October 20, 2021

Video

Thank you, Senator Warren, Ranking Member Kennedy, and distinguished Members of the Subcommittee. I am pleased to be here today, at this important hearing, to discuss how the Stop Wall Street Looting Act will rein in excesses and end abuses by private equity firms, keep American companies strong, and protect the economic vitality of communities.

By way of background, I am currently the Co-Director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Prior to joining CEPR, I held academic positions as Distinguished Professor of Labor Studies and Employment Relations in the School of Management and Labor Relations at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, and as Professor of Economics at Temple University. I earned a PhD in economics at the University of Pennsylvania.

My co-authored book with Cornell University Professor Rosemary Batt, “Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street,” is a balanced account of private equity that was selected by the Academy of Management – the premier professional association of business school faculty – as one of the four best books published in 2014 and 2015. The book was a finalist in 2016 for the prestigious George R. Terry Book Award.

More recently, Professor Batt and I have studied the role of private equity in health care. Our publication, “Private Equity Buyouts in Health Care – Who Wins, Who Loses.” examines the private equity business model in health care. It focuses, among other topics, PE’s acquisitions of physician practices and its growing role in the collection of medical debt – so-called revenue cycle management.

Private Equity, Largely Unregulated, Plays a Growing Role in the U.S. Economy

By net asset value, global private equity assets under management have grown ten-fold since 2000. In 2020, global assets under management by private equity firms reached $4.5 trillion – and growing. There are about 5,000 private equity firms worldwide. More than half of assets under management are held by U.S. PE firms.

About 8,000 companies in the U.S. are currently owned by or have financial backing from private equity firms. The cumulative number would be far larger. According to the website of the American Investment Council (AIC), the U.S. PE lobbying arm, employment in the private equity industry and private equity-backed companies combined numbers more than 11.7 million U.S. workers. In the year 2019, AIC reports that PE firms in the U.S. invested $700 billion in 4,841 businesses (latest year).

The industry is a sizable and growing financial player in the U.S. economy. Yet, it is largely unregulated. It is famous for loading companies with excessive amounts of debt, for selling off the real estate of companies it acquires, for its lack of transparency about fees it collects or the performance of the companies it owns, and fiercely protective of tax loopholes that allow PE partners to line their pockets with billions that should have gone to the Treasury. Private equity provides a newly acquired company with a game plan for its first 100 days and the metrics it is expected to meet. It selects the company’s board members and freely fires its CEO if he doesn’t get with the program. The Stop Wall Street Looting Act will establish guardrails that rein in behavior that undermines the viability of companies it owns to the detriment of workers, vendors, suppliers, creditors and the communities where they are located.

The PE industry claims that it provides access to financing and to expertise on organizational improvements – upgrading accounting and IT systems, improving the company’s digital and social media presence – and advising on business strategy. This is often the case when smaller PE firms buy out small to mid-sized companies for its portfolio and provides this support. The PE firm ‘turns these companies around’ and sells them at a profit. Small and mid-sized companies have relatively few assets to be used as collateral for loans, so the amount of debt loaded on them is not excessive. By the same token, they have relatively few assets that could be stripped, and their cash flow will not support further borrowing in the junk bond market to pay their PE owners dividends. In this case, the PE firm relies on operational improvements to create value for the company and the economy in order to achieve a successful exit at a price much higher than it paid to acquire the company, often via a sale to a strategic buyer who sees value in the company’s products or services.

Most private equity deals, by deal count, fall into this category and PE firms are able to provide small and mid-sized portfolio companies with operational and strategic improvements. The Stop Wall Street Looting Act will have little effect on the operations of these PE firms.

However, most of the capital committed to private equity by pension funds, endowments, sovereign wealth funds and other institutional investors flows to PE firms that sponsor large PE funds. Mega funds – those with capital commitments of $5 billion or more – used to be rare. Now they are becoming increasingly common. Mature, successful companies with predictable cash flow make attractive acquisition targets for the portfolios of large funds. But the companies provide few, if any, opportunities for organizational or strategic improvements. They do, however, present many opportunities for the PE firm to make money for itself and its investors through financial engineering – that is, by using the assets of the company as collateral for the high levels of debt loaded onto it to finance its acquisition by the PE fund; restructuring the organization not for a productive purposes but to reduce the taxes it pays; using the revenue it generates to have the company take out junk bond loans in order to pay dividends to its PE owners; charging its portfolio companies monitoring and transaction fees that go straight to the coffers of the PE firm; and stripping the company of valuable assets and using the sale proceeds to line the pockets of the PE investors. The Stop Wall Street Looting Act will end the most extreme and abusive of these practices.

