June 11, 2024

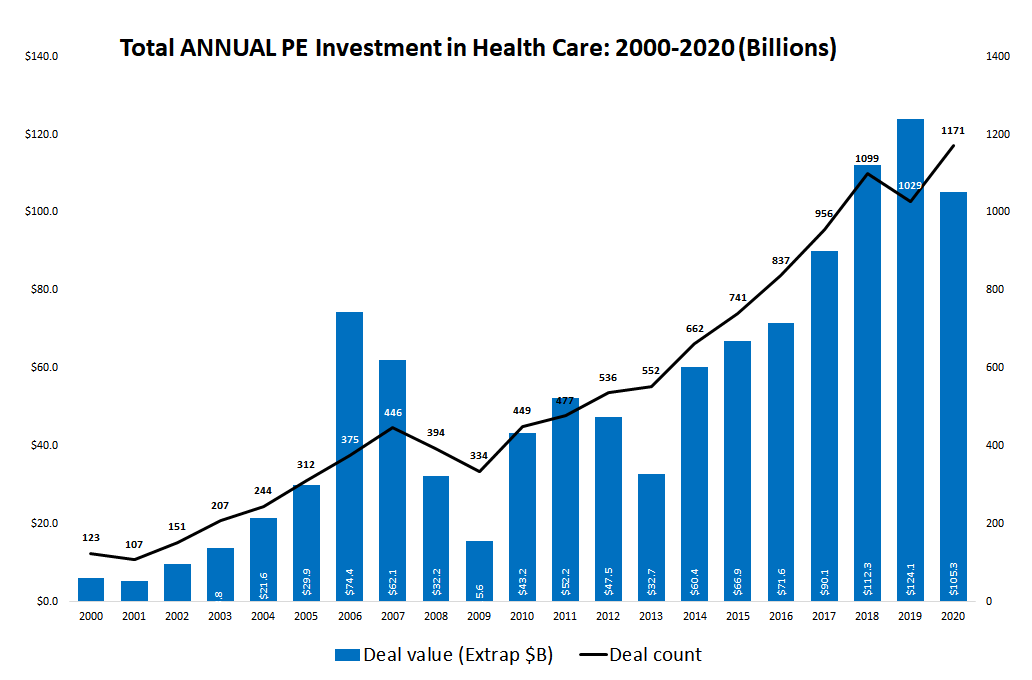

Private equity’s entrance into health care since 2000 has been dramatic. Both the number of private equity (PE) deals and annual PE investments in health care increased tenfold between 2001 and 2020, and peaked in 2021.

Until now, lax corporate transparency and accountability regulations meant that there was nothing anyone could do when corporate owners of health care companies enriched themselves and their investors while driving the companies they owned to financial disaster. They got away with their ill-gotten gains while the hospitals’ stakeholders and communities paid the price. But that is about to change.

Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) announced the Corporate Crimes Against Health Care Bill. This new legislation will empower state Attorneys General and the US Attorney General to claw back funds and impose civil and, in the case where a patient dies, criminal penalties on a PE firm and related financial actors whose financial engineering activities drove the health care organization to financial ruin.

Senator Warren’s Corporate Crimes Against Health Care bill will curb the use of financial engineering strategies that endanger the integrity of the US health system. It will curb abuses that I and other researchers investigating the financialization of America’s health system have identified. It will protect the right of patients to the best care possible, of professionals and frontline workers to adequate staffing and time with patients, and of communities to accessible health care.

In the case where looting the hospital results in a patient’s death, the Corporate Crimes Against Health Care bill mandates that executives of the PE firm and the failing health care company will be subject to a new criminal penalty of up to six years in prison.

Regulators — state attorneys general and the US attorney general — will be able to claw back all compensation paid to PE firms and health company executives who unjustly enriched themselves as the health care organization spiraled toward serious, avoidable financial difficulties. A corporate owner who shows that it could not have prevented the financial troubles will not be penalized.

Importantly, and proactively, the legislation would prohibit federal health programs from making payments to hospitals and other health organizations that sell assets to a real estate investment trust (REIT).

It provides transparency by requiring health care entities receiving federal funding to report changes in ownership and control as well as financial data including debt. Health care professionals caught between the demands of their corporate owners and the needs of their patients experience this conflict in deeply personal and disabling ways that have been termed “moral injury.”

The new legislation will mandate a Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General report to Congress on the harms of corporatization in health care.

Today, private equity has ownership stakes in nearly every segment of health care from doctors’ practices and hospice agencies to hospitals, health IT, and medical debt collection. The supercharged drive for profits by PE owners clashes with the public’s right to an equitable and inclusive health system that puts patients’ needs first. PE firms prey on the most vulnerable members of society: children with behavioral problems, the frail and poor elderly, the dying being cared for by hospice agencies, and acutely ill patients in hospitals.

Private equity has a well-worn playbook that it uses to legally loot health care companies. These strategies erode the financial stability of organizations across the health care spectrum. But the effects of PE’s relentless pursuit of maximal profit in the four to seven-year window before it resells the company may be most pernicious in hospitals. The scale of hospitals and affiliated health systems in terms of the number of patients cared for, professional and frontline workers employed, and the communities they serve, dwarfs other health segments. A hospital closure can devastate the community it serves.

Private Equity uses standard operating procedures, like these, to extract wealth from the companies it owns:

- Recruit investors who commit capital to a private equity fund. For instance, investors like pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds, and high net worth individuals provide the funds, but they don’t make any decisions.

- Buy health care companies and providers for the PE fund’s portfolio of assets, transforming an organization whose mission is to serve the public good into a financial asset to be bought and sold.

- Use the capital the investors have contributed to the PE fund to make the “down payment” on the acquisition of the health organization. The PE firm contributes 2 cents to the PE fund for every dollar the investors put in, so it has very little of its own money at risk.

- Use lots of debt (leverage) to acquire the health organization and then obligate the acquired enterprise to repay the borrowed funds. Even though the debt was used by the PE fund to buy the company, which it now owns, it is the company, and not the fund, that is on the hook to repay the debt. This is a so-called leveraged buyout.

- The higher the use of debt, the greater the profit for the PE firm and its investors when the company is sold a few years later. But debt is a two-edged sword. It weakens the health organization, greatly increasing the risk it will face financial distress and bankruptcy.

- Require the health company to take on more debt and use the proceeds to pay dividends to the organization’s owners, i.e., the PE firm and its investors.

- Strip the health organization of its assets by selling off its real estate to a real estate investment trust (REIT) in a sale-leaseback agreement. The proceeds of the sale are used to line the pockets of the PE firms and their investors. The health care organization is left with the lease and must now pay rent on property it formerly owned.

- Require the health organization, which the PE fund now owns, to agree to pay you for vaguely specified “monitoring” services, colloquially referred to as “money for nothing.”

- Engage in cost cutting and tax manipulation to increase cash flow, known as “putting lipstick on the pig.”

- Sell the dolled-up, debt-ridden company at a profit in four to seven years after acquiring it. Give the PE firm 20 percent of the profit even though it only put up 2 percent of the equity.

- Walk away scot-free if the health company sinks under the weight of its fees, debts, and rent payments. Keep all the money you skimmed off the top to line the pockets of your executives. Leave the patients, workers, creditors, and community to pay the price.

In hospitals and nursing homes, the financial strategies employed by private equity siphon off taxpayer dollars that fund Medicare and Medicaid and are meant to pay for health care for patients. The public’s money is used to unjustly enrich PE firms and their investors. Mortality is higher in PE-owned nursing homes. Hospital patients are left with poor care and a higher incidence of “adverse events” in hospitals — ulcerated bed sores, falls, nasty hospital-acquired illnesses — that complicate their recovery.

We have seen this most recently in the dramatic implosion of the Steward Health System, now bankrupt and stranding patients, workers, vendors, and creditors. Many communities are left without a way to meet the health needs of their residents when private equity deals close a safety net hospital or the only hospital in an area.

