The NYT has an article on how companies in the developing world have increased production of coolants that contribute to global warming in order to get credits for destroying them. This is the outcome of some of the perverse incentives created by the Clean Development Mechanism in the Kyoto agreement.

This sort of gaming was predictable and predicted at the time. The basic problem was that there was no well-developed baseline against which to assign credits to ensure that money was only paid in situations where it actually led to emissions reductions.

The article included a comment from David Doniger, a member of the “who could have known crowd” who is cited as an expert:

“‘I was a climate negotiator, and no one had this in mind,’ said David Doniger of the Natural Resources Defense Council. ‘It turns out you get nearly 100 times more from credits than it costs to do it. It turned the economics of the business on its head.'”

It would have been worth mentioning that Doniger is wrong, people did have this in mind. It was just the case that the people in positions of authority, and who were cited as experts on the topic, apparently did not understand that this sort of gaming would inevitably result from the deal they crafted.

The NYT has an article on how companies in the developing world have increased production of coolants that contribute to global warming in order to get credits for destroying them. This is the outcome of some of the perverse incentives created by the Clean Development Mechanism in the Kyoto agreement.

This sort of gaming was predictable and predicted at the time. The basic problem was that there was no well-developed baseline against which to assign credits to ensure that money was only paid in situations where it actually led to emissions reductions.

The article included a comment from David Doniger, a member of the “who could have known crowd” who is cited as an expert:

“‘I was a climate negotiator, and no one had this in mind,’ said David Doniger of the Natural Resources Defense Council. ‘It turns out you get nearly 100 times more from credits than it costs to do it. It turned the economics of the business on its head.'”

It would have been worth mentioning that Doniger is wrong, people did have this in mind. It was just the case that the people in positions of authority, and who were cited as experts on the topic, apparently did not understand that this sort of gaming would inevitably result from the deal they crafted.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT article noted new evidence of economic weakness in Germany and Italy then told readers:

“flagging growth is complicating European leaders’ quest to restore confidence in the euro zone.”

Of course one of the main reasons that growth in Europe is weak is the austerity measures that have been imposed across Europe. The loss of demand from the government means that there is less demand in the economy and therefore less growth. Apparently those in leadership positions believe that the confidence fairy will make up for the loss demand from the public sector, but unfortunate for workers living in Europe, the confidence fairy does not exist.

A NYT article noted new evidence of economic weakness in Germany and Italy then told readers:

“flagging growth is complicating European leaders’ quest to restore confidence in the euro zone.”

Of course one of the main reasons that growth in Europe is weak is the austerity measures that have been imposed across Europe. The loss of demand from the government means that there is less demand in the economy and therefore less growth. Apparently those in leadership positions believe that the confidence fairy will make up for the loss demand from the public sector, but unfortunate for workers living in Europe, the confidence fairy does not exist.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

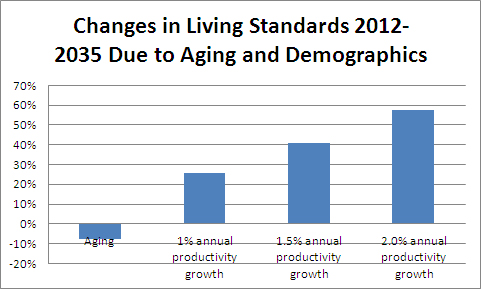

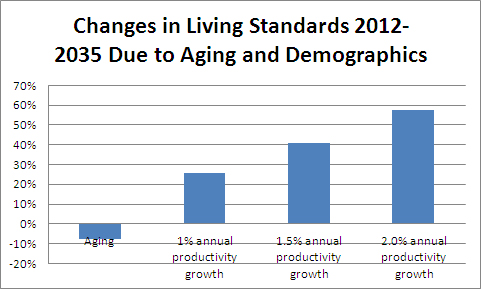

Ding, ding, ding! Robert Samuelson has just written the 1 millionth piece to appear in the Washington Post claiming that an aging population will undermine our children’s prosperity. He gets awarded a miniature golden baseball bat to symbolize his and the newspapers decades of bashing the elderly and trying to take away their Social Security and Medicare.

Arithmetic fans know that if our children and grandchildren live worse than we do it will be because the folks at the top grabbed away all the money. In any plausible scenario the gains from productivity growth will swamp any additional burdens placed on workers from a larger population of retirees.

The projections that Samuelson cites to make his point in fact demonstrate the opposite. He told readers:

“The ratio of workers to retirees, 5-to-1 in 1960 and 3-to-1 in 2010, is projected at nearly 2-to-1 by 2025.”

Yep, we have had a sharp decline in the ratio of workers to retirees from 1960 to 2010 (most of it by 1990) and yet average living standards rose substantially. This means that there is no reason that average living standards won’t continue to rise in the next several decades as the ratio of workers to retirees falls further.

The simple chart below compares the impact of the projected change in the ratio of workers to retirees on the living standards of workers assuming that an average retiree has 75 percent of the living standard of an average worker. It compares scenarios of 1.0 percent, 1.5 percent and 2.0 percent productivity growth.

Source: Author’s calculation, see text.

As can be seen, the impact of higher productivity growth in raising living standards swamps the impact of demographic change in lowering living standards. It is also important to note that the negative demographic shift ends in 2035. After that point the demographics stabilize or even improve slightly, which means that all future gains in productivity will go into the pockets of our children and grandchildren.

Of course BTP fans everywhere are jumping and down yelling that ordinary workers have not been seeing the gains of productivity growth. Real wages have been nearly stagnant for the last three decades. This is of course right, but that is exactly the point.

If our children and grandchildren do not enjoy substantially higher living standards than we do today, it will not be because they are paying for their parents or grandparents’ Social Security. It will be because the one percent have rigged the economic system so that most of the gains from growth go to the top.

The answer here is not cutting Social Security and Medicare, it is ending too big to fail insurance for huge banks and otherwise cutting a bloated financial system down to size. It is about ending trade and monetary policies that are decided to benefit the rich at the expense of the rest of us. It is about curtailing patent monopolies that has us spending $300 billion a year on drugs that would sell for $30 billion in a competitive market. And it is about fixing a corporate governance system where boards of directors are given 6-figure payoffs to look the other way as top management pillages the company. (See The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.)

In other words, the real story is not about inter-generational equality, no matter how many times the Post repeats this line. The real story is about intra-generational inequality.

Ding, ding, ding! Robert Samuelson has just written the 1 millionth piece to appear in the Washington Post claiming that an aging population will undermine our children’s prosperity. He gets awarded a miniature golden baseball bat to symbolize his and the newspapers decades of bashing the elderly and trying to take away their Social Security and Medicare.

Arithmetic fans know that if our children and grandchildren live worse than we do it will be because the folks at the top grabbed away all the money. In any plausible scenario the gains from productivity growth will swamp any additional burdens placed on workers from a larger population of retirees.

The projections that Samuelson cites to make his point in fact demonstrate the opposite. He told readers:

“The ratio of workers to retirees, 5-to-1 in 1960 and 3-to-1 in 2010, is projected at nearly 2-to-1 by 2025.”

Yep, we have had a sharp decline in the ratio of workers to retirees from 1960 to 2010 (most of it by 1990) and yet average living standards rose substantially. This means that there is no reason that average living standards won’t continue to rise in the next several decades as the ratio of workers to retirees falls further.

The simple chart below compares the impact of the projected change in the ratio of workers to retirees on the living standards of workers assuming that an average retiree has 75 percent of the living standard of an average worker. It compares scenarios of 1.0 percent, 1.5 percent and 2.0 percent productivity growth.

Source: Author’s calculation, see text.

As can be seen, the impact of higher productivity growth in raising living standards swamps the impact of demographic change in lowering living standards. It is also important to note that the negative demographic shift ends in 2035. After that point the demographics stabilize or even improve slightly, which means that all future gains in productivity will go into the pockets of our children and grandchildren.

Of course BTP fans everywhere are jumping and down yelling that ordinary workers have not been seeing the gains of productivity growth. Real wages have been nearly stagnant for the last three decades. This is of course right, but that is exactly the point.

If our children and grandchildren do not enjoy substantially higher living standards than we do today, it will not be because they are paying for their parents or grandparents’ Social Security. It will be because the one percent have rigged the economic system so that most of the gains from growth go to the top.

The answer here is not cutting Social Security and Medicare, it is ending too big to fail insurance for huge banks and otherwise cutting a bloated financial system down to size. It is about ending trade and monetary policies that are decided to benefit the rich at the expense of the rest of us. It is about curtailing patent monopolies that has us spending $300 billion a year on drugs that would sell for $30 billion in a competitive market. And it is about fixing a corporate governance system where boards of directors are given 6-figure payoffs to look the other way as top management pillages the company. (See The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.)

In other words, the real story is not about inter-generational equality, no matter how many times the Post repeats this line. The real story is about intra-generational inequality.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

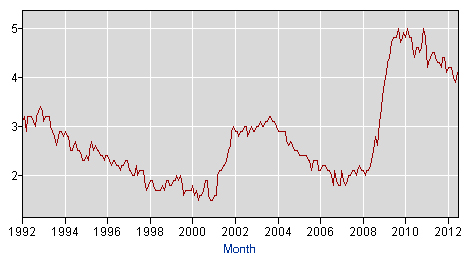

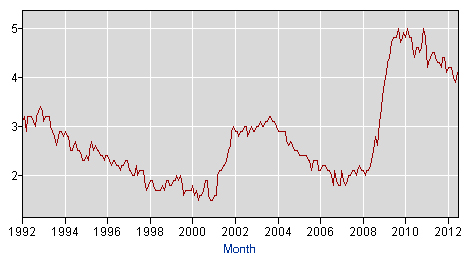

Jeffrey Sachs has played a useful role in challenging the economic orthodoxy in many areas over the last three years. However, when he tries to tell us that the current downturn is structural not cyclical he is way over his head in the quicksand of the orthodoxy.

Let’s start with his simple bold assertion:

“Consider the new U.S. unemployment announcement. If you are a college graduate, there is no employment crisis. 72.7 percent of the college-educated population age-25 and over is working. The unemployment rate is 4.1 percent. Incomes are good.”

Umm, no, that’s not right. If we go back to 2007 we would see that the unemployment rate for college grads was 1.9 percent at its low that year, less than half of the current rate. It averaged 1.6 percent in 2000.

Unemployment Rate for College Grads, 25 years and Over

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

If the current unemployment in the U.S. economy were structural than we should expect to see lower than normal for these college grads whose labor is in short supply. Instead, we see that their unemployment rate is more than twice the pre-recession level and close two and half times its 2000 level.

We should also expect to see that real wages for college grads are rising rapidly. They aren’t. They have not even kept pace with inflation for the last dozen years.

In short, Sachs does not even have the beginning of an argument here. He’d better find some new data or give up his argument that the causes of unemployment are structural. His data indicate the opposite.

Jeffrey Sachs has played a useful role in challenging the economic orthodoxy in many areas over the last three years. However, when he tries to tell us that the current downturn is structural not cyclical he is way over his head in the quicksand of the orthodoxy.

Let’s start with his simple bold assertion:

“Consider the new U.S. unemployment announcement. If you are a college graduate, there is no employment crisis. 72.7 percent of the college-educated population age-25 and over is working. The unemployment rate is 4.1 percent. Incomes are good.”

Umm, no, that’s not right. If we go back to 2007 we would see that the unemployment rate for college grads was 1.9 percent at its low that year, less than half of the current rate. It averaged 1.6 percent in 2000.

Unemployment Rate for College Grads, 25 years and Over

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

If the current unemployment in the U.S. economy were structural than we should expect to see lower than normal for these college grads whose labor is in short supply. Instead, we see that their unemployment rate is more than twice the pre-recession level and close two and half times its 2000 level.

We should also expect to see that real wages for college grads are rising rapidly. They aren’t. They have not even kept pace with inflation for the last dozen years.

In short, Sachs does not even have the beginning of an argument here. He’d better find some new data or give up his argument that the causes of unemployment are structural. His data indicate the opposite.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a lengthy story on the possibilities of manufacturing electronics in the United States. Near the end of the piece it discusses divisions in the Obama administration on measures to try to bring more manufacturing back to the United States.

On the one hand, it notes the view of Ron Bloom, who had been the president’s senior advisor on manufacturing policy, that the U.S. should take steps to push down the value of the dollar in order to make manufacturing in the United States more competitive. It then contrasts this view with that of Lawrence H. Summers, formerly the top economic adviser to Obama. The piece tells readers:

“along with many economists, Mr. Summers argued that an overly aggressive trade stance could hurt manufacturing — by, for instance, pushing up the price of imported steel used by carmakers — and over time, drive companies away. “

Actually, standard economic theory would argue that a lower valued dollar is exactly the mechanism through which the trade deficit should be brought down. In a system of floating exchange rates, the excess supply of currency on world markets from a deficit country like the United States is supposed to bring down the value of its currency. This makes its goods more competitive in world markets, reducing the size of its trade deficit.

The expected drop in the value of the currency is not taking place today with the dollar because a number of countries are buying up large amounts of dollars in order to prop up its value against their own currencies. By keeping the dollar over-valued they are able to sustain their trade surpluses with the United States.

It is worth noting that by definition, if the United States has a large trade deficit then the country has large negative national savings. This means that by supporting a policy that leads to a large trade deficit, Summers was arguing for either large budget deficits and/or large negative private savings, as we saw at the peak of the housing bubble. Perhaps Mr. Summers does not understand the implications of his position, but there is no logical way around it.

It is also worth noting that the over-valued dollar policy supported by Summers acts to redistribute income from workers who are exposed to international competition, like manufacturing workers, to workers who are largely protected from international competition, like doctors, lawyers and other highly educated professionals. In other words, it can be seen as one of the policies that redistributes money from the 99 percent to the one percent.

The NYT ran a lengthy story on the possibilities of manufacturing electronics in the United States. Near the end of the piece it discusses divisions in the Obama administration on measures to try to bring more manufacturing back to the United States.

On the one hand, it notes the view of Ron Bloom, who had been the president’s senior advisor on manufacturing policy, that the U.S. should take steps to push down the value of the dollar in order to make manufacturing in the United States more competitive. It then contrasts this view with that of Lawrence H. Summers, formerly the top economic adviser to Obama. The piece tells readers:

“along with many economists, Mr. Summers argued that an overly aggressive trade stance could hurt manufacturing — by, for instance, pushing up the price of imported steel used by carmakers — and over time, drive companies away. “

Actually, standard economic theory would argue that a lower valued dollar is exactly the mechanism through which the trade deficit should be brought down. In a system of floating exchange rates, the excess supply of currency on world markets from a deficit country like the United States is supposed to bring down the value of its currency. This makes its goods more competitive in world markets, reducing the size of its trade deficit.

The expected drop in the value of the currency is not taking place today with the dollar because a number of countries are buying up large amounts of dollars in order to prop up its value against their own currencies. By keeping the dollar over-valued they are able to sustain their trade surpluses with the United States.

It is worth noting that by definition, if the United States has a large trade deficit then the country has large negative national savings. This means that by supporting a policy that leads to a large trade deficit, Summers was arguing for either large budget deficits and/or large negative private savings, as we saw at the peak of the housing bubble. Perhaps Mr. Summers does not understand the implications of his position, but there is no logical way around it.

It is also worth noting that the over-valued dollar policy supported by Summers acts to redistribute income from workers who are exposed to international competition, like manufacturing workers, to workers who are largely protected from international competition, like doctors, lawyers and other highly educated professionals. In other words, it can be seen as one of the policies that redistributes money from the 99 percent to the one percent.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Catherine Rampell had an interesting discussion of the Fed’s likely course of action at its September meeting based on the July numbers. While the piece acknowledged the July jobs number from the establishment survey was somewhat better than expected, it concludes that the Fed is likely to move based on the weakness of the data from the household survey.

I’d have to disagree with that assessment. The household survey is far more erratic than the establishment survey. For example, it shows a jump of 422,000 jobs in May. Anyone remember that boom? Last June it reported a drop of 423,000. In August and September the household survey showed a combined gain of 657,000 jobs at a time when many news accounts were debating the likelihood of a double-dip recession.

It is easy to go back and find large one or even two month jumps or plunges in employment in the household survey that correspond to nothing that can be identified in the economy at the time. The Fed is surely aware of the household survey’s erratic pattern.

This means that when they sit down at their September meeting, the major news they will be considering on the labor market front will be the establishment survey. While the July data should warrant stronger steps to boost the economy (it will take 160 months of job growth at this pace to restore full employment), since they were not prepared to move before the July report, it is unlikely that a better than expected jobs number will prompt action.

Of course they will also have the August numbers by then.

Catherine Rampell had an interesting discussion of the Fed’s likely course of action at its September meeting based on the July numbers. While the piece acknowledged the July jobs number from the establishment survey was somewhat better than expected, it concludes that the Fed is likely to move based on the weakness of the data from the household survey.

I’d have to disagree with that assessment. The household survey is far more erratic than the establishment survey. For example, it shows a jump of 422,000 jobs in May. Anyone remember that boom? Last June it reported a drop of 423,000. In August and September the household survey showed a combined gain of 657,000 jobs at a time when many news accounts were debating the likelihood of a double-dip recession.

It is easy to go back and find large one or even two month jumps or plunges in employment in the household survey that correspond to nothing that can be identified in the economy at the time. The Fed is surely aware of the household survey’s erratic pattern.

This means that when they sit down at their September meeting, the major news they will be considering on the labor market front will be the establishment survey. While the July data should warrant stronger steps to boost the economy (it will take 160 months of job growth at this pace to restore full employment), since they were not prepared to move before the July report, it is unlikely that a better than expected jobs number will prompt action.

Of course they will also have the August numbers by then.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A piece that noted the slow pace of the recovery and compared it to other recessions never once mentioned the housing bubble. The fact that this recession was brought on by the collapse of a housing bubble, as opposed to the Fed raising interest rates to slow the economy, makes it qualitatively different from prior post-war recessions with the exception of the 2001 downturn that was brought on by the collapse of the stock bubble. It would have been worth making this point instead of turning the discussion into a he said/she said that concludes:

“‘The debate is unresolvable,’ said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the American Action Forum, a center-right think tank, and the former director of the Congressional Budget Office. ‘We don’t have a lot of data points. We only have about a dozen recessions where we have a lot of data.'”

A piece that noted the slow pace of the recovery and compared it to other recessions never once mentioned the housing bubble. The fact that this recession was brought on by the collapse of a housing bubble, as opposed to the Fed raising interest rates to slow the economy, makes it qualitatively different from prior post-war recessions with the exception of the 2001 downturn that was brought on by the collapse of the stock bubble. It would have been worth making this point instead of turning the discussion into a he said/she said that concludes:

“‘The debate is unresolvable,’ said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the American Action Forum, a center-right think tank, and the former director of the Congressional Budget Office. ‘We don’t have a lot of data points. We only have about a dozen recessions where we have a lot of data.'”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Binyamin Appelbaum has an interesting piece reminding readers of the importance of the seasonal adjustments in the job numbers that are released each month. It points out that July has the second largest positive seasonal adjustment, after January, of any month. (I don’t quite understand the chart, which seems to show positive seasonal adjustments for every month.) For example, last year the seasonal adjustment added 1.3 million jobs to the raw data, turning the seasonally adjusted number into a gain of 96,000 jobs, despite an unadjusted loss of 1.3 million jobs. Appelbaum’s point is that a small error in the size of the adjustment would have a huge impact on the jobs number reported for July.

The point is actually even more important than Appelbaum suggests. There are very large changes in employment month to month for seasonal factors that have nothing directly to do with the state of the economy. When these patterns change then the jobs numbers will give us a misleading picture of the state of the economy.

That is why the unusually warm winter weather gave an overly optimistic picture of the economy. Since this job growth was borrowed from the spring, the subsequent months gave us an overly pessimistic picture of the economy. Seasonal patterns can also change for reasons not directly related to weather. For example, stores now start holiday sales as early as October and the auto industry no longer shuts down all their factories in July for retooling.

Anyhow, Appelbaum is right to remind us about the importance of seasonal factors in the jobs numbers. We might not need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows, but we do need one to know how the economy is doing.

Binyamin Appelbaum has an interesting piece reminding readers of the importance of the seasonal adjustments in the job numbers that are released each month. It points out that July has the second largest positive seasonal adjustment, after January, of any month. (I don’t quite understand the chart, which seems to show positive seasonal adjustments for every month.) For example, last year the seasonal adjustment added 1.3 million jobs to the raw data, turning the seasonally adjusted number into a gain of 96,000 jobs, despite an unadjusted loss of 1.3 million jobs. Appelbaum’s point is that a small error in the size of the adjustment would have a huge impact on the jobs number reported for July.

The point is actually even more important than Appelbaum suggests. There are very large changes in employment month to month for seasonal factors that have nothing directly to do with the state of the economy. When these patterns change then the jobs numbers will give us a misleading picture of the state of the economy.

That is why the unusually warm winter weather gave an overly optimistic picture of the economy. Since this job growth was borrowed from the spring, the subsequent months gave us an overly pessimistic picture of the economy. Seasonal patterns can also change for reasons not directly related to weather. For example, stores now start holiday sales as early as October and the auto industry no longer shuts down all their factories in July for retooling.

Anyhow, Appelbaum is right to remind us about the importance of seasonal factors in the jobs numbers. We might not need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows, but we do need one to know how the economy is doing.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

When it comes to tax plans, it’s all just so confusing. Or at least that’s what the NYT seems to be telling us.

The NYT ran an article that reports on a study by the Tax Policy Center that showed Governor Romney’s tax plan would lead to a large reduction in taxes for the wealthy, while raising taxes for everyone else. It then cites Romney’s claim that his tax plan is similar to the one developed by Morgan Stanley director Erskine Bowles and former Senator Alan Simpson, the co-chairs of President Obama’s deficit commission. The piece goes on to tell readers:

“The Simpson-Bowles plan called for reduced income tax rates, but it would have raised about $2 trillion more in tax revenues over 10 years, mostly from high-income taxpayers.”

Wow, this should really leave us scratching our heads. After all, if Romney’s plan is similar to the Bowles-Simpson plan, and the Bowles-Simpson plan would raise $2 trillion, mostly from high income taxpayers, then the Romney plan must also increase revenue from high income taxpayers. But, then the Tax Policy Center study would be wrong. What is a careful NYT reader to think?

The NYT could have resolved this seeming paradox by pointing out an important difference between the Romney plan and the Bowles-Simpson plan. Romney has explicitly said that he would not change any of the tax incentives for saving. This means that he has ruled out raising the tax rate on capital gains and dividends or curtailing some of the tax benefits for IRAs and 401(k)s. This makes his plan much more friendly to upper income taxpayers, who are the primary beneficiaries of these tax breaks.

Perhaps the NYT assumed that all its readers already knew about this difference between the Romney plan and the Bowles-Simpson plan, but it still would have been worth reminding them.

When it comes to tax plans, it’s all just so confusing. Or at least that’s what the NYT seems to be telling us.

The NYT ran an article that reports on a study by the Tax Policy Center that showed Governor Romney’s tax plan would lead to a large reduction in taxes for the wealthy, while raising taxes for everyone else. It then cites Romney’s claim that his tax plan is similar to the one developed by Morgan Stanley director Erskine Bowles and former Senator Alan Simpson, the co-chairs of President Obama’s deficit commission. The piece goes on to tell readers:

“The Simpson-Bowles plan called for reduced income tax rates, but it would have raised about $2 trillion more in tax revenues over 10 years, mostly from high-income taxpayers.”

Wow, this should really leave us scratching our heads. After all, if Romney’s plan is similar to the Bowles-Simpson plan, and the Bowles-Simpson plan would raise $2 trillion, mostly from high income taxpayers, then the Romney plan must also increase revenue from high income taxpayers. But, then the Tax Policy Center study would be wrong. What is a careful NYT reader to think?

The NYT could have resolved this seeming paradox by pointing out an important difference between the Romney plan and the Bowles-Simpson plan. Romney has explicitly said that he would not change any of the tax incentives for saving. This means that he has ruled out raising the tax rate on capital gains and dividends or curtailing some of the tax benefits for IRAs and 401(k)s. This makes his plan much more friendly to upper income taxpayers, who are the primary beneficiaries of these tax breaks.

Perhaps the NYT assumed that all its readers already knew about this difference between the Romney plan and the Bowles-Simpson plan, but it still would have been worth reminding them.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión