Folks in Washington like to think that their silly dramas have much more impact on the world than they in fact do. The battle over extending the debt ceiling last year is a case in point, with its sequel, the 2013 Fiscal Cliff, providing another example.

Ezra Klein traced a slowdown in the economy last year to the uncertainty resulting from the battle over the debt ceiling. He tells readers:

“Early in the year, the recovery seemed to be proceeding smoothly. In February, the economy added 220,000 jobs. In March, it added 246,000 jobs. And in April, 251,000 jobs. But as summer approached, and as markets shuddered over the Republican threat to breach the debt ceiling, the economy sputtered. Between May and August, the nation never added more than 100,000 jobs a month. And then, in September, the month after the debt ceiling was resolved, the economy sped back up and added more than 200,000 jobs.”

He then goes on to give data on consumer confidence showing a fall in the months where consumers were supposed to be concerned about the debt ceiling. While this might sound as though it supports the case that concerns about the debt ceiling cratered the economy, the data on what people actually did (not what they said) indicates otherwise.

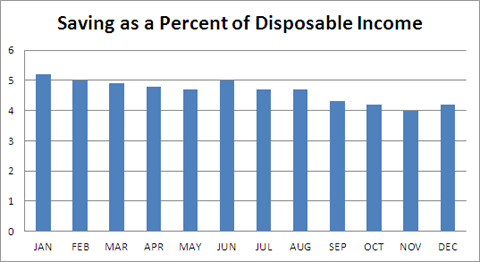

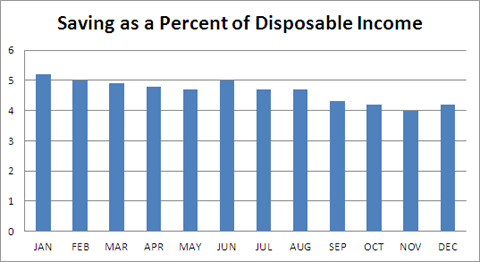

The chart below shows saving as a percent of disposable income. See the surge in the saving rate as the debt ceiling battle reached its crescendo in June and July? Me neither.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

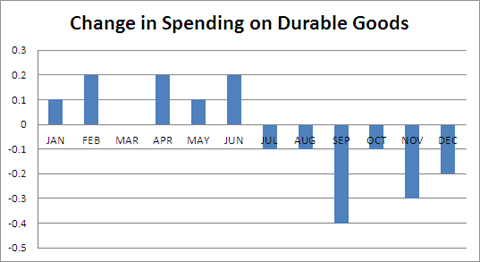

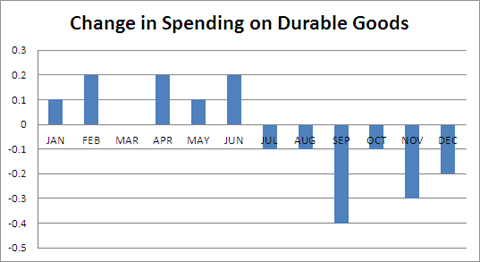

Suppose we look at the trend in spending on durable goods. These are big ticket items like cars and refrigerators, certainly not the sort of expenditure that worried consumers are likely to make if they could avoid it. Here we do see a falloff in July as people saw catastrophe about to hit, but durable good spending continues to fall after people got the all clear in early August. This one doesn’t seem to quite fit the worried consumer story either. (The data here are nominal, which is appropriate in this context since it reflects what people are willing to spend. It is unlikely that consumers are very aware of monthly price changes, especially in durable goods, since these will often be dominated by quality adjustments. The latter are calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and may not be entirely apparent to consumers at the time.)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

So if consumer spending didn’t fall through the floor what explains the dropoff in job creation? Typically there is some lag between GDP growth and job creation. GDP grew 2.5 percent in the third quarter and 2.3 percent in the fourth quarter. That fell to 0.4 percent in the first quarter, followed by 1.3 percent growth in the second quarter.

And why did GDP growth slow? Try the end of the stimulus. Government spending shrank at an annual rate of 2.8 in the fourth quarter of 2010, followed by drops of 5.9 percent in the first quarter and 0.9 percent in the second quarter. After being a boost to growth in the second half of 2009 and the first half of 2010, the government sector became a major drag on growth in the first half of 2011.

As I have argued elsewhere, consumer confidence measures largely reflect what people in the media are saying about the economy. They often have little to do with what consumers are doing.

Folks in Washington like to think that their silly dramas have much more impact on the world than they in fact do. The battle over extending the debt ceiling last year is a case in point, with its sequel, the 2013 Fiscal Cliff, providing another example.

Ezra Klein traced a slowdown in the economy last year to the uncertainty resulting from the battle over the debt ceiling. He tells readers:

“Early in the year, the recovery seemed to be proceeding smoothly. In February, the economy added 220,000 jobs. In March, it added 246,000 jobs. And in April, 251,000 jobs. But as summer approached, and as markets shuddered over the Republican threat to breach the debt ceiling, the economy sputtered. Between May and August, the nation never added more than 100,000 jobs a month. And then, in September, the month after the debt ceiling was resolved, the economy sped back up and added more than 200,000 jobs.”

He then goes on to give data on consumer confidence showing a fall in the months where consumers were supposed to be concerned about the debt ceiling. While this might sound as though it supports the case that concerns about the debt ceiling cratered the economy, the data on what people actually did (not what they said) indicates otherwise.

The chart below shows saving as a percent of disposable income. See the surge in the saving rate as the debt ceiling battle reached its crescendo in June and July? Me neither.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Suppose we look at the trend in spending on durable goods. These are big ticket items like cars and refrigerators, certainly not the sort of expenditure that worried consumers are likely to make if they could avoid it. Here we do see a falloff in July as people saw catastrophe about to hit, but durable good spending continues to fall after people got the all clear in early August. This one doesn’t seem to quite fit the worried consumer story either. (The data here are nominal, which is appropriate in this context since it reflects what people are willing to spend. It is unlikely that consumers are very aware of monthly price changes, especially in durable goods, since these will often be dominated by quality adjustments. The latter are calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and may not be entirely apparent to consumers at the time.)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

So if consumer spending didn’t fall through the floor what explains the dropoff in job creation? Typically there is some lag between GDP growth and job creation. GDP grew 2.5 percent in the third quarter and 2.3 percent in the fourth quarter. That fell to 0.4 percent in the first quarter, followed by 1.3 percent growth in the second quarter.

And why did GDP growth slow? Try the end of the stimulus. Government spending shrank at an annual rate of 2.8 in the fourth quarter of 2010, followed by drops of 5.9 percent in the first quarter and 0.9 percent in the second quarter. After being a boost to growth in the second half of 2009 and the first half of 2010, the government sector became a major drag on growth in the first half of 2011.

As I have argued elsewhere, consumer confidence measures largely reflect what people in the media are saying about the economy. They often have little to do with what consumers are doing.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That fact should have mentioned in a NYT article that touted an 11.2 percent jump in credit card debt in May. Much of this increase was offsetting a 4.9 percent decline reported for April.

That fact should have mentioned in a NYT article that touted an 11.2 percent jump in credit card debt in May. Much of this increase was offsetting a 4.9 percent decline reported for April.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post had a major front page article about how subprime loans threaten to undermine the prospects of African Americans for a decade. While African Americans do face discrimination in lending and are more likely to be given a subprime loan than whites with comparable credit and employment history, the real problem stemmed from the fact that so many bought homes in the middle of a housing bubble.

If someone bought a home at a bubble-inflated price that could be twice as much as its trend level, it would have a devastating impact on their finances, regardless of what type of mortgage they had. The big problem was that just about everyone in a position of authority was denying that there was a bubble and in fact helping to promote it.

For example, the Washington Post’s main, and often only, source in articles on the housing market was David Lereah, the chief economist at the National Association of Realtors and the author of the 2006 best seller, Why the Housing Boom Will not Bust and How You Can Profit from It.

Another popular source for major media outlets was the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University which felt the need to dismiss evidence of a housing bubble in its 2003 report on the state of the housing market. While many homeowners may have suffered as a result of taking the Harvard Center’s advice seriously, unfortunately the media does not consider its track record important. It continues to be used as a main source of expertise on the state of the housing market by major news outlets such as National Public Radio.

The Post had a major front page article about how subprime loans threaten to undermine the prospects of African Americans for a decade. While African Americans do face discrimination in lending and are more likely to be given a subprime loan than whites with comparable credit and employment history, the real problem stemmed from the fact that so many bought homes in the middle of a housing bubble.

If someone bought a home at a bubble-inflated price that could be twice as much as its trend level, it would have a devastating impact on their finances, regardless of what type of mortgage they had. The big problem was that just about everyone in a position of authority was denying that there was a bubble and in fact helping to promote it.

For example, the Washington Post’s main, and often only, source in articles on the housing market was David Lereah, the chief economist at the National Association of Realtors and the author of the 2006 best seller, Why the Housing Boom Will not Bust and How You Can Profit from It.

Another popular source for major media outlets was the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University which felt the need to dismiss evidence of a housing bubble in its 2003 report on the state of the housing market. While many homeowners may have suffered as a result of taking the Harvard Center’s advice seriously, unfortunately the media does not consider its track record important. It continues to be used as a main source of expertise on the state of the housing market by major news outlets such as National Public Radio.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

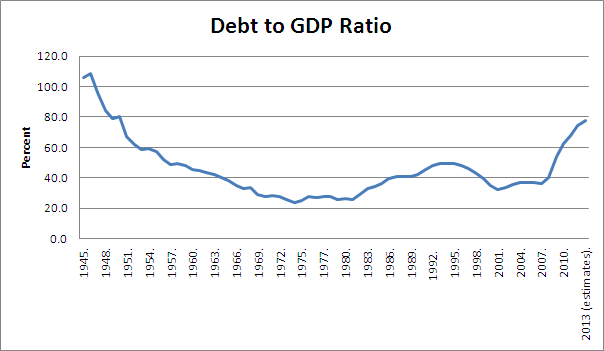

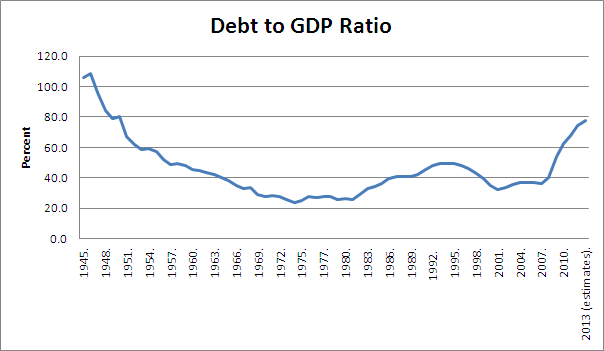

Robert Samuelson decided to blame the 60s again for the economic problems that we are suffering today. He argues that the decision by Kennedy to deliberately run higher deficits to boost the economy and to tolerate a higher rate of inflation gave us all of our current headaches. The former because we ended up with so much debt that we can’t now use large deficits to boost demand and the latter because it led to the runaway inflation of the 70s. It’s easy to show that both contentions are wrong.

First, the decision by Kennedy to run larger deficits did not lead to an increase in our debt to GDP ratio. In fact, this continued to decline through the 60s and 70s. The rise in the debt to GDP ratio was a Reagan era innovation. The ratio actually fell in the Clinton years, so for those keeping score on such things, rising debt to GDP ratios is largely a post-Reagan Republican president story.

Source: Economic Report of the President.

The second part of Samuelson’s argument is also wrong. There are relatively few instances where wealthy countries have seen large debt to GDP ratios. The claim that ratios above 90 percent slow growth confuses cause and effect. For example, Japan had a very low debt to GDP ratio before its stock and real estate bubbles burst in 1990. This collapse gave them both slow growth and a high debt to GDP ratio.

At the most basic level, the logic here is faulty. Government debt is an arbitrary category. If a government sold off assets or the right to tax (e.g. parking meters or patent monopolies) it can reduce its debt to GDP ratios in ways that could not plausibly increase growth. For this reason the idea that there is some systemic relationship between debt and growth is ridiculous on its face.

Finally, Samuelson’s complaint on inflation is badly mistaken. The United States would have benefitted enormously if it had a higher rate of inflation at the start of the downturn. If the underlying inflation rate had been 4.0 percent rather than 2.0 percent at the start of the downturn, a Federal Funds rate of zero would imply a negative real interest rate of -4.0 percent rather than -2.0 percent. This would have allowed monetary policy to provide a substantially larger boost to the economy.

Robert Samuelson decided to blame the 60s again for the economic problems that we are suffering today. He argues that the decision by Kennedy to deliberately run higher deficits to boost the economy and to tolerate a higher rate of inflation gave us all of our current headaches. The former because we ended up with so much debt that we can’t now use large deficits to boost demand and the latter because it led to the runaway inflation of the 70s. It’s easy to show that both contentions are wrong.

First, the decision by Kennedy to run larger deficits did not lead to an increase in our debt to GDP ratio. In fact, this continued to decline through the 60s and 70s. The rise in the debt to GDP ratio was a Reagan era innovation. The ratio actually fell in the Clinton years, so for those keeping score on such things, rising debt to GDP ratios is largely a post-Reagan Republican president story.

Source: Economic Report of the President.

The second part of Samuelson’s argument is also wrong. There are relatively few instances where wealthy countries have seen large debt to GDP ratios. The claim that ratios above 90 percent slow growth confuses cause and effect. For example, Japan had a very low debt to GDP ratio before its stock and real estate bubbles burst in 1990. This collapse gave them both slow growth and a high debt to GDP ratio.

At the most basic level, the logic here is faulty. Government debt is an arbitrary category. If a government sold off assets or the right to tax (e.g. parking meters or patent monopolies) it can reduce its debt to GDP ratios in ways that could not plausibly increase growth. For this reason the idea that there is some systemic relationship between debt and growth is ridiculous on its face.

Finally, Samuelson’s complaint on inflation is badly mistaken. The United States would have benefitted enormously if it had a higher rate of inflation at the start of the downturn. If the underlying inflation rate had been 4.0 percent rather than 2.0 percent at the start of the downturn, a Federal Funds rate of zero would imply a negative real interest rate of -4.0 percent rather than -2.0 percent. This would have allowed monetary policy to provide a substantially larger boost to the economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Okay folks, NPR should feel some real pain on this one. Some of you may recall last week when I beat up on NPR for presenting the views of Joe Olivo, a small business owner, on the Affordable Care Act (ACA). I pointed out that the piece the segment did not put Olivo’s complaints in any context so that listeners would have no way of assessing their validity.

It turned out that I was overly generous. Olivo was not a random small business owner who NPR happened to stumble upon. He is a person that the National Federal of Independent Businesses (NFIB), the lead plaintiff in the suit against the ACA, routinely sends out to speak to the media and to testify at public hearings. I discovered this from a blogpost at Balloon Juice.

One might have thought NPR would apologize for not properly identifying Mr. Olivo in its segment. However, if you thought that, you would be wrong.

Balloon Juice tells us that Mr. Olivo was back last night. He told All Things Considered listeners that a higher minimum wage is a really bad idea and would force him to lay off workers. Once again Mr. Olivo was presented as a random small business; his ties to the NFIB were not mentioned.

Come on folks, this is really Journalism 101. It’s fine to put Mr. Olivo on the air and let him give his story, but don’t present him as a random small business owner. The reason that you are talking to him is because the NFIB sent him to you. How could you not give this information to your audience?

If NPR keeps this up they should bill the series as Joe Olivo versus the Regulation Monster.

Okay folks, NPR should feel some real pain on this one. Some of you may recall last week when I beat up on NPR for presenting the views of Joe Olivo, a small business owner, on the Affordable Care Act (ACA). I pointed out that the piece the segment did not put Olivo’s complaints in any context so that listeners would have no way of assessing their validity.

It turned out that I was overly generous. Olivo was not a random small business owner who NPR happened to stumble upon. He is a person that the National Federal of Independent Businesses (NFIB), the lead plaintiff in the suit against the ACA, routinely sends out to speak to the media and to testify at public hearings. I discovered this from a blogpost at Balloon Juice.

One might have thought NPR would apologize for not properly identifying Mr. Olivo in its segment. However, if you thought that, you would be wrong.

Balloon Juice tells us that Mr. Olivo was back last night. He told All Things Considered listeners that a higher minimum wage is a really bad idea and would force him to lay off workers. Once again Mr. Olivo was presented as a random small business; his ties to the NFIB were not mentioned.

Come on folks, this is really Journalism 101. It’s fine to put Mr. Olivo on the air and let him give his story, but don’t present him as a random small business owner. The reason that you are talking to him is because the NFIB sent him to you. How could you not give this information to your audience?

If NPR keeps this up they should bill the series as Joe Olivo versus the Regulation Monster.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is what listeners to a segment that bemoaned the fact that China’s population might decline in the decades ahead undoubtedly concluded. The piece presented the views of people who saw the prospect of a smaller Chinese population as being a potential crisis, but not one word from anyone who indicated that it could potentially benefit both China and the world.

In terms of global warming and demand on resources more generally, the more people there are in China and the world as whole, the greater the pressure on the environment. In fact, if one (wrongly) assumes, as this piece implies, that more Chinese will make each person in China richer then the negative impact on the environment will be more than proportionate to the increase in population.

The other part of this piece is incredible absurd is the claim that China will somehow be strained paying for a growing population of retirees. The piece includes this segment:

“FENG [a Chinese demographer]: The magnitude of the challenge brought about by population aging is mind-boggling. China now has about 180 million elderly population. In less than 20 years, by 2030, that number is going to be 360 million. That’s going to be larger than the total population of the United States right now.

LANGFITT [the NPR reporter]: How is the country going to pay for that?

FENG: It’s a very scary situation.

LANGFITT: As the population ages, health care costs are expected to soar. And with couples having fewer kids, there will be far fewer workers to pay for that health care. Again, Wang Feng.

FENG: I think the harm has already been done. So even if China, say, stopped one-child policy tomorrow, this new birth would not become adult labor until 20 years from now.

LIANG: The situation is actually pretty gloomy, pretty bad, pretty urgent.”

Okay arithmetic fans, let’s see how China can pay for this. If we look at the IMF’s projections for China, we see that they expect per capita GDP to rise by 58 percent from 2011 to 2017, the last year for its projections. This is a per capita growth rate of 8 percent a year. Let’s hypothesize that this growth falls by 75 percent (a truly remarkable slowdown) to just 2 percent annually for the remaining 13 years to 2030. That would mean that China’s per capita GDP would be twice as high in 2030 as it was in 2011, in spite of the fact that the country had twice as many retirees.

The implication of this fact is that all the workers in the country could have living standards are at least twice as high as they are today and that all retirees can also have living standards that are higher than do current retirees. In fact, the story is likely to be even more favorable since China currently devotes almost half of its GDP to investment. This share would fall sharply as the growth rate declines leaving much more for consumption. (Actually, standard growth measures are likely to understate the benefits of a declining population since they will not pick up the gains from less use of common assets like streets, parks, and beaches.)

So arithmetic fans, there is no story whereby the Chinese will suffer because of plausible declines in the size of their population. You can take a deep breath and go back to enjoying your morning coffee.

That is what listeners to a segment that bemoaned the fact that China’s population might decline in the decades ahead undoubtedly concluded. The piece presented the views of people who saw the prospect of a smaller Chinese population as being a potential crisis, but not one word from anyone who indicated that it could potentially benefit both China and the world.

In terms of global warming and demand on resources more generally, the more people there are in China and the world as whole, the greater the pressure on the environment. In fact, if one (wrongly) assumes, as this piece implies, that more Chinese will make each person in China richer then the negative impact on the environment will be more than proportionate to the increase in population.

The other part of this piece is incredible absurd is the claim that China will somehow be strained paying for a growing population of retirees. The piece includes this segment:

“FENG [a Chinese demographer]: The magnitude of the challenge brought about by population aging is mind-boggling. China now has about 180 million elderly population. In less than 20 years, by 2030, that number is going to be 360 million. That’s going to be larger than the total population of the United States right now.

LANGFITT [the NPR reporter]: How is the country going to pay for that?

FENG: It’s a very scary situation.

LANGFITT: As the population ages, health care costs are expected to soar. And with couples having fewer kids, there will be far fewer workers to pay for that health care. Again, Wang Feng.

FENG: I think the harm has already been done. So even if China, say, stopped one-child policy tomorrow, this new birth would not become adult labor until 20 years from now.

LIANG: The situation is actually pretty gloomy, pretty bad, pretty urgent.”

Okay arithmetic fans, let’s see how China can pay for this. If we look at the IMF’s projections for China, we see that they expect per capita GDP to rise by 58 percent from 2011 to 2017, the last year for its projections. This is a per capita growth rate of 8 percent a year. Let’s hypothesize that this growth falls by 75 percent (a truly remarkable slowdown) to just 2 percent annually for the remaining 13 years to 2030. That would mean that China’s per capita GDP would be twice as high in 2030 as it was in 2011, in spite of the fact that the country had twice as many retirees.

The implication of this fact is that all the workers in the country could have living standards are at least twice as high as they are today and that all retirees can also have living standards that are higher than do current retirees. In fact, the story is likely to be even more favorable since China currently devotes almost half of its GDP to investment. This share would fall sharply as the growth rate declines leaving much more for consumption. (Actually, standard growth measures are likely to understate the benefits of a declining population since they will not pick up the gains from less use of common assets like streets, parks, and beaches.)

So arithmetic fans, there is no story whereby the Chinese will suffer because of plausible declines in the size of their population. You can take a deep breath and go back to enjoying your morning coffee.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post ran perhaps the best ever in-your-face article to the pundits who talk about the skills gap. Just to remind people, the skills gap story is that there all sorts of jobs that are going unfilled because employers just can’t find people with the necessary skills. In this story, the problem with the economy is not a lack of demand, the problem is that unemployed workers just don’t have the skills for the jobs that are available.

This one gets repeated endlessly in spite of the fact that there is no evidence for the story. There are no major sectors of the economy with large numbers of job openings relative to the number of unemployed workers, lengthening workweeks as firms seek to get more hours out of their existing workforce, or rapidly rising wages as firms try to bid away workers from other firms.

Lack of evidence never embarrassed a Washington pundit, but perhaps a compelling story will. A front page article in the Sunday Post reported that PhDs in chemistry and biology are having trouble getting jobs in their field. It reports that many are taking much lower paid positions outside of their field. Perhaps our pundits have a training program that will give these people the skills they need in today’s economy.

The Washington Post ran perhaps the best ever in-your-face article to the pundits who talk about the skills gap. Just to remind people, the skills gap story is that there all sorts of jobs that are going unfilled because employers just can’t find people with the necessary skills. In this story, the problem with the economy is not a lack of demand, the problem is that unemployed workers just don’t have the skills for the jobs that are available.

This one gets repeated endlessly in spite of the fact that there is no evidence for the story. There are no major sectors of the economy with large numbers of job openings relative to the number of unemployed workers, lengthening workweeks as firms seek to get more hours out of their existing workforce, or rapidly rising wages as firms try to bid away workers from other firms.

Lack of evidence never embarrassed a Washington pundit, but perhaps a compelling story will. A front page article in the Sunday Post reported that PhDs in chemistry and biology are having trouble getting jobs in their field. It reports that many are taking much lower paid positions outside of their field. Perhaps our pundits have a training program that will give these people the skills they need in today’s economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In the middle of Washington it can be difficult to get your hands on publicly available government documents. This is undoubtedly why George Will continues to misrepresent what President Obama’s economic advisers said about the stimulus package.

On This Week, ABC’s Sunday morning talk show, Will claimed that Obama’s advisers told him that if he did the stimulus that the unemployment rate would never get above 8.0 percent. Actually, if Will could find the publicly available document written in early January by Christine Romer, the head of the Council of Economic Advisers and Jared Bernstein, Vice-President Biden’s chief economist, he would know that they said the stimulus would create between 3-4 million jobs.

They expected that this rate of job creation would keep the unemployment rate from rising above 8.0 percent. While the stimulus package that got through Congress was somewhat smaller and less stimulatory (more tax cuts, less spending) than the package President Obama proposed, most independent analyses put the job impact in the 2-3 million range.

What Obama’s advisers got wrong in a big way was the severity of the downturn. The economy lost more than 3.1 million jobs in the first four months of 2009. This was a much sharper falloff than they had anticipated, as is clear from reading the document. The stimulus did create roughly the number of jobs projected, the problem was that we needed 10-12 million jobs, not 2-3 million.

President Obama’s team can and should be criticized for underestimating the severity of the downturn (like most of the economics profession). However, none of the evidence to date suggests that they were wrong about the effectiveness of the stimulus.

In the middle of Washington it can be difficult to get your hands on publicly available government documents. This is undoubtedly why George Will continues to misrepresent what President Obama’s economic advisers said about the stimulus package.

On This Week, ABC’s Sunday morning talk show, Will claimed that Obama’s advisers told him that if he did the stimulus that the unemployment rate would never get above 8.0 percent. Actually, if Will could find the publicly available document written in early January by Christine Romer, the head of the Council of Economic Advisers and Jared Bernstein, Vice-President Biden’s chief economist, he would know that they said the stimulus would create between 3-4 million jobs.

They expected that this rate of job creation would keep the unemployment rate from rising above 8.0 percent. While the stimulus package that got through Congress was somewhat smaller and less stimulatory (more tax cuts, less spending) than the package President Obama proposed, most independent analyses put the job impact in the 2-3 million range.

What Obama’s advisers got wrong in a big way was the severity of the downturn. The economy lost more than 3.1 million jobs in the first four months of 2009. This was a much sharper falloff than they had anticipated, as is clear from reading the document. The stimulus did create roughly the number of jobs projected, the problem was that we needed 10-12 million jobs, not 2-3 million.

President Obama’s team can and should be criticized for underestimating the severity of the downturn (like most of the economics profession). However, none of the evidence to date suggests that they were wrong about the effectiveness of the stimulus.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT piece on another possible round of court battles over the Affordable Care Act (ACA) told readers:

“White House officials have repeatedly underestimated opposition to the health care law. They predicted that public support for the law would grow as people learned more about it.”

This implies that people have learned about the ACA. That does not appear to be the case. According to poll conducted last fall by Kaiser only 45 percent of people knew that the ACA did not create panels that would make decisions about end of life care for Medicare patients. Only 25 percent knew that the bill did not require firms with less than 50 employees to provide insurance for their workers. Only 42 percent knew that the bill does not provide insurance to undocumented workers.

In short, the evidence suggests that the media has done a very poor job in educating the public about the specifics of the plan. (Michelle Rhee would fire all the reporters immediately.) We do not know how people will respond if they learn more about the ACA because this far they have not.

A NYT piece on another possible round of court battles over the Affordable Care Act (ACA) told readers:

“White House officials have repeatedly underestimated opposition to the health care law. They predicted that public support for the law would grow as people learned more about it.”

This implies that people have learned about the ACA. That does not appear to be the case. According to poll conducted last fall by Kaiser only 45 percent of people knew that the ACA did not create panels that would make decisions about end of life care for Medicare patients. Only 25 percent knew that the bill did not require firms with less than 50 employees to provide insurance for their workers. Only 42 percent knew that the bill does not provide insurance to undocumented workers.

In short, the evidence suggests that the media has done a very poor job in educating the public about the specifics of the plan. (Michelle Rhee would fire all the reporters immediately.) We do not know how people will respond if they learn more about the ACA because this far they have not.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión