Issue Brief

Stop Wall Street Looting Act: More Necessary Now Than Ever

Issue Brief

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

Today, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) reintroduced the Stop Wall Street Looting Act, legislation that would curb some of the worst excesses of the private equity industry.

Eileen Appelbaum, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) and co-author of the book “Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street,” released a letter to Senator Warren that traces the rise of this dangerous industry. The letter explains the economic circumstances that fueled private equity’s explosive growth, and the risky financial schemes that have delivered massive profits to investors while decimating American health care companies – doing lasting damage to the interests of workers, caregivers and patients.

The letter also takes a close look at the looting of Steward Health Care, the Massachusetts-based health care chain that was driven into bankruptcy.

As Appelbaum’s letter states, “The Stop Wall Street Looting Act contains many provisions to bring the looting of economically viable companies by Wall Street owners to an end, and to protect the interests of workers in the bankruptcy proceedings…. Financial market regulators need far more transparency about the financial situation of private investment funds and the opaque interactions among them in order to safeguard US financial markets from unexpected disruptions or worse.”

Read the full letter below.

Dear Senator Warren,

I am writing regarding the reintroduction of the Stop Wall Street Looting Act (SWSLA). This legislation will help shed light on the risky strategies being pursued by private equity companies and help put an end to the looting of viable companies by Wall Street investors. Private equity owners have done considerable harm, particularly in the health care industry – putting patients and workers at risk for the sake of profits.

It’s important to understand some of the recent history of private equity. For more than a decade following the financial crisis of 2007-2009, interest rates were low. Beginning in September 2007 and continuing through 2008, the Federal Reserve (the Fed) aggressively cut interest rates. This was a boon to private equity (PE) firms, which sponsor investment funds and recruit investors to provide private capital to acquire companies for the funds’ portfolios. Debt – lots of it – is used to finance these purchases, with the acquired company responsible for repaying the debt.

In this low-interest rate environment, so-called leveraged buyouts proliferated and were a profitable strategy for the PE firms. The total number of private equity leveraged buyouts increased from 2,272 in 2008 to 4,957 in 2019 and peaked at 7,521 in 2021 (after the Fed cut already low interest rates to address the economic challenges of the pandemic), before falling back to 6,106 in 2022. Total deal value nearly tripled from $247 billion in 2008 to $701 billion in 2019, before peaking at $1.12 trillion in 2021 and falling back to $819 billion in 2022.1

While there are approximately 5,000 private equity firms in the US that own or provide financial backing for 18,000 firms employing 12 million workers,2 leveraged buyouts are still the bread and butter of the business. Private equity makes money in a leveraged buyout by loading the acquired companies (its portfolio companies) with debt and stripping them of resources – from monetizing real estate through sale-lease back arrangements with a Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT), requiring them to take on more debt to pay dividends to the PE firm and its investors (a dividend recapitalization), and by collecting fees for monitoring the portfolio companies (largely money for nothing). Looting a company of its resources deprives it of the ability to use those resources to invest in itself and its workers. Even in exuberant times in financial markets, the combination of a high debt burden and these financial engineering strategies too often lead to financial distress for a company unable to pay its rent or make payments on its debt. In a worst-case scenario, financial engineering may drive a PE-owned company into bankruptcy.

The bankruptcy of Steward Health, a hospital chain serving small towns and cities in Eastern Massachusetts, illustrates how the private equity owner and executives, working with the Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) that propped it up, were able to enrich themselves while driving the hospital system into bankruptcy – failing the patients, workers and communities that depended on them. We focus on Cerberus’ and Steward’s involvement with Medical Properties Trust, the REIT that enabled much of the bad behavior that led to Steward’s demise, because so little is known about REITs by the public and policymakers.

Private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management formed Steward Health Care in 2010 when it acquired Caritas Christi, the largest community-based health care system in New England with six hospitals employing 10,000 workers and serving more than half a million patients annually. Cerberus acquired the hospitals and affiliated units in a $420 million leveraged buyout plus assumed debt and pension liabilities of $475 million that valued the healthcare system at $895 million.3 Steward quickly added-on five more acute care community hospitals; by 2012, Steward was a $1.8 billion company, with 17,000 employees (making it the third largest employer in Massachusetts), caring for 1.2 million patients annually.4

Because Cerberus was converting the nonprofit Caritas Christi into a for-profit system, the Massachusetts Attorney General required that certain conditions be met, including that Cerberus invest $400 million in upgrading the hospitals’ infrastructure. Cerberus funded the system’s infrastructure expenditures and the acquisition of additional hospitals by monetizing some of Steward’s assets via sale-leaseback deals, and by having the health care system load up on junk bonds and other debt. In its 2015 report, the AG noted, “The solvency position of the system declined as debt increased, while operating losses and pension fund charges eroded equity.”5 Nonetheless, Cerberus had met the stipulations for investment in infrastructure and was released from AG oversight thereafter.

By 2016, Cerberus had sold off most of its hospitals’ property for $1.25 billion to Medical Properties Trust (MPT), which took a 5 percent equity stake in Steward. The hospitals assumed the long-term costs of inflated leases, substantially reducing their net revenues. Cerberus used the sale proceeds to pay itself and its investors almost $500 million in dividends, pay down debt, and launch a massive debt-driven acquisition – buying out 27 hospitals in 9 states in three years between 2016 and 2019. MPT was a critical partner in all these deals, entering into sale-lease-back arrangements, which substantially funded the additional buyouts while leaving the acquired hospitals with long term leases that substantially curtailed net revenues.

The first acquisition was of eight hospitals in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Florida, purchased for $311.9 million from the failing CHS system.7 Steward immediately sold off the hospitals’ real estate to Medical Properties Trust for $301.3 million, which means that MPT essentially financed the eight-hospital purchase and implies that the hospitals’ operations were only worth $10.6 million to MPT and its investors.8

In 2017, Cerberus moved on to strike a deal with PE firm TPG to buy IASIS Healthcare, a chain of 18 hospitals strewn across Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana. MPT was pivotal in TPG’s sale of the IASIS hospitals to Steward for $2 billion. MPT and IASIS entered into a sale-leaseback and mortgage financing arrangement amounting to $1.5 billion in total.9 MPT also paid $710 million to acquire the real estate of nine hospitals and provided a $700 million mortgage loan on two other hospitals. MPT then invested $100 million in Steward, bringing MPT’s ownership of Steward to 9.9 percent.10

With the IASIS deal, Cerberus almost doubled the size of the Steward system, but also absorbed a system loaded with debt by the previous PE owners. Steward represented 37 percent of MPT’s portfolio. In 2018, Medical Properties Trust leased additional properties to Steward and acquired five others, leading MPT to own a total of $4.052 billion worth of Steward-related real estate as of December 31, 2019.11

But Steward’s Massachusetts hospitals were in deep financial trouble. They were the worst financial performers of any system in the state, with the highest level of debt and higher-than-average rates of patient falls, hospital acquired infections, and patient readmissions.12 Steward had an equity financing ratio of negative 37.6 percent in the fiscal year 2018,13 which indicated how highly leveraged and financially unstable Steward had become. S&P Global Ratings also gave MPT a negative outlook because of its increased exposure to Steward, which represented 36.6% of the REIT’s revenues at the time.14 Steward could not direct funding and resources to stabilize hospital finances or to improve the quality of care without increasing the chance that it would default on its debt.

Despite these problems, MPT was ready to help Cerberus exit the Steward system in 2020. Having more than recouped its investments, Cerberus turned to a novel strategy that depended on MPT financing. In May 2020, Cerberus transferred ownership to a group of Steward’s doctors, led by its CEO Ralph de la Torre, in exchange for a note due in five years that paid regular interest to Cerberus and that could be converted back to equity – ensuring that Cerberus would gain whether the system did well or not.15 If Steward were to head to bankruptcy, Cerberus would do better as a bondholder than a stockholder— as equity is wiped out.

In January 2021, Steward borrowed $335 million from Medical Properties Trust to pay off the Cerberus’ note — making MPT Steward’s largest creditor, its landlord, and a minority owner of the hospital system as well. In May 2021, Cerberus exited Steward completely.16 Only a month later, Steward went on to buy out another five hospitals in Florida for $1.1 billion. As part of the deal, MPT acquired the real estate underneath the hospitals for $900 million.

As these details confirm, MPT has partnered fully with Steward, its largest tenant, in the acquisition of hospitals for the Steward chain. This has made MPT one of the largest owners of US hospital real estate. MPT, a publicly traded company, has been able to attract investors because of its rapid growth, due disproportionately to its partnership with Steward and the long-term leases it has with health systems that provide essential services. A REIT is similar to a mutual fund in that it allows ordinary people to invest in real estate. They are marketed as safe investments that own diversified properties. And, like mutual funds, their investors can cash out and exit the REIT. Medicare provides a steady stream of payments to hospitals that make them attractive investments. The rent payments, scheduled to rise steadily over the length of the lease, promise an unending stream of lucrative dividends. However, should Steward, MPT’s largest tenant, falter financially, the effects on MPT could be disastrous. Steward depends on MPT to finance its expansion, and MPT relies on rental income from the Steward system to retain its investors and protect its share price. This intertwined relationship between MPT and Steward has raised questions and come under scrutiny.

Despite assurances from MPT to its investors in 2019 that Steward’s profits were strong, the health system constantly lost money. Steward lost about $207 million in 2017 and about $271 million in 2018. The pandemic wreaked havoc on Steward’s finances, as it did on most hospitals. Despite receiving more than $441 million in government funds to address problems created by COVID-19, Steward had a net loss of $408 million that year. With Steward on track for its largest loss ever in 2020, there were concerns that the hospital system would not be able to meet its 2020 rental payment of $385 million to MPT. Steward’s finances improved dramatically as a result of two transactions. In the summer 2020, Steward executives, acting in their personal capacity, formed a joint venture (JV) with MPT. MPT loaned $200 million to the JV, which used the $200 million to buy Steward’s international assets, booking a $173 million cash gain for Steward that enabled it to pay its rent.17 MPT is essentially providing funds to Stewart to pay its rent and hiding from its investors the risks that this arrangement entails. From 2016 to 2021, Steward paid MPT roughly $1.2 billion in rent and mortgage interest; MPT’s CEO drew $16.9 million in total compensation.18

In 2022, MPT sold 50 percent of the real estate of eight Steward hospitals in Massachusetts to Macquarie Asset Management. Apollo Global Management and its affiliated companies – including life insurer Athene that managed the annuity savings of people – provided Steward with a $920 million loan. This gave Apollo a stake in Steward that could prove profitable if the hospital chain entered bankruptcy, since creditors play a big role in how a bankruptcy plays out.19 In the next two years, Steward’s finances deteriorated further: In 2023 Steward was behind in its rent on the Massachusetts hospitals by $110 million, and by 2024 it had stopped paying what it owed to its vendors, medical equipment suppliers, employees, staffing firms and others.

In May 2024, Steward Health Care declared bankruptcy. At the time of the bankruptcy, Steward operated 31 hospitals in 10 states, employed almost 30,000 workers, and cared for more than two million patients a year.20 Steward’s $9 billion in liabilities were exposed in the bankruptcy proceedings. Steward owed $6.6 billion to MPT on its long-term leases, $1.2 billion on its various loans, almost $1 billion to vendors and suppliers, and nearly $290 million to workers and staffing firms in unpaid compensation.21

In the 12 months preceding Steward’s bankruptcy in May 2024, hospital executives and CEO Ralph de la Torre paid themselves unseemly high salaries as the company was spiraling. The hospital chain failed to pay its vendors and suppliers, sometimes leading to unspeakable tragedy. But its top leaders lined their pockets with money that could have safeguarded patient health and safety. Ralph de la Torre’s gross salary for the period May 2023 to April 2024 was $3.8 million. In that same period, 14 top executives received gross compensation of at least $1 million each, including bonus payments.22

Enrichment schemes began much earlier. In 2020, when MPT provided a $335 million loan to Steward’s new physician owners to pay off the loan from Cerberus, de la Torre was a recipient. Around the time of Cerberus’ exit, Steward paid a $111 million dividend to these physicians, including de la Torre. Shortly after, de la Torre bought himself a $40 million dollar yacht. Steward lavished gifts on its executives, including two private jets and a suite at the AA Arena in Dallas.23

In 2022, the Boston Globe reported that Steward purchased a multimillion-dollar apartment in Madrid for de la Torre. The hospital system also paid for his trips on the company’s corporate jets to vacation destinations where it had no hospitals and no obvious business connections. Sometimes de la Torre put money in his own pocket by arranging for Steward to contract for services with companies in which he had a financial interest. In February 2022, when Steward’s financial situation was already dire, de la Torre donated $10 million to a private school for a STEM center. But some of that money came not from his family foundation as he claimed; it came from Steward. To make matters worse, de la Torre was part owner of the business that oversaw construction of the center. Unlike the unsavory dealings of Cerberus and MPT, which are legal, de la Torre’s questionable actions may have broken bankruptcy laws and corporate laws. A grand jury in Boston is reportedly investigating the matter.24

While Cerberus, MPT and de la Torre were making off with Steward’s resources, the hospital system was understaffed, its infrastructure was deteriorating, it lacked necessary supplies and was unable to care for patients or provide for the safety of its workers. State data show that Steward reduced staff over a period of two years prior to declaring bankruptcy. Chronic understaffing increased the workload of nurses, doctors and other staff, making it impossible for even the most dedicated professionals to give all patients the care they required. Patients lined emergency department hallways because of a lack of ICU nurses, a nurse caring for a patient requiring one-to-one nursing care might have eight patients in their care. Understaffing of registration desks made that process stressful for nurses and dangerous for patients, several of whom collapsed while waiting their turn. Patients suffered from delays in getting their medicines and necessary treatments. These conditions created dangerous conditions for patients and intolerably stressful and demoralizing work situations for clinical staff and frontline workers.

Employee complaints filed with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health detail declining investment in facilities, broken equipment, and dysfunctional administration. For nurses and other employees, the lack of supplies and equipment compromised their ability to care for patients appropriately. The shortages ranged from standard items like baby formula or food for a hungry diabetic, to common medical supplies like IV tubing or bandages to functioning hospital beds and life-saving equipment. Nurses often went out to buy basic necessities for patients, including boxes appropriate for returning the remains of an infant that had died. Vendors that had not been paid in months stopped delivering supplies or showed up at Steward hospitals to repossess their equipment – leaving employees to improvise to provide care for patients. Basic infrastructure repairs went undone. According to a nurse at St. Elizabeth’s hospital in Brighton, there were supposed to be six elevators but only one was in working order – and it did not always work. She worked on the 10th floor of the hospital and described being given a sled to drag patients down 10 flights of steps in an emergency. It is abundantly clear that working conditions deteriorated at Steward hospitals along with patient care.25

Steward Health Care made large payouts to investors while not paying its vendors and suppliers, thus endangering the health and safety of patients. Department of Public Health officials found Good Samaritan Medical Center in Brockton was low on the supplies needed to treat trauma patients, even though it is the only trauma center in that region. They found that St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton had run out of certain mechanical heart valves because it had not paid the supplier. Steward is also behind on payments for MRI and CT machines.26

For some patients, staffing and equipment problems had tragic consequences. From 2019 to 2024, at least 15 patients died, and 16 others were injured. Sick patients collapsed and one patient died waiting in line to register at Good Samaritan Medical Center because the hospital was understaffed, when fewer than half of the nurses that should have been there were present. A new mother died the day after giving birth at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, after developing a deep bleed that could have been stopped with an embolization coil. The hospital’s coils had been repossessed a few weeks earlier by the company that supplied them because Steward had not paid for them.27 In addition, federal regulators found that at least 2,000 patients were put in immediate danger at Steward hospitals.28

Hospital closures in Massachusetts, Texas, Arizona, Louisiana, Arkansas, Pennsylvania, and Ohio have reduced access to care for patients and resulted in the layoffs of about 3,900 workers.29 Patients have fewer hospitals to serve them, and it takes longer to reach a hospital in an emergency or to give birth.30 This too is a reduction in patient care quality.

Everything that Cerberus – the hospitals’ private equity owner – and Medical Properties Trust – the REIT that owned the hospitals’ real estate – did was legal. That’s why passage of the Stop Wall Street Looting Act is so important.

The Stop Wall Street Looting Act contains many provisions to bring the looting of economically viable companies by Wall Street owners to an end, and to protect the interests of workers in the bankruptcy proceedings. To end the looting of companies, SWSLA will hold private investment funds jointly liable with their portfolio companies for repayment of debt, for informing employees in advance of mass layoffs or plant closings (WARN Act), and for any settlements related to violations of labor laws or other laws. It will impose a 100 percent tax on income from monitoring fees collected from portfolio companies and impose a limit on the deductibility of business interest. It will put guard rails around taxpayer-financed capitalism by requiring public disclosure of the amount of public funds received and how they were spent. A company that receives public funds could not use them to acquire another company or pay dividends to its owners for four years, and SWSLA would also prevent capital distributions in excess of 10 percent of the target firm’s total debt in a given year. In view of the role that inflated rents paid to real estate investment trusts (REITs) following sale-leaseback transactions play in the bankruptcies of hospitals, nursing homes and other health care entities, SWSLA prohibits payments from federal health care programs to providers that sell assets to REITs. SWSLA also prevents employers from permanently replacing striking workers, clarifies unfair labor practices, and streamlines the bargaining process – strengthening the ability of unions to act as a countervailing force to unbridled corporate greed.

SWSLA would also protect each workers’ wages and benefits – up to $20,000 for wages and $20,000 for benefits – in the event that the company ends up in bankruptcy. Currently, workers’ claims are last and often do not get paid, while administrative services of the bankruptcy lawyers are paid first. SWSLA would move up the priority for payments owed to workers to administrative expenses. Then wages, severance, and payments owed to workers’ health and welfare plans and to pension plans would get paid first. It also places limits on the compensation of top executives and managers, and on golden parachutes for them as they leave the bankrupt company.

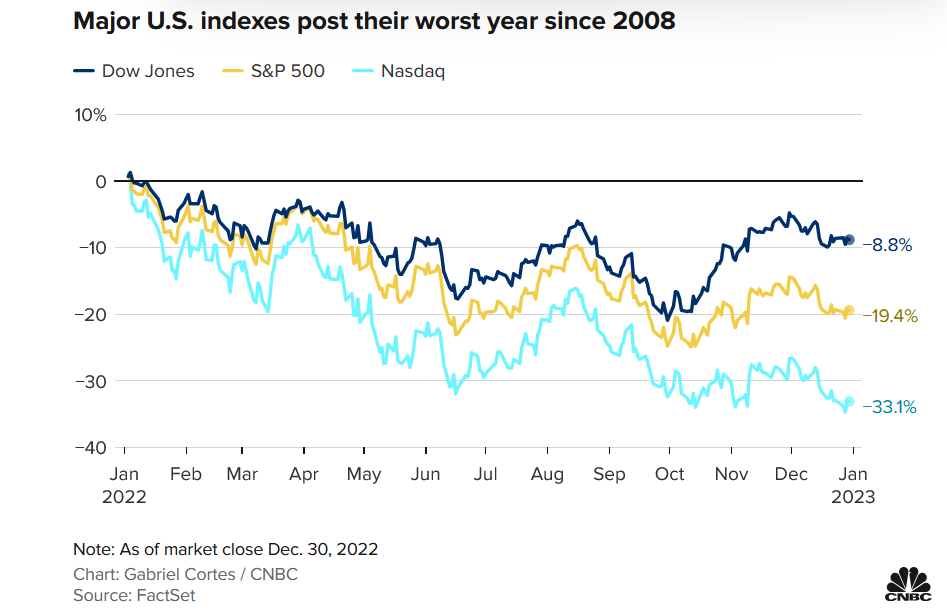

The easy money era came to an end in 2022. Higher-for-longer inflation led the Fed to aggressively raise interest rates, with six increases between October 2022 and July 2023.31 The Federal Funds rate rose from 3.25 percent in October 2022 to 5.5 percent in July 2023, where it remained until September 2024.32 As a result, the stock market tanked between January and December 2022, with the S&P 500 falling almost 20 percent and the Nasdaq declining by a third (see the figure below). Public equities recovered relatively quickly. The S&P 500 ended 2023 up 24.2 percent.33

The end of the era of easy money and the increase in interest rates was a shock to private investment funds, compounded by the dramatic decline in 2022 in stock markets. The result has been a hiatus in PE activity including buyouts, exits and fundraising. Higher interest rates increased financing costs, making it more difficult for investment funds to undertake leveraged buyouts. Many portfolio companies experienced financial difficulties and saw their credit scores marked down by Moody’s or other rating agencies. Bankruptcies surged; there were 104 bankruptcy filings by private investment fund portfolio companies in 2023, a record number and up 174 percent over 2022. And this is an undercount, since the analysis is limited to private companies with some public debt, and it excludes companies whose debt was provided by private credit funds. By comparison, bankruptcies overall for US companies were up 73 percent over the prior year. Healthcare accounted for the largest number of portfolio company bankruptcies with 34. Akumin, a radiology and oncology company, and Air Methods, a medical ambulance company, were among the largest in the healthcare sector.34

Private equity firms face persistent difficulties beyond high interest rates and challenging financing markets. Unlike companies that trade on a stock market whose values quickly adjust to market conditions and are available for everyone to see, the value of unsold companies in private equity funds are guesstimates made by the PE firm, usually on a quarterly rather than a daily basis. PE firms that were happy to raise the value of their portfolio companies when the value of publicly traded companies rose were reluctant to do the same when public markets dropped dramatically. Divergent views of the value of companies held in PE portfolios – with buyers thinking these assets were overvalued – made it difficult to exit these investments.35 Deal value fell to $1.3 trillion in 2023, down from $1.7 trillion in 2022 and $2.2 trillion in 2021. Returning companies to the public markets via an initial public offering (IPO) would reveal what the market thought the company was worth, and likely result in a downgrade of the value of every company in that fund’s portfolio. Sales to strategic buyers as well as to other PE funds fell precipitously as buyers and sellers could not agree on price. Sellers saw unsold assets pile up in PE portfolios while buyers, unable to find attractive deals, held record levels of ‘dry powder’ (available funds that have not yet been spent). Slow deal making left private equity funds with $2.59 trillion in dry powder globally in 2023.36 Exits fell 25 percent in 2023 compared with 2022. The inability to exit had follow-on effects for PE investors: Fundraising fell off as investors did not get the cash returns they were accustomed to receiving, and were reluctant to commit additional capital to private equity. Additionally, the lack of cash payouts meant PE investors had less to plough back into PE. Public equity firms were under pressure from their investors to return cash.37

Private equity firms responded with heightened use of more extreme financial engineering strategies. Among the risky strategies PE firms are using to provide short-term returns to their investors are subscription line loans, net asset value loans, and continuation funds. All three result in cash to the PE funds that they can use to satisfy investors’ demands for cash payouts. In subscription line loans, the PE fund borrows against the commitments its investors have made to the fund. This piles leverage on leverage and reduces the ultimate returns to pension funds and other investors as the loans and interest are paid out of the fund’s earnings. Net asset value (NAV) loans are loans against the combined asset value of all the companies in a fund’s portfolio. While the companies held by a fund are treated as separate entities – so a failure of one does not affect the rest of fund’s assets – NAV loans undercut this protection for investors, making all of the portfolio companies in a fund liable for repaying the loan if one of them should fail. Finally, continuation funds allow a PE fund to move one or more portfolio companies out of an existing fund into a new one. Existing investors in the original fund can cash out or move their investment to the continuation fund. New investors can participate in the continuation fund. The PE firm makes money on the transaction, collecting carried interest as the old fund closes out.

Another strategy pursued by PE funds are private credit funds, which are intended to raise longer-term returns. They enrich PE partners and investors but increase the risks to the retirement savings of millions of Americans and pose a potential danger to the US financial system.

In 2013, banking regulators – the Fed, the FDIC and the Comptroller of the Currency – issued joint guidance to banks warning against the dangers of burdening a company with debt in excess of six times earnings (EBIDTA), as debt above that level substantially increased the risk of financial distress and bankruptcy. This briefly put a crimp in private equity’s ability to do leveraged buyouts. But private equity soon answered this challenge by setting up private credit and direct lending funds to finance buyouts and lend to portfolio companies as well as other corporations.38

S&P Global ratings estimates that private credit is an almost $1.4 trillion business today. Just seven PE firms – KKR, Blackstone, Apollo Global Management, The Carlyle Group, Ares Management, TPG and Blue Owl – spent $121 billion in the second quarter of 2024 on private credit strategies.

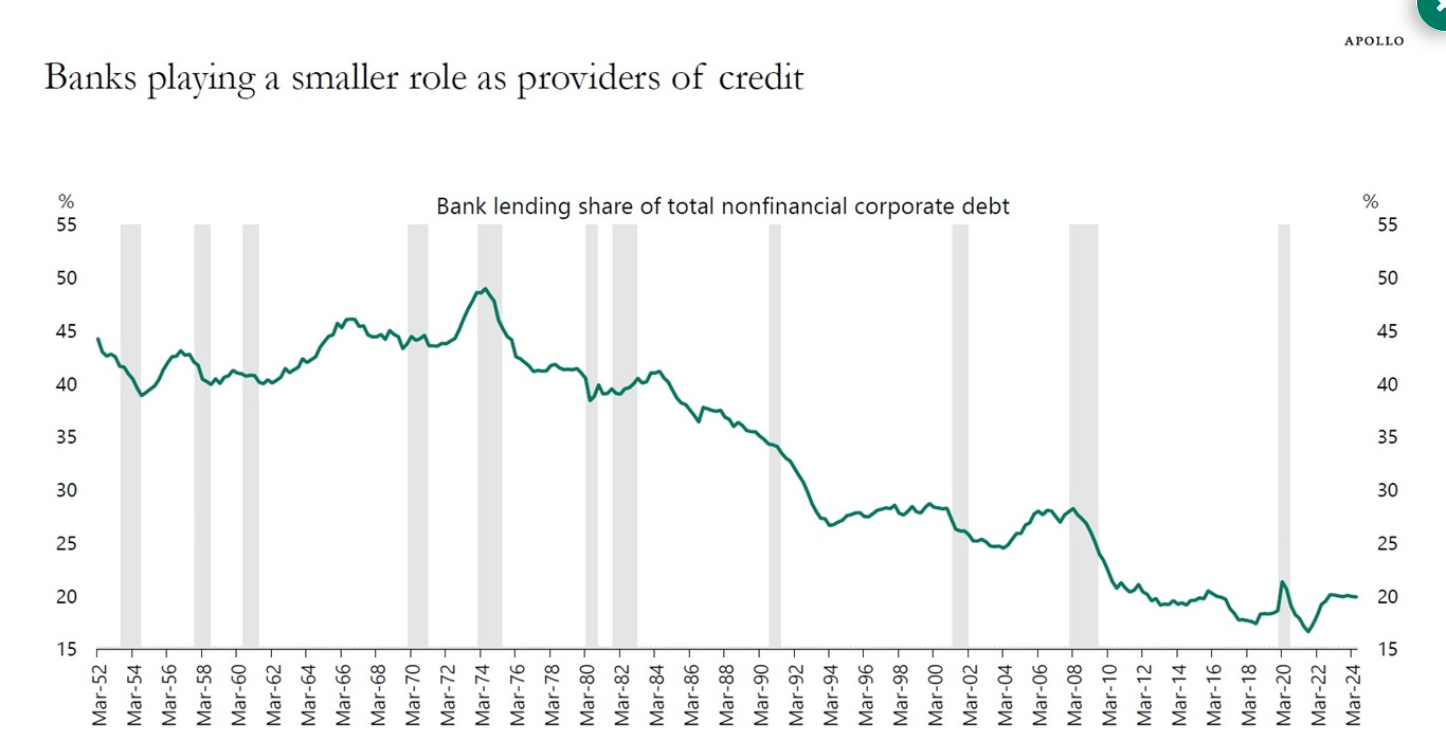

The growth of private credit funds as a source of capital for leveraged buyouts is, in part, a reaction to the retreat of banks which are subject to regulations designed to protect the safety and integrity of the US financial system.

Another important reason for the growth of private credit is that private equity is gobbling up life insurance companies in order to get access to their annuity businesses and the huge volume of assets these companies manage. Now in control of these assets – which constitute the retirement savings of millions of people seeking a safe investment for their old age – PE funds are putting them into riskier investments in mortgage-backed and other asset-based securities and collecting high fees for doing so. Essentially, PE is moving the annuity savings from plain vanilla securities such as government and corporate bonds to asset-based securities offered by credit funds. Not surprisingly, Apollo – which owns life insurance and annuity provider Athene – was responsible for $52 billion of the $121 billion deployed in private credit in Q2 of this year.39

Private credit funds have enabled PE firms to circumvent the stricter regulation of the banking system. These funds do not make even the most basic disclosures about what their operations or financials look like. It’s not possible to judge whether they are financially stable or may collapse if the economy slows.

Banking regulations were designed to avoid a repeat of the disastrous disruption of markets during the financial crisis. Working around them may enrich PE moguls, but at the cost of increasing the riskiness of the US financial system.

The Stop Wall Street Looting Act was never more important than it is today. Financial market regulators need far more transparency about the financial situation of private investment funds and the opaque interactions among them in order to safeguard US financial markets from unexpected disruptions or worse.

Sincerely,

Eileen Appelbaum