Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

November 19, 2019, Eileen Appelbaum

Testimony by Dr. Eileen Appelbaum, Co-Director, Center for Economic and Policy Research to the House Committee on Financial Services. View video of hearing here.

November 19, 2019

Chair Waters, Ranking Member McHenry and distinguished Members of the Committee. I am pleased to be here today, at this important hearing, to discuss the role that private equity funds and hedge funds play in the U.S. economy today.

By way of background, I am currently the Co-Director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Prior to joining CEPR, I held academic positions as Distinguished Professor (Professor II) in the School of Management and Labor Relations at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey and as Professor of Economics at Temple University. I earned a PhD in economics at the University of Pennsylvania. My co-authored book with Cornell University Professor Rosemary Batt, “Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street,” is a balanced account of private equity that was selected by the Academy of Management – the premier professional association of business school faculty – as one of the four best books published in 2014 and 2015. The book was a finalist in 2016 for the prestigious George R. Terry Book Award.[1]

Private equity funds and hedge funds are structured in a similar manner. They are sponsored by a private equity or hedge fund firm which recruits investors for its funds. A committee made up of partners and principals in the sponsoring private investment firm is the General Partner (GP) of the fund and makes all the decisions. Investors in the fund include institutional investors (pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowments and so on) as well as wealthy individuals. These investors are Limited Partners (LPs) and have no say in decisions about the fund’s financial activities. The LPs put up most of the equity in these funds, with the General Partner typically putting in one to two cents (occasionally as much as 10 cents) for every dollar the Limited Partners contribute. The LPs pay a management fee to the GP (the private investment firm), typically 2% of the money they have committed to the fund. The larger the fund, the larger the no-risk payments to the GP (and thus the private investment firm). The GP also collects a lion’s share of any profits, typically 20% (but may be as high as 30 %) of the fund’s returns.

Private investment funds play a significant role in the U.S. economy. Over the past decade, assets managed by hedge funds and private equity funds have exploded: they have doubled for hedge funds since 2009[2] and septupled for private equity funds[3] since 2007. Global private fund assets exceed $3 trillion for both hedge funds and private equity funds, with about $1.6 trillion[4] of PE assets held in the U.S. A recent study of U.S. companies taken over by private equity funds[5] was able to identify 9,794 buyouts of U.S. companies between 1980 and 2013. The authors were able to confidently match about 6,000 (~60%) of these to information on the companies. These 6,000 companies employed a total of 6.9 million workers in their stores, warehouses, offices, factories, and service operations at the time of the buyout. Hedge funds operate differently, buying up distressed debt or acquiring a small but significant equity stake in large, publicly-traded companies that enables it to dictate business strategies at those companies. Both private equity and hedge funds charge investors high management fees without providing them with transparency or control of the fund’s activities, typically take 20 percent of the profit, and finance their operations with high levels of borrowing that feed a growing market for risky, junk bond corporate debt that is reaching dangerous levels.

Private investment funds capture wealth that enriches the partners in the private equity firms that sponsor them. Partners in these funds can be found in the billionaire ranks of the 0.1 percent of richest Americans. But do these funds create value for the companies they acquire and for the economy? That is the question I want to address today.

Private Equity

A recent article[6] in Institutional Investor, a leading international business to business publication focused on finance, highlights what it called the ‘paradox of private equity’: smaller private equity funds outperform mega funds and tend to deliver the best returns to investors, but the bulk of the money invested in private equity flows to the really large mega funds. Better performance of smaller funds is actually not surprising. In our research, Rose Batt and I found that smaller PE funds typically acquire small and medium-sized enterprises that can benefit from the access to financing and improvements in operations and business strategy that private equity firms can provide. These PE funds use relatively low levels of debt, provide financing to upgrade operations, advise on implementation of modern IT, accounting, and management systems, and appoint board members that can assist with business strategy. These improvements in governance, operations, and strategy create value for the companies and the economy. These acquisitions, which represent the majority of deals by deal count, will not be affected by the Stop Wall Street Looting Act.

But while the large majority of PE deals are carried out by small funds, the bulk of the money raised by private equity flows to large or mega funds. Investors in PE funds have committed billions of dollars to massive investment funds sponsored by a handful of PE firms. The top 300 private equity firms worldwide raised $1.7 trillion between January 2004 and April 2019. Eight of the top 10 are based in the U.S.[7] Despite the fact that their mega funds are a tiny fraction of the nearly 4,000 PE funds[8] that Prequin reports were raising money in 2019, funds of these eight firms raised a total of $354.2 billion – a fifth[9] (21 percent) of all the money flowing into private equity funds in that five year period.

Mega funds have incentives to acquire large companies even if the returns are mediocre compared with smaller companies. A mega fund has a lot of capital it needs to deploy in a relatively short period of time. This is more easily done if the fund acquires a few large companies. The exception is when a PE fund buys up small competitors and adds them onto a large company it already owns, flying below the radar of antitrust regulators as it creates a national powerhouse. PE funds plan to exit their acquisitions in three to five years. This is too short a time horizon to ‘turn around’ a struggling company; in contrast to the myth that PE funds buy troubled companies, attractive acquisition targets tend to be successful businesses. These companies present few opportunities for creating value by improving operations or business strategy. They nevertheless present opportunities for making money for PE firm partners.

How is it possible for a private equity fund to make money without creating value? The place to start is by understanding that the PE fund views the companies it acquires as financial assets in its portfolio – portfolio companies – whose purpose is to provide returns to the fund and its investors, including the General Partner (PE firm). The PE firm also has means to extract wealth directly from the portfolio company.

Let’s begin with the use of debt. Large companies that are attractive targets for a private equity buyout possess considerable assets that can be used as collateral to finance the takeover of the company. A large amount of debt (referred to as leverage) is used to acquire the company for the fund’s portfolio, and it is the company, not the PE fund that owns it, that is obligated to repay this debt. Debt is a double-edged sword. For the PE fund, high debt and little equity means that even a small increase in the enterprise value of the portfolio company translates into a large return to the PE fund. For the portfolio company, however, high debt increases the risk of financial distress or even bankruptcy and liquidation. Private equity is gambling with the future viability of the company when it loads it with debt. It is assuming that the company will be able to service the debt and to refinance it as it matures. In the case of an unanticipated development, however, the company may find its margin of safety has been eroded by debt payments. It may be forced into bankruptcy. The private equity firm will lose at most its equity investment in the portfolio company, and often this has already been repaid via fees the PE firm collects from the company. The PE firm has little to no skin in the game; it’s the company, its workers, suppliers, creditors and customers that the use of leverage (high debt) has put at risk.

For many years, retail was the sweet spot for private equity. Retail is a cyclical business that can be undermined by a change in customer tastes or a downturn in the economy. To weather the inevitable bad times, retail chains typically have low debt burdens and own their own real estate. This protects them from having to pay rent or make high interest payments when things get tough. Retail is also a high cash flow business. These characteristics made retail an attractive target for private equity. There was room to load the company with lots of debt in the buyout. The real estate opened up the possibility of sale-leaseback transactions that benefited PE investors but would leave the chain paying rent. And the high cash flow meant the retail company would be able to make payments directly to the PE firm for advisory services and transaction fees pursuant to an advisory agreement between the chain and the firm. A retail chain that was profitable, but less so than in the past, and whose share price was in the doldrums, was a perfect candidate for a private equity takeover.

Overloading retail chains with debt made them financially fragile. Payments on the debt stripped them of resources they needed to make necessary investments to meet the changing expectations of consumers. The depressed value of commercial real estate following the financial crisis complicated efforts to turnover maturing debt. Financial distress, bankruptcy and even in extreme cases, liquidation and the shuttering of stores are likely to follow. Toys ‘R Us, owned by KKR, Bain Capital and Vornado Realty Trust, is the poster child for this. But there are many other well-known examples of private equity-owned retail chains that closed all stores and laid off thousands of workers. They include Sun Capital-owned ShopKo, Alden Global Capital and Invesco-owned Payless ShoeSource, Bain Capital-owned Gymboree, Sun Capital-owned The Limited, Leonard Green-owned Sports Authority, and Cerberus Capital Management-owned Mervyns Department Store among others.

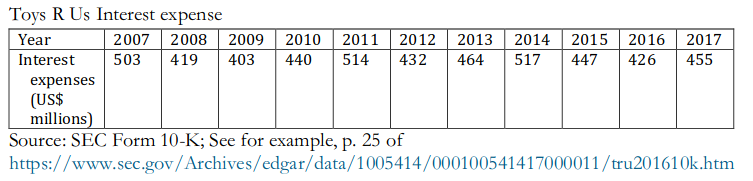

Toys R Us was still profitable at the time of its takeover in 2005 by the KKR, Bain and Vornado consortium, though its sales were flat and its profit and share price had fallen substantially compared with a decade earlier. At the time it was acquired, the toy store chain was valued at about $7.5 billion, including nearly $1 billion in debt. Its capital structure was 87 percent equity and a very manageable 13 percent debt. This was turned on its head when the chain was acquired by the financial firms for $6.6 billion – $1.3 billion in equity contributed equally by funds sponsored by those firms and $5.5 billion in debt. With the almost $1 billion in debt the chain was already carrying, this raised its debt to $6.2 billion- a capital structure of 17 percent equity and 83 percent debt. This is a level of debt no publicly-traded company would burden itself with. It served no rational business need for Toys ‘R Us, which now had to make interest payments on this debt that exceeded $400 million in every year and $500 million in some (see Appendix A for details and sources). But for the investment funds that owned the chain, the low amount of equity they paid in would mean a high return and very rich payoff if they exited the company in three to five years as planned. In 2010, five years after acquiring the company, KKR, Bain and Vornado attempted to return the company to the public market via an IPO. The effort failed however on concerns about the toy chain’s ability to refinance its high debt load.

It is this reckless loading of debt onto companies that the Stop Wall Street Looting Act would end by requiring the PE fund’s General Partner and the PE firm to be jointly liable with the company for repaying the debt it burdens companies with in a leveraged buyout.

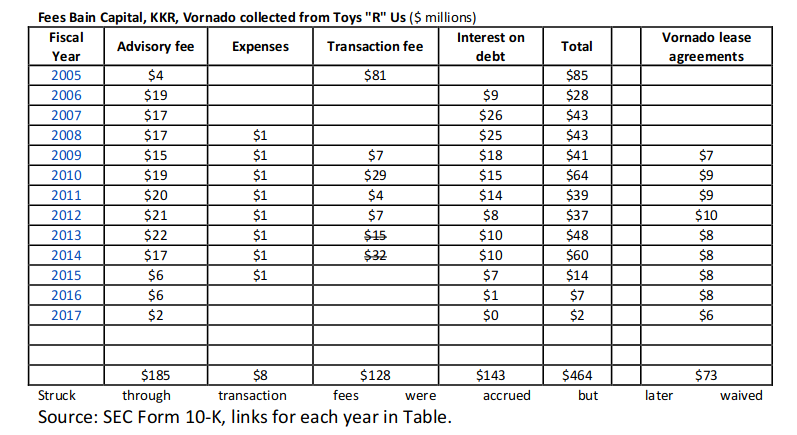

Toys ‘R Us would have been broadly profitable in the years following its takeover by the private investment funds if not for the interest payments, which largely ate up the company’s profits. The chain struggled and ultimately collapsed under its massive debt load. 900 communities lost an important retail anchor as the stores closed, 33,000 workers lost their jobs. The Limited Partners in the PE funds had their investment in Toys wiped out. But KKR, Bain and Vornado managed to make money despite not creating – and, in fact, destroying – value. The funds that owned the chain each put in $433 million in equity each. Bain contributed 10 percent of the equity in its fund or $43 million. KKR put up $10 million (2.3% of the equity in its fund). Vornado’s contribution is unclear. At the time of its acquisition, Toys ‘R Us had entered into an advisory agreement with each of the three sponsoring firms (not the funds) that specified payments that Toys ‘R Us would make to KKR, Bain and Vornado for advisory services. Over the life of the agreement, Toys ‘R US paid Bain, KKR and Vornado a total of $185 million for these services, or $61 million each. Bain did not agree to share these payments with its limited partners so net of its equity contribution, it had a gain of $17 million. KKR had agreed to share 58% of its advisory fees with its limited partners, leaving it with $24 million. Net of its $10 million contribution to its PE fund, KKR had a gain of $14 million. It’s not clear how much of Vornado’s $61 million was a net gain. In addition to the advisory fees, the three companies collected a total of $8 million in expense fees, $128 million in transaction fees, and $143 million in interest on loans they had made to Toys ‘R Us. In total, including advisory and other fees and interest, Toys ‘R Us paid the firms that owned it $464 million. In addition, some of the chain’s real estate was sold to Tornado and leased back by the stores, resulting in a total of $73 million paid to Vornado in rent (details and sources in Appendix A).

So, yes – as the Toys case illustrates, it possible for PE firms to make money without creating value.

Another very different example of how PE firms make money without creating value comes from the world of physician staffing firms.

Surprise medical bills – bills that insured patients receive when they are inadvertently treated by doctors not in their insurance network – have become a flashpoint for Congressional action. Private equity firms have been actively acquiring doctors’ practices through leveraged buyouts and rolling them up into large, debt-burdened physician staffing firms. The focus of private equity acquisitions is on medical specialties such as emergency room doctors, radiologists, anesthesiologists, and neonatal specialists that treat hospital patients with urgent care needs. These patients are in no position to refuse medical attention and must accept treatment from the doctor assigned to them by the hospital. The doctors you have never met who pop up in the doorway of your hospital room to inquire if you are okay – hospitalist doctors – may also be employed by a physician staffing firm and not be on the hospital’s staff. If a patient is in a hospital that is in their insurance network, they may reasonably assume that the doctors working at the hospital are in their network as well and that any bills will be covered by their insurance plan. But this is not necessarily the case. The hospital may have outsourced these specialties to local doctors’ practices or to major physician staffing firms. The result is that these doctors – who were assigned by the hospital to care for the patient, and not selected by the patient – may not be in-network and the patient may receive a surprise bill. Demand for these doctors’ services is not sensitive to price and does not go down because the price is high.

The two largest physician staffing companies are Envision Healthcare and TeamHealth, currently owned respectively by funds of private equity firms KKR and the Blackstone Group. The two staffing firms have cornered 30 percent of the market[10] for outsourced doctors, and collectively employ almost 90,000 health care professionals that staff hospitals and other facilities across the U.S. Envision is the result of fifteen years of private equity transactions using debt to buy up and consolidate emergency room and specialty physicians’ practices. In and out of private equity ownership since 2005, Envision most recently was acquired by a KKR fund. TeamHealth grew not only through leveraged buyouts of specialty doctors’ practices but via the acquisition of a very large staffing firm that had consolidated many hospitalist doctors’ practices. The company has experienced successive rounds of leveraged buyouts by Blackstone funds, punctuated by IPOs that returned it to the public markets, only to be taken private again. It is currently owned by Blackstone. Many of the acquisitions by both PE-owned companies were too small to trigger anti-trust oversight. The result is two highly consolidated physician staffing firms that are national powerhouses. Both firms are heavily indebted and rely on high fees they charge for doctor services to provide sufficient revenue to meet debt obligations.

Envision has come under heavy scrutiny for the huge out-of-network surprise medical bills it sends to ER patients. A team of Yale University health economists[11] examined the billing practices of EmCare, Envision’s physician staffing arm. They found that when EmCare took over the management of hospital emergency departments, it nearly doubled its charges for caring for patients compared to the charges billed by previous physician groups. TeamHealth, according to the analysis by the Yale University economists, has taken a somewhat different tack. It uses the threat of sending high out-of-network surprise bills to an insurance company’s covered patients to gain high fees from the insurance company as in-network doctors. TeamHealth emergency physicians might go out-of-network for a few months, then rejoin the network after bargaining for in-network payment rates that were 68 percent higher than in-network rates received by the previous ER doctors. While this avoids the situation of a patient getting a large, surprise medical bill and allows Blackstone to say its staffing firm doesn’t engage in surprise billing, it is clear that TeamHealth’s business model relies on the threat of going out-of-network to get higher reimbursement rates for its doctors. And, in any case, TeamHealth’s practices raises healthcare costs and premiums for everyone. Meanwhile, UnitedHealth, the largest U.S. health insurer, is pushing back. It plans to end high-reimbursement in-network contracts with TeamHealth over the next few months. TeamHealth may sue to prevent this.

Here again we have an example of how private equity firms make money without creating value. PE-owned firms Envision and TeamHealth have consolidated a previously fragmented sector, doctors’ practices. They are now dominant players and are exploiting their market power to increase prices. In this way they are able to capture wealth from patients, rather than creating it.

Pushback from patients has led Congress to consider acting to protect them. In early summer, bipartisan legislation was introduced in the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee (the Lower Health Care Costs Act)[12] and in the House Energy and Commerce Committee (the No Surprises Act).[13] The approach in both bills involves capping what is paid to out-of-network doctors by ‘benchmarking’ payments to rates negotiated with in-network doctors. This would threaten the private equity business model in owning doctors’ practices; it is opposed by specialist physician practices[14] and by large physician staffing companies. They are lobbying intensively[15] for a second option that would allow doctors to seek a fee higher than the benchmark via an arbitration process. Physicians for Fair Coverage,[16] a private equity–backed group lobbying on behalf of large physician staffing firms, launched a $1.2 million national ad campaign[17] in July to push for this second approach. The campaign was effective and the House bill was amended to include an arbitration provision.

The arbitration amendment did not go far enough to satisfy debt markets that have been closely monitoring developments.[18] Envision Healthcare’s $5.45 billion loan due October 2025 and Team Health $2.75 billion loan due January 2024 fell in July and dipped below 80 cents on the dollar by the end of August[19] – the threshold for a loan to be considered distressed. In late July, a mysterious organization, Doctor Patient Unity, launched a $28 million ad campaign aimed at preventing any legislation from passing. In September it was revealed[20] that Envision Healthcare and TeamHealth were behind the effort to stop legislation that threatened their business model.

In November, with the legislation and chances of passing legislation to rein in surprise bills in this Congress stalled, the loans have recovered somewhat. Envision’s loan is holding steady in the low 80s and TeamHealth’s in the mid-70s. But the legislation has bipartisan support and is expected to be reintroduced in 2020 or 2021. The intense lobbying and massive ad campaign may have backfired. The Energy and Commerce committee has demanded information on pricing practices[21] from KKR, Blackstone and Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe. Senator Warren and Representatives Mark Pocan and Lloyd Doggett are seeking similar information[22] from these and two additional private equity firms about the role they are playing when patients receive exorbitant surprise bills. Legislation to cap out-of-network fees charged by doctors’ practices will save patients who urgently need care from outrageous charges and will reduce health costs and premiums for all consumers.

Hedge Funds

Hedge funds are another type of private investment fund with a model for making money that differs from the private equity model. In general, most of private equity activity involves buying out companies and taking them private while hedge funds pursue profits through the purchase and sale of stock in publicly-traded companies. As was true of large private equity firms, hedge fund firms have found many ways to make money – the very top hedge fund managers make more than a billion dollars a year – without creating value.

In 1940, New Deal legislation was passed to protect Main Street companies and the economy from the speculative financial practices that generated the Great Depression. The legislation prohibited firms operating with pools of money drawn from investors from engaging in a range of risky practices. Wealthy families with their own private investment funds and fund managers were able to get an exemption for fund advisors with fewer than 100 clients who didn’t offer services to the general public. In less than a decade and taking advantage of that exemption, the first hedge fund was formed. Still, by 1997, hedge funds worldwide held just $118 billion in assets[23] under management. Then in 1996, as part of a general move to deregulate financial services, Congress passed the National Securities Market Improvement Act which extended the exemption for fund advisors from 99 to an unlimited number of ‘qualified purchasers.’ This opened the door to institutional investors to become investors in hedge funds. Hedge fund assets under management quickly increased, and today they top $3 trillion worldwide.

How do hedge funds make money?

As with private equity funds, the high fees they charge limited partner investors in their funds and the lack of transparency about these fees are a steady source of income to partners in hedge fund firms. But it is the risky activities they carry out – all of which are prohibited in the New Deal era legislation from which they are exempt, that are the source of outsized earnings of hedge fund firm partners. Unlike mutual funds whose activities are governed by the restrictions against risky activities, hedge funds are able to engage in short sales (bets that a stock will go down instead of up), use leverage (debt owed to lenders) that magnifies returns but also increases risk, and take over the business strategy of corporations.

Activist hedge funds buy up shares in a publicly traded company and accumulate sufficient shares to pressure corporate managers and boards of directors to take actions that, at least in the short run, boost share price. This includes threatening to shake up companies in order to persuade them to carry out share buybacks, spin off parts of the company, or initiate some other major change.

Stock buybacks are a favorite hedge fund tactic for raising share prices and allow the hedge fund to cash in and sell its shares at a profit. The effect on the company and its workers are of no concern to the hedge fund. In 2015, four hedge funds that owned 2.1 percent of GM shares,[24] led by Appaloosa Management, used harassing proxy fights and public threats to pressure GM to buy back $8 billion of its shares within a year. In March 2015, the company announced it would buy back $5 billion of shares. Later that year, it announced another $4 billion of buybacks. And in 2017, it announced it would buy back an additional $5 billion. By November 2018, GM had spent $10.6 billion on stock buybacks.[25] The hedge funds contributed nothing to creating value for GM, but they walked away with millions of dollars from the buybacks. The money GM spent on buybacks is double what the company will save by laying off up to 14,000 workers and closing five automobile facilities, including the Lordstown Assembly plant, which likely fell victim to a lack of investment as the company used its profits[26] for the payouts the activist hedge funds demanded. More generally, share buybacks enrich hedge funds, but they force companies to cut back on investment, research and development, and job creation. Share buybacks used to be illegal; Senator Tammy Baldwin has introduced legislation to make them illegal again.

Paul Singer’s Elliott Management is another activist hedge fund noted for the hardball tactics it uses to extract short run profits from major companies. In early September 2019, the hedge fund announced it had taken a $3.2 billion stake (a 1% share) in $281 billion telecom and media giant AT&T.[27] Elliott demanded[28] a number of value-extracting initiatives at AT&T. These included carrying out stock buybacks, increasing dividends, monetizing (i.e. selling off) some of its assets, and laying off workers. Elliott also wanted to appoint two directors to the AT&T board. Seven weeks after Elliott made these demands, AT&T capitulated.[29] It committed to buying back stock, adding two new directors, and looking at its assets to see what could be jettisoned. AT&T expects to have sold off about $14 billion worth of companies it owns in 2019, and another $5 to $10 billion in 2020. AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson noted that AT&T’s strategy to increase profits includes potential job cuts.[30] The Communication Workers of America (CWA) which represents over 100,000 AT&T workers strongly opposes the job cuts. The union estimates that meeting Elliott’s demand will put 30,000 of its members jobs at risk. It notes that profits that will now be used for stock buybacks could be better spent by the company “to increase investment in next generation wireless and fiber broadband networks and train its employees for jobs of the future.”[31]

Almost everything in the agreement between Elliott and AT&T is focused on raising AT&T’s share price in the short run. It’s not clear how increasing stock buybacks and dividends prepares AT&T to succeed in the future. Moreover, AT&T gave in to Elliott’s demands without getting a ‘stand still’ agreement that commits the hedge fund to not make additional demands. With the outcome for GM and its workers still fresh in everyone’s minds, the fear that these measures will enrich Paul Singer and Elliott’s investors at the expense of AT&Ts workers is very real.

A company that uses its profits to manipulate its share price – buying back shares so that the number of shares goes down and their price goes up – is failing its customers and employees because these are funds that could have been used to upgrade and improve the company’s products and operations. Share buybacks enable hedge fund investors (as well as other shareholders) to make money without creating value for the company and, indeed, jeopardizing the company’s future value creation and the employment of its workers. Prior to the Security and Exchange Commission’s adoption of Rule 10b-18 in 1982, stock buybacks were recognized as a form of market manipulation and were illegal. In March 2019, Senator Tammy Baldwin reintroduced the Reward Whttps://www.baldwin.senate.gov/press-releases/reward-work-act-2019ork Act.[32] Specifically, it would repeal Rule 10b-18 and remove the incentive for hedge funds to demand stock buybacks by companies in which they own shares just to raise share price.

Elliott Management had a significant role in closing down a different major company in the U.S. and sending 25,000 jobs to China. Distressed debt hedge funds look for corporations or nations in financial trouble, buy up their bonds at pennies on the dollar, and then use their position as creditors to secure a high return for themselves. After auto parts maker Delphi,[33] a supplier to GM, declared bankruptcy in 2005, a group of hedge funds led by Paul Singer’s Elliott Management bought up Delphi’s debt, some for as little as 20 cents on the dollar. In 2009, during the financial crisis, when the U.S. Treasury was working on a deal to save GM, Treasury and the company came up with a plan to save Delphi. PE firm Platinum Equity offered to buy Delphi, and GM and Platinum came up with an arrangement that would have kept most of Delphi’s plants open and saved most of the jobs. In the meantime, Elliott Management tripled its acquisition of Delphi’s bonds. The creditors, led by Elliott, persuaded the bankruptcy judge to hold an auction. Platinum lost its bid to buy Delphi to a higher bid by Elliott and the creditors. The new owners quickly closed most of the plants and sent the work to China, along with 25,000 union jobs. Two years later, the consortium of creditors returned Delphi to the public markets via an IPO. Without its pension and health care liabilities, and with its debt substantially reduced, Delphi traded at $22 a share at its IPO[34] – resulting in a profit of more than 3,000 percent for Elliott and the group of creditors. Now known as Aptiv, the company is incorporated in the tax haven, Jersey – depriving the Treasury of needed tax revenue. Elliott Management made a lot of money, not by creating value but by destroying value for Delphi’s American workers and the U.S. economy. Provisions of the SWLA that direct bankruptcy courts, where there are multiple offers, to approve the offer that best preserves the company’s jobs and maintains the terms and conditions of employment for its workers, will prevent this from happening again.

Pressuring companies in which they own shares to strip assets by selling off the real estate that houses their operations is another hedge fund tactic. In 2014, Starboard Value – a shareholder in restaurant company Darden, the parent of Olive Garden and many other restaurant chains – noted that Darden owned both the land and buildings on nearly 600 of the restaurants and the buildings of another 670. Starboard estimated the value of Darden’s real estate at $2.5 to $3 billion, and argued that a sale-leaseback of the properties “could create approximately $1 billion in shareholder value.”[35] Unable to persuade Darden’s management and board to sell off the real estate, Starboard made good on its threat to replace the Darden board with its own slate of board directors. Soon after, the new board forced Darden to monetize the value of its restaurants’ real estate[36] to the benefit of shareholders. This exercise in financial engineering enabled the hedge fund to make money, but financial engineering doesn’t create value.

The case of DuPont – once a giant chemical and agricultural company is a cautionary tale of how hedge fund activism to raise share price can undermine America’s scientific prowess. In 2013, Nelson Peltz’s $11 billion hedge fund firm Trian Fund Management took a $1.3 billion stake[37] in DuPont, bringing its share of the company to 2.2 percent. By early 2015, Trian was ready to push DuPont to split into two companies38] – an agriculture and nutrition products company and a materials company – and to dismantle its research and innovation center and end programs that allowed the company’s 1,000 scientists and engineers to work together. Trian’s push for change at DuPont came despite a doubling of the company’s share price under CEO Ellen Kullman. Trian lost its bid for seats on DuPont’s board, but in the months that followed, it looked as if Trian might have won anyway.[39] Kullman soon retired and her successor made it clear he was open to Trian’s ideas.

In December 2015, DuPont announced it would be merging with the Dow Chemical company[40] and would later be broken up into an agricultural company, a specialty products company, and a material sciences company. DuPont would be laying off 1,700 workers, including nearly half the scientists at the Experimental Station, its famous research center – a bad omen for future innovation. The merger closed in August of 2017; the spinoff of new Dow (material sciences) occurred in April 2019 and of Corteva (agriculture) in June of that year. Trian wasn’t sticking around to see how things worked out. It began reducing its stake[41] in the fourth quarter of 2015, and by December 31, 2017[42] it had disposed of the last of its shares. Early results of the merger and split were not good. In May 2019, the combined shares of Dupont/Corteva and new Dow were worth significantly less than the $150 billion the company was worth[43] when the merger and splits were first announced.

A number of initiatives in addition to the SWLA could help rein in the excesses of hedge fund firms. Most important would be rolling back section 209 of the National Securities Market Improvement Act that removed any limits on the number of investors a hedge fund could have and still be exempt from strict rules that reduce risky, speculative financial activities. This would return hedge funds to their original purpose – managing the money of the wealthiest U.S. families. It would end the activist funds’ ability to extract wealth out of Fortune 500 companies and destroy jobs, and to make billions of dollars for hedge fund firm partners without creating value. The Reward Work Act would make stock buybacks and manipulation of share prices illegal again, as they were prior to 1982. The common-sense provisions of the Brokaw Act – named for a small Wisconsin town that went bankrupt after Starboard Value bought a paper company and then closed the paper mill in Brokaw – would end financial abuses by activist hedge funds. The Brokaw Act[44] was first introduced in March 2016 by Senator Tammy Baldwin and reintroduced in 2017. It would reduce opportunities for investors in public companies to evade rules that govern disclosure requirements when hedge funds and other investors buy a 5 percent stake in a company’s stock. The bill would also require that hedge funds that use derivatives to amass a larger stake in a company will have to include these derivatives in their disclosures.

Conclusion

In ways large and small, Main Street is being pillaged by Wall Street’s largest private investment firms. Factories and stores have closed as wealth has been extracted from companies, hollowing them out and leaving them bereft of the resources they need to invest in technology and worker skills. Money has been funneled to millionaire and billionaire partners in these firms even when their firms do not create value and, indeed, may destroy it. Good jobs have been lost and inequality has worsened. Private investment firms take advantage of loopholes in laws and regulations that are not available to other financial actors to engage in the types of self-serving behavior documented here. It’s time to close these loopholes and bring private equity and hedge funds under the same regulatory umbrella that limits risky behavior by other financial institutions. Passage of the Stop Wall Street Looting Act would go a very long way toward accomplishing this aim. Rolling back the National Securities Markets Improvement Act is another important step that needs to be taken. Legislation to halt particular financial abuses – hitting vulnerable patients with surprise medical bills, manipulating stock prices via share buybacks, or organizing ‘wolf packs’ to skirt reporting requirements while accumulating shares in publicly-traded companies – will also be necessary. Such legislation will reduce opportunities for financial abuse and assure that capital is deployed in support of economic development and rising living standards for working families.

[7] The 8 U.S. PE firms that are among the 10 largest PE firms in the world are (in rank order), Blackstone, The Carlyle Group, KKR, Warburg Pincus, Bain Capital, Thoma Bravo, Apollo Global Management, and Neuberger Berman Group.

[17] https://khn.org/news/doctors-argue-plans-to-remedy-surprise-medical-bills-will-shred-the-safety-net/

[30] https://seekingalpha.com/article/4300238-t-settles-elliott-management-big-deal

[33] For discussion of Delphi and Elliott Management, see https://www.russellsage.org/publications/private-equity-work

[44] https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/1744/text

APPENDIX A: Toys ‘R Us Financial Data