Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Donald Trump Is Confused: Tariffs and Taxes

Understand the complexities as Trump appears confused about tariffs and the implications for U.S. manufacturing and tax policy.

Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Understand the complexities as Trump appears confused about tariffs and the implications for U.S. manufacturing and tax policy.

Article

Ecuador and Canada recently finalized negotiations for a free trade agreement, which is set to boost mining. However, the deal raises concerns over a conflict of interest, as Ecuadorian President Noboa’s family holds a stake in a Canadian mining company. The agreement also grants Canadian companies the ability to sue Ecuador in international tribunals.

Article • Expose the Heist: Power and Policy in Unprecedented Times

Another round of mass firings at Department of Health and Human Services hurts workers and imperils public health.

Article • Expose the Heist: Power and Policy in Unprecedented Times

The leadership in the Trump White House isn’t about rewarding merit – it’s about loyalty to the MAGA agenda.

Article • Expose the Heist: Power and Policy in Unprecedented Times

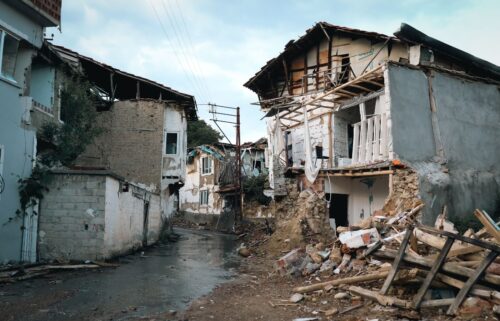

The Trump administration is planning to radically cut FEMA. Will they leave communities to fend for themselves after major disasters?

Article • Sanctions Watch

The US ramps up efforts targeting Cuban medical missions, while it appears that maximum pressure sanction are returning to Venezuela and Iran. A New CEPR issue brief explores how economic sanctions drive migration.

Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Trump’s tariffs may lead to closer ties between Canada and China.

Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Patent and copyright monopolies redistribute an enormous amount of income upward. We should be talking about them when we talk about an abundance agenda.

Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

I almost always enjoy Harry Enten’s analyses on CNN. He is usually thoughtful and on target. But he took a big swing and a miss in a piece on the “fed up” consumer.

Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Remembering Robert McChesney, a significant voice on media’s role in democracy and progressive thought. He will be missed.