That is what he told us in his New York Times column that was ostensibly about out of control Social Security and Medicare spending. Emmanuel begins by telling readers:

“If nothing is done about entitlement spending, and if our current tax breaks continue, then by 2025, tax revenue will be able to pay for Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, interest on the debt and nothing else.”

There are two big problems with this story. First there is the old trick of conflating Social Security with Medicare and Medicaid. This is a great trick for those who want to deceive people into believing the budget problem is primarily a demographic story. However, it is highly misleading. The retirement of baby boomers is projected to increase Social Security spending by 0.9 percentage points of GDP or roughly 20 percent between now and 2025.

By comparison, military spending increased by more than 1 percentage point of GDP between 2000 and 2005. In other words, the projected increase in Social Security spending over the next 13 years is relatively modest and easily affordable. It also is fully covered by projected Social Security revenue and assets in the trust fund.

The projected increase in health care spending is considerably larger, however this depends on using the Congressional Budget Office’s “alternative fiscal scenario” rather than the baseline projection. The difference is that the baseline projection assumes substantial cost controls that were in the Affordable Care Act. These cost controls, if left in place, would substantially reduce the rate of growth of Medicare costs.

This point is important for two reasons. First it shows directly that the issue is not primarily one of demographics but rather one of exploding health care costs. Second, it is in principle possible to control these costs if the political power of health care providers can be held in check.

Per person health care costs in the United States are hugely out of line with costs anywhere else in the world. If our costs were comparable to those in any other wealthy country we would be looking at long-term budget surpluses rather than deficits. If it is too difficult politically to directly fix the U.S. system we could achieve enormous savings simply by allowing more trade in health care services. We will only see the explosive growth in health care costs described in the alternative fiscal scenario if health care providers and insurance companies are both powerful enough to prevent domestic reform and to maintain protectionist barriers that prevent people in the United States from taking advantage of lower cost care elsewhere.

It is also worth noting that Emanuel’s proposed cuts in these programs would hit people with average lifetime earnings of $40,000 and above. It might make more sense to place more burden on people earning $250,000 and above by raising their taxes.

That is what he told us in his New York Times column that was ostensibly about out of control Social Security and Medicare spending. Emmanuel begins by telling readers:

“If nothing is done about entitlement spending, and if our current tax breaks continue, then by 2025, tax revenue will be able to pay for Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, interest on the debt and nothing else.”

There are two big problems with this story. First there is the old trick of conflating Social Security with Medicare and Medicaid. This is a great trick for those who want to deceive people into believing the budget problem is primarily a demographic story. However, it is highly misleading. The retirement of baby boomers is projected to increase Social Security spending by 0.9 percentage points of GDP or roughly 20 percent between now and 2025.

By comparison, military spending increased by more than 1 percentage point of GDP between 2000 and 2005. In other words, the projected increase in Social Security spending over the next 13 years is relatively modest and easily affordable. It also is fully covered by projected Social Security revenue and assets in the trust fund.

The projected increase in health care spending is considerably larger, however this depends on using the Congressional Budget Office’s “alternative fiscal scenario” rather than the baseline projection. The difference is that the baseline projection assumes substantial cost controls that were in the Affordable Care Act. These cost controls, if left in place, would substantially reduce the rate of growth of Medicare costs.

This point is important for two reasons. First it shows directly that the issue is not primarily one of demographics but rather one of exploding health care costs. Second, it is in principle possible to control these costs if the political power of health care providers can be held in check.

Per person health care costs in the United States are hugely out of line with costs anywhere else in the world. If our costs were comparable to those in any other wealthy country we would be looking at long-term budget surpluses rather than deficits. If it is too difficult politically to directly fix the U.S. system we could achieve enormous savings simply by allowing more trade in health care services. We will only see the explosive growth in health care costs described in the alternative fiscal scenario if health care providers and insurance companies are both powerful enough to prevent domestic reform and to maintain protectionist barriers that prevent people in the United States from taking advantage of lower cost care elsewhere.

It is also worth noting that Emanuel’s proposed cuts in these programs would hit people with average lifetime earnings of $40,000 and above. It might make more sense to place more burden on people earning $250,000 and above by raising their taxes.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In a blogpost discussing the push by many groups to get a financial transactions tax the Post told readers:

“The White House believes it would be easy to evade, could hamper economic growth, and might make markets more volatile, not less so. Instead, Obama has proposed a new ‘financial crisis responsibility fee’ on big banks, which would raise about $61 billion. “

While it is not clear how the Post knows what the White House really believes, what we know is that financial transactions taxes are apparently not that easy to evade. The tax in the UK, which applies only to stocks (not derivative instruments like credit default swaps, options, and futures) raises between 0.2 and 0.3 percent of GDP annually. This would be between $30-$45 billion a year in the United States. Unless we assume that the Obama administration thinks our tax collectors are much less competent than those in the UK, then they presumably do not really “believe” that the tax will be easy to evade.

The reference to economic growth refers to outdated research by the European Commission (EC). The most recent study by the EC shows that a tax would lead to somewhat more rapid growth if the money was used either to reduce other taxes or finance public investment.

If the White House has any evidence that the tax would increase volatility they are keeping it secret from the world. The tax would simply raise transactions costs back to where they were 10-15 years ago. Financial markets were not obviously more volatile in 1995 than they are today.

Finally, the “financial crisis responsibility fee” proposed by the Obama administration would raise an order of magnitude less tax revenue than the financial transactions taxes of the size generally being proposed. The Obama administration surely understands that they are pushing a tax that will have much less impact on the financial sector and will raise much less revenue than a financial transactions taxes.

The Post does not know what the White House “believes” about financial transactions taxes. It knows what it says about financial transactions taxes. While what it says may reflect what it believes, it may also reflect the fact that the administration is hoping to raise money for its re-election campaign from Wall Street. Also, many officials in the administration may hope to work on Wall Street after leaving the administration. These are the facts that we know.

In a blogpost discussing the push by many groups to get a financial transactions tax the Post told readers:

“The White House believes it would be easy to evade, could hamper economic growth, and might make markets more volatile, not less so. Instead, Obama has proposed a new ‘financial crisis responsibility fee’ on big banks, which would raise about $61 billion. “

While it is not clear how the Post knows what the White House really believes, what we know is that financial transactions taxes are apparently not that easy to evade. The tax in the UK, which applies only to stocks (not derivative instruments like credit default swaps, options, and futures) raises between 0.2 and 0.3 percent of GDP annually. This would be between $30-$45 billion a year in the United States. Unless we assume that the Obama administration thinks our tax collectors are much less competent than those in the UK, then they presumably do not really “believe” that the tax will be easy to evade.

The reference to economic growth refers to outdated research by the European Commission (EC). The most recent study by the EC shows that a tax would lead to somewhat more rapid growth if the money was used either to reduce other taxes or finance public investment.

If the White House has any evidence that the tax would increase volatility they are keeping it secret from the world. The tax would simply raise transactions costs back to where they were 10-15 years ago. Financial markets were not obviously more volatile in 1995 than they are today.

Finally, the “financial crisis responsibility fee” proposed by the Obama administration would raise an order of magnitude less tax revenue than the financial transactions taxes of the size generally being proposed. The Obama administration surely understands that they are pushing a tax that will have much less impact on the financial sector and will raise much less revenue than a financial transactions taxes.

The Post does not know what the White House “believes” about financial transactions taxes. It knows what it says about financial transactions taxes. While what it says may reflect what it believes, it may also reflect the fact that the administration is hoping to raise money for its re-election campaign from Wall Street. Also, many officials in the administration may hope to work on Wall Street after leaving the administration. These are the facts that we know.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I hate to be picky, but this seems like a rather bizarre term to include in this Washington Post piece on the G-8 meeting on Saturday. The full sentence is:

“Obama, who has pushed for additional fiscal stimulus in the United States, said the new agreement affirmed the course his administration pursued during the financial recession at home.”

It is difficult to see what is added by including the word “financial.” The point is that we are still suffering from the effects of the recession that officially began in December 2007. If the concern is that the recession officially ended in June of 2009 so that it is improper to refer to the current period as a “recession,” then the word “downturn” should do the trick.

It is hard to see what including “financial” in the description does except confuse people. We have a downturn in the real economy, not just a few problems in the financial sector.

I hate to be picky, but this seems like a rather bizarre term to include in this Washington Post piece on the G-8 meeting on Saturday. The full sentence is:

“Obama, who has pushed for additional fiscal stimulus in the United States, said the new agreement affirmed the course his administration pursued during the financial recession at home.”

It is difficult to see what is added by including the word “financial.” The point is that we are still suffering from the effects of the recession that officially began in December 2007. If the concern is that the recession officially ended in June of 2009 so that it is improper to refer to the current period as a “recession,” then the word “downturn” should do the trick.

It is hard to see what including “financial” in the description does except confuse people. We have a downturn in the real economy, not just a few problems in the financial sector.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It wasn’t quite that bad, but it was pretty close. A front page Washington Post story told readers that:

“The overpayments, discovered in an inspector general’s audit, boosted the annual pay of some of the employees [some of four employees] by as much as $64,000.”

I will be the last person to defend people ripping off the government, but we do need some context here. Assuming a worst case scenario, the amount of overpayments to these government employees amounted to less than $200,000 a year. That comes to less than 0.000006 percent of federal spending. Is this worth a front page story in the Washington Post?

My guess is that if we looked at any major defense contractor (e.g. Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrup Grumman) we could probably find overpayments that are at least ten times as large with a careful examination of every major contract. Such stories can rarely be found on the front page of the Washington Post.

Readers might ask why the Post thinks it is so important to highlight overpayments to a small number of government employees that, for all practical purposes, have zero consequence for the budget while neglecting much larger abuses by government contractors.

It wasn’t quite that bad, but it was pretty close. A front page Washington Post story told readers that:

“The overpayments, discovered in an inspector general’s audit, boosted the annual pay of some of the employees [some of four employees] by as much as $64,000.”

I will be the last person to defend people ripping off the government, but we do need some context here. Assuming a worst case scenario, the amount of overpayments to these government employees amounted to less than $200,000 a year. That comes to less than 0.000006 percent of federal spending. Is this worth a front page story in the Washington Post?

My guess is that if we looked at any major defense contractor (e.g. Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrup Grumman) we could probably find overpayments that are at least ten times as large with a careful examination of every major contract. Such stories can rarely be found on the front page of the Washington Post.

Readers might ask why the Post thinks it is so important to highlight overpayments to a small number of government employees that, for all practical purposes, have zero consequence for the budget while neglecting much larger abuses by government contractors.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A front page Washington Post article discussed the choice that people in Greece must consider, of either staying in the euro and facing perhaps a decade or more of double-digit unemployment, or leaving the euro and facing the uncertainty of going back to its own currency. The Post misrepresented the tradeoffs involved when it presented the views of Nikas Niakaros, an exporter of feta cheese:

“But instead, Niakaros is sweating bullets. Like many Greek exporters, he depends on a supply chain of imported goods — from specially enriched feed for his sheep to the natural gas used to power his factory — that would spike in price if Greece left the euro. Business loans, meanwhile, would be far more expensive and harder to get. Add unpredictable jumps in inflation as happened during the era of the drachma, and, Niakaros said, the cost benefits of a cheaper currency would disappear.”

While this may accurately present Mr. Niakaros’ assessment, he happens to be wrong. If the Greek currency falls by 20 percent relative to the euro, this could mean that the price that Mr. Niakaros pays for his imported inputs will rise by 20 percent. It should also mean that the price he can sell his feta will rise by roughly 20 percent measured in the new Greek currency. However, the amount that he pays in wages to Greek workers and rent for his property will almost certainly not rise by 20 percent. This should mean that he will hugely increase his profits on the portion of his output that he exports.

While it is interesting to get the views of the people of Greece on how they would be affected by an exit from the euro, the Post should be careful not to present inaccurate information unchallenged. Most of its readers probably will not know that Mr. Niakoros’s assessment of the situation is wrong.

A front page Washington Post article discussed the choice that people in Greece must consider, of either staying in the euro and facing perhaps a decade or more of double-digit unemployment, or leaving the euro and facing the uncertainty of going back to its own currency. The Post misrepresented the tradeoffs involved when it presented the views of Nikas Niakaros, an exporter of feta cheese:

“But instead, Niakaros is sweating bullets. Like many Greek exporters, he depends on a supply chain of imported goods — from specially enriched feed for his sheep to the natural gas used to power his factory — that would spike in price if Greece left the euro. Business loans, meanwhile, would be far more expensive and harder to get. Add unpredictable jumps in inflation as happened during the era of the drachma, and, Niakaros said, the cost benefits of a cheaper currency would disappear.”

While this may accurately present Mr. Niakaros’ assessment, he happens to be wrong. If the Greek currency falls by 20 percent relative to the euro, this could mean that the price that Mr. Niakaros pays for his imported inputs will rise by 20 percent. It should also mean that the price he can sell his feta will rise by roughly 20 percent measured in the new Greek currency. However, the amount that he pays in wages to Greek workers and rent for his property will almost certainly not rise by 20 percent. This should mean that he will hugely increase his profits on the portion of his output that he exports.

While it is interesting to get the views of the people of Greece on how they would be affected by an exit from the euro, the Post should be careful not to present inaccurate information unchallenged. Most of its readers probably will not know that Mr. Niakoros’s assessment of the situation is wrong.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The methodology that the Treasury Department is using when claiming that we made money on the TARP would imply that the government could make money by issuing a 30-year mortgage at 1.0 percent interest to every homeowners in the country. The vast majority of these mortgages would of course be paid off with interest, therefore the taxpayers would come out ahead.

This is ridiculous accounting, as Gretchen Morgenson points out in her column today. There is an opportunity cost to this money and if that is not taken into account, there is no way to say whether this lending is profitable. In the case of the TARP and related Fed lending programs, financial institutions were able to borrow trillions of dollars at far below market interest rates.

These programs may have been justified given the situation in financial markets at the time, however it is ridiculous to say that we made a profit on the lending based on the fact that most of the money was repaid with interest just as it would be ridiculous to claim a profit on 1.0 percent 30-year fixed rate mortgages issued by the government.

In the FWIW category, anyone saying that we would have had a second Great Depression absent this lending should be immediately ignored. The first Great Depression was caused by 10 years of inadequate policy response, not just the mistakes made at the onset. There was nothing that we did or did not do in 2008-2009 that would have necessitated a decade of incompetent policy.

Argentina was able to recover from a full-fledged financial collapse in less than 18 months. There is no reason to believe that Ben Bernanke and other leading policy makers are very much less competent than the people determining economic policy in Argentina.

The methodology that the Treasury Department is using when claiming that we made money on the TARP would imply that the government could make money by issuing a 30-year mortgage at 1.0 percent interest to every homeowners in the country. The vast majority of these mortgages would of course be paid off with interest, therefore the taxpayers would come out ahead.

This is ridiculous accounting, as Gretchen Morgenson points out in her column today. There is an opportunity cost to this money and if that is not taken into account, there is no way to say whether this lending is profitable. In the case of the TARP and related Fed lending programs, financial institutions were able to borrow trillions of dollars at far below market interest rates.

These programs may have been justified given the situation in financial markets at the time, however it is ridiculous to say that we made a profit on the lending based on the fact that most of the money was repaid with interest just as it would be ridiculous to claim a profit on 1.0 percent 30-year fixed rate mortgages issued by the government.

In the FWIW category, anyone saying that we would have had a second Great Depression absent this lending should be immediately ignored. The first Great Depression was caused by 10 years of inadequate policy response, not just the mistakes made at the onset. There was nothing that we did or did not do in 2008-2009 that would have necessitated a decade of incompetent policy.

Argentina was able to recover from a full-fledged financial collapse in less than 18 months. There is no reason to believe that Ben Bernanke and other leading policy makers are very much less competent than the people determining economic policy in Argentina.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

David Brooks lectures us this morning on the need to have a balance between self-doubt and self-confidence.

“Western democratic systems were based on a balance between self-doubt and self-confidence. They worked because there were structures that protected the voters from themselves and the rulers from themselves. Once people lost a sense of their own weakness, the self-doubt went away and the chastening structures were overwhelmed.”

According to Brooks:

“In Europe, workers across the Continent want great lifestyles without long work hours. They want dynamic capitalism but also personal security. European welfare states go broke trying to deliver these impossibilities.”

The problem of course is that these are not impossibilities. Like the United States, Europe’s economies increase their productivity every year. Higher productivity growth means that people can enjoy higher living standards. There is absolutely nothing impossible about having dynamic capitalism along with security and shorter work hours. In fact, the latter is arguably the purpose of the former. In the European welfare states the economies were structured in a way that led more of the gains from this growth to be broadly shared as opposed to the United States, where the economy was structured to distribute most of the gains to those at the top.

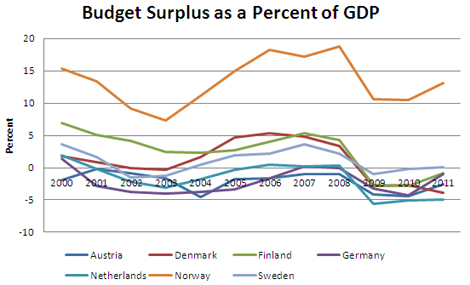

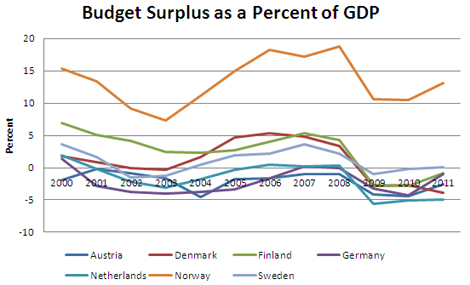

And the European welfare states were not going broke. Until the crisis the most generous welfare states in northern Europe were either running budget surpluses or relatively small sustainable deficits. (Yes, these are surpluses — positive is larger.) Unlike the United States these countries also had trade surpluses or small deficits.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

In short, the underlying claim of Brooks’ eloquent homily on self-doubt and self-confidence is not true. If Brooks had a bit more self-doubt perhaps he would have bothered to look at the data or consult someone who knew the data before devoting valuable space on the NYT oped page to making a point that is not valid.

David Brooks lectures us this morning on the need to have a balance between self-doubt and self-confidence.

“Western democratic systems were based on a balance between self-doubt and self-confidence. They worked because there were structures that protected the voters from themselves and the rulers from themselves. Once people lost a sense of their own weakness, the self-doubt went away and the chastening structures were overwhelmed.”

According to Brooks:

“In Europe, workers across the Continent want great lifestyles without long work hours. They want dynamic capitalism but also personal security. European welfare states go broke trying to deliver these impossibilities.”

The problem of course is that these are not impossibilities. Like the United States, Europe’s economies increase their productivity every year. Higher productivity growth means that people can enjoy higher living standards. There is absolutely nothing impossible about having dynamic capitalism along with security and shorter work hours. In fact, the latter is arguably the purpose of the former. In the European welfare states the economies were structured in a way that led more of the gains from this growth to be broadly shared as opposed to the United States, where the economy was structured to distribute most of the gains to those at the top.

And the European welfare states were not going broke. Until the crisis the most generous welfare states in northern Europe were either running budget surpluses or relatively small sustainable deficits. (Yes, these are surpluses — positive is larger.) Unlike the United States these countries also had trade surpluses or small deficits.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

In short, the underlying claim of Brooks’ eloquent homily on self-doubt and self-confidence is not true. If Brooks had a bit more self-doubt perhaps he would have bothered to look at the data or consult someone who knew the data before devoting valuable space on the NYT oped page to making a point that is not valid.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión