April 18, 2012

Paul Krugman has kicked off a debate in the blogosphere about the historic decline in inequality in Latin America over the last decade and the role of left-of-center governments. This is a topic I have looked at in quite some detail and so naturally welcome any debate. Citing a paper by Giovanni Andrea Cornia, Krugman tells us that:

“The region moved left politically circa 2000, partially turning its back on the Washington Consensus — and there has been a dramatic reversal in inequality trends.”

It is clear that on average inequality has fallen in Latin America. Krugman links to a graph from Cornia that shows average regional inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, decreasing during the last decade.

Well, as it turns out, Juan Carlos Hidalgo from the Cato Institute is none too pleased with Krugman’s analysis, claiming he has a “tortuous relationship with the facts.”

Hidalgo starts off by asking if we can “assign the recent decline in inequality in Latin America to any specific ideology?” and cites a recent paper that argues “there was no strict correspondence between declining inequality and either the ideological profile of national governments or any specific redistributive initiatives.”

Yes, inequality has decreased in most Latin American countries, not just countries with left-of-center governments. But what matters isn’t if centrist or rightwing governments haven’t reduced inequality while left-of-center governments have. The relevant question is: have left-of-center countries reduced inequality more than the rest?

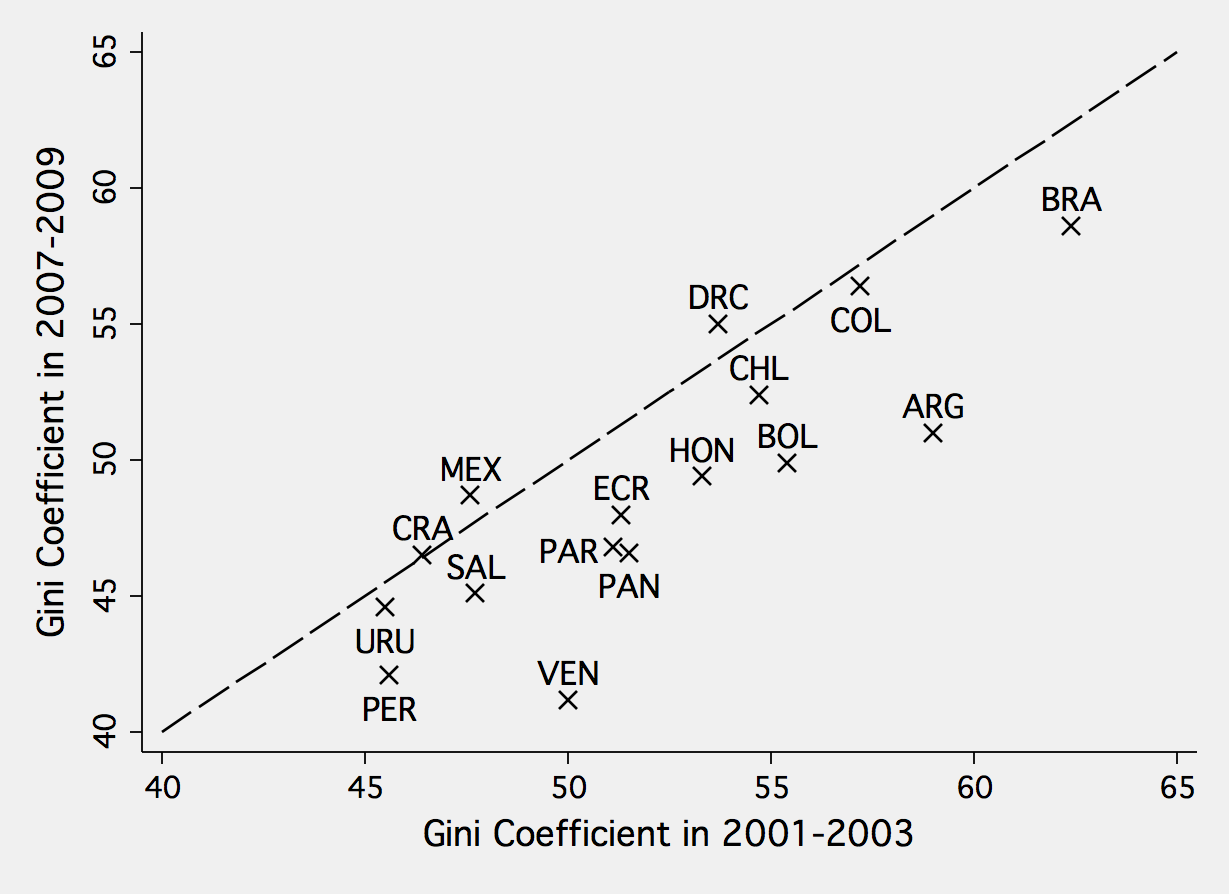

Below I reproduce a graph from my own paper that allows us to get a better idea of the country variation behind the average reduction in inequality during the 2000s:

The graph compares the Gini coefficient in each country between the beginning of the decade (2001-03) and the end (2007-09). Countries below the 45-degree line reduced inequality throughout the decade and the farther below the line, the larger the decrease. As can be seen in the graph, the story is quite clear: there has been an overwhelming decrease in inequality and based on a casual observation, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Venezuela (four left-of-center countries) appear to have performed particularly well.

Now, of course, this on its own doesn’t tell us much because it doesn’t take into account the effect of external factors and other economic conditions in reducing inequality. To find out if left-of-center governments did in fact reduce inequality more than their counterparts in any statistically meaningful way we need regression analysis – something that the paper Hidalgo cites does not attempt, and which, incidentally the paper Krugman cites does.

In fact, in recent years several papers, including my own, have used econometric techniques to formally look at this question. Although the statistical methods have differed and disagreements exist over how to ideologically categorize different countries, the main take away is that there is statistical evidence that countries with left-of-center governments have on average decreased inequality more than their counterparts. As my own work has shown, the econometric evidence does become murkier when one starts to distinguish between different types of left-of-center governments, but this does not negate the broader findings that there is a relationship between moving away from the Washington Consensus and reducing inequality.

To be fair to Hidalgo, he questions if its really true that most of the region has shifted away from Washington Consensus policies and notes that what matters isn’t the “ideological affiliation” of a country, but rather its economic policies. Hidalgo points to the case of Chile, which according to him has largely kept the Washington Consensus policy framework intact.

What’s puzzling however is that while Hidalgo chastises Krugman and Cornia for relying too heavily on “ideological labels,” the only alternative metric he offers is a nebulous “Economic Freedom Index,” which apparently increased during the period in question. And while Hidalgo pontificates about the importance of examining actual economic policies, Cornia’s paper actually provides a well reasoned and quite nuanced discussion of the policy changes that have taken place (for instance a move towards managed exchange rate regimes and counter-cyclical or neutral fiscal policies).

Where Chile is concerned, it is worth mentioning that although many of its macroeconomic policies have remained the same, much of its economic success over the last two decades can be linked to policies well outside of the Washington Consensus framework. Chile is actually the paradigmatic example of a country that successfully used capital controls to insulate its economy from volatile international finance (John Williamson, who originally coined the Washington Consensus term, didn’t recommend unrestricted capital mobility but this has nevertheless been part of the package). And throughout the 1990s, Chile had several restrictions on foreign direct investment designed to discourage speculative investors and promote the development of its exports sector.

Not to belabor the point, but do national ownership over natural resources, legally mandated counter-cyclical fiscal policy and state-supported promotion of the export sector sound like a country following the Washington Consensus playbook? (Just to be clear, I’m still talking about Chile.)