Article

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

There is a battle in Washington policy circles over whether the story of inequality is one of the 30 percent of the workforce with college degrees pulling away from those with less education, or a small group at the top pulling away from everyone else. The Hamilton Project recently published a paper that seemed to support the former story, noting that college grads did much better than those without college degrees between 1990 and 2013.

However, the Hamilton Project story doesn’t quite fit. College grads have not been pulling ahead in the new century. The wages of workers with only college degrees have also been stagnating since 2000.

The problem with this type of analysis is that it misleads readers into thinking that a large group of well-educated Americans have benefited from the rise in inequality. In reality, the “winners” from increased inequality are really a much smaller group of incredibly rich Americans, not a large group of well-educated, upper-middle-class workers.

But the Hamilton Project hasn’t been the greatest offender on this front. That honor undoubtedly goes to New York Times columnist David Brooks, who has been misleading readers on this point for years.

In 2014, Brooks wrote that the problem “[a]t the top end” of the income distribution is “the growing wealth of the top 5 percent of workers.” Two years earlier, in a column titled “The Great Divorce,” Brooks wrote:

“Democrats claim America is threatened by the financial elite, who hog society’s resources. But that’s a distraction. The real social gap is between the top 20 percent and the lower 30 percent. The liberal members of the upper tribe latch onto this top 1 percent narrative because it excuses them from the central role they themselves are playing in driving inequality and unfairness.”

This is not what the data show. Economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty have pulled data on tax returns from 1913 to 2013 to examine the changing distribution of pre-tax income within the U.S. Their findings should convince everyone that Occupy Wall Street had it right: the growth of income inequality really is all about “the 1 percent.”

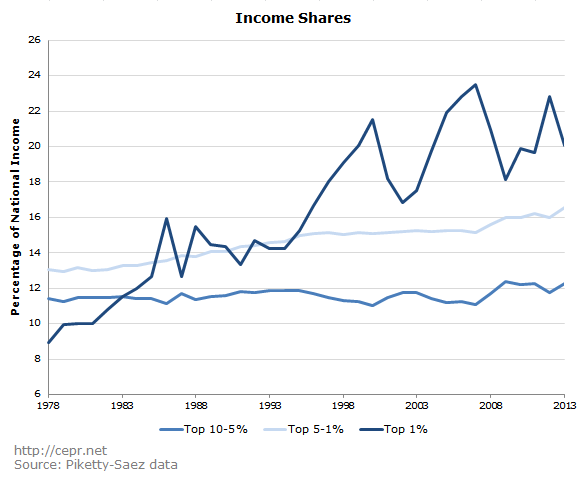

The Piketty-Saez data allows users to break down the shares of income going to the top 10 to 5 percent, the top 5 to 1 percent, and the top 1 percent of income earners. Including capital gains, the shares of national income going to the three aforementioned groups can be broken out as follows:

So this isn’t really a story of the top 20 percent or even the top 5 percent of income earners breaking away from everyone else. The share of national income going to those in the top 10 to 5 percent of the income distribution rose from 11.45 percent in 1978 to 12.27 percent in 2013, an increase of just 0.82 percentage points; the share going to the top 5 to 1 percent rose from 13.09 percent in 1978 to 16.55 percent in 2013, an increase of 3.46 percentage points. By comparison, the share going to the top 1 percent rose from 8.95 percent to 20.08 percent, an increase of 11.13 percentage points. While the share of national income going to the top 5 to 1 percent has increased by about a quarter, the share going to the top 1 percent has more than doubled.

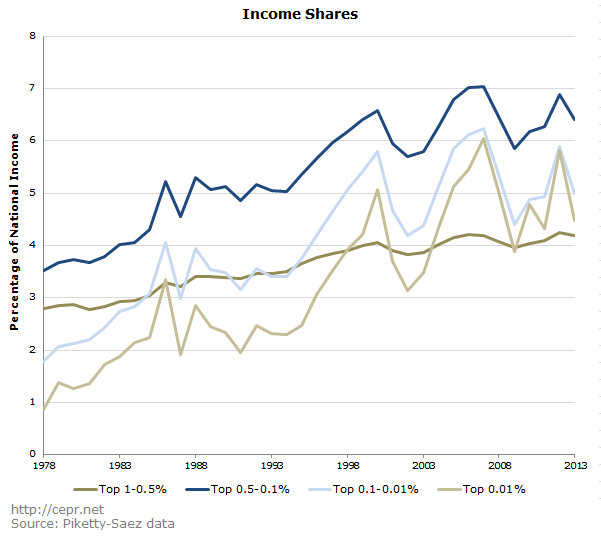

This is true even if we look within the top 1 percent. By breaking down the income shares of the top 1 to 0.5 percent, the top 0.5 to 0.1 percent, the top 0.1 to 0.01 percent, and the top 0.01 percent of income earners, we can see that the uber-elite are pulling away from the rest of the elite:

Those within the top 1 to 0.1 percent of the income distribution saw their shares of national income less than double between 1978 and 2013; the income share of the top 0.1 to 0.01 percent nearly tripled; and the share going to the top 0.01 percent increased more than five-fold.

So when Brooks writes that we need to worry about the top 5 percent or the top 20 percent, he’s misguiding his readers. But even when he has written about the top 1 percent, his claims have been misleading. Less than two months ago, Brooks wrote:

“It is true that wages for college grads have been flat this century, and that is troubling. But this is not true of people with post-college degrees, who are doing nicely. Moreover, as Lawrence Katz of Harvard points out, the argument that college doesn’t pay is partly a product of a short-time horizon. Since 2000, the real incomes of the top 1 percent have declined slightly.”

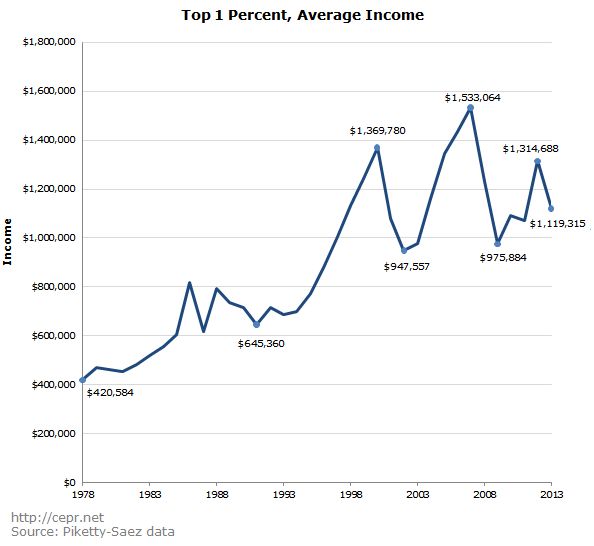

The claim that real incomes for the top 1 percent have declined slightly is technically true, yet still highly misleading. The graph below shows the average real incomes (in 2012 dollars) of members of the top 1 percent between 1978 and 2013, again using the Piketty-Saez data. I’ve labeled the levels of income achieved at specific peaks and troughs, as well as my start and end dates. (The specific years labeled are 1978, 1991, 2000, 2002, 2007, 2009, 2012, and 2013.)

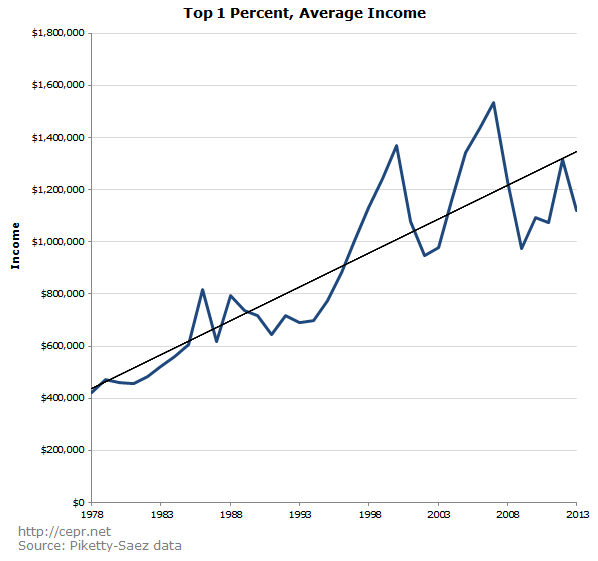

So Brooks picked out a single year in which the incomes of the top 1 percent had clearly experienced a temporary bump due to the stock bubble, then used this point to argue that “the real incomes of the top 1 percent have declined slightly.” Anybody taking an honest look at the numbers can tell that the incomes of the top 1 percent have been trending upward. To make this point even more clearly, here’s the same graph with a trendline fitted to the data:

The R-squared value for the trendline is 0.7604; this implies that the trendline fits the data quite strongly. Clearly the real incomes of the top 1 percent are rising rather than falling.

So the rise of inequality has created a large number of “losers” and very few “winners.” When you talk about who’s benefiting from inequality, it’s really not about a large group of well-educated workers. It’s all about the 1 percent.