Haiti: Relief and Reconstruction Watch is a blog that tracks multinational aid efforts in Haiti with an eye towards ensuring they are oriented towards the needs of the Haitian people, and that aid is not used to undermine Haitians' right to self-determination.

After the January earthquake, a number of donors and NGOs began large scale food distribution programs. Post earthquake surveys had found a large spike in food insecure households directly after the earthquake. A recent World Bank Policy Research Working Paper from Damien Échevin notes that three weeks after the earthquake “31% of the households were experiencing limited or severe food insecurity (22% and 9% respectively), that is a [sic] nearly double the food insecurity prevalence observed before the earthquake.” In a follow up survey four months later, the number of food insecure households had decreased, but only to 27 percent. Échevin concludes:

So, shortly after the earthquake, assistance programs allocation prove not to have been effective in targeting the most vulnerable people in the directly affected area. Five months after the earthquake, it appears that things had not really changed: although food assistance may have contributed to decrease the prevalence of food insecurity over the period, authorities still seemed unable to provide an efficient allocation of assistance programs…indeed, assistance also appeared to benefit less to families headed by women and less to households with disabled members, which is contradictory with an “optimal” targeting that would make those most vulnerable eligible for assistance in priority.

The World Bank report also has some interesting conclusions about Food-for-Work and Cash-for-Work plans:

When focusing of cash and food-for-work programs, we find that these programs are not specifically targeted at people who are most in need, be it because of their low level of subsistence or because of earthquake-related losses. Pre-earthquake participation to programs appears to be an important determinant of post-earthquake participation. What is more, cash-for-work is very rarely declared as the main source of household income.

The report provides some statistical backing to the first-hand accounts of the problems with food distribution in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake and with the problematic Cash-for-Work programs from USAID/OTI.

After the January earthquake, a number of donors and NGOs began large scale food distribution programs. Post earthquake surveys had found a large spike in food insecure households directly after the earthquake. A recent World Bank Policy Research Working Paper from Damien Échevin notes that three weeks after the earthquake “31% of the households were experiencing limited or severe food insecurity (22% and 9% respectively), that is a [sic] nearly double the food insecurity prevalence observed before the earthquake.” In a follow up survey four months later, the number of food insecure households had decreased, but only to 27 percent. Échevin concludes:

So, shortly after the earthquake, assistance programs allocation prove not to have been effective in targeting the most vulnerable people in the directly affected area. Five months after the earthquake, it appears that things had not really changed: although food assistance may have contributed to decrease the prevalence of food insecurity over the period, authorities still seemed unable to provide an efficient allocation of assistance programs…indeed, assistance also appeared to benefit less to families headed by women and less to households with disabled members, which is contradictory with an “optimal” targeting that would make those most vulnerable eligible for assistance in priority.

The World Bank report also has some interesting conclusions about Food-for-Work and Cash-for-Work plans:

When focusing of cash and food-for-work programs, we find that these programs are not specifically targeted at people who are most in need, be it because of their low level of subsistence or because of earthquake-related losses. Pre-earthquake participation to programs appears to be an important determinant of post-earthquake participation. What is more, cash-for-work is very rarely declared as the main source of household income.

The report provides some statistical backing to the first-hand accounts of the problems with food distribution in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake and with the problematic Cash-for-Work programs from USAID/OTI.

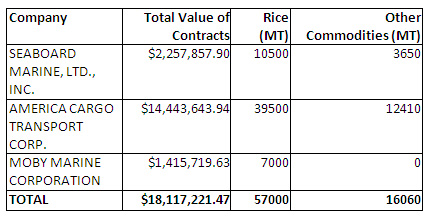

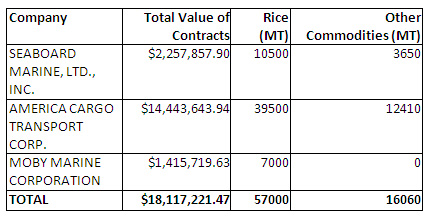

Between January 14 and February 26 2011, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) signed nine contracts with three shipping companies to send 73,000 Metric Tons of rice and other commodities in Title II emergency food aid to Haiti, public records from the Federal Procurement Database System show. The contracts in total cost taxpayers over $18 million dollars, as shown in the table below.

According to the World Food Program Food Aid Information System, Haiti received over 110,000 Metric Tons of rice as food aid in 2010, yet only five percent came in the form of local procurement. Although we have previously discussed the benefits of local procurement of food aid and efforts to increase it, the role of the shipping industry has often been neglected from these discussions. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found in a 2009 report that:

Certain legal requirements to procure U.S.-grown agricultural commodities for food aid and to transport those commodities on U.S.-flag vessels may constrain agencies’ use of LRP [local and regional procurement].

The role of the shipping industry in preventing food aid reforms in the U.S. was the subject of a 2010 paper entitled “Food Aid and Agricultural Cargo Preference” (PDF) from researchers at Cornell University. The paper explains why the barriers to reforming the delivery of food aid are so much greater in the U.S. than elsewhere:

The sheer size and history of US food aid programs obviously create inertia that differentiates it from most donors. But in political economy terms, arguably the most distinctive feature of US food aid programs is the intimate involvement of ocean carriers, who benefit from little?known agricultural cargo preference (ACP) requirements absent in other donor countries. While food aid policy reforms have had to overcome resistance from agribusiness and some nongovernmental organization (NGO) interests in every donor nation, the “iron triangle” of interests formed by agribusiness, some NGOs and ocean carriers has been a uniquely effective lobby for the status quo in US food aid policy.

In addition to the problems associated with the actual delivery of food aid, the report finds that the cost of the agricultural cargo preference to U.S. taxpayers is significant:

We find that meeting ACP requirements for USDA and USAID programs cost US taxpayers roughly $140 million per year in FY2006 and that roughly half of those costs were borne by food aid agencies rather than by the Maritime Administration. ACP costs USAID a significant portion of its food aid programming resources under Title II of Public Law 480, nearly equivalent to the value of USAID’s entire Title II non?emergency food aid to Africa.

Between January 14 and February 26 2011, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) signed nine contracts with three shipping companies to send 73,000 Metric Tons of rice and other commodities in Title II emergency food aid to Haiti, public records from the Federal Procurement Database System show. The contracts in total cost taxpayers over $18 million dollars, as shown in the table below.

According to the World Food Program Food Aid Information System, Haiti received over 110,000 Metric Tons of rice as food aid in 2010, yet only five percent came in the form of local procurement. Although we have previously discussed the benefits of local procurement of food aid and efforts to increase it, the role of the shipping industry has often been neglected from these discussions. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found in a 2009 report that:

Certain legal requirements to procure U.S.-grown agricultural commodities for food aid and to transport those commodities on U.S.-flag vessels may constrain agencies’ use of LRP [local and regional procurement].

The role of the shipping industry in preventing food aid reforms in the U.S. was the subject of a 2010 paper entitled “Food Aid and Agricultural Cargo Preference” (PDF) from researchers at Cornell University. The paper explains why the barriers to reforming the delivery of food aid are so much greater in the U.S. than elsewhere:

The sheer size and history of US food aid programs obviously create inertia that differentiates it from most donors. But in political economy terms, arguably the most distinctive feature of US food aid programs is the intimate involvement of ocean carriers, who benefit from little?known agricultural cargo preference (ACP) requirements absent in other donor countries. While food aid policy reforms have had to overcome resistance from agribusiness and some nongovernmental organization (NGO) interests in every donor nation, the “iron triangle” of interests formed by agribusiness, some NGOs and ocean carriers has been a uniquely effective lobby for the status quo in US food aid policy.

In addition to the problems associated with the actual delivery of food aid, the report finds that the cost of the agricultural cargo preference to U.S. taxpayers is significant:

We find that meeting ACP requirements for USDA and USAID programs cost US taxpayers roughly $140 million per year in FY2006 and that roughly half of those costs were borne by food aid agencies rather than by the Maritime Administration. ACP costs USAID a significant portion of its food aid programming resources under Title II of Public Law 480, nearly equivalent to the value of USAID’s entire Title II non?emergency food aid to Africa.