Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Dr. Trump’s Crazy Tariff Formula

Trump’s crazy tariff formula will amount to the largest tax increase in the country’s history.

Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Trump’s crazy tariff formula will amount to the largest tax increase in the country’s history.

Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Friedman is right that China has surpassed the US in many areas of technological power. But he’s wrong when he claims that China needs the United States to buy its stuff.

Article • Data Bytes

The Trump administration’s economic and political upheavals have yet to show up in a big way in the labor market data. March may be a turning point.

Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Trump appears to be confused about what tariffs will do for US manufacturing jobs and overall tax policy.

Article

Ecuador and Canada recently finalized negotiations for a free trade agreement, which is set to boost mining. However, the deal raises concerns over a conflict of interest, as Ecuadorian President Noboa’s family holds a stake in a Canadian mining company. The agreement also grants Canadian companies the ability to sue Ecuador in international tribunals.

Article • Expose the Heist: Power and Policy in Unprecedented Times

Another round of mass firings at Department of Health and Human Services hurts workers and imperils public health.

Article • Expose the Heist: Power and Policy in Unprecedented Times

The leadership in the Trump White House isn’t about rewarding merit – it’s about loyalty to the MAGA agenda.

Article • Expose the Heist: Power and Policy in Unprecedented Times

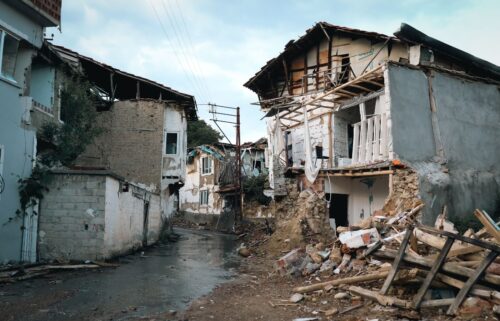

The Trump administration is planning to radically cut FEMA. Will they leave communities to fend for themselves after major disasters?

Article • Sanctions Watch

The US ramps up efforts targeting Cuban medical missions, while it appears that maximum pressure sanction are returning to Venezuela and Iran. A New CEPR issue brief explores how economic sanctions drive migration.

Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Trump’s tariffs may lead to closer ties between Canada and China.