like quantitative easing and long-term commitments to keeping interest rates low. It is more the conditions which have changed rather than the Fed’s role in the economy.

This piece also includes a line about the risks of the Fed’s expansionary policy:

“The most significant [risk] is that the Fed’s efforts heat up economic growth in a way that unleashes inflation, which would eat away at middle-class incomes.”

Actually it is very difficult to imagine inflation taking a form that would “eat away at middle-class incomes.” If the economy heats up in the way described, it means that unemployment would fall sharply, leading to more rapid wage growth. This rapid wage growth would be the factor driving inflation. Since most middle income people get most of their income from wages, if wages are rising rapidly, it is unlikely that their income would be eroding. Most middle income retirees get most of their income from Social Security which is indexed to inflation, so these people would be largely protected as well.

The big losers from higher than expected inflation would be lenders, like the Wall Street banks, who have large amounts of loans outstanding that would suddenly be worth much less in a higher inflation environment. This is a reason why Wall Street is generally a forceful lobby against higher inflation.

At one point the piece refers to Bernanke’s “grueling” years at the Fed. It is worth pointing out that the main reason the years have been grueling is that Bernanke and Greenspan failed to recognize the housing bubble (Bernanke was a Fed governor from 2002 to 2005) and to take steps to deflate it before it grew large enough to do so much damage to the economy. In other words, he is cleaning up his own mess.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

His piece today notes that many people who start college don’t finish and that many people got themselves into bad mortgages that they could not afford in the housing bubble years. He therefore concludes that government really cannot do much to ensure low income people a path to the middle class:

“What also cannot be wished away are on-the-ground realities that impede middle-class status for more Americans. Only one-third of children born to the poorest fifth of Americans graduate high school with at least a 2.5 grade-point average and without having become a parent or been convicted of a crime, reports a Brookings Institution study. Brookings economist Isabel Sawhill notes that gaps have widened between the children of poor and well-to-do families on school test scores, college attendance and family formation. In his book “Coming Apart,” conservative scholar Charles Murray makes similar points.

Government has only limited power to offset these disadvantages. The appeal of the American Dream is that it’s disconnected from nasty facts and choices.”

Of course many of the realities on the ground reflect deliberate government policy to redistribute income upward. In the last three decades the government has done everything possible to remove barriers that obstruct manufactured goods from entering the United States. This policy coupled with the over-valued dollar threw millions of manufacturing workers out of work and put downward pressure on the wages of less-educated workers. Instead the government could have pursued a “free trade” policy that focused on reducing the barriers that prevented foreign professionals (e.g. doctors, lawyers, economists) from training to U.S. standards and working in the United States. This would have had the effect of driving down the wages of U.S. professionals. That would reduce the cost of health care, legal services, university education and many other items, thereby raising real wages and producing large economic gains.

The government could have eliminated the special low tax status that the financial industry enjoys, thereby allowing it to grow as parasite on the rest of the economy. It is also the source of many of the highest incomes in the country.

And, the government need not have strengthened patent and copyright protection. These monopolies redistribute several hundred billion dollars a year from consumers to drug companies, software companies and the entertainment industry. (Yes, this upward redistribution is the topic of my book, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.)

In short the government could have done a lot to improve the plight of lower income people just by not pursuing the policies that have worsened their plight. Of course it could have also raised the minimum wage in step with productivity growth, as it had done in the quarter century following World War II. If this had been the policy, the minimum wage would be close to $18 an hour today. That might make a difference to the middle class aspirations of many workers.

His piece today notes that many people who start college don’t finish and that many people got themselves into bad mortgages that they could not afford in the housing bubble years. He therefore concludes that government really cannot do much to ensure low income people a path to the middle class:

“What also cannot be wished away are on-the-ground realities that impede middle-class status for more Americans. Only one-third of children born to the poorest fifth of Americans graduate high school with at least a 2.5 grade-point average and without having become a parent or been convicted of a crime, reports a Brookings Institution study. Brookings economist Isabel Sawhill notes that gaps have widened between the children of poor and well-to-do families on school test scores, college attendance and family formation. In his book “Coming Apart,” conservative scholar Charles Murray makes similar points.

Government has only limited power to offset these disadvantages. The appeal of the American Dream is that it’s disconnected from nasty facts and choices.”

Of course many of the realities on the ground reflect deliberate government policy to redistribute income upward. In the last three decades the government has done everything possible to remove barriers that obstruct manufactured goods from entering the United States. This policy coupled with the over-valued dollar threw millions of manufacturing workers out of work and put downward pressure on the wages of less-educated workers. Instead the government could have pursued a “free trade” policy that focused on reducing the barriers that prevented foreign professionals (e.g. doctors, lawyers, economists) from training to U.S. standards and working in the United States. This would have had the effect of driving down the wages of U.S. professionals. That would reduce the cost of health care, legal services, university education and many other items, thereby raising real wages and producing large economic gains.

The government could have eliminated the special low tax status that the financial industry enjoys, thereby allowing it to grow as parasite on the rest of the economy. It is also the source of many of the highest incomes in the country.

And, the government need not have strengthened patent and copyright protection. These monopolies redistribute several hundred billion dollars a year from consumers to drug companies, software companies and the entertainment industry. (Yes, this upward redistribution is the topic of my book, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.)

In short the government could have done a lot to improve the plight of lower income people just by not pursuing the policies that have worsened their plight. Of course it could have also raised the minimum wage in step with productivity growth, as it had done in the quarter century following World War II. If this had been the policy, the minimum wage would be close to $18 an hour today. That might make a difference to the middle class aspirations of many workers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Any time you hear anyone tell you that “all economists agree,” get out your gun. Unless the question pertains to the shape of the earth, this is almost certainly not true.

It is most definitely not the case that economists agree that Mitt Romney should be paying his current 14.1 percent tax rate or less as Washington Post readers were told by Dylan Matthews today. Matthews rests his case on some arguments in the literature concerning scenarios in which we both look to an infinite future horizon and we have identically situated individuals, meaning that we all have the same wealth and the same opportunity to gain income. When these assumptions are relaxed, the case for preferential treatment of capital income becomes considerably weaker, as argued in a recent Journal of Economic Perspectives article by Peter Diamond and Emmanuel Saez, two of the most prominent public finance economists in the world.

The second point here is probably the more important. If we have some individuals who inherit immense wealth so that they can live entirely off their capital income and other individuals who must work for their income, a policy that subjects capital income tax to a lower rate of taxation than labor income means that we are taxing the rich at a lower rate than the middle class and poor. It is difficult to see how this is either efficient (we are giving disincentives to work for middle class people as a result of a higher than necessary tax rate) or fair.

Furthermore, as a result of having a lower tax rate on capital income than labor income we are giving people an incentive to game the tax code by concealing labor income as capital income. While most workers may not have much opportunity to play such games, higher end workers, such as doctors or lawyers with their own practices would have ample opportunities for such gaming. This is both unfair and leads to a waste of resources as these people employ accountants to rig their books.

In fact, Mitt Romney and his firm Bain Capital were experts at such gaming. They routinely negotiated deals that changed management fees, which would be taxed as normal income, into carried interest which would be taxed at the capital gains tax rate. Few, if any, economists would agree that allowing for such deals is good policy.

Finally, even if economists might in general agree that it makes sense to have a lower tax rate on capital income than labor income, it does not at all follow that they think that Mitt Romney was paying enough in taxes. The article by Diamond and Saez suggests a top marginal tax rate of around 70 percent. In this case, a 50 percent tax rate on capital gains would still provide a substantial benefit to earners of income from capital. That rate would be more than three times the tax rate that Mitt Romney paid on his income.

So when you get your score card out remember to put down that many, perhaps most, economists believe that Mitt Romney should pay more money in taxes. Don’t let the Washington Post fool you.

Any time you hear anyone tell you that “all economists agree,” get out your gun. Unless the question pertains to the shape of the earth, this is almost certainly not true.

It is most definitely not the case that economists agree that Mitt Romney should be paying his current 14.1 percent tax rate or less as Washington Post readers were told by Dylan Matthews today. Matthews rests his case on some arguments in the literature concerning scenarios in which we both look to an infinite future horizon and we have identically situated individuals, meaning that we all have the same wealth and the same opportunity to gain income. When these assumptions are relaxed, the case for preferential treatment of capital income becomes considerably weaker, as argued in a recent Journal of Economic Perspectives article by Peter Diamond and Emmanuel Saez, two of the most prominent public finance economists in the world.

