The NYT’s truth vigilante was apparently sleeping when the paper printed without comment the Motion Picture Industry’s claim that the country lost 100,000 jobs due to on-line “piracy.” The truth vigilante would have pointed out that the money that consumers do not spend paying for copyright-protected work is available to be spent in other areas. The payments for copyright protected items have the same effect on the economy as a tax, they pull money out of the economy. While some of this may end up supporting more creative work, it is likely that most would simply end up as greater profits for the industry and larger royalty checks for a small number of highly paid performers.

By contrast, the requirements of the Stop On-Line Piracy Act are a good example of “job-killing” government regulation. They would impose additional costs on intermediaries which would be passed on to consumers and slow technological progress.

It is incorrect to use the term “piracy” in this discussion, even though the entertainment industry has paid lots of money to get it accepted. The items in question may not be in violation of the law in the countries where they are posted. In that case, the posting cannot properly be termed “piracy.” It would be more accurate to use the neutral term “unauthorized copy.”

The NYT’s truth vigilante was apparently sleeping when the paper printed without comment the Motion Picture Industry’s claim that the country lost 100,000 jobs due to on-line “piracy.” The truth vigilante would have pointed out that the money that consumers do not spend paying for copyright-protected work is available to be spent in other areas. The payments for copyright protected items have the same effect on the economy as a tax, they pull money out of the economy. While some of this may end up supporting more creative work, it is likely that most would simply end up as greater profits for the industry and larger royalty checks for a small number of highly paid performers.

By contrast, the requirements of the Stop On-Line Piracy Act are a good example of “job-killing” government regulation. They would impose additional costs on intermediaries which would be passed on to consumers and slow technological progress.

It is incorrect to use the term “piracy” in this discussion, even though the entertainment industry has paid lots of money to get it accepted. The items in question may not be in violation of the law in the countries where they are posted. In that case, the posting cannot properly be termed “piracy.” It would be more accurate to use the neutral term “unauthorized copy.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT reported on a Supreme Court ruling that retroactively granted copyright protection to foreign works that had previously been in the public domain. As Justice Breyer argued in dissent, this action appears to exceed the constitutional authority given to Congress, which ties copyrights to a specific public policy goal: “to promote the progress of science and useful arts.”

In this case, since the copyright is explicitly being applied retroactively to work that has already been produced, it cannot possibly be viewed as providing incentive to develop the material. This means that the government is assigning a monopoly to items that were formerly in the public domain and available at no cost. It is prepared to arrest people and throw them in jail if they don’t respect this government granted monopoly.

Given the large number of political groups complaining about activist judges and big government intervention into people’s lives, it would have been useful to include some of their views about the court’s action. Perhaps this can be addressed in a follow-up piece.

The NYT reported on a Supreme Court ruling that retroactively granted copyright protection to foreign works that had previously been in the public domain. As Justice Breyer argued in dissent, this action appears to exceed the constitutional authority given to Congress, which ties copyrights to a specific public policy goal: “to promote the progress of science and useful arts.”

In this case, since the copyright is explicitly being applied retroactively to work that has already been produced, it cannot possibly be viewed as providing incentive to develop the material. This means that the government is assigning a monopoly to items that were formerly in the public domain and available at no cost. It is prepared to arrest people and throw them in jail if they don’t respect this government granted monopoly.

Given the large number of political groups complaining about activist judges and big government intervention into people’s lives, it would have been useful to include some of their views about the court’s action. Perhaps this can be addressed in a follow-up piece.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Readers don’t expect much from the Washington Post when it comes to economic issues, so it is notable when an opinion column gets issues at least half right. In that vein, Fareed Zakaria’s piece today noting the ways in which Germany seems to be outperforming the U.S. is worthy of attention.

First, let’s note a couple of the things he gets wrong. Zakaria touts the growth in exports under President Obama, claiming that they have been growing at a 16 percent annual rate. He tells readers that this “means that U.S. exports should double earlier than 2014, the goal President Obama set in 2009.”

Apparently, Zakaria is looking at the nominal value of exports. The real value of exports has increased by a total of just 12.9 percent since the fourth quarter of 2008. At this pace, we won’t see exports double until around 2023. Perhaps Obama meant that he would reach his goal primarily through higher prices, but usually presidents don’t want to boast about higher inflation on their watch.

The second point is that no serious person (okay, this is the Washington Post opinion page) would value exports in isolation. Net exports, exports minus imports, create jobs, not exports alone. If we export car parts to be assembled into a car in Mexico, it certainly does not create more jobs in the United States than when the car was assembled in the United States.

Because imports have exceeded exports by a huge amount over the last 15 years (i.e. we have large trade deficits) the United States has lost millions of jobs. The trade deficit has only declined by about half a percentage point of GDP during the Obama years. So in this sense, trade has contributed little to growth and jobs.

Zakaria also errs in his portrayal of the investment record on Clinton, Bush, and Obama. He tells readers:

“From 2001 to 2007, investment in equipment and software — the kinds of investments that boost productivity and create good jobs — declined 15 percent as a share of gross domestic product. … In contrast, the current recovery, while anemic in terms of number of jobs created, is more broad-based and more durable. Business investment is rising, having boomed 18 percent since the end of 2009.”

Actually, much of the investment in equipment in software at the end of the Clinton years was driven by the bubble in tech stocks. It was wasted establishing operations like Pets.com and other companies that quickly ended up in the dustbin of startup history. While this spending created jobs in the same way that paying people to dig holes and fill them up again will create jobs, it did not boost productivity.

Productivity growth over the Bush years averaged 2.2 percent annually. In the pre-recession period it averaged 2.7 percent. This compares to a 2.0 percent annual rate for the Clinton years taken as a whole and a 2.7 percent rate for the period following the beginning of the productivity speedup in 1995. In other words, there is little basis for saying that the falloff in investment in the Bush years harmed productivity growth.

On the other hand, the boom in investment during the Obama years touted by Zakaria is simply making up for the collapse of investment during the downturn. This is a normal pattern following a recession. Even with the Zakaria boom, equipment and software investment have still not risen back to its pre-recession share of GDP.

Now for the part that Zakaria gets right; Germany has done well because of its different attitude towards its workers. It is German government policy to try to persuade employers to keep workers on their payroll even during a downturn through policies like work sharing. This ensures that the workers continue to stay in the workforce and upgrade their skills. By contrast, many workers in the United States face long-term unemployment and some may never work again.

Germany has been so successful with this policy that its unemployment rate is now 1.6 percentage points lower than it was before the recession began. That is in spite of the fact that its GDP growth has been no better than GDP growth in the United States. The difference has been its labor force policy.

Zakaria notes the importance of the German experience and, citing a paper from the Brookings Institution, holds it up as a model for the United States. At CEPR we are always glad to see Brookings follow our lead so that the Post can write about a topic of importance.

Readers don’t expect much from the Washington Post when it comes to economic issues, so it is notable when an opinion column gets issues at least half right. In that vein, Fareed Zakaria’s piece today noting the ways in which Germany seems to be outperforming the U.S. is worthy of attention.

First, let’s note a couple of the things he gets wrong. Zakaria touts the growth in exports under President Obama, claiming that they have been growing at a 16 percent annual rate. He tells readers that this “means that U.S. exports should double earlier than 2014, the goal President Obama set in 2009.”

Apparently, Zakaria is looking at the nominal value of exports. The real value of exports has increased by a total of just 12.9 percent since the fourth quarter of 2008. At this pace, we won’t see exports double until around 2023. Perhaps Obama meant that he would reach his goal primarily through higher prices, but usually presidents don’t want to boast about higher inflation on their watch.

The second point is that no serious person (okay, this is the Washington Post opinion page) would value exports in isolation. Net exports, exports minus imports, create jobs, not exports alone. If we export car parts to be assembled into a car in Mexico, it certainly does not create more jobs in the United States than when the car was assembled in the United States.

Because imports have exceeded exports by a huge amount over the last 15 years (i.e. we have large trade deficits) the United States has lost millions of jobs. The trade deficit has only declined by about half a percentage point of GDP during the Obama years. So in this sense, trade has contributed little to growth and jobs.

Zakaria also errs in his portrayal of the investment record on Clinton, Bush, and Obama. He tells readers:

“From 2001 to 2007, investment in equipment and software — the kinds of investments that boost productivity and create good jobs — declined 15 percent as a share of gross domestic product. … In contrast, the current recovery, while anemic in terms of number of jobs created, is more broad-based and more durable. Business investment is rising, having boomed 18 percent since the end of 2009.”

Actually, much of the investment in equipment in software at the end of the Clinton years was driven by the bubble in tech stocks. It was wasted establishing operations like Pets.com and other companies that quickly ended up in the dustbin of startup history. While this spending created jobs in the same way that paying people to dig holes and fill them up again will create jobs, it did not boost productivity.

Productivity growth over the Bush years averaged 2.2 percent annually. In the pre-recession period it averaged 2.7 percent. This compares to a 2.0 percent annual rate for the Clinton years taken as a whole and a 2.7 percent rate for the period following the beginning of the productivity speedup in 1995. In other words, there is little basis for saying that the falloff in investment in the Bush years harmed productivity growth.

On the other hand, the boom in investment during the Obama years touted by Zakaria is simply making up for the collapse of investment during the downturn. This is a normal pattern following a recession. Even with the Zakaria boom, equipment and software investment have still not risen back to its pre-recession share of GDP.

Now for the part that Zakaria gets right; Germany has done well because of its different attitude towards its workers. It is German government policy to try to persuade employers to keep workers on their payroll even during a downturn through policies like work sharing. This ensures that the workers continue to stay in the workforce and upgrade their skills. By contrast, many workers in the United States face long-term unemployment and some may never work again.

Germany has been so successful with this policy that its unemployment rate is now 1.6 percentage points lower than it was before the recession began. That is in spite of the fact that its GDP growth has been no better than GDP growth in the United States. The difference has been its labor force policy.

Zakaria notes the importance of the German experience and, citing a paper from the Brookings Institution, holds it up as a model for the United States. At CEPR we are always glad to see Brookings follow our lead so that the Post can write about a topic of importance.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Wall Street Journal wants us to be worried that we will be paying less for our shoes, clothes, and engineering services. Actually, they only want us to be concerned about the last of these three, although it never tells us why.

It had an article the point of which is to warn readers that engineering is increasingly being outsourced to Asia. This may be bad news to people who hope to work in engineering, but for the rest of us, it means cheaper products, just as buying clothes and shoes manufactured abroad meant cheaper products.

The outsourcing of manufactured jobs is of course bad news for manufacturing workers and there are many more people who either work in manufacturing or could potentially if the jobs were there. In other words, the WSJ would have a much more compelling case if it warned us about the risk of losing jobs in clothing and shoe making to Asia than it does with engineering. For the overwhelming majority of people in the United States, this should mean an improvement in living standards.

The Wall Street Journal wants us to be worried that we will be paying less for our shoes, clothes, and engineering services. Actually, they only want us to be concerned about the last of these three, although it never tells us why.

It had an article the point of which is to warn readers that engineering is increasingly being outsourced to Asia. This may be bad news to people who hope to work in engineering, but for the rest of us, it means cheaper products, just as buying clothes and shoes manufactured abroad meant cheaper products.

The outsourcing of manufactured jobs is of course bad news for manufacturing workers and there are many more people who either work in manufacturing or could potentially if the jobs were there. In other words, the WSJ would have a much more compelling case if it warned us about the risk of losing jobs in clothing and shoe making to Asia than it does with engineering. For the overwhelming majority of people in the United States, this should mean an improvement in living standards.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Wall Street Journal had a bizarre article about capital investment and robotics to explain the slow job growth in this recovery. There actually is a much simpler explanation, it’s called “slow growth.”

Productivity growth has averaged close to 2.5 percent since 1995. That means the economy must grow at a 2.5 percent rate just to keep labor demand constant. If it grows slower than this, we expect the demand for labor to fall and the number of jobs to decrease or the average number of hours worked to fall.

Since the recovery began in the summer of 2009 GDP growth has averaged just under 2.5 percent. These means that we should not have expected the economy to create any jobs over this period. In fact, it has added almost 1,500,000. Insofar as there is a mystery, given the weak growth of the economy over the last two and a half years, it is why the economy added so many jobs.

The Wall Street Journal had a bizarre article about capital investment and robotics to explain the slow job growth in this recovery. There actually is a much simpler explanation, it’s called “slow growth.”

Productivity growth has averaged close to 2.5 percent since 1995. That means the economy must grow at a 2.5 percent rate just to keep labor demand constant. If it grows slower than this, we expect the demand for labor to fall and the number of jobs to decrease or the average number of hours worked to fall.

Since the recovery began in the summer of 2009 GDP growth has averaged just under 2.5 percent. These means that we should not have expected the economy to create any jobs over this period. In fact, it has added almost 1,500,000. Insofar as there is a mystery, given the weak growth of the economy over the last two and a half years, it is why the economy added so many jobs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT went overboard in an effort to present numbers in no context whatsoever when it discussed efforts to pay for the extension of the payroll tax cut for the rest of 2012. The article discusses the cost of various spending cut proposals without putting them in any context whatsoever, including even the number of years involved.

For example, it told readers that requiring a Social Security number to claim the child tax cut would save $9.4 billion according to the Congressional Budget Office. The article never gives a time period over which these savings would be realized.

Presumably, this is a 10-year estimate. Over this period, the federal government is projected to spend more than $43 trillion, so these savings would amount to a bit more than 0.02 percent of projected spending over this period. It would be helpful to include some context when presenting these numbers, otherwise they have little meaning to readers.

The NYT went overboard in an effort to present numbers in no context whatsoever when it discussed efforts to pay for the extension of the payroll tax cut for the rest of 2012. The article discusses the cost of various spending cut proposals without putting them in any context whatsoever, including even the number of years involved.

For example, it told readers that requiring a Social Security number to claim the child tax cut would save $9.4 billion according to the Congressional Budget Office. The article never gives a time period over which these savings would be realized.

Presumably, this is a 10-year estimate. Over this period, the federal government is projected to spend more than $43 trillion, so these savings would amount to a bit more than 0.02 percent of projected spending over this period. It would be helpful to include some context when presenting these numbers, otherwise they have little meaning to readers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Senator Patrick Leahy, the sponsor of the Protect Intellectual Property bill, claimed that if Congress rejected his bill it would “cost American jobs.” This is almost certainly not true.

Insofar as individuals are able to able to gain access to copyrighted material for which they would otherwise have to pay, they are able to save money. This if effectively the same thing as a tax cut, putting more money in their pocket, the vast majority of which will be spent on goods and services in their community, thereby creating jobs.

If they are denied access to this material, most would not be paying the copyright-protected price. Insofar as some of these people would pay the copyright protected price, it would mean some additional revenue to companies like Disney and Time-Warner. Most immediately this would mean higher profits for these companies. It may have some marginal impact on their employment, but the jobs lost from the money taken away from consumers would almost certainly be larger than the jobs gained by allowing these entertainment companies to gain more revenue. This is similar to imposing quotas on imported clothes. This will lead to more jobs in the textile industry, but fewer jobs everywhere else.

Senator Leahy’s bill will also impose additional cost on search engines like Google and intermediaries like Facebook. These costs are like a tax on the Internet. They pull money out of the economy and make these providers less efficient.

The NYT should have included this sort of economic analysis along with Senator Leahy’s comments.

Senator Patrick Leahy, the sponsor of the Protect Intellectual Property bill, claimed that if Congress rejected his bill it would “cost American jobs.” This is almost certainly not true.

Insofar as individuals are able to able to gain access to copyrighted material for which they would otherwise have to pay, they are able to save money. This if effectively the same thing as a tax cut, putting more money in their pocket, the vast majority of which will be spent on goods and services in their community, thereby creating jobs.

If they are denied access to this material, most would not be paying the copyright-protected price. Insofar as some of these people would pay the copyright protected price, it would mean some additional revenue to companies like Disney and Time-Warner. Most immediately this would mean higher profits for these companies. It may have some marginal impact on their employment, but the jobs lost from the money taken away from consumers would almost certainly be larger than the jobs gained by allowing these entertainment companies to gain more revenue. This is similar to imposing quotas on imported clothes. This will lead to more jobs in the textile industry, but fewer jobs everywhere else.

Senator Leahy’s bill will also impose additional cost on search engines like Google and intermediaries like Facebook. These costs are like a tax on the Internet. They pull money out of the economy and make these providers less efficient.

The NYT should have included this sort of economic analysis along with Senator Leahy’s comments.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Morning Edition did a segment this morning on the 35 hour work week in France. To show how bad the 35 hour work week is, the segment told listeners that hospital workers had accumulated 2 million days worth of overtime, which they will have to take as days off by the end of 2012. It warned that this would force hospitals to shut down for months at a time.

Most listeners would have little ability to assess the risk from taking this many days of leave since they probably don’t have much idea of how big France’s hospital sector is. In the United States the hospital sector employs 4.8 million workers. If the sector in France is proportional to the size of its employed workforce, then France has approximately 1.2 million workers in the hospital sector. This means that if everyone uses their days off (workers in the U.S. often lose days of paid leave), they will have to take an average of 1.7 extra days off in 2012. Is that scary or what?

The piece also included the completely unsourced assertion that few people believe that the 35 hour work week has led to increased employment by dividing up jobs. The people who do not believe that the shorter work week created jobs must believe that the 35 hour work week led to sharp increases in productivity. If workers can produce the same amount in 35 hours as they did in 39 hours (the previous standard work week in France), it would imply an 11 percent increase in productivity.

This would be an astonishing gain in productivity. Economists view productivity as the primary determinant of living standards. Productivity growth is the whole point of all those great plans for tax cuts (usually for rich people) that people like Mitt Romney, Newt Gingrich, and Paul Ryan keep throwing on the table. If NPR’s sources are correct in their view, and shorter work weeks lead to massive gains in productivity (none of the tax cut bills are projected to lead to productivity gains of even one-fifth this size), then shorter work weeks could be a great way to both increase equality and improve growth: a classic win-win situation.

[Addendum: The transcript is now available. It seems that the 2 million days referred to a single hospital in Paris, not the entire hospital system.]

[Addendum 2: Andrew Watt has a more serious discussion of the impact of the 35-hour work week in France.

Morning Edition did a segment this morning on the 35 hour work week in France. To show how bad the 35 hour work week is, the segment told listeners that hospital workers had accumulated 2 million days worth of overtime, which they will have to take as days off by the end of 2012. It warned that this would force hospitals to shut down for months at a time.

Most listeners would have little ability to assess the risk from taking this many days of leave since they probably don’t have much idea of how big France’s hospital sector is. In the United States the hospital sector employs 4.8 million workers. If the sector in France is proportional to the size of its employed workforce, then France has approximately 1.2 million workers in the hospital sector. This means that if everyone uses their days off (workers in the U.S. often lose days of paid leave), they will have to take an average of 1.7 extra days off in 2012. Is that scary or what?

The piece also included the completely unsourced assertion that few people believe that the 35 hour work week has led to increased employment by dividing up jobs. The people who do not believe that the shorter work week created jobs must believe that the 35 hour work week led to sharp increases in productivity. If workers can produce the same amount in 35 hours as they did in 39 hours (the previous standard work week in France), it would imply an 11 percent increase in productivity.

This would be an astonishing gain in productivity. Economists view productivity as the primary determinant of living standards. Productivity growth is the whole point of all those great plans for tax cuts (usually for rich people) that people like Mitt Romney, Newt Gingrich, and Paul Ryan keep throwing on the table. If NPR’s sources are correct in their view, and shorter work weeks lead to massive gains in productivity (none of the tax cut bills are projected to lead to productivity gains of even one-fifth this size), then shorter work weeks could be a great way to both increase equality and improve growth: a classic win-win situation.

[Addendum: The transcript is now available. It seems that the 2 million days referred to a single hospital in Paris, not the entire hospital system.]

[Addendum 2: Andrew Watt has a more serious discussion of the impact of the 35-hour work week in France.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Hungary is being led by a right-wing populist government that seems to have a questionable commitment to democracy. The steps it has taken to end the independence of the judiciary and undermine the fairness of future of elections are ominous. However, the NYT’s efforts to construct an economic case against the government fall badly short of the mark.

The NYT tells us that:

“Hungary serves as a cautionary tale for those who argue that Greece could regain competitiveness by reintroducing its currency. The drachma would plunge against the euro, the theory goes, and allow Greek products to compete on price with countries like Turkey.

‘Whatever you win today, it shoots you back tomorrow,’ said Radovan Jelasity, chief of the Hungarian unit of Erste Bank, an Austrian institution.

….

In theory, the plunge of the currency should help the economy by making Hungarian products less expensive abroad and cutting the cost of labor relative to neighboring countries.

But economists and business people say the advantages of a weak currency are more than canceled out by negative factors, like soaring prices for imported fuel or imported components for Hungarian factories, not to mention higher payments on foreign currency loans.

….

But the economic climate is grim, with 10.7 percent unemployment and inflation of 4.3 percent even as the economy heads into recession.”

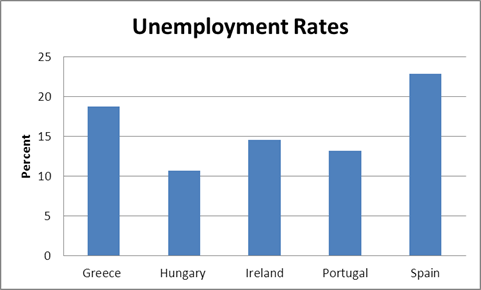

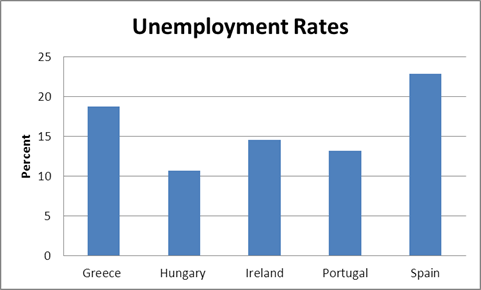

Okay, so the word is that things are really bad in Hungary with its 10.7 percent unemployment rate. Let’s see how that looks compared to the competition.

Source: OECD.

If we compare Hungary to the debt crisis countries that remain within the euro it is looking pretty good. The closest among this group is Portugal, with an unemployment rate of 13.2 percent. The others are considerably worse. (The unemployment rates given are all the most recent available, which differs somewhat across countries.)

The 4.3 percent inflation rate might be somewhat higher than is desired, but hardly a crisis. The United States had higher inflation rates many times in the last 50 years without serious economic disruptions. Furthermore, in the context of a heavily indebted population, inflation performs the valuable function of reducing the real value of debt. It is also a necessary part of the adjustment process for a country looking to regain competitiveness by reducing the value of its currency.

The moral of this story is that Hungary’s government may actually be led by bad guys, but it doesn’t seem that their policies have had terribly negative economic consequences thus far. That could change down the road, but it still appears that Hungary’s economy is doing relatively well.

Hungary is being led by a right-wing populist government that seems to have a questionable commitment to democracy. The steps it has taken to end the independence of the judiciary and undermine the fairness of future of elections are ominous. However, the NYT’s efforts to construct an economic case against the government fall badly short of the mark.

The NYT tells us that:

“Hungary serves as a cautionary tale for those who argue that Greece could regain competitiveness by reintroducing its currency. The drachma would plunge against the euro, the theory goes, and allow Greek products to compete on price with countries like Turkey.

‘Whatever you win today, it shoots you back tomorrow,’ said Radovan Jelasity, chief of the Hungarian unit of Erste Bank, an Austrian institution.

….

In theory, the plunge of the currency should help the economy by making Hungarian products less expensive abroad and cutting the cost of labor relative to neighboring countries.

But economists and business people say the advantages of a weak currency are more than canceled out by negative factors, like soaring prices for imported fuel or imported components for Hungarian factories, not to mention higher payments on foreign currency loans.

….

But the economic climate is grim, with 10.7 percent unemployment and inflation of 4.3 percent even as the economy heads into recession.”

Okay, so the word is that things are really bad in Hungary with its 10.7 percent unemployment rate. Let’s see how that looks compared to the competition.

Source: OECD.

If we compare Hungary to the debt crisis countries that remain within the euro it is looking pretty good. The closest among this group is Portugal, with an unemployment rate of 13.2 percent. The others are considerably worse. (The unemployment rates given are all the most recent available, which differs somewhat across countries.)

The 4.3 percent inflation rate might be somewhat higher than is desired, but hardly a crisis. The United States had higher inflation rates many times in the last 50 years without serious economic disruptions. Furthermore, in the context of a heavily indebted population, inflation performs the valuable function of reducing the real value of debt. It is also a necessary part of the adjustment process for a country looking to regain competitiveness by reducing the value of its currency.

The moral of this story is that Hungary’s government may actually be led by bad guys, but it doesn’t seem that their policies have had terribly negative economic consequences thus far. That could change down the road, but it still appears that Hungary’s economy is doing relatively well.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Joe Nocera’s column today argues that the financial industry may have a legitimate complaint when it says that the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill is too complicated. While the law is complicated in many areas, it is important to recognize that in many cases the industry was the source of the complication.

For example, there was a widely held view following the experience of AIG, which had issued hundreds of billions of dollars worth of credit default swaps outside of the purview of any regulator, that derivatives should be traded either on exchanges or through clearinghouses in order to increase transparency. Rules to this effect were included in Dodd-Frank.

However, the financial industry wanted to preserve the option to trade some derivatives over-the-counter. Therefore they included a series of exemptions in the legislation.

These exemptions are quite complicated. In contrast, a blanket requirement that derivatives had to be traded through a third party would be relatively simple. However it was the industry that added the complexity.

There are many other areas where a similar story could be told. That is why it is hypocritical for someone like J.P. Morgan CEO to complain about the complexity of the legislation.

Joe Nocera’s column today argues that the financial industry may have a legitimate complaint when it says that the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill is too complicated. While the law is complicated in many areas, it is important to recognize that in many cases the industry was the source of the complication.

For example, there was a widely held view following the experience of AIG, which had issued hundreds of billions of dollars worth of credit default swaps outside of the purview of any regulator, that derivatives should be traded either on exchanges or through clearinghouses in order to increase transparency. Rules to this effect were included in Dodd-Frank.

However, the financial industry wanted to preserve the option to trade some derivatives over-the-counter. Therefore they included a series of exemptions in the legislation.

These exemptions are quite complicated. In contrast, a blanket requirement that derivatives had to be traded through a third party would be relatively simple. However it was the industry that added the complexity.

There are many other areas where a similar story could be told. That is why it is hypocritical for someone like J.P. Morgan CEO to complain about the complexity of the legislation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión