Article

Private Equity in Healthcare: Profits before Patients and Workers

Article

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

This was originally published in the magazine – Labor and Employment Relations Association (LERA), Perspectives on Work.

On March 25, 2021, U.S Representative Bill Pascrell, Jr. (D-NJ-09), Chairman of the House Ways and Means subcommittee on Oversight, held hearings into the growing power of Wall Street firms in the healthcare industry. The hearings focused on recent research documenting higher than average death rates in private equity (PE) owned nursing homes. A rigorous study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), found that mortality rates in PE-owned nursing homes were 10 percent higher than the overall average, while Medicare billing was 11 percent higher. PE-owned homes shifted resources away from patients. Frontline nurses spent fewer hours with patients, and to compensate for lower staffing, the homes made 50 percent higher use of antipsychotic drugs (drugs associated with higher mortality rates). They also spent more money on things unrelated to patient care, such as monitoring fees.

Patient care suffers because the PE business model represents an extreme form of the ‘shareholder value model.’ In a recent scathing op ed, Congressman Pascrell wrote, “Private equity influence stretches like an octopus, with tentacles in large and small hospitals, physician practices, dental practices and scores of nursing homes … Private equity firms follow a well-worn blueprint: buying companies, saddling them with mountains of debt and then squeezing their acquisitions like oranges for every dollar before tossing the rind into the wastebasket.”

PE firms promise their investors ‘outsized returns,’ but how can they produce these high returns in an industry fraught with thin or negative operating margins and declining government reimbursement rates? They answer is, they can’t — without resorting to tactics that allow them to extract wealth from providers in the short run and to exit the company before disaster hits. PE firms held healthcare investments for less than five years in the period 2012-2019, according to industry data.

Notably, PE firms have financial expertise, not healthcare expertise, and they are not bound by the Hippocratic Oath like doctors and other healthcare professionals. They use high levels of debt to buy the company (which multiplies their returns); but the debt is loaded on the company they acquire, immediately undermining its financial stability. And if something goes wrong, the PE firm can walk away. In a recent study, for example, researchers found that PE owned companies across all industries had a 20 percent bankruptcy rate versus only 2% for comparable publicly-held companies. This translates into fewer hospital beds, layoffs of workers, or loss of workers’ pension benefits. PE firms also make money by cutting costs – of labor and supplies – leading to understaffing and unsanitary conditions that both undermine patient care and workers’ jobs and working conditions — as in the nursing home study and the Steward Healthcare case below (see box).

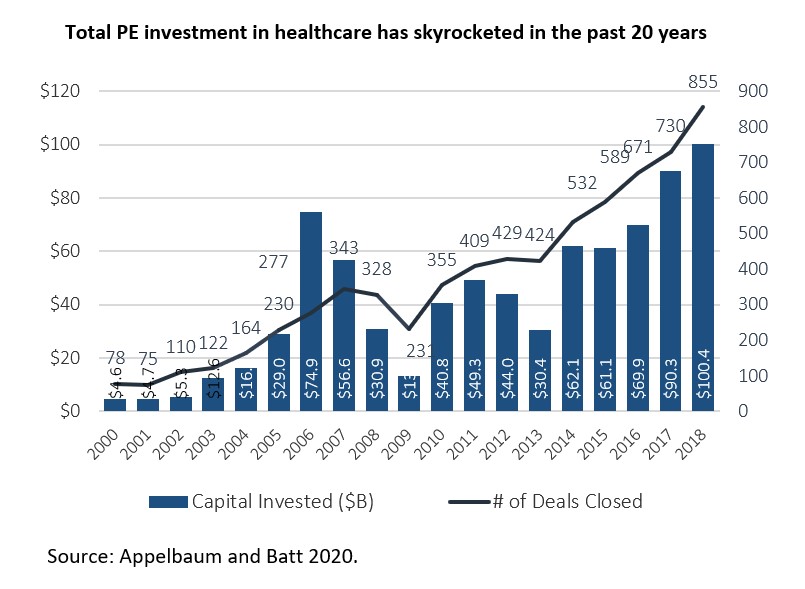

PE firms find healthcare attractive in part because third party payers insure a steady cash flow to service the debt. Their investments and power have skyrocketed in the last two decades, with total investments rising from $5 billion in 2000 to over $100 billion in 2018 — an historic high in that year and a 20-fold increase overall. The cumulative total for the period was 7,300 ‘deals’ worth $833 billion.

As PE firms promise their investors ‘outsized returns,’ they need to maximize revenues – hence, ‘outsized bills.’ Surprise medical billing has become a serious problem for people who need to seek emergency room (ER) or other hospital services — even for those who think they are covered by their insurance policies. The hidden actors are leading private equity firms. Since 2013, two private equity owned companies have cornered at least 30 percent of the market for outsourced ER staffing: Envision Health owned by KKR and TeamHealth owned by Blackstone. Together they employ over 90,000 healthcare professionals nationwide. A recent study by Yale health economists found that when EmCare (Envision’s ER staffing arm) took over emergency departments, it nearly doubled its charges for patient care compared to the charges billed by previous physician groups. They found that TeamHealth uses the threat of sending high out-of-network surprise bills for ER doctors’ services to an insurance company’s covered patients to gain high fees from the company as in-network doctors.

Why has this happened? In recent years, financially-squeezed hospitals have increasingly cut costs by ‘outsourcing’ their ER and other critical services to doctors or physician staffing firms that are not covered by the insurance contracts that the hospital has negotiated. When this happens, patients may receive unexpected and unreasonably high medical bills because the ‘out-of-network’ doctors are free to charge whatever they want. When hospitals started outsourcing, PE firms were quick to jump into the market — buying up small physician practices and combining them into national staffing firms with considerable market power. In 2019 alone, PE firms spent at least $54 million lobbying against Congressional legislation that would curb surprise medical bills. A bill prohibiting surprise billing finally passed in December 2020 and will go into effect January 1, 2022. Surprise bills to patients are banned. But disputes between medical providers and insurance companies will be subject to arbitration, which is likely to result in payments to PE-owned staffing companies beyond in-network rates. The bill does require arbitrators to begin negotiations using the average in-network price, not what PE–owned staffing companies charge. This is expected to substantially hold down payments to these companies.

Surprise medical bills also characterize air ambulance services; and PE firms KKR and American Securities own two of the three largest providers—Global Medical Response and Air Methods. As small town and rural hospitals have closed at disproportionately high rates in the last decade, patients must travel long distances to access hospital or emergency care. If emergencies hit – a heart attack, a car accident — they have little choice but to take an air ambulance to get care as quickly as possible. The most authoritative study to date, published by the Brookings Institutions, found that, “… two private equity firms, who together make up 64% of the Medicare market, had a standardized average charge of $48,250 (7.2 times what Medicare would have paid) … markedly higher than the $28,800 (4.3 times what Medicare would have paid) standardized average charge for the same service by air ambulance carriers ….” Air ambulance companies are also covered by the legislation banning surprise bills to patients. Surprisingly, ground ambulances are not covered by the ban on surprise bills.

PE firms also can make money by maximizing revenue generation through unnecessary treatment add-ons and over-testing. In some cases, this has led to higher billing charges to Medicare and Medicaid (as the nursing homes did); and in others, it has led to fraudulent billing or ‘false claims’ for government reimbursements that are illegal — as evidenced in a 2021 investigative report by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project — “Money for Nothing.” Taxpayers end up paying the costs.

In addition, as illustrated in the Steward healthcare[1] and Prospect Medical cases below, PE firms extract wealth by splitting their companies into a ‘property’ company and an ‘operations’ company, selling off the property, and using the sale proceeds to pay themselves and their investors large dividends. The operating companies – in this case hospitals – are saddled with long leases and (typically inflated) rent payments on property they once owned. This translates into financial instability or lack of resources for improving care for patients and training and upgrading workers.

|

Steward Healthcare System: Selling off Property to pay Investor Dividends at Patients’ Expense PE firm Cerberus Capital bought out a small Catholic hospital system in the Boston area, Caritas Christi Health Care in 2010. It was required to comply with the Attorney General’s rules to invest in the hospital in exchange for converting it to a for-profit system. But when the rules expired after 5 years, Cerberus immediately sold off most of its hospitals’ property for $1.25 billion — leaving the hospitals saddled with long-term inflated leases. It used the sale proceeds to pay itself almost $500 million in dividends, and then used the Steward system as a platform for a massive debt driven acquisition strategy – buying out 27 hospitals in 9 states in 3 years between 2016 and 2019. The rapid, scattershot M&A strategy was designed to create a large corporation that could be sold off in five years for financial gain — not for regional healthcare integration. Its debt load exploded, and by 2019, its financials were deeply in the red. Its Massachusetts hospitals were the worst financial performers of any system in the state and had higher than average rates of patient falls, hospital acquired infections, and patient readmissions, according to Massachusetts state data. Cerberus exited Steward in 2020 in a deal that left its physicians, the new owners, holding the massive debt. |

Moreover, some PE buyouts of hospitals appear to be ‘pure real estate plays,’ as in the case of Hahnemann Hospital in Philadelphia. It was run into the ground by an investor-owned for-profit chain (Tenet), which sold it in 2018 to PE firm (Paladin) and a Chicago real estate PE firm. By June, 2019, the PE firms filed for Hahnemann’s bankruptcy and by September, closed the hospital.

Notably, they separated out and retained ownership of the hospital’s valuable real estate, which was excluded from the bankruptcy. Public and city officials viewed the deal as a PE strategy to take over valuable city center real estate – nearly six acres and the largest contiguous space in the city — and sell it off for expensive condos and office buildings. The property went up for sale in July, 2020, one building sold for almost $10 million, and the rest has remained vacant as of April, 2021 [2].

Private equity firms have continued their rapacious behavior even during the COVID-19 pandemic when healthcare organizations have struggled to provide care to millions. Returning to the Hahnemann case, in March, 2020, city officials tried to negotiate use of the hospital for Covid-19 patients during the Pandemic, but the owner’s offer was almost $1 million per month in rent for the 500 beds – something the city couldn’t afford.

That same month, Pennsylvania’s governor got hit from behind by another PE firm –Cerberus Capital, owner of the Steward system. Cerberus had acquired a small hospital in Easton, PA in a leveraged buyout in 2015; and as with its other hospitals, undermined its financial stability by immediately selling off its property (which the hospital had owned since its founding in 1890) and pocketing the money. When the coronavirus pandemic hit in March, 2020, Cerberus immediately contacted the PA governor and demanded $8 million per month from the federal bailout fund to keep Easton Hospital open – or else it would close the hospital and 694 employees would lose their jobs. Facing the COVID crisis, the governor secured the money and paid it — until the hospital could be sold to another nearby hospital, which guaranteed is financial security.

“Dividend recapitalizations’ are another form of extracting money that has continued during the pandemic. This is a fancy term for loading a portfolio company with additional debt, which is used to pay dividends to the PE firm and investors – another tactic that depletes resources that should go to improving patient care, staffing levels, and working conditions. A 2021 investigative report by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project identified 15 recent examples of these dividends taken by PE owned healthcare companies, some during the pandemic. Most of these providers are not known ‘brands’, but rather small providers across all segments of healthcare: Trident USA (providing mobile diagnostic services to nursing homes), Sterigenics (a medical sterilization company) Aspen Dental, Home Care Assistance, Millennium Health (medical testing), Multiplan (medical billing), Pharmaceutical Product Development, PT Solutions (physical therapy provider), and more.

Taxpayer capitalism

The U.S. Department of Justice is investigating PE firm’s illegal use of CARES Act aid. Three PE backed hospital companies owned by Apollo, Cerberus, and Leonard Green have received $2.5 billion in COVID-19 funds. Blackstone and Ares Management also have received millions while loading more debt on their providers to pay themselves dividends.

Blackstone is one of the worst PE repeat offenders. It saddled its ventilator rental company (Apria) with over $400 million in new debt so it could pay itself and its investors $460 million in dividends in the last 3 years – over ½ of this in 2020. Simultaneously, it cut needed respiratory staff and submitted millions in false claims to the government. Apria settled the law suit for $40.5 million.

“The company, the complaint says, offered huge bonuses to salespeople who signed up many new patients to use the ventilators, while employees who did not meet the targets were at risk of losing their jobs. The government alleges that employees combed through patient records to find people who were using cheaper oxygen devices so that salespeople could try to upgrade them to the more lucrative ventilators. Salespeople pushed physicians to order their patients the more expensive devices, declining to tell them that cheaper machines could be configured to meet the same needs, the complaint alleges.” (WAPO)

Some PE firms combine all of these financial tactics to extract wealth from healthcare providers – and Prospect Medical Holdings, owned by PE firm Leonard Green, is a particularly egregious case. They have flaunted state regulators while extracting dividend recapitalizations and simultaneously taking COVID-19 federal bailouts.

|

Prospect Medical Holdings: Stripping Assets from Safety Net Hospitals while Taking Federal Covid-19 Bailouts In 2010, Leonard Green acquired five community health systems, renamed them Prospect Medical Holdings, and expanded the system through debt-financed M&As to 20 hospitals and 165 clinics by 2019. The hospital system’s debt level multiplied, its quality ratings fell to among the lowest in the country, its unfunded pension liabilities rose substantially, and its operating margin crashed from a healthy 10.8 percent in 2015 to 0.6 percent in 2018. It sold off much of its hospitals’ real estate so that hospitals now pay inflated rent; and it closed 5 hospitals in Texas, laying off 1,000 workers. In the meantime, it extracted at least $658 million in fees and dividend recapitalizations. And taxpayers pay: 55 percent of Prospect’s annual net revenue comes from Medicare and Medicaid, and it received $375 million in COVID-19 federal rescue aid in 2020. |

PE firms are subject to scant regulatory oversight, operating with virtually no transparency – which brings us back to the importance of Representative Parcell’s recent oversight hearings. Parcell introduced a bill in April, 2021 to close a tax loophole that allows PE firms to be taxed at the capital gains rather than regular income rate. But that is only the beginning. In 2019, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) introduced the ‘Stop Wall Street Looting Act,’ specifically targeting a range of practices that allow PE firms to be treated as ‘passive investors,’ rather than the owners and employers who make all of the strategic decisions for a company. Warren’s bill would dramatically increase transparency by requiring disclosure of fees, returns, and political expenditures; ban dividends in the first two years a private equity firm owns a portfolio company; prioritize worker pay and pensions in the event of bankruptcy; hold PE firms liable under the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act; treat PE returns as regular income; and hold firms responsible for debt and legal obligations incurred at portfolio companies under their ownership, among other things.[3] Given the immense problems facing the country in the Covid era, this bill may not be taken up in Biden’s first year, but there is growing anger over private equity’s pillaging of Main Street companies, even among Wall Street financiers and evidenced in Wall Street Journal exposes. The time is ripe for Congressional action to curb wealth extraction from our healthcare system.

[1] La France, Aimee, Rosemary Batt, and Eileen Appelbaum. 2021. “Hospital Ownership and Financial Stability: A Matched Case Comparison of a Non-Profit Health System and a Private Equity Owned Health System.” Forthcoming in Jennifer Hefner and Ingrid Nembhard, eds., The Contributions of Health Care Management to Grand Health Care Challenges. In Volume 20, Advances in Health Care Management. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing.

[2] D’Mello, Kevin. 2020. “Hahnemann’s Closure as a Lesson in Private Equity Healthcare.” J. Hosp. Med. (May), 15(5):318-320.; “Philadelphia Hospital to Stay Closed After Owner Requests Nearly $1 Million a Month,” NYT. March 27, 2020; “Brandywine buys 1920s building on former Hahnemann hospital campus.” Philadelphia Inquirer. January 26, 2021.

[3] Warren, Baldwin, Brown, Pocan, Jayapal, Colleagues Unveil Bold Legislation to Fundamentally Reform the Private Equity Industry. July 18, 2019. https://www.warren.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/warren-baldwin-brown-pocan-jayapal-colleagues-unveil-bold-legislation-to-fundamentally-reform-the-private-equity-industry; Adam Lewis. 2021. “Private equity could face a reckoning as power shifts in Congress.” January 21.