The second point here is probably the more important. If we have some individuals who inherit immense wealth so that they can live entirely off their capital income and other individuals who must work for their income, a policy that subjects capital income tax to a lower rate of taxation than labor income means that we are taxing the rich at a lower rate than the middle class and poor. It is difficult to see how this is either efficient (we are giving disincentives to work for middle class people as a result of a higher than necessary tax rate) or fair.

Furthermore, as a result of having a lower tax rate on capital income than labor income we are giving people an incentive to game the tax code by concealing labor income as capital income. While most workers may not have much opportunity to play such games, higher end workers, such as doctors or lawyers with their own practices would have ample opportunities for such gaming. This is both unfair and leads to a waste of resources as these people employ accountants to rig their books.

In fact, Mitt Romney and his firm Bain Capital were experts at such gaming. They routinely negotiated deals that changed management fees, which would be taxed as normal income, into carried interest which would be taxed at the capital gains tax rate. Few, if any, economists would agree that allowing for such deals is good policy.

Finally, even if economists might in general agree that it makes sense to have a lower tax rate on capital income than labor income, it does not at all follow that they think that Mitt Romney was paying enough in taxes. The article by Diamond and Saez suggests a top marginal tax rate of around 70 percent. In this case, a 50 percent tax rate on capital gains would still provide a substantial benefit to earners of income from capital. That rate would be more than three times the tax rate that Mitt Romney paid on his income.

So when you get your score card out remember to put down that many, perhaps most, economists believe that Mitt Romney should pay more money in taxes. Don’t let the Washington Post fool you.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Douthat’s column today lashes out at the economy of the Washington metropolitan area. Douthat describes it as an economy of exploitation as highly paid lobbyists thrive on efforts to manipulate government policy to advance their interests. Douthat is 100 percent on the mark here. This is a town chock full of 6 and 7-figure buffoons. People who draw paychecks in the hundreds of thousands or even millions but who have no discernible skills other than an impressive contact list.

What he gets wrong is tying this to government spending or the deficit. Many of the most important issues that lobbyists devote themselves to, such as patent and copyright rules, trade agreements (e.g. the Trans-Pacific Partnership), and rules on bank regulation, involve little or no government spending. However the sums of money are often far larger. For example, patent protection on prescription drugs will be worth more than $3.5 trillion to the pharmaceutical industry over the next decade.

Douthat is also wrong as to the reason we have a budget deficit. We have a budget deficit because the collapse of the housing bubble sank the economy. Most people in Washington didn’t see the bubble when it was expanding and apparently still haven’t noticed it even after it burst and wrecked the economy. The collapse of the bubble cost the economy $1.2-$1.5 trillion in annual demand. The deficit is helping to fill the gap created by the loss of private sector demand. This is primarily due to the fall in tax collections and the increase in payments like unemployment benefits and food stamps that automatically take place in a downturn.

Douthat’s column today lashes out at the economy of the Washington metropolitan area. Douthat describes it as an economy of exploitation as highly paid lobbyists thrive on efforts to manipulate government policy to advance their interests. Douthat is 100 percent on the mark here. This is a town chock full of 6 and 7-figure buffoons. People who draw paychecks in the hundreds of thousands or even millions but who have no discernible skills other than an impressive contact list.

What he gets wrong is tying this to government spending or the deficit. Many of the most important issues that lobbyists devote themselves to, such as patent and copyright rules, trade agreements (e.g. the Trans-Pacific Partnership), and rules on bank regulation, involve little or no government spending. However the sums of money are often far larger. For example, patent protection on prescription drugs will be worth more than $3.5 trillion to the pharmaceutical industry over the next decade.

Douthat is also wrong as to the reason we have a budget deficit. We have a budget deficit because the collapse of the housing bubble sank the economy. Most people in Washington didn’t see the bubble when it was expanding and apparently still haven’t noticed it even after it burst and wrecked the economy. The collapse of the bubble cost the economy $1.2-$1.5 trillion in annual demand. The deficit is helping to fill the gap created by the loss of private sector demand. This is primarily due to the fall in tax collections and the increase in payments like unemployment benefits and food stamps that automatically take place in a downturn.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión