Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

June 21, 2018, Dean Baker

Comments of Dean Baker, Senior Economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, at the Work and Family Researchers Network Conference Washington, DC

June 21, 2018

The United States is very much an outlier among wealthy countries in the relatively weak rights that are guaranteed to workers on the job. This is true in a variety of areas. For example, the United States is the only wealthy country in which private sector workers can be dismissed at will, but it shows up most clearly in hours of work.

In other wealthy countries, there has been a consistent downward trend in average annual hours of work over the last four decades. By contrast, in the United States, there has been relatively little change. While people on other wealthy countries can count on paid sick days, paid family leave, and four to six weeks of paid vacation every year, these benefits are only available to better-paid workers in the United States. Even for these workers, the benefits are often less than the average in Western European countries.

This discussion will briefly compare patterns in hours worked in wealthy countries in recent decades. It then points out the benefits of work sharing as a counter-cyclical policy. It assesses the obstacles to the broader use of work sharing and then concludes with some policy proposals that could expand its use.

Part of the benefit of work sharing is that it can allow workers and employers to gain experience with a more flexible work week or work year. It is possible that this experience can lead workers to place a higher value on leisure or non-work activities and therefore increase their support for policies that allow for reduced work hours.

Work Hours in 1970: The United States Was Not Always an Outlier

When the experience of European countries is raised in the context of proposals for expanding paid time off in the United States, it is common for opponents to dismiss this evidence by pointing to differences in national character. Europeans may value time off with their families or taking vacations, but we are told that Americans place a higher value on work and income.

While debates on national character probably do not provide a useful basis for policy, it is worth noting that the United States was not always an outlier in annual hours worked. If we go back to the 1970s, the United States was near the OECD average in annual hours worked. By contrast, it ranks near the top in 2016.

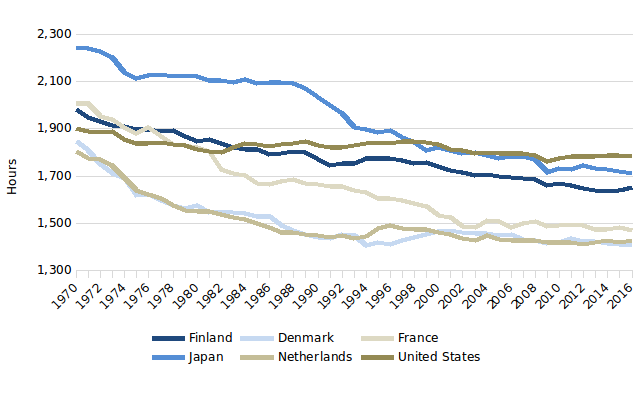

Figure 1 compares the trend in average annual hours worked between 1970 and 2016 in Denmark, Finland, France, Netherlands, Japan, and the United States. In 1970, average annual hours in the United States were slightly below the levels in France and the Netherlands, and well below the level in Japan. Hours in the United States were already substantially above the average for Denmark and Finland.[1]

Over the next five decades, the picture changes dramatically. In 1970, workers in the United States had put in on average 3 to 5 percent more hours than workers in Denmark and Finland, according to the OECD data, by 2016, this difference had grown to more than 25 percent. Workers in France and the Netherlands now have considerably shorter average work years than workers in the United States. Even workers in Japan now work about 5 percent less on average than workers in the United States.

FIGURE 1. Average Annual Hours of Work

Source and notes: OECD, see Footnote 1.

The reduction in average hours worked in these countries was the result of deliberate policy. These countries all radically increased the amount of paid time off guaranteed to workers. They either put in place or increased the number of paid vacation days mandated on employers. They also required paid sick days or paid family leave be made available to workers. France reduced its standard workweek to 35 hours with employers required to pay an overtime premium for longer hours.

The fact that the reduction in work hours over this period was policy driven suggests that it was not just national character to led shorter work hours in these countries, with workers and employers agreeing that workers should have more time off. Governments required employers to provide more time off. These policies were put in place as the result of action by democratically elected politicians, which implies there was public support for working fewer hours, but this would be the case with legislation in the United States as well. The point is that it was not simply the natural dynamic of the market that led to workers in other countries working many fewer hours, it was the result of deliberate government policy.

In the United States, our institutional structures have actually pushed in the opposite direction over most of this period. Traditional defined benefit pensions impose a substantial overhead cost, with employers making a long-term commitment to each worker that qualifies for a pension. The size of the benefit may be reduced if a worker puts in fewer hours on average, but the reduction in costs to the employer is almost certainly not proportionate to the reduction in hours.

This was even more clearly the case with health care insurance, where employers traditionally covered the cost of a health insurance policy for a worker and often their family. In fact, in prior decades it was common for health care benefits to be provided in retirement as well. This was a very large overhead cost, which would typically mean a company would be better off paying substantial overtime premiums, rather than incurring health care obligations for additional workers.

These barriers to shortening work hours have been reduced substantially in recent years. Defined benefit pensions are rapidly disappearing in the private sector. While there are some overhead costs associated even with defined contribution plans, these are small in comparison. Health care benefits have also become less common and more importantly, employers typically share the cost with their workers. In this context, it is now a common practice for health care coverage to be pro-rated, so that workers who work less than some designated minimum number of hours are required to pay a larger share of their premium.

Even if the institutional obstacles to shortening work hours may be less important in 2018 than in prior decades, we cannot escape their legacy. It was standard in other countries for increased mandates of vacation time, paid holidays, paid family leave and paid sick days to be major issues in political campaigns, as well as topics for union negotiations. The United States has a huge amount of ground to make up in this area.

It is also important to consider efforts to reduce hours as being a necessary aspect of making the workplace friendlier to women. It continues to be the case that women have a grossly disproportionate share of the responsibility for caring for children and other family members. Given this reality, a job that requires many hours of work, with few opportunities for time off, will be a much greater burden on women than men. If the standard work year were 1400 hours, as it is now in Germany, Denmark, and several other countries, rather than the 1800 hours in the United States, women would have a much easier time fitting in their caring responsibilities with a full-time job.

In this respect, it is worth noting that the United States went from ranking near the top in women’s labor force participation in 1980 to being below the OECD average in 2018. While other countries have made workplaces more family friendly, this has been much less true of the United States.

Shortening Work Hours and Full Employment

There has been a largely otherworldly public debate in recent years on the prospects that robots and artificial intelligence would lead to mass unemployment. This debate is otherworldly since it describes a world of rapidly rising productivity growth. In fact, productivity growth has been quite slow ever since 2005. The average annual rate of productivity growth over the last twelve years has been just over 1.0 percent. This compares to a rate of growth of close to 3.0 percent in the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973 and again from 1995 to 2005.

So this means that we are having this major national debate about the mass displacement of workers due to technology at a time when the data clearly tell us that displacement is moving along very slowly.[2] It is also worth noting that all the official projections from agencies like the Congressional Budget Office and the Office of Management and Budget show the slowdown in productivity growth persisting for the indefinite future. This projection of continued slow productivity growth provides the basis for debates on issues like budget deficits and the finances of Social Security.

However, if we did actually begin to see an uptick in the rate of productivity growth, and robots did begin to displace large numbers of workers, then an obvious solution would be to adopt policies aimed at shortening the average duration of the work year. The basic arithmetic is straightforward: if we reduce average work hours by 20 percent, then we will need 25 percent more workers to get the same amount of labor. While in practice the relationship will never be as simple as the straight arithmetic, if we do get a reduction in average work time, then we will need more workers.

As noted above, reductions in work hours was an important way in which workers in Western Europe have taken the gains from productivity growth over the last four decades. This had also been true in previous decades in the United States, as the standard workweek was shortened to forty hours with the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1937. In many industries, it had been over sixty hours at the turn of the twentieth century.

If the United States can resume a path of shortening work hours and get its standard work year back in line with other wealthy countries, it should be able to absorb even very rapid gains in productivity growth without any concerns about mass unemployment. While job-killing robots may exist primarily in the heads of the people who write about the economy, if they do show up in the world, a policy of aggressive reductions in work hours should ensure they don’t lead to widespread unemployment.

The Cyclical Benefits of Work Sharing

When demand for labor falls during a downturn, employers respond with a mix of reducing average hours per worker and reducing the number of workers. Work sharing is about encouraging the former response rather than the latter. In the 1930s, between 50 and 90 percent of the reduced demand for labor was met with reductions in hours rather than reduced employment. This was at least partly the result of policies put in place by the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations to encourage reduced hours as an alternative to layoffs.[3]

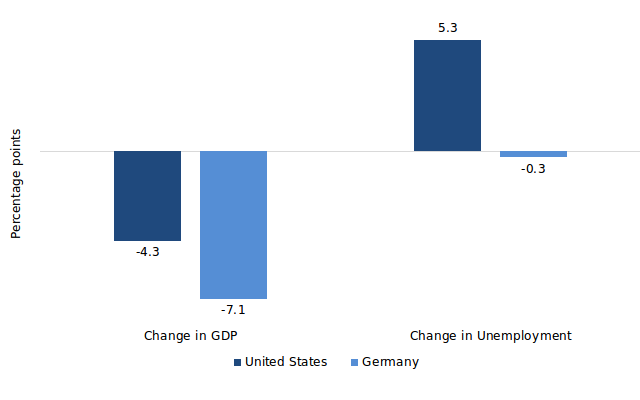

In the years following World War II, employers were much more likely to meet reduced demand for labor with layoffs than reduced hours, but this is largely a result of policy, not anything intrinsic to the nature of the modern workplace. Germany provides the clearest counter-example to the argument that large-scale unemployment is an inevitable result of a downturn in demand. In the Great Recession, Germany saw a considerably sharper decline in output than the United States, yet its unemployment rate actually fell slightly from its level just before the recession to the trough of the recession.

Figure 2 shows the changes in unemployment and GDP in Germany and the United States in the Great Recession. GDP fell by more than 7.0 percent from its peak in 2008 to its trough in 2009 in Germany, compared to a drop of just over 4.0 percent in the United States. Germany’s unemployment inched down over this period from 7.7 percent to 7.5 percent. By contrast, the unemployment rate in the United States rose from a low of 4.7 percent in the months just before the recession to a peak of 10.0 percent at the trough of the downturn.[4]

FIGURE 2. Great Recession: Changes in GDP and Unemployment

Source and notes: OECD, see Footnote 4.

The success of Germany’s government in shielding its workers from unemployment was to a substantial extent due to its Kurzarbeit policy. The standard formula provided for a reduction in hours, with 40 percent of the lost pay made up by the government and 40 percent by the employer. This could mean, for example, that a worker has a 40 percent reduction in hours, with the government making up 40 percent of the lost pay (16 percent of their prior total), the employer making up 40 percent of the lost pay (16 percent of the total) and the worker ending up with 8 percent less pay than what they had received when working full time.

Many employers opted to take advantage of this program as an alternative to layoffs with the idea that it was better to keep skilled workers attached to their job, rather than take the risk that the same workers would not be available when demand picked up again. They would then be forced to look for new workers and train them for the specific skills needed on the job.

The Kurzarbeit policy was not the only factor leading to the different employment response between Germany and the United States. Many German companies also have a system of banking hours in which workers can work extra hours during peak periods of demand and then have this time repaid with a premium during a downturn or when they choose to take the time. This hours banking was also a major way in which German employers dealt with the reduced demand for labor without laying off workers. In addition to these policy differences, Germany also has a much higher unionization rate than the United States.[5] Many unions negotiated contracts in which hours were reduced as an alternative to layoffs. The use of time banking and the greater importance of union contracts were also important factors in the differing employment responses in Germany and the United States.

Time banking and greater unionization rates are institutional features of Germany’s labor market that cannot be easily transplanted to the United States. Time banking is problematic in the US context since workers have few rights on the job. In principle, the forty-hour work week, with mandatory overtime premiums is a hard and fast rule. If a worker works more than forty hours in a week, the employer owes them premium pay.

While time banking may ostensibly be presented as an optional alternative to an overtime premium, the employee has little ability to protect themselves if an employer demands overtime be compensated by banked hours rather than premium pay. It may not be legal to fire a worker for refusing this arrangement, but they can be fired for almost any other reason. For this reason, in the context of the US labor market, optional alternatives to an overtime premium are not really optional for an employee.

The differences in unionization rates between Germany and the United States are also the result of institutional and legal differences, as well as different histories. As a practical matter, it is not plausible that the United States will see Germany’s level of unionization in the foreseeable future.

While these two avenues for encouraging reductions in hours as an alternative to layoffs may be largely foreclosed in the United States, it does have the policy option of promoting work sharing. In this respect, it is worth noting that the current practice with unemployment insurance largely goes in the other direction. In effect, unemployment insurance is paying for workers to be laid off, with workers getting half pay if they lose their jobs. If employers choose to cut back hours instead, workers get no compensation from the government for their reduction in pay. As a result, the standard use of unemployment insurance actually encourages employers to respond with layoffs instead of reducing work hours, exactly the opposite of what we should want from public policy.

Policy Options with Work Sharing and Promoting Shorter Hours

While most states now have a work sharing option as part of their unemployment insurance program, the take-up rate on work sharing has been low. In 2009, at the trough of the downturn, just 0.22 percent of workers in the United States were on a state work sharing program. By contrast, the share in both Italy and Germany was more than 3.0 percent, and it was over 5.0 percent in Belgium.[6] Clearly, there is much room for progress.

At the most basic level, just making employers aware of the program would be an important first step. Employers have little knowledge of work sharing even in the states that have this option as part of their unemployment insurance system. Since the decision to use work sharing as an alternative to layoffs is at the option of the employer, they must know about the program in order to take advantage of it.

For this reason, simply publicizing the program could be expected to substantially increase the take-up rates. There are undoubtedly many employers who would welcome the option to keep workers on staff working shorter hours if they knew that the unemployment insurance program could be tapped to share the costs. If the expectation is that a downturn in demand will be temporary than employers can save considerable time and expense in hiring costs and training if they can keep valued workers on the payroll through a downturn.

If a national political figure or governor were strongly committed to promoting work sharing, they could likely substantially boost knowledge of the program simply by arranging a photo op at a business that uses the program successfully. If this were coupled with a larger promotional campaign, it could substantially increase take-up rates for work sharing. For whatever reason, the Obama administration was not interested in promoting work sharing even though it was ostensibly supportive of work sharing as an alternative to layoffs.

A second way in which to increase take-up for work sharing is to modernize the mechanics of the program. Most of the states that have work sharing programs adopted them in the late 1970s or early 1980s. They still have the same rules and systems in place as they did four decades ago. In some cases, systems have not even been computerized so that employers would have to fill out forms on paper to comply with regulations.

Congress did make money available for modernizing these systems in the bill that extended the payroll tax cut in 2012, but many states did not take advantage of the funding. It should be a priority to modernize these systems so that the mechanics of work sharing are no more difficult for employers than laying off workers who then collect unemployment insurance.

There are also rules on work sharing in many states that may discourage the use of work sharing, such as requiring full contributions to health care insurance or pensions. While it may desirable to see workers in work sharing arrangements getting full insurance coverage, workers who are laid off will get none. It is likely to increase the take-up rate if a reduction in work hours leads to a roughly proportionate reduction in labor costs. There is no public interest in encouraging layoffs rather than reductions in work hours.

Another factor that could encourage the use of work sharing is raising the cost of layoffs. This could be done by instituting severance pay requirements. While it is difficult to envision national legislation on severance pay any time in the foreseeable future, states have the option to implement severance pay on their own. Excessive severance pay requirements may be a disincentive for firms to hire in a state, but modest requirements are likely to have little negative impact on employment.[7]

For example, a requirement of two weeks of severance pay per year of employment is unlikely to impose a major cost on employers. This will have the effect of making employers more reluctant to lay off workers in a downturn.

A severance pay requirement, as opposed to dismissal at will, can also have other beneficial effects in redressing the imbalance of power at the workplace. If an employer knows that they would have to pay a substantial price for firing a long-term employee, they would be more hesitant to do so. This would mean workers would be better positioned to challenge abusive practices. This would include efforts to circumvent rules on overtime. Requiring severance pay would also facilitate unionization efforts since employers would need some genuine reason for firing workers involved in an organizing drive if they wanted to avoid severance pay.

Another measure that states could use to promote work sharing is by imposing higher premiums for overtime or even adopting a shorter standard workweek. As with the minimum wage, the federal government creates a floor, not a ceiling. States could opt to make the premium for overtime 100 percent rather than 50 percent. Making it more costly to have workers put in overtime hours, increases employers’ incentive to have some room to spare before hitting the overtime mark. This could mean that employers find it desirable to have workers put in 35 to 38 hours per week so that if they suddenly need additional labor, they can get more hours from their workers without paying the overtime premium.

The steps listed above all involve little or no expense to state governments. However, if a state was especially committed to promoting work sharing, it could structure the system so that it involved a subsidy relative to unemployment insurance. For example, if the standard unemployment benefit is equal to 50 percent of lost pay, the work sharing system can be structured to compensate any reduction in hours at 60 percent of the time lost. This should not involve a large expense, but could substantially increase take-up rates. Also, insofar as low take-up rates are simply due to a lack of familiarity with the program, temporary subsidies of this sort may be sufficient to have a lasting impact on take-up rates.

In the same vein, states can simply offer some prize money for employers that find innovative routes to maintain or increase employment by shortening work time. This sort of prize system could involve a specifically designated sum of money to be awarded over a relatively narrow time frame (e.g., one to two years). The goal would be to create interest among employers in ways to restructure their workplaces so that workers put in fewer hours. The winners of this money would presumably have plans that could be emulated by other employers.

Conclusion: The United States Need Not be an Outlier in Leisure Time

The United States increasingly stands out among wealthy countries for its lengthy work years. While workers in other wealthy countries have long been guaranteed paid sick leave, family leave, and vacation time, these leave policies are only available to better-paid, more secure workers in the United States. There is good reason to believe this difference is more attributable to policy and institutional differences rather than any inherent desire of workers in the United States to sacrifice time off in order to have higher incomes.

Work sharing can be a route to directly lower average hours, which can both have a secular impact on the length of the work year and be a form of protection against cyclical unemployment. Programs for work sharing already exist in most states as part of their unemployment insurance system. This paper suggests policies, some of which involve little or no additional public spending, which could increase take-up rates. This can be an important step in getting the United States more in line with the rest of the world in the length of its average work year.

[1] These data are taken from the OECD. The OECD warns against making comparisons across country, since there are inconsistencies in the methodologies used. However, even if we treat the levels with caution, the changes though time in each country should be comparable. In other words, a 20 percent decline in average annual hours in France should mean roughly the same thing as a 20 percent decline in hours in the United States or Denmark.

[2] There is a different way of posing this issue as one of technological bias, with robots and artificial intelligence primarily displacing less-educated workers, while maintaining or even increasing the demand for the most highly educated workers. This story also has little solid evidence or logic to support it. It is far from clear that technology will have a disproportionate impact on less-educated workers. For example, robots are likely to prove better in the not too distant future than even the best surgeons in performing operations. The advance of diagnostic tools is likely to allow trained professionals to replace the doctors in many circumstances. There are many other examples of situations in which technology is likely to displace some of the most highly educated and highly paid workers in the economy. It is also important to remember that the demand for highly educated workers in many areas depends on the strength and length of patent and copyright monopolies. This point is important because the rules on patent and copyright monopolies are determined by public policy, not technology. If we think that people who get ownership claims to technology are benefitting at the expense of ordinary workers, then this is the result of policy decisions. It is not the fault of the technology.

[3] Neumann, Todd, Jason Taylor, and Price Fishback. 2013. “Fluctuations in Weekly Hours and Total Hours Worked Over the Past 90 Years and the Importance of Changes in Federal Policy Toward Job Sharing.” Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper #18,816.

[4] These data refer to the OECD’s harmonized measure of unemployment, see: https://data.oecd.org/unemp/harmonised-unemployment-rate-hur.htm.

[5] Germany’s unionization rate at start of the downturn was almost 20 percent, compared to less than 12 percent in the United States, see: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TUD.

[6] Abraham, Katharine G., and Susan N. Houseman. 2016. “Proposal 12: Encouraging Work Sharing to Reduce Unemployment.” Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/work_sharing_abraham_houseman.pdf.

[7] Howell, David R. et al. 2006. “Are Protective Labor Market Institutions Really at the Root of Unemployment? A Critical Perspective on the Statistical Evidence.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/documents/2006_07_unemployment_institutions.pdf.