I have often used to space to harangue news outlets for making too much of relatively small changes in weekly unemployment insurance (UI) claims. After all, it is just one week’s worth of data. The numbers are erratic and subject to substantial revision.

Still, I would have thought the decline in claims reported yesterday would have gotten some more attention. It wasn’t so much the single week decline that was newsworthy as the fact that the 4-week moving average, 367,250 was very close to the low for the recovery that we saw back in February.

More rapid job growth usually does follow declines in UI claims, although the relationship is far from exact. Nonetheless, the new claims seen over the last month is consistent with a much more rapid pace of job growth than we have been seeing. My bet for July is now in excess of 160k with some upward revision to the June number.

That’s still not really worth celebrating given our jobs deficit, but it is a step in the right direction.

I have often used to space to harangue news outlets for making too much of relatively small changes in weekly unemployment insurance (UI) claims. After all, it is just one week’s worth of data. The numbers are erratic and subject to substantial revision.

Still, I would have thought the decline in claims reported yesterday would have gotten some more attention. It wasn’t so much the single week decline that was newsworthy as the fact that the 4-week moving average, 367,250 was very close to the low for the recovery that we saw back in February.

More rapid job growth usually does follow declines in UI claims, although the relationship is far from exact. Nonetheless, the new claims seen over the last month is consistent with a much more rapid pace of job growth than we have been seeing. My bet for July is now in excess of 160k with some upward revision to the June number.

That’s still not really worth celebrating given our jobs deficit, but it is a step in the right direction.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a piece on the new Congressional Budget Office estimates of the cost and coverage rates for the Affordable Care Act following the changes required by the Supreme Court ruling. It concluded the piece with a classic he said/she said:

“Representative Tom Price of Georgia, chairman of the House Republican Policy Committee, said the law was unaffordable, and he pointed to the $1.7 trillion price tag mentioned by the budget office.

But Representative Allyson Y. Schwartz, Democrat of Pennsylvania, said the law was a good deal that would ‘save $109 billion over the next decade, while increasing access to health care for millions of Americans.'”

Well that settles it, the paper has done its job.

How about telling us how large this sum is relative to projected income (about 0.85 percent)? How about as a share of projected federal spending (about 4.0 percent)? Maybe the paper could compare to the size of the tax cuts proposed by governor Romney (less than 50 percent)?

The he said/she said at the end of this piece is killing trees for nothing. It provides no useful information to readers. (We already knew that Republicans didn’t like the plan and Democrats do.) It would have required minimal effort to put these numbers in a context that provided useful information to readers.

The NYT ran a piece on the new Congressional Budget Office estimates of the cost and coverage rates for the Affordable Care Act following the changes required by the Supreme Court ruling. It concluded the piece with a classic he said/she said:

“Representative Tom Price of Georgia, chairman of the House Republican Policy Committee, said the law was unaffordable, and he pointed to the $1.7 trillion price tag mentioned by the budget office.

But Representative Allyson Y. Schwartz, Democrat of Pennsylvania, said the law was a good deal that would ‘save $109 billion over the next decade, while increasing access to health care for millions of Americans.'”

Well that settles it, the paper has done its job.

How about telling us how large this sum is relative to projected income (about 0.85 percent)? How about as a share of projected federal spending (about 4.0 percent)? Maybe the paper could compare to the size of the tax cuts proposed by governor Romney (less than 50 percent)?

The he said/she said at the end of this piece is killing trees for nothing. It provides no useful information to readers. (We already knew that Republicans didn’t like the plan and Democrats do.) It would have required minimal effort to put these numbers in a context that provided useful information to readers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson’s column lays out the factors that caused the huge surplus predicted for the last decade by the Congressional Budget Office to turn into a huge deficit. Samuelson cites analysis of the $12 trillion shift from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and two “non-partisan” groups, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget and the Pew Fiscal Initiative.

Samuelson and these groups are careful to say that blame for this shift is widely shared, but that the largest chunk stems from weaker than projected economic growth and changes in technical assumptions. If we look more closely at the weaker than expected economic growth and some of those technical assumptions, the picture gets a bit more interesting.

The economy grew much more slowly than expected in 2001 and 2002 because of the collapse of a stock bubble. It grew much less rapidly than expected in 2008 and 2009 because of a collapse of the housing bubble. Some of the “technical changes” were the result of much lower capital gains income than had been projected. That is what happens when a bubble bursts. (The official data probably understates the falloff, since it is likely that much capital gains income shows up as normal income.)

In short, the main reason that the CBO projections understated the deficits over the last decade was that it twice failed to recognize asset bubbles. In fact, the impact of this failure on projections is even larger since some items on the Samuelson deficit list would not have been there absent the slower growth, like the Obama stimulus.

So there is a clear villain in this story, economic analysts who were too incompetent to recognize two huge bubbles and the impact that their collapse would have on the economy. Unfortunately, in Washington policy circles, such failures are a badge of honor (“who could have known?” is the official motto in these parts), so these folks continue to hold their jobs and get regular promotions and increased authority.

While we might prefer to see people with better knowledge of the economy in positions of responsibility, there is a bright side. These jobs keep people without marketable skills employed.

Robert Samuelson’s column lays out the factors that caused the huge surplus predicted for the last decade by the Congressional Budget Office to turn into a huge deficit. Samuelson cites analysis of the $12 trillion shift from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and two “non-partisan” groups, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget and the Pew Fiscal Initiative.

Samuelson and these groups are careful to say that blame for this shift is widely shared, but that the largest chunk stems from weaker than projected economic growth and changes in technical assumptions. If we look more closely at the weaker than expected economic growth and some of those technical assumptions, the picture gets a bit more interesting.

The economy grew much more slowly than expected in 2001 and 2002 because of the collapse of a stock bubble. It grew much less rapidly than expected in 2008 and 2009 because of a collapse of the housing bubble. Some of the “technical changes” were the result of much lower capital gains income than had been projected. That is what happens when a bubble bursts. (The official data probably understates the falloff, since it is likely that much capital gains income shows up as normal income.)

In short, the main reason that the CBO projections understated the deficits over the last decade was that it twice failed to recognize asset bubbles. In fact, the impact of this failure on projections is even larger since some items on the Samuelson deficit list would not have been there absent the slower growth, like the Obama stimulus.

So there is a clear villain in this story, economic analysts who were too incompetent to recognize two huge bubbles and the impact that their collapse would have on the economy. Unfortunately, in Washington policy circles, such failures are a badge of honor (“who could have known?” is the official motto in these parts), so these folks continue to hold their jobs and get regular promotions and increased authority.

While we might prefer to see people with better knowledge of the economy in positions of responsibility, there is a bright side. These jobs keep people without marketable skills employed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Reuters must be trying to win a Pulitzer in the bad business reporting category (sorry folks, you’ve got some stiff competition). The headline of a piece on the Commerce Department’s report on new home sales for June warned of the largest drop in sales more than a year. Are you scared?

If you look at the data, you would notice that May had one of the biggest jumps in sales in the last year, raising the rate to the highest level since the fall of 2008. Furthermore, three quarters of the drop was explained by a 60 percent decline in new homes sales in the Northeast. That could be real, but my guess is that this is some artifact of reporting that will be corrected when these numbers are revised next month. (I have not heard about the collapse of the economies in in NY, NJ, and MA.)

A little context would be helpful on this one. If May and June’s sales are averaged, we would be seeing a strong uptick in sales compared to earlier this year.

Reuters must be trying to win a Pulitzer in the bad business reporting category (sorry folks, you’ve got some stiff competition). The headline of a piece on the Commerce Department’s report on new home sales for June warned of the largest drop in sales more than a year. Are you scared?

If you look at the data, you would notice that May had one of the biggest jumps in sales in the last year, raising the rate to the highest level since the fall of 2008. Furthermore, three quarters of the drop was explained by a 60 percent decline in new homes sales in the Northeast. That could be real, but my guess is that this is some artifact of reporting that will be corrected when these numbers are revised next month. (I have not heard about the collapse of the economies in in NY, NJ, and MA.)

A little context would be helpful on this one. If May and June’s sales are averaged, we would be seeing a strong uptick in sales compared to earlier this year.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

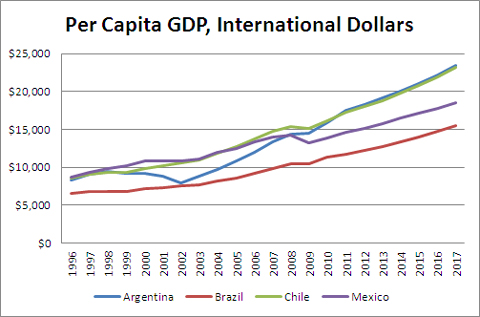

As noted previously, the Washington Post has a huge stake in saying that NAFTA was a success. As a result, it simply cannot honestly discuss the state of Mexico’s economy in either its news or opinion pages. Today it has a piece that is headlined on the main page of its web site as “Mexico’s middle class begins to boom.” Readers would never know that Mexico has had the worst growth record in all of Latin America over the last decade.

Since the Post seems intent on recycling misleading news stories, I will recycle my comments. The segment below is from July 1 of this year:

The Washington Post is heavily invested in NAFTA. At the time of the debate it abandoned any pretext of being an objective newspaper, allowing both its opinion and news pages to be overwhelmingly dominated by proponents of the agreement. Since its passage the Post has refused to acknowledge that the agreement has had the intended effect in the United States of lowering the wages of manufacturing workers. (This is textbook economics. By putting U.S. manufacturing workers into more direct competition with their low-paid counterparts in Mexico, the result is that wages of manufacturing workers in the United States fall.)

The Post also refuses to acknowledge that the deal has failed to improve Mexico’s growth. In fact, a lead Post editorial in December 2007 told readers that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled since 1988, which it attributed to the benefits of NAFTA. The actual increase over this 19 year period was 83 percent, which put Mexico near the bottom in growth for Latin American countries.

The Post’s prohibition of honest discussion of Mexico’s economy is apparently continuing. In a piece on Mexico’s elections today, the Post told readers:

“But annual growth during Calderon’s six years has averaged a middling 2 percent.”

This statement gives a whole new meaning to word “middling.” If we turn to the IMF’s data and look at per capita GDP growth in the years 2006-2011, we find that on average Mexico’s per capital GDP shrank by 0.1 percent annually over this period. This is not middling; this performance places Mexico dead last among Latin American countries (several countries in the Caribbean did worse.)

For some reference points, per capita growth in Argentina averaged 5.8 percent, Bolivia 2.8 percent, Brazil 3.1 percent, Ecuador 2.6 percent, and Peru 5.6 percent. There is nothing middling about Mexico’s economic performance over this period; it was bad.

And here’s a graph so that folks can put the Post’s graph showing the rise of Mexico’s per capita income in some context.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

See Mexico’s boom?

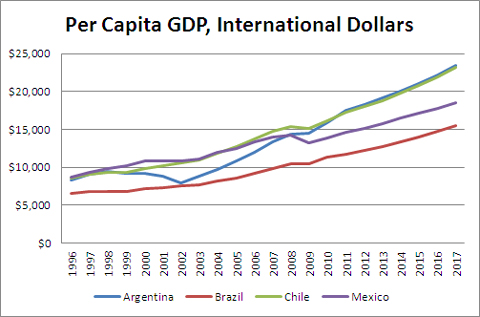

As noted previously, the Washington Post has a huge stake in saying that NAFTA was a success. As a result, it simply cannot honestly discuss the state of Mexico’s economy in either its news or opinion pages. Today it has a piece that is headlined on the main page of its web site as “Mexico’s middle class begins to boom.” Readers would never know that Mexico has had the worst growth record in all of Latin America over the last decade.

Since the Post seems intent on recycling misleading news stories, I will recycle my comments. The segment below is from July 1 of this year:

The Washington Post is heavily invested in NAFTA. At the time of the debate it abandoned any pretext of being an objective newspaper, allowing both its opinion and news pages to be overwhelmingly dominated by proponents of the agreement. Since its passage the Post has refused to acknowledge that the agreement has had the intended effect in the United States of lowering the wages of manufacturing workers. (This is textbook economics. By putting U.S. manufacturing workers into more direct competition with their low-paid counterparts in Mexico, the result is that wages of manufacturing workers in the United States fall.)

The Post also refuses to acknowledge that the deal has failed to improve Mexico’s growth. In fact, a lead Post editorial in December 2007 told readers that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled since 1988, which it attributed to the benefits of NAFTA. The actual increase over this 19 year period was 83 percent, which put Mexico near the bottom in growth for Latin American countries.

The Post’s prohibition of honest discussion of Mexico’s economy is apparently continuing. In a piece on Mexico’s elections today, the Post told readers:

“But annual growth during Calderon’s six years has averaged a middling 2 percent.”

This statement gives a whole new meaning to word “middling.” If we turn to the IMF’s data and look at per capita GDP growth in the years 2006-2011, we find that on average Mexico’s per capital GDP shrank by 0.1 percent annually over this period. This is not middling; this performance places Mexico dead last among Latin American countries (several countries in the Caribbean did worse.)

For some reference points, per capita growth in Argentina averaged 5.8 percent, Bolivia 2.8 percent, Brazil 3.1 percent, Ecuador 2.6 percent, and Peru 5.6 percent. There is nothing middling about Mexico’s economic performance over this period; it was bad.

And here’s a graph so that folks can put the Post’s graph showing the rise of Mexico’s per capita income in some context.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

See Mexico’s boom?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It must be very hard to get news at Fox on 15th Street. In the Post’s little primer giving “steps of the euro crisis” step number 3 tells us about the end of cheap credit:

“Following the U.S. credit crisis in 2008, Greece reported a huge deficit increase that suddenly made investors worried about its ability to pay back its loans. High deficits in Portugal, Spain and Ireland caused the price of credit to rise in those countries as well.”

This is an interesting story, but it left out an important part of the picture. Spain and Ireland had been running large budget surpluses prior to the downturn. They were running large deficits in 2008 because they had housing bubbles that collapsed and sent their economies plummeting into recession.

