Article

International Monetary Fund Lifts Veil on Surcharges

Article

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

Since 1997, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has imposed additional fees, called surcharges, on loans to many of its most indebted borrowers. Yet, until very recently, the Fund wasn’t publishing data on surcharges, leaving outside observers in the dark regarding which countries were paying them, and how much they were paying. CEPR and other organizations had to develop their own estimates, and even some countries only discovered late in the game that they were paying these fees. These discoveries have led to increasingly pressing calls for transparency.

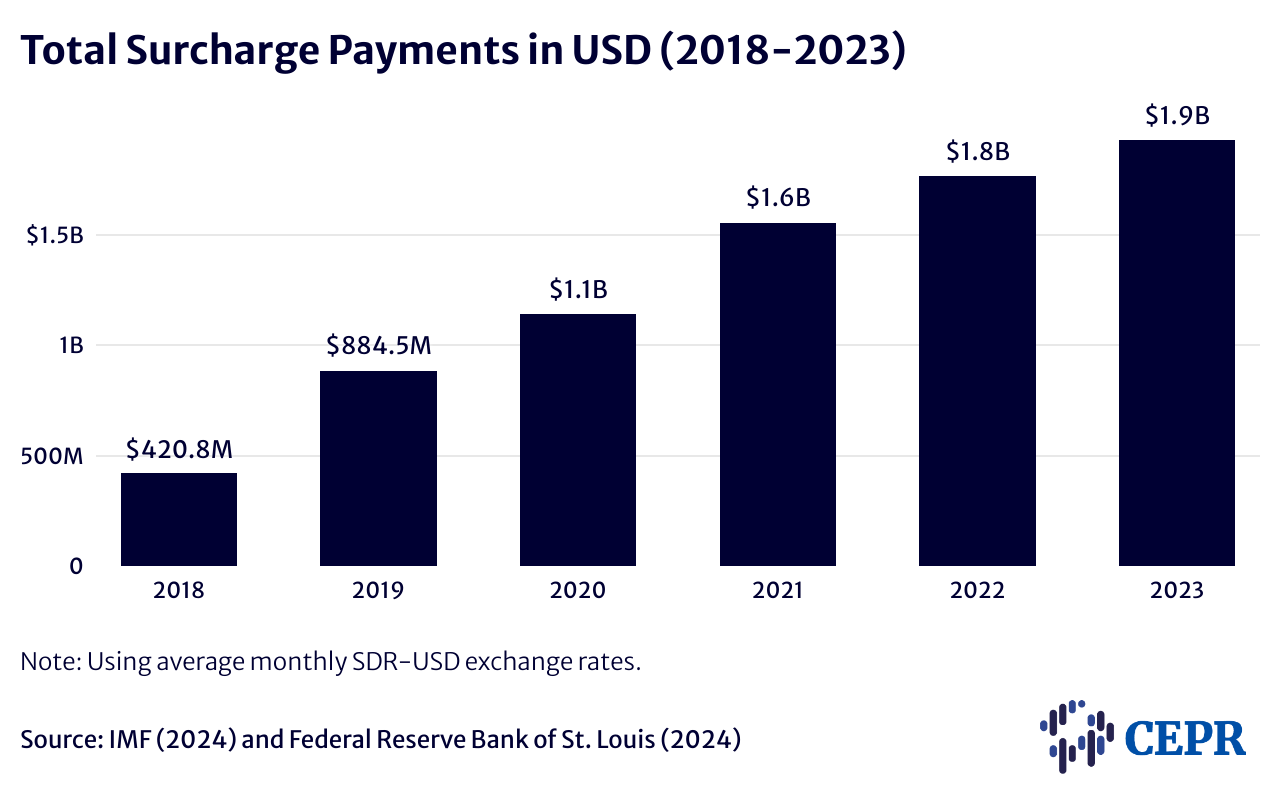

The IMF at last lifted the veil on its surcharge policy by publishing figures through its Financial Data Query Tool in 2023. This newly available data shows that, for affected countries, surcharges amount to 39 percent of conventional General Resource Account (GRA) charges to the IMF, on average, and $7 billion in total, over the past five years. The data also confirms that 22 countries were paying surcharges as of January 2023, up from 8 in 2019.

IMF surcharges are additional payments, on top of regular interest payments and other fees, that countries are required to pay to the Fund if they have high levels of IMF debt or longer term outstanding debt to the Fund. Level-based surcharges are levied if a member country’s outstanding credit to the Fund’s main account, the GRA, exceeds 187.5 percent of their quota, and time-based surcharges are levied on debt in excess of this threshold outstanding for three or more years, depending on the lending facility.

IMF surcharges are additional payments, on top of regular interest payments and other fees, that countries are required to pay to the Fund if they have high levels of IMF debt or longer term outstanding debt to the Fund. Level-based surcharges are levied if a member country’s outstanding credit to the Fund’s main account, the GRA, exceeds 187.5 percent of their quota, and time-based surcharges are levied on debt in excess of this threshold outstanding for three or more years, depending on the lending facility.

Surcharges have been widely criticized for their procyclical nature, effectively punishing countries facing severe liquidity constraints, increasing the risk of debt distress, and diverting scarce resources that could otherwise be used to fund health care, climate action, or other social and development needs. (See “IMF Surcharges: Counterproductive and Unfair” for a more complete discussion of the policy and its consequences.) Further, the Fund has provided no evidence that surcharges accomplish their stated goal of disincentivizing overreliance, and the IMF’s key argument — that surcharges are necessary to support its precautionary balances — is not currently valid.

The IMF’s decision to publish this data is a welcome step toward transparency. However, some opacity remains in projecting surcharge payments for future years. The IMF’s Query Tool appears to only project surcharge payments on existing loans that were effectively disbursed. It does not include surcharge payments derived from commitments — loans under existing arrangements that have yet to be disbursed (also referred to as “prospective credit”). This discrepancy means that the IMF’s Query Tool projections of future surcharge payments are significantly lower than what countries will end up paying.

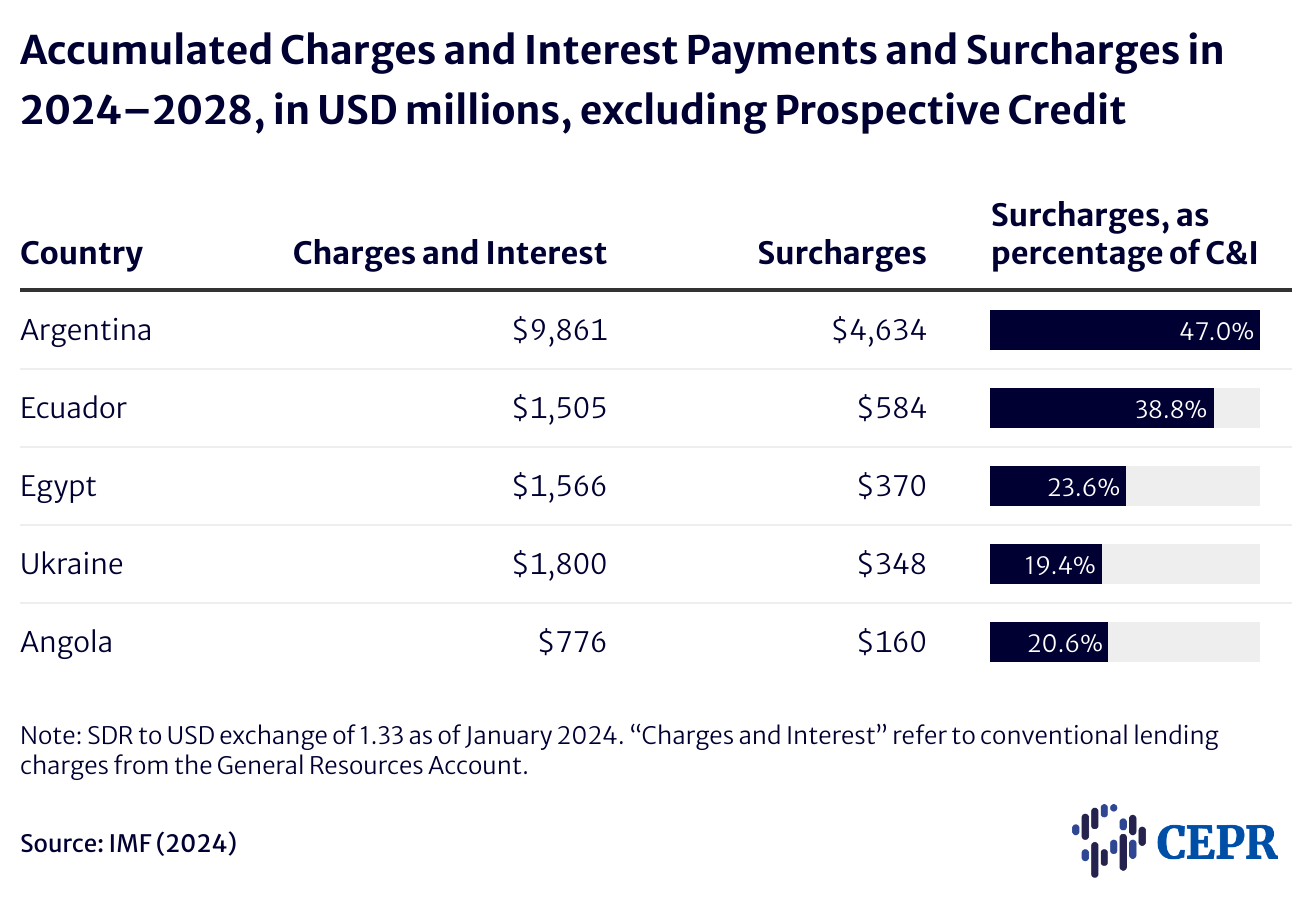

For example, according to the most recent relevant country report, which does project prospective credit, Ukraine is expected to receive more than $10 billion in GRA loans in the next five years. By 2028, the outstanding level of this prospective credit will represent 81 percent of Ukraine’s total outstanding credit. Excluding this prospective credit from projections is likely to greatly underestimate future surcharge payments. If prospective credit is included, we estimate that Ukraine will pay about $1.5 billion in surcharges over the next five years. This is four times higher than the IMF’s projection of $370 million, based solely on existing credit.1

According to the Query Tool, the five countries paying the most in surcharges to the Fund will spend $6.1 billion on surcharges over the next five years, amounting, on average, to 39 percent of their conventional lending charges to the IMF. Again, these figures would likely be significantly higher if surcharges on commitments were included.

As of January 2024, 22 countries are currently subject to surcharges. This is a net increase of six, since CEPR’s most recent estimate from April 2023 — and nearly triple the pre-pandemic number. Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Moldova, North Macedonia, Senegal, and Sri Lanka are now paying surcharges, while Albania is no longer.2 This is roughly 40 percent of all countries making any GRA payments in the next five years — a figure that is difficult to square with surcharges’ purported efficacy as a disincentive.

In recent years, numerous world leaders — including Brazilian president and G20 chair Lula da Silva — the G77, UN officials, UN human rights experts, leading economists, civil society organizations, and more have called for the suspension or complete elimination of the surcharge policy. Given the dominant position of the United States at the Fund, with its effective veto power, the fact that the Fund has thus far failed to heed these calls is likely attributable to the stance of the US Treasury. Members of the US Congress, however, have repeatedly urged reform, and in 2022, the House of Representatives passed legislation directing the US Executive Director at the IMF to support a review and suspension of the policy.

Fortunately, likely due to mounting global calls, there have recently been indications that the IMF, and US Treasury officials, may be willing to consider reviewing the surcharge policy. In September 2023, Under Secretary for International Affairs Jay Shambaugh stated that the Treasury Department is “open to hearing views on surcharge policy reform.” The following month, the chair of the International Monetary and Financial Committee, Nadia Calviño, said the Fund “will consider a review of surcharge policies.”

The IMF’s own data supports widespread concerns that the surcharge policy presents a tremendous burden on heavily indebted countries. Furthermore, the net increase of six surcharge-paying countries in less than a year, and the significant growth in total surcharge payments, indicate that this burden is only growing. These payments are unnecessary for the IMF to maintain its precautionary balances well above target levels.

As the 2024 IMF Spring Meetings, scheduled for April 19–21, approach, the evidence is clearer than ever that the Biden administration should use its voice and vote to end the Fund’s surcharge policy.

Stay tuned for an upcoming deep-dive based on the IMF data release and CEPR’s new estimates for future years, which will include surcharges on outstanding credit as well as commitments in existing arrangements.