Article

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

The Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) in Washington, D.C. aims to provide affordable housing and economic opportunities to underserved households and communities through its housing development projects. One of the three strategic objectives listed by DHCD is “…revitalizing neighborhoods, promoting community development and provide economic opportunities.” Like other large cities across the US such as Boston, New York, and San Francisco, Washington D.C.’s government and its stakeholders are placed with a difficult task to secure space for their communities as their cities accommodate an influx of young professionals, and as a commentator recently pointed out “…[t]hese new District residents have undeniably changed the demographic makeup of D.C., which on the whole has become whiter, wealthier, and younger over the past decade.”

By some indicators, D.C. exemplifies the displacement of people of color to a level that is explicitly contradictory to the city’s stated objectives.

Public-private residential development around the city has contributed to unsustainable rent hikes, gentrifying neighborhoods and causing displacement. Private companies push forward luxury apartment development and retail spaces that ignore the needs of the greater Washington community and the many hurdles it faces towards reaching racial and socioeconomic equity.

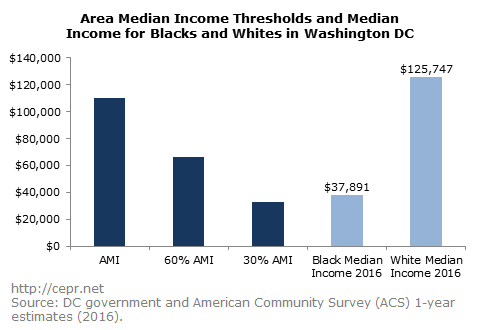

Part of the District’s affordable housing strategy has focused on mixed-income developments which secure affordable housing units, usually by allocating a third of all units to 60 percent Area Median Income (AMI) and another third to 80 percent AMI households. Those that make 30 percent AMI or lower are considered Extremely Low Income (EMI) and those with 50 percent AMI are considered Very Low Income (VLI) according to the Department of Housing and Community Development. However, as the graph below shows, AMI in Washington D.C. is $110,300 — an amount considerably higher than the black median income in D.C.

Black median income in 2016 was $72,409 below the AMI and just $4,801 above the 30 percent AMI. On the other hand, white median income surpassed the AMI by $15,447. White median income is well over three times the median income of blacks. This raises the question of the appropriateness of racially agnostic government policies when it comes to affordable housing.

Additionally, the Washington, D.C. region includes areas outside of the District proper, including Alexandria, Arlington, and Prince George’s county. Cities and suburbs outside of the District that tend to have higher median incomes, drive up the AMI of D.C. and set standards for future development projects which tend to reserve units for households that make 60 percent and 80 percent AMI. Thus, the AMI’s standards are priced too high for a large portion of black households in D.C. Although race-specific thresholds may not be politically effective or feasible, other methods such as lowering the 30 percent threshold, perhaps to 20 percent or less, could more adequately address the populations that the city aims to serve.

Beyond this, pursuing a mixed-income model might lead to other problems. A 2017 publication by the Georgetown University highlights the tangential effects of mixed-income housing:

“Since the 1990s, gentrification has more often been characterized by a state-led effort in partnership with outside developers, wherein government policy has promoted the demolition of public and low-income housing and invested in ‘redevelopment’ through ‘mixed-income housing’ in more affluent neighborhoods.”

The report continues to mention the HOPE VI program and its role in mixed-income housing, which was a national program to revitalize housing development projects:

“Created in 1992, HOPE VI offers funding to cities for the redevelopment of existing public housing into mixed-income units. This program aimed to address the issue of concentrated poverty within inner cities, but instead may have caused the displacement of low-income individuals through the loss of existing affordable units without one-for-one replacement…Only between 14 percent and 25 percent of displaced residents return to their original neighborhood to occupy a new mixed-income unit.”

Thus, there exists both a social and an economic cost of focusing on mixed-income housing which is often ignored.

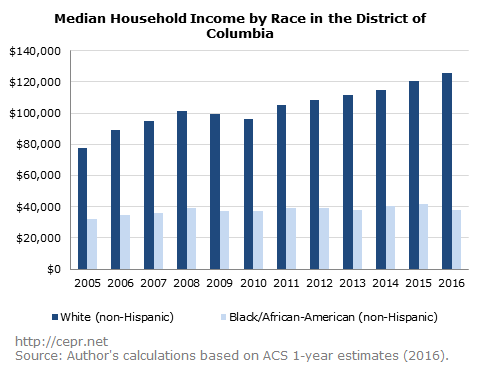

Shown below is median household income by race in the District of Columbia. From 2005 to 2016, black median household income increased by $5,531. On the other side, white median household income has increased by $48,213. In a relative sense, the 17.1 percent increase in black households from 2005 to 2016 is very positive as household income has generally increased quite a bit. However, the comparative median household income shows that whites have gained much more than blacks during this time period. Nationally, from 2005 to 2016, both median white and median black household income within each respective race increased about 25 percent, a figure much lower than D.C.’s 62 percent increase in median white household income, and higher than the 17.1 percent increase that median black households saw during this period of time.

Substantial increases in median income for both blacks and whites during this period highlight the successes of development in D.C. However, the benefits of development alone do not ensure equitable growth and economic opportunity across racial lines. A D.C Fiscal Policy Institute report showed that in 2013, 64 percent of those making 30 percent AMI were rent burdened – meaning that they spent at least 30 percent of their income on their rents. Given this, social policies that help to offset other increasing costs of living, such as subsidized health care, child care, minimum wage hikes and reduced transportation costs, might help to lift the rent burden that inhibits advances in wealth as well as income. Supporting policies like these might have greater effects on communities in D.C. that face additional economic difficulties accumulating wealth and adjusting to a changing city demographic.

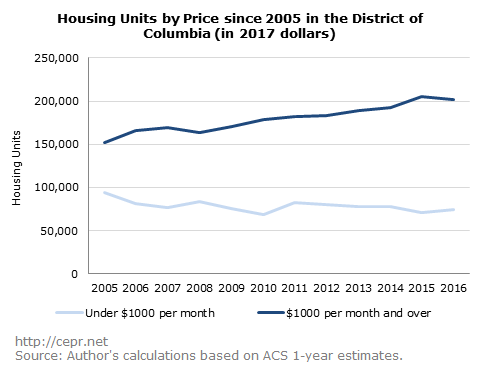

Shown above is a graph of monthly housing costs divided into two groups, one being housing units below $1,000 per month and the other, monthly housing costs at $1,000 or over. The number of units with monthly housing costs over $1,000 has increased by 50,461, and the number of units with housing costs under $1,000 has decreased by 20,234. Data such as these indicate the upward push of the housing market, putting pressure on those whose wages may not be able to keep up with rising housing costs.

Other arguments used to justify the high rents in D.C. include the historic building height restrictions which hamper more construction. However, this story is much more complicated than this factor alone could explain, as discussed.

The D.C. government must acknowledge that its current policies have failed to meet their stated goals. This requires a change of policies; a change to reflect economic realities and the explicit racial divisions in the area. Stronger conditions must be put on developers to secure housing for low-income communities of color.

If the D.C. government does not act in substantial ways to address these problems, it should be held accountable for the damage that their economic partnerships and lack of support for low-income communities of color have caused.