Apparently the Post could not find information about these bubbles or the path of government finances in euro zone countries prior to the downturn.

It must be very hard to get news at Fox on 15th Street. In the Post’s little primer giving “steps of the euro crisis” step number 3 tells us about the end of cheap credit:

“Following the U.S. credit crisis in 2008, Greece reported a huge deficit increase that suddenly made investors worried about its ability to pay back its loans. High deficits in Portugal, Spain and Ireland caused the price of credit to rise in those countries as well.”

This is an interesting story, but it left out an important part of the picture. Spain and Ireland had been running large budget surpluses prior to the downturn. They were running large deficits in 2008 because they had housing bubbles that collapsed and sent their economies plummeting into recession.

Apparently the Post could not find information about these bubbles or the path of government finances in euro zone countries prior to the downturn.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Andrew Biggs, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute, is one of the more serious and careful people arguing conservative positions on policy issues. Nonetheless, he strikes out badly in trying to catch me in a contradiction. (Excuse the self-indulgence, consider this a carryover from my birthday boasts.)

Andrew has a blog post where he apparently believes that he has really got me [thanks gov wonk]. I have authored or co-authored several items recently on public pensions in which I argued that it is almost impossible to imagine scenarios in which pensions get returns on their stock holdings that are markedly worse than what they are assuming in their projections (e.g. here and here).

Andrew has my projected returns as averaging 8.9 percent in the current decade and 8.2 percent in the next two decades. (That’s not quite right, but close enough.) He then pulls out his gotcha, a paper from 2000 in which I projected stock returns of 3.4 percent for the first two decades and 3.5 percent for the 2030s. (In a note he points out that he forgot to add 2.8 percent for the inflation rate assumed by the Social Security trustees, whose assumptions provided the basis for my projections.)

So Andrew has me projected 8.9 percent returns and 8.2 percent returns when I was making projections of 6.4 percent and 6.5 percent back in 2000. Should I be wearing a paper bag over my head for the next year in shame?

Perhaps I should, but not because of Andrew’s discovery. In that 2000 paper I wrote:

“It is reasonable to believe … that stocks are temporarily over-valued, and that price-to-earnings ratios will soon fall back to more normal levels [this is the ratio of stock prices to trend earnings]. However, if this is the basis for assuming that stocks will provide their historic rates of return in the future, it would be necessary to include a large decline in stock prices in the projections.”

Andrew probably missed it, but we did in fact have a large decline in stock prices (two actually) between 2000 and the present. That is why I am now confident that we can expect higher rates of return in the future. In other words, I have been 100 percent consistent in my projections of returns, what has changed is the market itself.

I appreciate Andrew’s efforts to remind everyone that I called the stock bubble back in 2000 (actually first in 1997).

Andrew Biggs, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute, is one of the more serious and careful people arguing conservative positions on policy issues. Nonetheless, he strikes out badly in trying to catch me in a contradiction. (Excuse the self-indulgence, consider this a carryover from my birthday boasts.)

Andrew has a blog post where he apparently believes that he has really got me [thanks gov wonk]. I have authored or co-authored several items recently on public pensions in which I argued that it is almost impossible to imagine scenarios in which pensions get returns on their stock holdings that are markedly worse than what they are assuming in their projections (e.g. here and here).

Andrew has my projected returns as averaging 8.9 percent in the current decade and 8.2 percent in the next two decades. (That’s not quite right, but close enough.) He then pulls out his gotcha, a paper from 2000 in which I projected stock returns of 3.4 percent for the first two decades and 3.5 percent for the 2030s. (In a note he points out that he forgot to add 2.8 percent for the inflation rate assumed by the Social Security trustees, whose assumptions provided the basis for my projections.)

So Andrew has me projected 8.9 percent returns and 8.2 percent returns when I was making projections of 6.4 percent and 6.5 percent back in 2000. Should I be wearing a paper bag over my head for the next year in shame?

Perhaps I should, but not because of Andrew’s discovery. In that 2000 paper I wrote:

“It is reasonable to believe … that stocks are temporarily over-valued, and that price-to-earnings ratios will soon fall back to more normal levels [this is the ratio of stock prices to trend earnings]. However, if this is the basis for assuming that stocks will provide their historic rates of return in the future, it would be necessary to include a large decline in stock prices in the projections.”

Andrew probably missed it, but we did in fact have a large decline in stock prices (two actually) between 2000 and the present. That is why I am now confident that we can expect higher rates of return in the future. In other words, I have been 100 percent consistent in my projections of returns, what has changed is the market itself.

I appreciate Andrew’s efforts to remind everyone that I called the stock bubble back in 2000 (actually first in 1997).

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión