Most people probably think that presidential campaigns are about getting the support of powerful political actors and interest groups. However the NYT told readers that they are wrong to believe this. Instead, the NYT told readers in a headline that:

“philosophical clash over government’s role highlights parties divide.”

In fact, as the article makes clear there is not really a philosophical clash at stake here. Governor Romney was deliberately misrepresenting a comment made by President Obama to imply that “he does not believe in individual success or the free market.”

While the article does it best to tell readers that there are philosophical issues at stake all the evidence suggests that Romney’s supporters would like to pay less in taxes so that they will have more money. President Obama is trying to appeal to interest groups that will benefit from government programs like Medicare and student loans.

There is nothing in the article to support its assertion that:

“the choice between Mr. Obama and Mr. Romney presents voters with starkly different philosophies about the role of government in American society.”

In fact both candidates believe that the government should intervene to provide too big to fail protection to large banks, a subsidy worth tens of billions of dollar a year. They believe that the government should grant drug companies patent monopolies that will increase the cost of drugs by trillions of dollars over the next decade. And both candidates have supported a pattern of selective trade protection that redistributes money from ordinary workers to corporations and highly educated professionals.

These areas of agreement about the government’s role in the economy dwarf the areas of difference. The effort of the NYT to inflate the importance of relatively small differences on the government’s role and to transform an argument between competing interest groups into a matter of philosophy does not belong in the news section. [Thanks Joe]

Most people probably think that presidential campaigns are about getting the support of powerful political actors and interest groups. However the NYT told readers that they are wrong to believe this. Instead, the NYT told readers in a headline that:

“philosophical clash over government’s role highlights parties divide.”

In fact, as the article makes clear there is not really a philosophical clash at stake here. Governor Romney was deliberately misrepresenting a comment made by President Obama to imply that “he does not believe in individual success or the free market.”

While the article does it best to tell readers that there are philosophical issues at stake all the evidence suggests that Romney’s supporters would like to pay less in taxes so that they will have more money. President Obama is trying to appeal to interest groups that will benefit from government programs like Medicare and student loans.

There is nothing in the article to support its assertion that:

“the choice between Mr. Obama and Mr. Romney presents voters with starkly different philosophies about the role of government in American society.”

In fact both candidates believe that the government should intervene to provide too big to fail protection to large banks, a subsidy worth tens of billions of dollar a year. They believe that the government should grant drug companies patent monopolies that will increase the cost of drugs by trillions of dollars over the next decade. And both candidates have supported a pattern of selective trade protection that redistributes money from ordinary workers to corporations and highly educated professionals.

These areas of agreement about the government’s role in the economy dwarf the areas of difference. The effort of the NYT to inflate the importance of relatively small differences on the government’s role and to transform an argument between competing interest groups into a matter of philosophy does not belong in the news section. [Thanks Joe]

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a column today on rebalancing the global economy by Li Congjun, the head of Xinhua News Agency. While the article talks about the United States consuming too much and China consuming too little, remarkably the piece never once mentions currency values.

If the United States reduces its consumption, without a corresponding reduction in the value of the dollar, the textbook econ tells us that it just leads to unemployment, not a rebalancing. The events of the last four years have kindly proven the textbooks to be correct on this point.

Similarly, the textbook tells us that if China increases consumption, without also having a sharp rise in the value of its currency, then it will lead to inflation. China’s experience has also proven the textbook economics right.

It would have been useful to have this piece written by someone who would at least acknowledge basic economics.

The NYT had a column today on rebalancing the global economy by Li Congjun, the head of Xinhua News Agency. While the article talks about the United States consuming too much and China consuming too little, remarkably the piece never once mentions currency values.

If the United States reduces its consumption, without a corresponding reduction in the value of the dollar, the textbook econ tells us that it just leads to unemployment, not a rebalancing. The events of the last four years have kindly proven the textbooks to be correct on this point.

Similarly, the textbook tells us that if China increases consumption, without also having a sharp rise in the value of its currency, then it will lead to inflation. China’s experience has also proven the textbook economics right.

It would have been useful to have this piece written by someone who would at least acknowledge basic economics.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Pensions saw strong double-digit returns in the last years of the 90s. They had negative returns in the first years of the last decade. If anyone extrapolated from the last three years of the 90s and predicted double digit returns for the decades ahead or the first three years of the last decade and predicted flat or negative returns, they should have been taken far away from any position with any responsibility for pensions.

Unfortunately, the world does not work this way. Such absurd extrapolations are common practice as Sacramento Bee columnist Dan Walters showed us in a discussion of the returns on California pensions. Not only is it foolish to assume that a recent past of low returns will translate into low returns in the future and vice versa, the opposite is in fact true.

The plunge in trend price to earnings ratios (PEs) associated with the collapse of the stock bubble in 2000-2002 meant that it was possible for the stock market to provide higher returns over a sustained period. In the same way, the run-up of PEs to unprecedented levels at the end of the 90s ensured that returns would have to be lower in the future.

Those familiar with arithmetic understand this simple point. Unfortunately, relatively few such people are admitted to the debate over pension fund accounting.

Pensions saw strong double-digit returns in the last years of the 90s. They had negative returns in the first years of the last decade. If anyone extrapolated from the last three years of the 90s and predicted double digit returns for the decades ahead or the first three years of the last decade and predicted flat or negative returns, they should have been taken far away from any position with any responsibility for pensions.

Unfortunately, the world does not work this way. Such absurd extrapolations are common practice as Sacramento Bee columnist Dan Walters showed us in a discussion of the returns on California pensions. Not only is it foolish to assume that a recent past of low returns will translate into low returns in the future and vice versa, the opposite is in fact true.

The plunge in trend price to earnings ratios (PEs) associated with the collapse of the stock bubble in 2000-2002 meant that it was possible for the stock market to provide higher returns over a sustained period. In the same way, the run-up of PEs to unprecedented levels at the end of the 90s ensured that returns would have to be lower in the future.

Those familiar with arithmetic understand this simple point. Unfortunately, relatively few such people are admitted to the debate over pension fund accounting.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT devoted a lengthy article to the difference in experiences and opportunities for women and their children when there is a second earner in the household as opposed to a situation where the woman is raising children by herself. While the growth in the number of single parent families has been one of the factors increasing inequality among families with children, most of the impact of this change in family structure had been felt by 1985 according to a study by Bruce Western, which is cited in the article.

As pointed out by my colleague Shawn Fremstad, Western finds that the effect of changing family structure on inequality was negligible in the decade from 1985 to 1995 and actually was a factor reducing inequality in the decade from 1995 to 2005. In other words, this piece on the impact of changing family structure on the growth in inequality between families might have been an appropriate news story for 1985, but at this point it is a quarter century out of date. The vast majority of the rise in inequality in the last quarter century, and indeed in the whole period, is due to within group inequality meaning that it is due to the growth of inequality among families with the same number of wage earners and education levels. (Folks may also want to read Shawn’s follow-up post.)

The NYT devoted a lengthy article to the difference in experiences and opportunities for women and their children when there is a second earner in the household as opposed to a situation where the woman is raising children by herself. While the growth in the number of single parent families has been one of the factors increasing inequality among families with children, most of the impact of this change in family structure had been felt by 1985 according to a study by Bruce Western, which is cited in the article.

As pointed out by my colleague Shawn Fremstad, Western finds that the effect of changing family structure on inequality was negligible in the decade from 1985 to 1995 and actually was a factor reducing inequality in the decade from 1995 to 2005. In other words, this piece on the impact of changing family structure on the growth in inequality between families might have been an appropriate news story for 1985, but at this point it is a quarter century out of date. The vast majority of the rise in inequality in the last quarter century, and indeed in the whole period, is due to within group inequality meaning that it is due to the growth of inequality among families with the same number of wage earners and education levels. (Folks may also want to read Shawn’s follow-up post.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A couple of weeks ago the Washington Post (a.k.a. “Fox on 15th Street”) gained notoriety for running a major news article based on a study funding by military contractors that warned of large job losses from cuts in military spending. Of course folks who know economics realize that in a downturn cuts in any type of government spending will lead to job loss. In fact, cuts in most forms of government spending will lead to larger job losses than cuts in military spending. In other words, there was no real news in this study, except that the numbers were likely exaggerated.

In keeping with this spirit, the Post published a news article today that warned that allowing the Bush tax cuts to expire for the richest 2 percent would be “placing an enormous strain on the already sluggish economic recovery” according to another business financed study. This assertion badly misrepresented the study’s findings.

The projections from the study are long-run effects. They are not effects that would be felt in an “already sluggish economic recovery,” unless the assumption is that the recovery will be sluggish for 5-10 years in the future. The reporter and/or editor should have noticed the difference between the long-run impact and the immediate effect. The projections discussed in the article are long-run projections, not effects that would be felt in the next year or two.

The other major failing of this piece is that it never accurately described what the study analyzed. It calculated the impact of a tax increase that is used for higher government consumption spending. It does not measure the impact of a tax increase that is used either for deficit reduction or investment in infrastructure and education. The model used in this analysis would likely to show that either of these two uses of higher tax revenue would lead to increases in output, jobs, and wages, not decreases.

A couple of weeks ago the Washington Post (a.k.a. “Fox on 15th Street”) gained notoriety for running a major news article based on a study funding by military contractors that warned of large job losses from cuts in military spending. Of course folks who know economics realize that in a downturn cuts in any type of government spending will lead to job loss. In fact, cuts in most forms of government spending will lead to larger job losses than cuts in military spending. In other words, there was no real news in this study, except that the numbers were likely exaggerated.

In keeping with this spirit, the Post published a news article today that warned that allowing the Bush tax cuts to expire for the richest 2 percent would be “placing an enormous strain on the already sluggish economic recovery” according to another business financed study. This assertion badly misrepresented the study’s findings.

The projections from the study are long-run effects. They are not effects that would be felt in an “already sluggish economic recovery,” unless the assumption is that the recovery will be sluggish for 5-10 years in the future. The reporter and/or editor should have noticed the difference between the long-run impact and the immediate effect. The projections discussed in the article are long-run projections, not effects that would be felt in the next year or two.

The other major failing of this piece is that it never accurately described what the study analyzed. It calculated the impact of a tax increase that is used for higher government consumption spending. It does not measure the impact of a tax increase that is used either for deficit reduction or investment in infrastructure and education. The model used in this analysis would likely to show that either of these two uses of higher tax revenue would lead to increases in output, jobs, and wages, not decreases.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, that is what Brooks told readers. His column today mourns the fact that Romney and Bain are being blasted for being capitalists. He then tells readers:

“Romney is going to have to define a vision of modern capitalism. …. Let’s face it, he’s not a heroic entrepreneur. He’s an efficiency expert.”

Brooks is certainly right that Romney is not a heroic entrepreneur, but it doesn’t follow that he is necessarily an efficiency expert either. The private equity folks like to tell stories of how they find poorly managed companies, clean them up, and then sell them for a big profit.

Undoubtedly there are cases where this is true, but these are likely the minority of companies that are taken over by private equity (PE) firms. Finding companies that can be quickly turned around by better management is not easy. After all, if it were easy to find better management, someone would have done it already (economist humor).

What PE is very good at is taking advantage of tax dodges. It’s likely that your stodgy family-run business has not kept up-to-date with the state of the art tax avoidance schemes. However PE companies do, and there can be big bucks in applying these modern tax avoidance schemes to old-fashioned businesses.

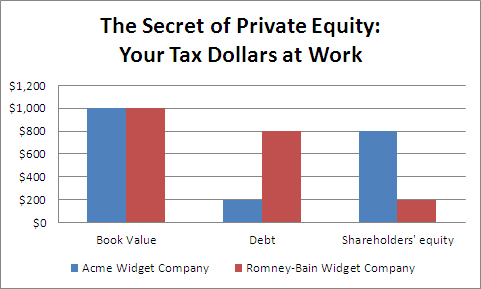

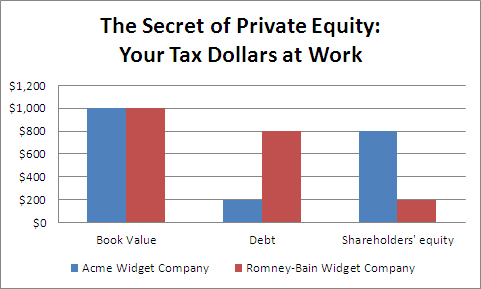

To see this, let’s take a simple example. Suppose an old widget company was operating with a ratio of debt to book value of 20 percent. Let’s assume that its book value is $1,000 million and its debt $200 million, leaving shareholders’ equity of $800 million.

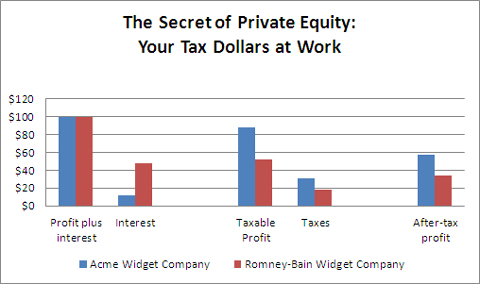

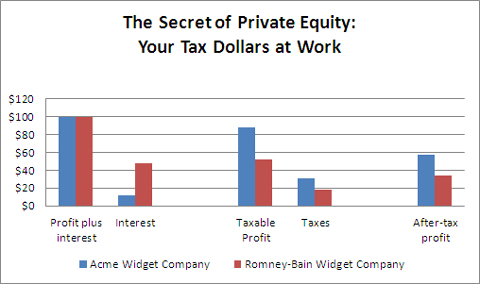

For simplicity, assume the combination of before tax profit and interest is 10 percent or $100 million. The company will then pay 6 percent interest ($12 million) on its debt. This leaves before tax profit of $88 million. if it pays a 35 percent tax rate, then its after tax profit is $57.2 million, as shown below.

Now suppose some clever PE types come in. One of the first things they will likely do is borrow a substantial amount, let’s say $600 million. They will use this money to repay much of the $800 million purchase price of company. The interest burden on the higher $800 million in debt ($600 million in new debt plus the old $200 million) is $48 million, leaving $52 million in before tax profits. Assuming that the company still pays 35 percent of its profits in taxes, its after-tax profit as a PE-owned company is $33.8 million.

While this means that our PE folks are taking home less from the widget company than the old-fashioned family owners, it is important to remember that they have gotten most of their money out of the operation. They only have $200 million invested, as compared to the $800 million invested by the previous owner, as illustrated below.

This means in principle that the Romney-Bain folks can find three other widget companies. If they do the same deal with each, they will manage to pocket over $135 million compared to the $57.2 million earned with the same amount of capital by the prior family owner.

Note that this increase in profitability assumes nothing about efficiency. In this story the Romney-Bain gang did nothing to improve the operation of the factory. They just found ways to reduce its tax liability.

This is clearly an overly-simplistic story, but it does illustrate how PE companies can make large profits without doing anything to increase efficiency. This is one of the ways in which PE companies make money. To get the full list, read the work of my colleague Eileen Appelbaum.

But the important point is that PE companies can make lots of money for themselves in ways that do not involve increasing efficiency. In other words, contrary to what Brooks told readers, there is no reason to assume that just because Romney got rich in PE that he is an efficiency expert.

Yes, that is what Brooks told readers. His column today mourns the fact that Romney and Bain are being blasted for being capitalists. He then tells readers:

“Romney is going to have to define a vision of modern capitalism. …. Let’s face it, he’s not a heroic entrepreneur. He’s an efficiency expert.”

Brooks is certainly right that Romney is not a heroic entrepreneur, but it doesn’t follow that he is necessarily an efficiency expert either. The private equity folks like to tell stories of how they find poorly managed companies, clean them up, and then sell them for a big profit.

Undoubtedly there are cases where this is true, but these are likely the minority of companies that are taken over by private equity (PE) firms. Finding companies that can be quickly turned around by better management is not easy. After all, if it were easy to find better management, someone would have done it already (economist humor).

What PE is very good at is taking advantage of tax dodges. It’s likely that your stodgy family-run business has not kept up-to-date with the state of the art tax avoidance schemes. However PE companies do, and there can be big bucks in applying these modern tax avoidance schemes to old-fashioned businesses.

To see this, let’s take a simple example. Suppose an old widget company was operating with a ratio of debt to book value of 20 percent. Let’s assume that its book value is $1,000 million and its debt $200 million, leaving shareholders’ equity of $800 million.

For simplicity, assume the combination of before tax profit and interest is 10 percent or $100 million. The company will then pay 6 percent interest ($12 million) on its debt. This leaves before tax profit of $88 million. if it pays a 35 percent tax rate, then its after tax profit is $57.2 million, as shown below.

Now suppose some clever PE types come in. One of the first things they will likely do is borrow a substantial amount, let’s say $600 million. They will use this money to repay much of the $800 million purchase price of company. The interest burden on the higher $800 million in debt ($600 million in new debt plus the old $200 million) is $48 million, leaving $52 million in before tax profits. Assuming that the company still pays 35 percent of its profits in taxes, its after-tax profit as a PE-owned company is $33.8 million.

While this means that our PE folks are taking home less from the widget company than the old-fashioned family owners, it is important to remember that they have gotten most of their money out of the operation. They only have $200 million invested, as compared to the $800 million invested by the previous owner, as illustrated below.

This means in principle that the Romney-Bain folks can find three other widget companies. If they do the same deal with each, they will manage to pocket over $135 million compared to the $57.2 million earned with the same amount of capital by the prior family owner.

Note that this increase in profitability assumes nothing about efficiency. In this story the Romney-Bain gang did nothing to improve the operation of the factory. They just found ways to reduce its tax liability.

This is clearly an overly-simplistic story, but it does illustrate how PE companies can make large profits without doing anything to increase efficiency. This is one of the ways in which PE companies make money. To get the full list, read the work of my colleague Eileen Appelbaum.

But the important point is that PE companies can make lots of money for themselves in ways that do not involve increasing efficiency. In other words, contrary to what Brooks told readers, there is no reason to assume that just because Romney got rich in PE that he is an efficiency expert.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Bill Keller used his NYT column today to outline a series of myths about President Obama’s health care plan. At one point he tells readers:

“I’m a pretty devout capitalist, and I see that in some cases individual responsibility helps contain wasteful spending on health care. If you have to share the cost of that extra M.R.I. or elective surgery, you’ll think hard about whether you really need it.”

The irony here is that under the current system it is government intervention that makes “the cost of that extra M.R.I.” expensive. The direct cost of an M.R.I., the electricity, the time of technicians to run the machine and the time of a doctor to read the results are relatively low. The machine itself however is expensive, because of government granted patent monopolies.

If M.R.I.s were sold in a free market, where anyone could copy the technology and sell an M.R.I. device for whatever the market would bear, then the cost of M.R.I. tests would not be a major issue.

Bill Keller used his NYT column today to outline a series of myths about President Obama’s health care plan. At one point he tells readers:

“I’m a pretty devout capitalist, and I see that in some cases individual responsibility helps contain wasteful spending on health care. If you have to share the cost of that extra M.R.I. or elective surgery, you’ll think hard about whether you really need it.”

The irony here is that under the current system it is government intervention that makes “the cost of that extra M.R.I.” expensive. The direct cost of an M.R.I., the electricity, the time of technicians to run the machine and the time of a doctor to read the results are relatively low. The machine itself however is expensive, because of government granted patent monopolies.

If M.R.I.s were sold in a free market, where anyone could copy the technology and sell an M.R.I. device for whatever the market would bear, then the cost of M.R.I. tests would not be a major issue.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That what readers of his column calling President Obama a “distributionalist” and Governor Romney an “expansionist” must have concluded. Samuelson tells readers:

“By ‘distributionalist,’ I mean that Obama sees government as an instrument to promote economic and social justice by redistributing the bounty of a wealthy society. Economic growth is not ignored but tends to be taken for granted or treated as a less important priority. How else, for example, to explain Obama’s decision to push the Affordable Care Act (the ACA or ‘Obamacare’) — a huge new social program — in the midst of the deepest economic downturn since the Great Depression?”

There are a couple of obvious answers to Samuelson’s “how else” question. First, President Obama made a stimulus package the first priority of his administration. His big mistake was that he listened to what the mainstream of the economics profession was saying at the time, and therefore believed that this would not be “the deepest economic downturn since the Great Depression.”

For those unable to remember back to 2009, many Republicans argued that the economy did not need any boost at all. This would include many of the people who Samuelson would no doubt call “expansionist.”

The other obvious answer to Samuelson’s question is that the key provisions in the ACA do not kick in until 2014, when most projections in 2009 showed the economy to have largely recovered from the downturn. This means that, insofar as the bill has negative impacts on the economy (it’s certainly not obvious why it would) the expectation at the time is that these would not be felt until the economy had pretty much recovered from the downturn. It is also worth noting that the ACA includes cost control provisions (Samuelson probably was unable to find a copy of the bill) that would, if effective, limit the extent to which health care costs pose a drain on the economy in the long-term.

Samuelson’s main reason for calling Romney an expansionist is that he wants to give more tax breaks to rich people. There is no evidence that this will lead to more rapid economic growth, although it will undoubtedly make rich people richer.

Romney also wants to get rid of regulations that limit the ability of too big to fail banks from getting even more profit from their implicit government subsidies. While this will also put more money in the pockets of the very wealthy, it has no obvious connection to economic growth. In fact, by diverting resources from productive sectors of the economy to the financial sector, Romney’s path would likely slow growth.

The evidence would suggest that Romney can best be characterized as a “distributionalist” in Samuelson’s terms, although his plan to is to redistribute upward.

That what readers of his column calling President Obama a “distributionalist” and Governor Romney an “expansionist” must have concluded. Samuelson tells readers:

“By ‘distributionalist,’ I mean that Obama sees government as an instrument to promote economic and social justice by redistributing the bounty of a wealthy society. Economic growth is not ignored but tends to be taken for granted or treated as a less important priority. How else, for example, to explain Obama’s decision to push the Affordable Care Act (the ACA or ‘Obamacare’) — a huge new social program — in the midst of the deepest economic downturn since the Great Depression?”

There are a couple of obvious answers to Samuelson’s “how else” question. First, President Obama made a stimulus package the first priority of his administration. His big mistake was that he listened to what the mainstream of the economics profession was saying at the time, and therefore believed that this would not be “the deepest economic downturn since the Great Depression.”

For those unable to remember back to 2009, many Republicans argued that the economy did not need any boost at all. This would include many of the people who Samuelson would no doubt call “expansionist.”

The other obvious answer to Samuelson’s question is that the key provisions in the ACA do not kick in until 2014, when most projections in 2009 showed the economy to have largely recovered from the downturn. This means that, insofar as the bill has negative impacts on the economy (it’s certainly not obvious why it would) the expectation at the time is that these would not be felt until the economy had pretty much recovered from the downturn. It is also worth noting that the ACA includes cost control provisions (Samuelson probably was unable to find a copy of the bill) that would, if effective, limit the extent to which health care costs pose a drain on the economy in the long-term.

Samuelson’s main reason for calling Romney an expansionist is that he wants to give more tax breaks to rich people. There is no evidence that this will lead to more rapid economic growth, although it will undoubtedly make rich people richer.

Romney also wants to get rid of regulations that limit the ability of too big to fail banks from getting even more profit from their implicit government subsidies. While this will also put more money in the pockets of the very wealthy, it has no obvious connection to economic growth. In fact, by diverting resources from productive sectors of the economy to the financial sector, Romney’s path would likely slow growth.

The evidence would suggest that Romney can best be characterized as a “distributionalist” in Samuelson’s terms, although his plan to is to redistribute upward.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Okay, it’s not quite insider trading, but the NYT has an excellent article on how some hedge funds apparently get advance access to analysts’ reports on companies’ prospects.

Okay, it’s not quite insider trading, but the NYT has an excellent article on how some hedge funds apparently get advance access to analysts’ reports on companies’ prospects.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Wow, you just have to sit back in awe at something like this. Imagine the lead sports story the day after the Superbowl. It talks about who had a good day, the big plays, the big mistakes, and it never once mentions the score of the game. That is pretty much what the Post managed to do in a front page business section piece on the future of manufacturing in the United States.

If the Post noted the value of the dollar, which is the prime determinant of the relative cost of good produced in other countries and good produced in the United States, then it could have worked through some simple logic. The United States as a country will continue to consume manufactured goods. It is likely that thirty or forty years in the future we will still have cars, computer-like objects, houses made of manufactured materials, etc.

If we don’t manufacture these items here then we will have to import them. If we will import them, we will either have to export something else to pay for these imports or the rest of the world will have to give us manufactured goods for free. Something like the latter is happening now as China and other developing countries are buying up dollar denominated assets to keep up the value of the dollar against their currencies.

Essentially they are paying us to buy their stuff by making their products cheaper than they would otherwise be. This seems to be a useful development strategy at the moment, both because it helps to harness demand for their products and also because it allows them to accumulate massive amounts of dollar reserves which they believe are essential in an incompetently managed international financial system.

However, it is unlikely that situation will exist forever. China and other developing countries can pay their own people to buy their stuff, so it is not essential for them to indefinitely maintain huge export markets in the United States. Also, at some point they will presumably have enough reserves to get them through an inconceivable financial crisis.

This then raises the issue of how we will pay for the goods we import. While the popular line is “services,” this is mostly said by people who have not looked at the data. We would need an incredible a five-fold expansion of our surplus in services to even cover our current deficit. It would need to grow by a factor of ten if we lost all manufacturing in the U.S.

Furthermore, many trends in services point in the opposite direction. For example, we already have a large deficit with India in software services. This will certainly grow larger over time, and Indian software engineers will almost certainly drive us out of third countries as well.

We have a surplus on financial services, but this may slip if taxpayers got tired of subsidizing too big to fail Wall Street banks. One growing area of service exports is fees for royalties on patents and copyrights. This may grow if we have the economic and military power to impose more protectionist trade pacts (called “Free Trade Agreements” in Orwellian Washington newspeak), but that seems unlikely as countries like India are frequently insisting on paying free market prices for drugs.

The one rapidly growing area of surplus in services is tourism. Perhaps the future American workforce will be cleaning toilets and making beds for the rest of the world, since we will no longer be set up to manufacture goods.

Alternatively, the dollar might just fall so that the U.S. is again competitive in manufactured goods. That is the econ 101 story.

Wow, you just have to sit back in awe at something like this. Imagine the lead sports story the day after the Superbowl. It talks about who had a good day, the big plays, the big mistakes, and it never once mentions the score of the game. That is pretty much what the Post managed to do in a front page business section piece on the future of manufacturing in the United States.

If the Post noted the value of the dollar, which is the prime determinant of the relative cost of good produced in other countries and good produced in the United States, then it could have worked through some simple logic. The United States as a country will continue to consume manufactured goods. It is likely that thirty or forty years in the future we will still have cars, computer-like objects, houses made of manufactured materials, etc.

If we don’t manufacture these items here then we will have to import them. If we will import them, we will either have to export something else to pay for these imports or the rest of the world will have to give us manufactured goods for free. Something like the latter is happening now as China and other developing countries are buying up dollar denominated assets to keep up the value of the dollar against their currencies.

Essentially they are paying us to buy their stuff by making their products cheaper than they would otherwise be. This seems to be a useful development strategy at the moment, both because it helps to harness demand for their products and also because it allows them to accumulate massive amounts of dollar reserves which they believe are essential in an incompetently managed international financial system.

However, it is unlikely that situation will exist forever. China and other developing countries can pay their own people to buy their stuff, so it is not essential for them to indefinitely maintain huge export markets in the United States. Also, at some point they will presumably have enough reserves to get them through an inconceivable financial crisis.

This then raises the issue of how we will pay for the goods we import. While the popular line is “services,” this is mostly said by people who have not looked at the data. We would need an incredible a five-fold expansion of our surplus in services to even cover our current deficit. It would need to grow by a factor of ten if we lost all manufacturing in the U.S.

Furthermore, many trends in services point in the opposite direction. For example, we already have a large deficit with India in software services. This will certainly grow larger over time, and Indian software engineers will almost certainly drive us out of third countries as well.

We have a surplus on financial services, but this may slip if taxpayers got tired of subsidizing too big to fail Wall Street banks. One growing area of service exports is fees for royalties on patents and copyrights. This may grow if we have the economic and military power to impose more protectionist trade pacts (called “Free Trade Agreements” in Orwellian Washington newspeak), but that seems unlikely as countries like India are frequently insisting on paying free market prices for drugs.

The one rapidly growing area of surplus in services is tourism. Perhaps the future American workforce will be cleaning toilets and making beds for the rest of the world, since we will no longer be set up to manufacture goods.

Alternatively, the dollar might just fall so that the U.S. is again competitive in manufactured goods. That is the econ 101 story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión