Article

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

Last week the Associated Press reported, “Out of every $100 of U.S. contracts now paid out to rebuild Haiti, Haitian firms have successfully won $1.60”. The AP focused on two of the largest contractors with USAID, Chemonics and DAI, two companies we had previously reported on. The AP article cites a USAID Inspector General (IG) report that showed that both Chemonics and DAI were hiring significantly fewer Haitians in the Cash-for-Work programs than what was originally thought. A closer look at the Inspector General report (PDF) finds that this was only one of many problems with these two companies.

First, it is important to highlight the distinction between Chemonics, DAI and other contractors providing Cash-for-Work (CFW) services. There are a total of four contractors who are providing CFW programs in Haiti, two of them through USAID/Haiti and two through USAID’s Office of Transition Initiatives (OTI). While USAID’s website describes their role as the primary U.S. agency to “extend assistance to countries recovering from disaster, trying to escape poverty, and engaging in democratic reforms,” the Office of Transition Initiatives has a more overtly political aspect. OTI describes itself as supporting “U.S. foreign policy objectives by helping local partners advance peace and democracy in priority countries in crisis. Seizing critical windows of opportunity, OTI works on the ground to provide fast, flexible, short-term assistance targeted at key political transition and stabilization needs.” USAID documents, examined by Haiti Grassroots Watch, also betray a political motive behind the CFW programs: they “decrease chances of unrest.” In this way, they may have a similar function as past USAID/OTI programs such as OTI sponsorship of soccer games during the 2004-2006 post-coup regime that OTI saw as undermining support for Fanmi Lavalas and protests against the undemocratic government (and, we would add, the rampant human rights abuses it was perpetrating).

According to the USAID IG report, while the contractors under USAID/Haiti were relatively more successful, the OTI contractors (Chemonics and DAI) had numerous problems. Both DAI and Chemonics operate under an Indefinite Quantity Contract with USAID/OTI that allows them to bypass the traditional bidding process and begin operations on the ground quickly when an opportunity for engagement arises.

The Indefinite Quantity Contract with Chemonics provides some insight into the role that OTI plays in US foreign policy and in regards to foreign disaster assistance. The contract specifies the four “criteria for engagement”:

· Is the country important to U.S. national interests?

· Is there a window of opportunity?

· Can OTI’s involvement significantly increase the chances of success?

· Is the operating environment sufficiently stable?

The contract continues, going into more detail on each criterion. Under the first criterion, the contract states “OTI seeks to focus its resources where they will have the greatest impact on U.S. diplomatic and security interests.” When assessing if there is a “window of opportunity”, the contract states that “OTI cannot create a transition or impose democracy, but it can identify and support key individuals and groups who are committed to peaceful, participatory reform. In short, OTI acts as a catalyst for change where there is sufficient indigenous political will.”

These ominous words should raise the eyebrows of anyone unfamiliar with OTI, an interventionist arm of USAID that has been used in democracies such as Venezuela (2002-present), and Bolivia (2004-2007). The U.S. government’s desire to promote “transition” in such democratic countries has aroused considerable controversy, and understandably: the above language frames OTI’s activities in terms of something short of a coup d’etat or other government destabilization (a “create[d] transition” or “impose[d] democracy”). This raises questions also regarding why the U.S. government feels an OTI presence is called for in Haiti.

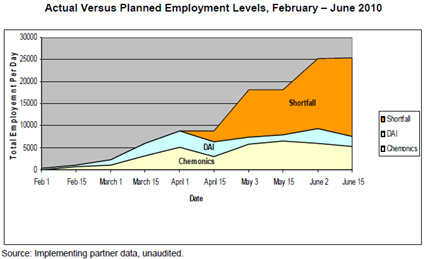

Turning back to the Inspector General’s report, although the AP article does note that Chemonics and DAI were spending roughly 70 percent of their expenses on equipment and materials, it does not say what the original projections were. DAI and Chemonics both planned to spend just 30 percent on material and equipment, compared to 70 percent on personnel. As the AP noted, this resulted in just 8,000 Haitians being hired per day, compared to 25,000 originally planned. The shortfall is easy to spot in this graph, from the IG report:

The number of jobs was not the only area in which the IG found deficiencies. Although the report found that DAI “generally complied” with safety procedures, it found Chemonics lacking:

At Chemonics’ CFW sites, Chemonics allowed workers to participate in rubble removal even if hard hats, gloves, goggles, and boots were not available for distribution. In some cases, site supervisors did not enforce the requirement that workers wear the protective equipment while on duty. Some workers at the sites visited complained that the boots did not fit properly. Therefore, not only did some workers never receive boots, but also other workers who did receive boots could not wear them. Unlike DAI, Chemonics had not established procedures for monitoring or enforcing the use of protective equipment at job sites.

The report also found that community involvement in the selection of workers could have been strengthened. Rather:

Chemonics could allow local mayors to select the workers, while DAI could allow mayors to select team leaders, who would then select individual workers. Both approaches limit the transparency of the selection process and increase the risk of corruption or favoritism by granting decision-making authority to a few individuals.

Although the contractors agreed to stop these practices by end of October 2010, before the elections, it is worrisome that these contractors could have used these Cash-for-Work programs to help incumbent politicians in the November election. However both Chemonics and DAI defended the policy because, “their program guidance is consistent with their goal of community stabilization by strengthening support for the Government of Haiti and local governments.”

The IG report also suggested greater transparency in the selection of sites for rubble removal. Since it is quite expensive to remove rubble from private lots, the IG noted that “corrupt individuals might seek to use CFW efforts for personal gain.” Because of this, “project officials stated that the clearing of private houses could be justified only in rare situations”. Yet the IG found that:

Despite this guidance, the audit team observed workers removing rubble from the lots of private residences next to two of the four Chemonics rubble removal sites visited during the audit. Chemonics officials later confirmed that it was clearing the residential lots in conjunction with a road renovation project. USAID program officials confirmed that there are no formal procedures for selecting private homes for clearance, that private homes do not meet USAID/OTI’s site selection criteria, and that the implementing partner had not notified USAID/OTI of the exceptions.

Perhaps most telling, these contractors operated with little to no oversight. The IG report found that while USAID/Haiti had undertaken financial reviews of their implementing partners, USAID/OTI had not. The report states that, “Although DAI and Chemonics were also expending millions of dollars rapidly on CFW programs in a high-risk environment, USAID/OTI had not yet performed these internal control reviews.”

These findings are important for many reasons. Given the track record of these contractors, their failure to live up to their contracts in Haiti should come as no surprise and should force USAID to reconsider the millions of dollars they give to them. USAID should also shift away from politicized projects and put the interests of the people they are ostensibly trying to help first.