Article • Expose the Heist: Power and Policy in Unprecedented Times

Trump’s Idea to ‘Free Up Our Forests’ Will Threaten Public Lands

Article • Expose the Heist: Power and Policy in Unprecedented Times

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

At the beginning of March, Donald Trump signed an executive order requesting the Bureau of Land Management and the US Forest Service to issue guidance on boosting timber production. The order mirrors administration officials’ perspective that public lands are “assets” that can be used to generate more revenue – or, as Elon Musk recently put it, “I think logically we should privatize anything that can reasonably be privatized.”

The order was under the guise of forest management, claiming increased logging would decrease wildfire risk and preserve fish and wildlife habitats. However, the order allows agencies to bypass environmental regulations such as the Endangered Species Act, which is not exactly conducive to sustainable timber production or protecting habitats. Really, the move is a shot at Canada, which recently applied 25 percent tariffs to lumber exports.

To be clear, using Forest Service resources to harvest timber isn’t new. The Forest Service’s timber harvesting activities are part of a vegetation management program that also includes prescribed burns and planting new trees. Tree removal, which usually occurs through natural processes such as fire, maintains forest health by eliminating invasive species, diseased vegetation, and ladder fuels that lead to hotter, higher wildfires. But, like with any process, there’s a balance.

Historically, boosting timber production has had some extremely negative environmental impacts. The California Gold Rush, which lasted from 1848 to 1855, led to the decimation of the forests of the Sierra Nevadas as towns and large cities like San Francisco and Sacramento needed more lumber to support growing populations. As demand for housing decreased, so did logging operations. Because the Forest Service had a policy that lasted over 100 years requiring all fires to be extinguished immediately, the forests grew back thick and full of potential fuel. The slash – debris in the form of branches, leaves, and wooden stems that remain after logging – was left over time to fuel future fires.

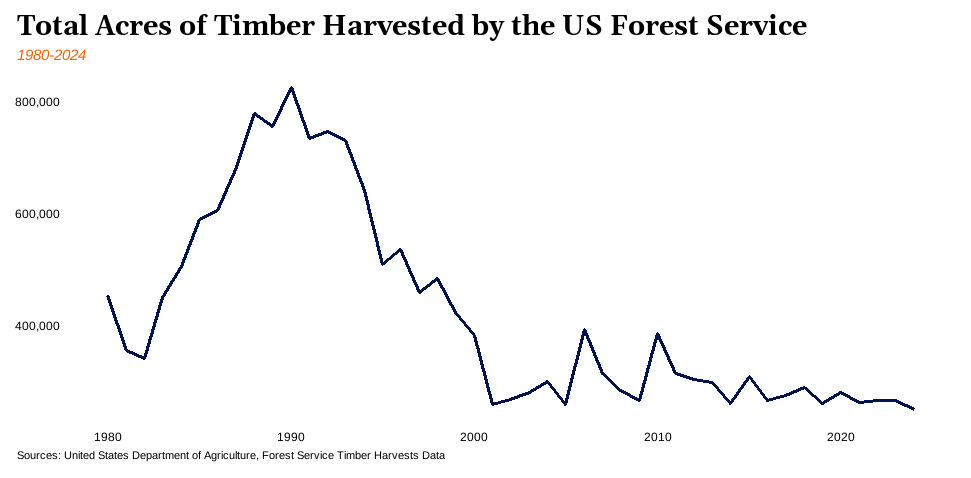

Even if policymakers want to ignore lessons from the 1800s, they could learn from warning signs as recently as the 1980s. After the 1980 and 1981-82 recessions ended, commercial and housing construction ramped up. Logging on federal lands, particularly old-growth forests, surged to unprecedented levels as the demand for timber rose (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

In 1990, the northern spotted owl, an indicator species for the health of the old-growth forests, was listed under the Endangered Species Act, which led to a federal judge halting logging activities in those areas. Indicator species are animals, plants, birds, or bugs whose presence reflects the conditions of a particular ecosystem. That last fact is key because while many were quick to blame an owl for the subsequent loss of jobs and timber production (though that job loss was much smaller than the industry led the public to believe), the more significant issue was what the owl’s absence indicated. The old-growth forest ecosystem was collapsing. Not just timber production but life itself would be unsustainable in such a rapidly changing environment. This is what making America great again looks like for the Trump Administration, which in 2020 had eliminated protections for protected habitats across Washington, California and Oregon.

Instead of clear-cutting land, the government could invest more money in the Forest Service and reinstate recently laid-off employees. Investing in forest management can result in more sustainable timber harvesting practices and would actually decrease wildfire risk and preserve fish and wildlife habitats as promised. This work is vital because our national parks and forests are indeed assets. The United States set these areas aside because it believed they should be protected from harm and saved for the enjoyment and discovery of future generations. This is an issue with broad support in the US, with environmentalists joining hunters and fishers in criticizing declining resources for forest management. Trump’s proposed actions will only rob the American people of that in the name of short-term capital accumulation and a US-Canadian trade war.