Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Inflation: There’s Good News Today!

Article • Dean Baker’s Beat the Press

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

Okay, I have not become an evangelical Christian, but I am still not ready to throw in the towel on the likelihood of sustained inflation. To be clear, there is no doubt that the September CPI was bad news.

You have to dig pretty deep in that report to find much evidence of inflation slowing. We knew some of the numbers would be bad by construction. BLS has done very good research showing how its rental indexes lag private indexes of marketed units. This means that even if rental inflation was slowing in September (this is what the private indexes show), the CPI index would still be reflecting the rapid increases we saw in the market indexes this spring.

Similarly, the health insurance index, which rose 2.1 percent in September, and has risen 28.2 percent over the last year, is based on the gap between insurers’ premiums and what they spend on care. This also lags considerably. The sharp rise in the index reflects a large drop in health care spending during the pandemic. This will likely be reversed in the months ahead, but in the meantime, this component is a big contributor to inflation in the CPI.

But having an explanation for the bad news doesn’t make it good news. We can reasonably expect inflation in the rental indexes to moderate and the health insurance index to turn negative, but for now they are still telling pretty bad stories.

The real disappointment in the September data is that we still have not seen much improvement in the areas where supply chain problems were big factors in pushing up inflation over the last year and a half. There were some good signs, but not much.

Used car prices fell 1.1 percent, but they are still up by more than 50 percent from the start of the pandemic. The appliance index fell 0.3 percent in September, its third consecutive decline. However, appliance prices were still up 13.3 percent from the pre-pandemic level. They had been falling before the pandemic. Apparel prices, which had also been trending downward before the pandemic, fell 0.3 percent, which left them up by 5.5 percent year-over-year (YOY).

Prices continued to rise in other areas where we had seen supply chain issues. Most notably, new vehicle prices rose 0.7 percent, putting their YOY increase at 9.4 percent. The index for car parts and equipment was up 0.8 percent in September, bringing its YOY rise to 13.4 percent year-over-year. And, the price of store-bought food increased 0.7 percent, putting the YOY rise at 13.0 percent.

In short, there was not much evidence of slowing inflation here. The picture looked pretty bad in most major sectors and also most of the minor ones.

Nonetheless, there are still reasons for thinking that inflation will not remain high going forward. My big three are:

Expectations

Taking these in turn, the point on expectations is straightforward. The story of the 1970s inflation was that people came to expect inflation. This led workers to push for higher pay increases. Businesses were more likely to grant them, since they believed that they could quickly recover higher costs with higher prices. This made it harder to push inflation back down to more acceptable levels, since high rates of expected inflation effectively became self-perpetuating.

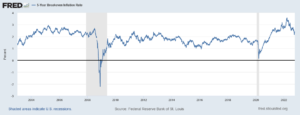

We have a very different story at present. Expectations of inflation, whether measured by surveys like the University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index or financial markets through breakeven inflation rates on indexed Treasury bonds, have come back down to pre-pandemic levels, after rising at the end of 2021 and start of this year. (It is worth noting that the even at their peak, inflation expectations were only up by around a percentage point from pre-pandemic levels. This was nothing like what we saw in the 1970s.)

The reasons for the drop can be debated. Perhaps the decline is a vote of confidence in the inflation-fighting commitment of the Fed. In the case of consumer sentiments, it’s likely that three months of falling gas prices played an important role. Whatever the cause, of the drop, the fact that people are not expecting high inflation to persist is undeniable.

Related to this issue, we never saw a pattern of wage growth acceleration remotely comparable to what we saw in the 1970s. The pace of wage growth did increase sharply in 2021, even if we control for issues raised by changes in the composition of employment. However, since peaking at the end of the year, it has slowed sharply in 2022.

Taking my preferred measure, of annualizing the growth in wages from one three-month period to the next three-month period, wage growth peaked at a 6.1 percent annual rate at the start of this year. In the most recent three-month period (July, August, September) compared with the prior three months (April, May, June), wages grew at a 4.8 percent annual rate. That is too fast to be consistent with the Fed’s 2.0 percent inflation target, but the direction of change is clear, wage growth is slowing, not accelerating.

In fact, if we just look at the last two months, the average hourly wage has increased at a 3.6 percent annual rate. As I always point out, the monthly data are erratic and subject to revisions, so we surely would not want to put a lot of weight on these data just yet. Nonetheless, there is at least a possibility that they are accurate. A 3.6 percent pace of wage growth is in fact consistent with the Fed’s inflation target. Wages grew at a 3.4 percent rate in 2019, when inflation was comfortably below 2.0 percent.

In any case, it is clear that we are not seeing the pattern of accelerating wage growth, pushing inflation higher, that we saw in the 1970s. This should mean there is less urgency in pushing inflation down.

Import Prices

The Bureau of Labor Statistics released its report on September import and export prices the day after the CPI. It received almost no attention. This is unfortunate, because it does tell us a great deal about inflationary pressures facing the economy.

While the CPI was worse than expected, the import price data for September was better than expected. The overall import price index fell by 1.2 percent in September. This was driven largely by a 7.5 percent drop in the index for imported fuels, but even pulling this out, import prices dropped by 0.4 percent in September, the fifth straight monthly decline. This means that the prices for a wide range of items that we import, like clothes, cars, appliances, and thousands of other goods and services, are now falling.

This is a big deal. Since May, the non-fuel import price index has fallen by 2.0 percent. This is a 4.7 percent annual rate of decline. By contrast, in the years from May 2020 to May 2021, this index rose by 6.1 percent, and by 5.9 between May 2021 and May 2022. The story here is that the prices of a wide range of imported goods had been putting upward pressure on inflation until the spring of this year. With these prices now falling, imports should be an important factor restraining inflation in the near-term future.

It is also important to realize how important imports are to the economy. Non-oil imports came to $3,734 billion at an annualized rate in the second quarter of this year. This is equal to 14.8 percent of GDP. If the prices of items comprising 14.8 percent of GDP are now falling at a 4.7 percent annual rate, instead of rising at a 6.0 percent annual rate, that has to drastically improve the inflation picture. To be clear, we can’t assume that import prices will keep declining, and certainly not at their recent rate, but the inflationary pressure from rapidly rising import prices seems to be behind us. (The import price index prior to the pandemic had a slight downward trend.)

Even this switch from rapidly rising import prices to rapidly falling ones understates the impact on inflation. Shipping costs soared during the pandemic, as we tried to move a vastly increased quantity of goods, even as Covid was forcing shutdowns of ports and forcing many workers to stay home due to illness. One commonly used index increased almost ten-fold at its peak in September of 2021. It has now fallen back almost 70 percent from that peak, and it seems likely it will fall further.

Shipping costs are not included in the import price index. This means that the prices we pay for the goods we are importing are falling even more sharply than is indicated by the import price index. This should go far towards alleviating inflationary pressures.

Productivity

At least implicitly, productivity growth is a huge part of the inflation story. To simplify a bit, inflation will be equal to the rate of wage growth minus the rate of productivity growth. (This assumes profit shares remain constant, among other things.) This means that if we have wage growth of 3.5 percent, and productivity grows at a 1.5 percent annual rate, inflation will be 2.0 percent.

Higher rates of productivity growth mean that we can have more rapid wage growth without higher inflation. I had been noting an uptick in productivity growth through the fourth quarter of 2021, and argued that workplace innovations associated with the pandemic may have put us on a faster productivity growth path.

That hope vanished with the release of the productivity data from the first and second quarter of 2022. They showed annual rates of decline in productivity of 7.4 percent and 4.1 percent, respectively. Productivity data are notoriously erratic, so single quarter surges or declines are best ignored. I have also been skeptical of the drop in GDP reported for the first half of this year, believing that subsequent revisions may show the economy grew during this period.

But that aside, there can be little doubt that productivity growth in the first half of 2022 was terrible. There are two plausible explanations as to why productivity would suddenly decline. One is labor hoarding. The idea here is that companies are finding it difficult to hire and keep workers, so they in effect hire everyone they can and keep them on the payroll whether they need them or not. This is common behavior in a recession, especially with large companies and highly skilled workers.

I am skeptical of this labor hoarding explanation because it typically would be associated with a decline in the length of the average workweek. The idea would be that you keep workers on the payroll, but maybe you have them work 35 hours a week rather than 40, because you don’t need them for 40 hours. You may not need them for 35 hours either, but since you want to keep the worker, it’s necessary to give them something close to normal hours. (Presumably the employer is also paying for health insurance and other benefits.)

Anyhow, there is not much of a case for a big drop in the length of the workweek in the first half of 2022. There had been some decline in the average workweek in 2021. The length peaked at 35.0 hours in January of 2021 and then fell back to 34.8 hours by the fourth quarter. This would be consistent with a story where employers, unable to hire the workers they needed, worked their existing workforce more hours.

There is a somewhat further decline in the first half of 2022, but the average was 34.6 hours, which is still higher than the 34.4 hour average for 2019, before the pandemic. There is a similar story in most major sectors. This doesn’t rule out the possibility of labor hoarding, but it does seem odd that there would not be some decline in the length of the workweek.

The explanation that strikes me as more likely is that supply chain disruptions are proving to be major obstacles to normal production. This story can be best told with the construction sector.

The combined categories in the National Income and Product Accounts of non-residential construction and residential construction (Table 1.1.6, Lines 10 and 13) fell 6.8 percent between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2022. By contrast, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) index of aggregate hours for the construction sector rose 1.0 percent over this period. This would imply roughly a 7.8 percent decline in productivity over this ten-quarter period.[1]

It doesn’t seem plausible that either construction technology or the quality of labor in the industry could have deteriorated so much in such a short period of time. The more obvious explanation for a decline in productivity in construction is that many workers were effectively wasting their time waiting for parts or materials that were needed for them to do their jobs. If there is a comparable picture in many other workplaces, where supply chain issues keep workers from doing their jobs, then the decline in productivity in the first half of 2022 can make some sense.

The positive side of this story is that, if either the labor hoarding or supply chain explanation proves correct, then the drop in productivity reported for the first of 2022 is temporary and should be reversed in future quarters. Data available for the third quarter indicate that we should get some modest positive rate of productivity growth for the quarter.

This brings us back to the costs and inflation picture. The weak productivity performance in the first half of 2022 meant that businesses were seeing sharply higher costs. The data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that unit labor costs rose at annual rates of 12.7 percent and 10.2 percent, in the first and second quarters, respectively. Since the profit share was also above its pre-pandemic level, it seems businesses were having no problem passing on these costs in higher prices, but the data imply that they really were seeing sharply rising costs.

However, with productivity growth returning to a more normal pace, the pressure on costs will be far lower than it was in the first half of 2022. This means that a major source of inflationary pressure will have been removed.

Are We Out of the Woods on Inflation?

As a card-carrying member of Team Transitory, I know that my prognostications on inflation have to be viewed with some serious skepticism at this point, but I would urge people to just look at the data. The story on inflation expectations is clear, investors and consumers both anticipate that inflation will come down to pre-pandemic rates. In addition, wage growth has clearly slowed, not accelerated as the bad story would predict. Whether it has slowed to levels consistent with an acceptable rate of inflation remains to be seen.

Higher import prices had been a major factor pushing inflation higher in 2021 and the first five months of this year. Since May, they have been falling rapidly. The impact of this drop in prices is amplified by a huge reduction in shipping costs over this period. Instead of putting upward pressure on prices, these factors should allow for price declines on many items. (We already see evidence of this on items like appliances, with have been falling in price in recent months.)

Finally, we had a horrible story on productivity in the first half of 2022. The reported decline in productivity during the first two quarters meant enormous increases in costs for businesses, most or all of which seems to have been passed on in prices. The good news here is that we seem to be on at least a normal productivity growth path again in the third quarter. Whether it ends up being faster or slower than the pre-pandemic pace remains to be seen, but at least it will be positive.

For these reasons, we can anticipate that inflation will be much less of a problem in the rest of this year and in 2023 than it has been. Does this story mean the Fed should stop raising rates?

Given the September CPI, it would be difficult for the Fed to declare victory and end its hikes. But it can certainly slow the pace. We all know that the full impact of rate hikes takes time and we are just beginning to see the effect of the most recent hikes. It seems there is much more risk at this point of going too far than going too slow. It is also reasonable for the Fed to at least consider the impact of its hikes on the rest of the world, even though we all understand that it is basing its monetary policy on the needs of the U.S. economy.

A small hike in November can show its determination to restrain inflation, while allowing itself more time to assess the data. If the October employment report shows another month of modest of wage growth, it will provide solid evidence that it has brought wage growth down to a non-inflationary sustainable pace.

Unfortunately, the Fed will not have this report until after its meeting. There seems little risk in going with a smaller hike in November, and then take into account the October employment data, along with other data, in determining its course at future meetings.

[1] This is a very crude productivity measure. On the output side, the residential construction data includes some services related to mortgage issuance, which would not be produced by construction workers. The BLS measure of hours only counts payroll employment, excluding self-employed and likely also many workers who might work off the books.