PE firm Cerberus Capital bought out a small troubled Catholic hospital system in the Boston area, Caritas Christi Health Care, in 2010. After a few years, Cerberus sold off most of its hospitals’ property to MPT, a real estate investment trust. This left the hospitals saddled with long-term inflated leases.

Cerberus used the sale proceeds to pay itself hundreds of millions in dividends and then used the Steward system as a platform for a massive debt-driven acquisition strategy to buy out 27 hospitals in nine states in three years between 2016 and 2019, then roll them up into a dominant health care company in its local markets.

Steward’s debt load exploded, and by 2019, its financials were deeply in the red. Its Massachusetts hospitals were the worst financial performers of any system in the state and had higher than average rates of patient falls, hospital-acquired infections, and patient readmissions. Unable to find a buyer for its financially weakened hospitals, Cerberus exited Steward in 2020 by lending a group of the hospital system’s physicians the money to buy the troubled chain, leaving them to cope with above-market rent payments and massive debt. Cerberus pocketed $782 million for itself and its investors from its ownership of Steward.

Steward declared bankruptcy this year and will shutter most of its hospitals. Its nine Massachusetts hospitals, four of them safety net hospitals, served 200,000 patients a year. Closing them will leave patients without access to emergency and other vital medical services, and with long travel times for surgeries, cancer care, and care for chronic conditions.

The most tragic story to emerge from Steward’s financial fiasco is the death of a new mother just a day after giving birth at a Steward hospital. The woman had a deep bleed that could have been treated with an embolism coil. But the hospital did not have one. Weeks earlier the devices had been repossessed by their manufacturer because the hospital failed to pay for them.

Steward is not an isolated case. In 2010, PE firm Leonard Green acquired five community health systems, renamed them Prospect Medical Holdings, and expanded the system through debt-financed mergers and acquisitions to 20 hospitals and 165 clinics by 2019. The hospital system’s debt level multiplied and its quality ratings fell to among the lowest in the country. It sold off much of its hospitals’ real estate to MPT so that its hospitals now pay inflated rents.

In the Fall of 2019, Leonard Green shut down its hospital in San Antonio, Texas as well as the hospital’s home health division, its specialty health and behavioral center, and other facilities, laying off nearly a thousand workers. By that time, it had extracted at least $658 million in fees and dividend recapitalizations. Taxpayers pay: 55 percent of Prospect’s annual net revenue through Medicare and Medicaid.

In the Fall of 2023, Leonard Green closed Delaware Memorial Hospital, a debt-ridden safety net hospital in a middle-class suburb of Philadelphia, and was given a nine-month grace period to find a buyer for Crozer Health, a failing four-hospital chain in Pennsylvania’s Chester County.

Apollo Global Management is currently the largest private equity owner of hospitals. It owns LifePoint Health and Scion Health, which, between them, have a total of 244 hospitals. This is more than half of the 457 acute care, behavioral, and specialty hospitals the Private Equity Stakeholder Project has identified as private equity owned.

LifePoint is the largest chain of mostly rural hospitals in the US. It owns 62 acute care hospitals serving communities in 16 states. In early 2020, Lifepoint sold the real estate of 10 of its hospitals in six states to Medical Properties Trust in a sale-leaseback deal that enriches Apollo and leaves the hospitals with long-term leases and escalating rent payments.

On March 17, Senator Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) sent a letter to LifePoint inquiring about this and other “opaque and questionable acquisitions, mergers, and other related party transactions…” Concerned about the financial condition of the LifePoint hospitals and dissatisfied with the responses he got from its PE owner, he is investigating further. Along with other health care companies owned by PE firms, LifePoint is the subject of two US Senate inquiries — one of them co-led by Senator Grassley.

In the last fifteen years, the private equity industry’s growth has rested on a foundation of sand, supported by secrecy, misinformation, hype, and poor institutional governance. The private equity industry, controlling trillions of dollars in assets, sorely needs adult supervision, independent verification, and public information dissemination.

Not only does the Corporate Crimes Against Health Care bill curb the use of financial engineering strategies that endanger the integrity of the US health system; it offers justice for those harmed.