Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

August 5, 2011 (Jobs Byte)

By Dean Baker

The employment rate for blacks hit its 4th consecutive low for the downturn.

The Labor Department reported that the economy created 117,000 jobs in July and revised prior months’ growth up slightly to bring the average over the last three months to 72,000. This rate of job growth is below the 90,000 a month needed to keep pace with the growth of the labor force. Consistent with this fact, the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) fell slightly to 58.1 percent, tying its previous low for the downturn. While the unemployment rate edged down to 9.1 percent, this was entirely attributable to people leaving the labor force.

There were some unusual patterns in job creation in July. The goods-producing sector accounted for 40,000 new jobs, with mining, construction and manufacturing all adding jobs in the month. Mining-support activity added 8,000 jobs for the second straight month, bringing growth over the last year to 65,500 — an increase of almost 22 percent.

Construction added 8,000 jobs after losing 5,000 jobs in June. Employment is up 30,000 over the last year. Month-to-month levels are likely to jump around as employment in the sector stays roughly even. Manufacturing added 24,000 jobs, but half of this was in the automobile industry. That is likely an artifact of seasonal adjustments as fewer plants shut for retooling in July than in the past.

Retail added 25,900 jobs, roughly twice the average over the last year. Health care added 31,300 jobs, a bit more than the 25,000 average over the last year. Like retail, this was probably a bounce back from weak growth the prior two months.

Restaurants added just 300 jobs after losing 2,500 over the prior two months. This sector had been adding jobs at a rate of close to 20,000 a month.

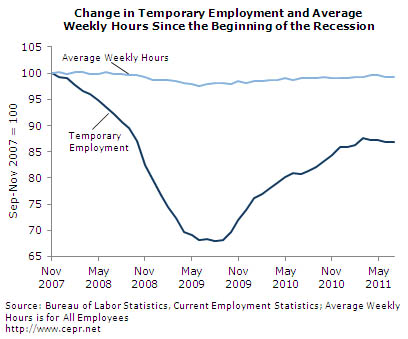

The temp sector added just 300 jobs in July. Employment in the temp sector is down 17,700 jobs since March. This is noteworthy because it directly contradicts the business uncertainty story. If businesses are holding back on hiring because they are worried about regulations, taxes, or debt default then they would be hiring temps in large numbers; however, temp employment is still down by almost 16 percent from its pre-recession level.

In the same vein, employers should be increasing the length of the average workweek as they work their existing work force more hours in order to avoid hiring new workers. (This would also be the case if there were a problem of structural unemployment due to a skills/job mismatch.) In fact, the length of the average workweek has been essentially flat over the last year and is still below the pre-recession level.

The government sector shed 37,000 jobs in July, with 35,000 of these at the state and local level. With governments at all levels cutting back, we are likely to see job loss of close to 30,000 a month for the next year.

A 0.5 percentage-point drop in the EPOP for black men was the main factor driving down the overall employment rate as the EPOP for white women was unchanged and the EPOP for black women edged up by 0.1 percentage-points. The EPOP for black teens fell 1.6 percentage-points to 13.9 percent, near the low point for the downturn. EPOPs for blacks overall fell by 0.3 percentage-points, hitting a fourth-consecutive low for the slump.

Other data in the household survey support the overall weak picture of the labor market. The percentage of unemployment attributable to people voluntarily quitting their jobs fell to 6.7 percent, near a low for the downturn. The average duration of unemployment rose to 40.4 weeks, another high for the downturn. The number of discouraged workers reported for July is down only slightly from the 2010 level.

Overall this report presents a bleak picture of the labor market. Over the last three months, job growth has been below the level needed to keep pace with the growth of the labor force. There is no sector showing especially strong growth right now, and with the government shedding 30,000 jobs a month, we will be fortunate if the unemployment rate doesn’t rise over the rest of the year.