Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

(This post originally appeared on my Patreon page.)

This summer, the Business Roundtable, a group that includes most of the country’s largest corporations, made big news. It issued a statement that its members would no longer be concerned exclusively with maximizing returns to shareholders. Instead, Roundtable members would take into account the well-being of their workers, the communities in which they do business, and the environment.

This statement was given a mixed reception. While some applauded the idea of moving away from a single-minded focus on shareholder value others questioned the sincerity of the commitment. After all, drug companies pushing opioids, oil companies lying about fossil fuels, and hotel and retail chains cheating workers out of their pay, always had the option to do the right thing, but chose not to. Did anyone believe this resolution from the Business Roundtable would change the way they operate?

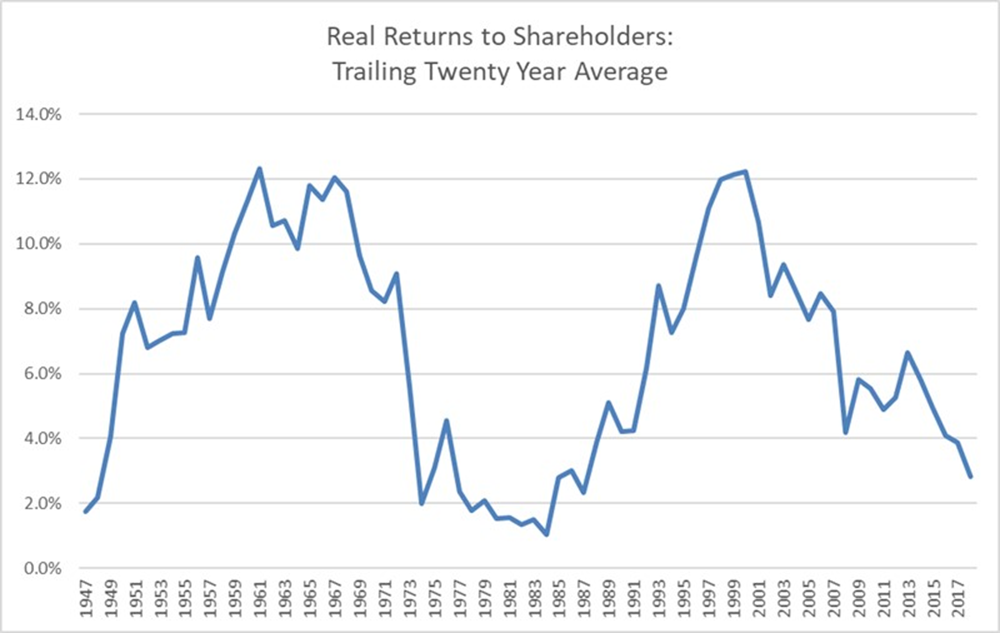

However, there is a more basic point that got almost no attention. There is little reason to believe that corporations are being run to maximize returns to shareholders. The reason for questioning this claim is that returns to shareholders have actually been low by historical standards in the last two decades, as shown in the figure below.

Source: Shiller 2019 and author’s calculations.

The average real return over the last two decades has been just 2.8 percent annually. This compares to average returns of more than 7.0 percent, and sometimes in the double-digits, in the 1950s and 1960s, when corporations were supposedly less single-mindedly pursuing shareholder value. And, this weak return required considerable help from the government in the form of sharply lower corporate tax rates.

The data are very clear. If corporations are being operated to maximize returns to shareholders, they are failing badly in their efforts.

If corporations are not actually maximizing returns to shareholders, then what are they doing? Larry Mishel and Julia Wolfe, at the Economic Policy Institute, recently did an analysis of CEO pay. It found that pay had risen by 1008 percent since 1978, after adjusting for inflation. Average CEO pay for the companies they examined was $14.0 million in 2018 using a conservative method of valuing stock options. If we assess pay using the realized value of the options, average pay was $17.2 million in 2018.

CEOs often justify this compensation by the returns they produce for shareholders. But the data show that they have not been producing high returns for shareholders. Shareholders are doing much worse in the period when corporations are supposed to be maximizing shareholder return than they did in the post-war Golden Age, when unions were strong and workers shared in the gains from growth. This means that today’s CEOs are producing considerably lower returns, but getting paid far more money.

While these basic facts are indisputable (the data on returns are taken from S&P 500, as compiled by Robert Shiller, the data on CEO pay come from the Compustat data base), they are not widely known. Most people seem to believe that corporations really are being run to maximize returns to shareholders.

The persistence of this fantasy is difficult to understand. Conservatives certainly have a reason to maintain this fiction. It is arguable whether a world in which corporations maximize returns to shareholders will give the best outcomes, but this is a much easier case to sell than a world where the CEOs and other top management are maximizing their own paychecks.

This means that the right has a reason to perpetuate this fiction, but why does it persist on the left? I have not carefully monitored the leading progressive publications over the last ten or fifteen years, but I would guess that not one of them has featured a single piece making the point that returns to shareholders have actually been historically low in recent years. Given the importance of this point to the way the economy works, the issue might have been worth a couple of pages somewhere over the last decade.

This is not just a question of good housekeeping or semantics. The excessive pay for CEOs has a massive impact on pay structures both in the corporate sector and in the economy more generally. If the CEO is getting $17 million, then the chief financial officer and other top tier executives are likely getting in the neighborhood of $10 million. The next tier might well be getting $2 to $3 million.

These exorbitant pay scales also affect pay outside the corporate sector. It is now common for university presidents and heads of major non-profits to get well over $1 million a year, and outliers can get pay of $2 to $3 million. The next echelon of executives at these non-profits can get pay in the high six figures.

And, as we learn from economics, more money at the top means less money for everyone else. Suppose CEOs still got 20 to 30 times the pay of a typical worker instead of 200 to 300 times. If we had a world where CEOs of major corporations were earning $2 million a year, then the other top executives would likely be earning around $1.5 million, the next tier may not even cross $1 million.

The president of Harvard, and other elite institutions in the non-profit sector, would likely be looking at pay in the high six figures. There would be corresponding reductions in the pay for provosts, vice-presidents, deans and other top administrators.

In short, the world where CEO pay scales were back where they were forty years ago would have a very different income distribution than the world we see today.

This is why attacking the myth of maximizing shareholder returns is so important. If it really is the case that CEOs produce returns to shareholders that justify their $17 million salary, then they have a rationale for their outsized paychecks. We can attack the idea that the economy and society are best-served by corporations maximizing returns to shareholders, but at least this is a serious position. But if CEOs are not maximizing returns to shareholders, but rather only maximizing their own paychecks, they have a much more difficult argument to make.

I realize that siding with shareholders on anything may rub progressives the wrong way, but we need to look at issues with clear eyes. After all, it’s hard not to side with Jeff Bezos, the world’s richest person, if Donald Trump is denying Amazon a Defense Department contract to punish Bezos for the way the Washington Post covers him.

We all know that stock ownership is hugely skewed towards the rich. But there are middle income people who are relying on their stockholdings for much of their retirement income. In addition, traditional pension funds hold trillions of dollars of stock. Middle class stockholders and workers receiving pensions will both benefit from having less money paid out to CEOs and top executives.

By contrast, every dollar of CEO pay is going to someone in the top 0.01 percent of the income distribution. Insofar, as income is transferred from this group to shareholders in general, it should be seen as a positive for society.

But the bigger picture is far more important than getting a few additional dollars for shareholders. If we can get CEO pay down to anything like its levels of four or five decades ago, the spillover effects on the pay on other top executives (both in the corporate sector and elsewhere) will be enormous. We would be looking at a very different economy and society.

For this reason, it makes sense to make common cause with shareholders in efforts that will allow them to put downward pressure on the pay of CEOs. We should want CEOs to be treated just like all the front-line workers who have seen pay and benefit cuts over the last four decades. If someone else can do the same job for less money, then the CEO will have to live with lower pay or find a new job.

I have written about ways to give shareholders more power to rein in CEO pay (see Rigged, chapter 6 [it’s free]). I’m sure others who are more knowledgeable about corporate governance have better ideas.

Progressives may look at such proposals and decide that reining in CEO pay is not the best use of their time given so many urgent priorities. That is understandable, but one thing that is absolutely not understandable is claiming that corporations are being run to maximize returns to shareholders. That is not true and the people making the claim are either ignorant or deliberately trying to deceive their audience.