PE firms are playing with other people’s money – capital committed by PE investors to the PE fund it sponsors and the loans advanced to it by creditors as it loads debt on the companies it acquires. Keeping up with payments on the debt often means the company must squeeze its workforce, cutting pay and benefits and even laying off workers. If despite these efforts, the company faces financial distress, it is the creditors who will lose money and, in extreme but not uncommon cases, force the liquidation of the company in order to recover as much of the money they lent as possible.

A veil of secrecy hides much of what private equity firms do, the fees and expenses they charge to their investors for managing their money, or the monitoring fees and transaction costs they charge to their portfolio companies. In particular, there is virtually no information about the financial condition or performance of portfolio companies available to the public or even to the PE investors that own the companies. Private equity is famously ‘private,’ requiring non-disclosure agreements and preventing even the investors in its funds from speaking to each other about the deal they cut with the PE firm.

The Stop Wall Street Looting Act will establish guard rails that will protect the interests of investors in PE funds and the creditors that provide the financing for leveraged buyouts. It will not mandate the level of debt that can be levered on portfolio companies, but it will discourage the excessive use of debt by holding the decision-making General Partner of the PE fund and the private equity firm jointly responsible with the portfolio company for repaying the debt in case of financial distress. It will tear back the veil of secrecy that surrounds the actions of private equity and hides the financial health of portfolio companies from public view. We – and the PE firm’s investors and creditors – have to take the word of the PE firms for the value of companies in their portfolios.

The PE industry promotes the myth that if PE firms are making money, they must be creating value for the companies they own, the companies’ investors and creditors, and for the economy. In my testimony today, I want to address that myth by describing how large PE firms can make money without creating value and even when they destroy it.

Leveraged Buyout Model

Private equity firms recruit institutional investors – pension funds, insurance companies, foundations, endowment, sovereign wealth funds – for funds that they sponsor. A committee consisting of partners and principals in the PE firm is called the General Partner (GP) of the fund and makes all the decisions. Investors in the fund include institutional investors (pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowments and so on) as well as wealthy individuals. These investors are Limited Partners (LPs) and have no say in decisions about the fund’s financial activities. The LPs put up most of the equity in these funds, with the General Partner typically putting in one to two cents (occasionally as much as 10 cents) for every dollar the Limited Partners contribute. The LPs pay a management fee to the GP (the private equity firm), typically 2% annually of the money they have committed to the fund. The larger the fund, the larger are these no-risk payments to the GP (and thus the private investment firm). The GP also collects a lion’s share of any profits, typically 20% (but may be as high as 30 %) of the fund’s returns. And the PE firm typically contracts separately with the portfolio company for payment of monitoring fees and transaction expenses to the PE firm.

Large companies that are attractive targets for a private equity buyout possess considerable assets that can be used as collateral to finance the takeover of the company. A large amount of debt (referred to as leverage) is used to acquire the company for the fund’s portfolio, and it is the company, not the PE fund that owns it, that is obligated to repay this debt. Debt is a double-edged sword. For the PE fund, high debt and little equity used to acquire the portfolio company means that even a small increase in the enterprise value of the portfolio company translates into a large return to the PE fund. For the portfolio company, however, high debt increases the risk of financial distress or even bankruptcy and liquidation. Private equity is gambling with the future viability of the company when it loads it with debt. It is assuming that the company will be able to service the debt and refinance it as it matures. In the case of an unanticipated development, however, the portfolio company may find its margin of safety has been eroded by debt payments. It may be forced into bankruptcy. The private equity firm will lose at most its equity investment in the portfolio company, and often this has already been repaid via monitoring fees the PE firm collects directly from the portfolio company or from the proceeds of the sale of the portfolio company’s assets. The PE firm has little skin in the game; it’s the company, its workers, suppliers, creditors and customers whose livelihoods have been put at risk.

The Case of Retail Chains

Investments in large retail store chains provide private equity with rich opportunities for asset stripping, dividend payments and monitoring fees; and for many years, retail was the sweet spot for private equity. Retail is a cyclical business that can be undermined by a change in customer tastes or a downturn in the economy. To weather the inevitable bad times, retail chains typically have low debt burdens and own their own real estate. This protects them from having to pay rent or make high interest payments when things get tough. Retail is also a high cash flow business. These characteristics made retail an attractive target for private equity. There is room to load retail companies with lots of debt in the buyout. The real estate opens up the possibility of sale-leaseback transactions that benefit PE investors but leave the chain paying rent. And the high cash flow means the retail company is able to make payments directly to the PE firm for advisory services and transaction fees pursuant to an advisory agreement between the chain and the firm. It also facilitates the payment of dividends to the company’s PE owners.

Overloading retail chains with debt or selling off their real estate and burdening them with rent payments has made them financially fragile. Any change in the company’s prospects could lead to financial distress, bankruptcy and even, in extreme cases, to liquidation and the shuttering of stores. Toys ‘R Us, owned by KKR, Bain Capital and Vornado Realty Trust, is the poster child for this. But there are many other well- known examples of private equity-owned retail chains that closed all stores and laid off thousands of workers, left vendors with unpaid invoices, and creditors facing steep haircuts. They include Sun Capital-owned ShopKo, Alden Global Capital and Invesco-owned Payless ShoeSource, Bain Capital-owned Gymboree, Sun Capital-owned The Limited, Leonard Green-owned Sports Authority, Cerberus Capital Management-owned Mervyns Department Store and, most recently, the Michigan-based Art Van furniture store chain owned by Thomas H. Lee Partners.

Toys ‘R Us was still profitable at the time of its takeover in 2005 by the KKR, Bain and Vornado consortium, though its sales were flat and its profit and share price had fallen substantially compared with a decade earlier. At the time it was acquired, the toy store chain was valued at about $7.5 billion, including nearly $1 billion in debt. Its capital structure was 87 percent equity and a very manageable 13 percent debt. This was turned on its head when the chain was acquired by the financial firms for $6.6 billion – $1.3 billion in equity contributed equally by funds sponsored by those firms and $5.5 billion in debt. With the almost $1 billion in debt the chain was already carrying, its debt burden increased to $6.2 billion- a capital structure of 17 percent equity and 83 percent debt. Toys ‘R Us now had to make interest payments on this debt that exceeded $400 million in every year and $500 million in some (see Appendix A for details and sources). But for the investment funds that owned the chain, the low amount of equity they paid in would mean a very rich payoff if they exited the company at a profit in three to five years as planned. In 2010, five years after acquiring the company, KKR, Bain and Vornado attempted to return the company to the public market via an IPO. The effort failed however on concerns about the toy chain’s ability to refinance its high debt load.

It is this reckless loading of debt onto companies that the Stop Wall Street Looting Act would end by requiring the PE fund’s General Partner and the PE firm to be jointly liable with the company for repaying the company’s debts.

Toys ‘R Us would have been broadly profitable in the years following its takeover if not for the interest payments, which largely ate up the company’s profits. The chain struggled and ultimately collapsed under its massive debt load as creditors reasoned that their best chance to recoup some of their money was to liquidate the business and sell off its assets. 900 communities lost an important retail anchor as the stores closed, 33,000 workers lost their jobs., vendors and landlords went unpaid, and creditors lost money they had loaned to the retail chain. The limited partners in the PE funds had their investment in Toys wiped out. But KKR, Bain and Vornado managed to make money despite not creating – and, in fact, destroying – value.

The bankruptcy protections for workers in the Stop Wall Street Looting Acy include mandatory severance payments for workers who lost their jobs in the bankruptcy, which would provide further protection not just for workers but for businesses that have a stake in the survival of companies like Toys. We cannot know whether Toys’ creditors would have made a different decision if seniority-based severance payments to 33,000 workers, some with decades of service, had to be paid out in the case of liquidation. But it would definitely have altered the calculus.

As for the funds that owned the chain, they each put in $433 million in equity when Toys was purchased. Bain contributed 10 percent of the equity in its fund or $43 million. KKR put up $10 million (2.3% of the equity in its fund). Vornado’s contribution is unclear. At the time of its acquisition, Toys ‘R Us had entered into an advisory agreement with each of the three sponsoring firms (not the funds) that specified payments that Toys ‘R Us would make to KKR, Bain and Vornado for advisory services. Over the life of the agreement, Toys ‘R US paid Bain, KKR and Vornado a total of $185 million for these services, or $61 million each. Bain did not agree to share these payments with its limited partners so net of its equity contribution, it had a gain of $17 million. KKR had agreed to share 58% of its advisory fees with its limited partners, leaving it with $24 million. Net of its $10 million contribution to its PE fund, KKR had a gain of $14 million. It’s not clear how much of Vornado’s $61 million was a net gain. In addition to the advisory fees, the three companies collected a total of $8 million in expense fees, $128 million in transaction fees, and $143 million in interest on loans they had made to Toys ‘R Us. In total, Toys ‘R Us paid the firms that owned it $464 million. In addition, some of the chain’s real estate was sold to Vornado and leased back by the stores, resulting in a total of $73 million paid to Vornado in rent (details and sources in Appendix A). Toys’ PE firm owners made a profit despite recklessly endangering the toy store chain.

Buy and Build PE Model

“Buy and build” is another strategy that private equity uses to make money. In this strategy, the private equity firm acquires a company in a leveraged buyout and then expands the company – now called a platform company – through a series of debt-fueled horizontal mergers with its smaller rivals. The strategy has several advantages for the PE firm. It enables the PE firm to establish local monopolies and reduce competition. Its portfolio company can exploit its dominance in the market to increase its profits by raising prices and/or degrading the quality of its services without fear of competition for its customers. And adding-on smaller rivals is a faster path to revenue growth than investing in the original company. A growth strategy of using leveraged buyouts to add-on smaller competitors to the original portfolio company is more lucrative than investing in the original company and taking the time to allow it to grow organically.

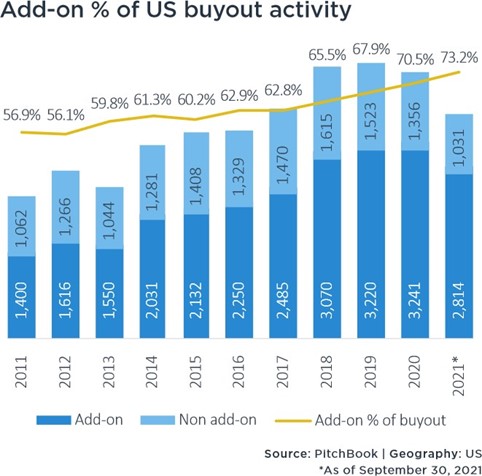

Figure 1

The use of add-ons by PE firms has become a popular strategy. It has grown as a proportion of leveraged buyout activity across all segments of the economy, from 56.5% of buyouts in 2009 to 70.5% in 2020 and is on a path to reach 73.2%, an all-time high, in 2021. The key to the strategy is to pursue healthy add-on acquisitions in highly-fragmented markets and utilize the platform company’s access to leveraged loans to expand into hundreds of smaller, local territories through multiple add-on acquisitions.

Physician Staffing Firms

A familiar example of how PE firms extract wealth and make money using the buy and build strategy comes from the world of physician staffing firms. Private equity-owned emergency room physician practices and the use of surprise billing to collect sometimes astronomical payments from patients who are treated by these doctors have raised concerns among consumers and patient advocates. These are patients who are treated at hospitals that are in their insurance networks by out of network emergency doctors on private equity-owned company payrolls. Private equity firms have been actively acquiring doctors’ practices through leveraged buyouts and rolling them up into large, debt-burdened physician staffing firms, a form of Managed Services Provider (MSP). PE firms have consolidated these previously fragmented markets, and are now dominant players able to exploit the market power of their MSPs to increase prices paid by patients and private insurance payers. Many of the acquisitions have been too small to trigger anti-trust oversight. But cumulatively, they have led to large, national consolidated doctors’ practices able to exercise monopoly pricing power in local health markets.

In addition to increased market power in pricing emergency room procedures, the takeover of doctors’ practices affects the practice of emergency medicine. Physicians are shielded from dealing with billing and collections. But on the flip side of this, the PE-owned staffing firms often inflate prices for treatment of patients, while doctors on PE payrolls do not have a right to see invoices sent out in their names. They are, thus, unable to serve as a check on fraud or exploitation of patients. From the point of view of the private equity firm, physicians are the major expense, and they would like to see revenue per physician increase or the cost of employing these doctors reduced. Pressure is on these emergency medicine doctors to use charting and documentation to maximize payments to the staffing firm, and to increase the number of patients they see per hour. PE firms also decrease the number of emergency medicine physicians on staff and increase the number of lower cost nonphysician practitioners (NPPS) in emergency rooms, increasing the length of time that patients in ERs wait to see a doctor. Not only do these practices reduce the employment of trained physicians in emergency rooms, but the number of NPPs that each physician is tasked with overseeing is increased. There are few complaints about working conditions or patient care from doctors on private equity payrolls. Doctors employed by PE-owned physician staffing firms put their jobs on the line if they speak up about their concerns. They can be fired on short notice and given no opportunity to contest the termination. When the focus is on making money, doctor staffing levels decline, the pressure on emergency medicine doctors increases, and the quality of patient care suffers.

Most states require that physician practices be owned by doctors and make the corporate practice of medicine illegal. Private equity firms get around this requirement by having the physician practices nominally owned by a medical practitioner. In recent legal proceedings against an emergency medicine staffing firm, it was revealed that a single physician was on record as owning and managing 270 to 300 physician practices across 20 states. This was clearly a sham arrangement to hide PE’s role in the illegal corporate practice of medicine. While a physician nominally owns the doctor practices. all of the assets of the practices, from the chairs in the waiting room to accounts receivable, are owned by the physician staffing firm. The Stop Wall Street Looting Act would require that all entities receiving federal money – so nearly all entities in health care –to reveal their ultimate owners.

The initial focus of private equity acquisitions was on hospital-based specialties like emergency medicine and anesthesiology. The largest physician staffing companies in these specialties are Envision Healthcare and TeamHealth, MSPs acquired respectively by funds of private equity firms KKR in 2018 for $9.9 billion and the Blackstone Group in 2016 for $6.1 billion. The two staffing companies have cornered 30 percent of the market for outsourced emergency medicine doctors, and collectively employ almost 90,000 health care employees that fill a variety of roles. Debt-financed consolidation of emergency medicine practices has enabled these PE firms and their MSPs to dominate the physician staffing industry. Multiple rounds of private equity ownership, punctuated by IPOs and a return to public markets, have left these companies with high debt loads. Envision’s $5.45 billion loan is due in October 2025; TeamHealth‘s loan is due in January 2024. The companies have relied on high fees for doctor services and surprise medical bills to provide sufficient revenue to meet debt obligations.

Envision came under heavy scrutiny for the huge out-of-network surprise medical bills it sent to ER patients. A team of Yale University health economists examined the billing practices of EmCare, Envision’s physician staffing arm. They found that when EmCare took over the management of hospital emergency departments, it nearly doubled its charges compared to the charges billed by previous physician groups. TeamHealth, the Yale University economists found, took a somewhat different tack. It used the threat of surprise billing to gain high reimbursements from insurance companies to keep its doctors in-network.

In a victory for patients and the health care system, Congress passed the No Surprises Act in December 2020. The act bans the practice of sending surprise medical bills to patients beginning on January 1, 2022. In a concession to the private equity-owned staffing companies, such bills can still be sent to insurance companies, and disputes over payment are subject to arbitration. But arbitrators are instructed to begin from what in- network doctors are paid for procedures rather than from the often massively inflated charges from the PE- owned doctors’ practices. PE-owned practices may still receive somewhat higher payments than other doctors, but the expectation is that these payments will be much more in line with what others receive, and a great savings to the health care system. The effects of these measures on the massive amounts of debt owed by TeamHealth and Envision coming due in 2024 and 2025 are currently not known. But default would surely throw the healthcare system into chaos.

More recently, the corporate practice of medicine has grown as private equity has turned its attention to specialties that are not hospital-based. Dermatology is the bleeding edge of this development, having been among the earliest to attract private equity’s attention. But dermatology has been quickly followed by gastroenterology, orthopedics, ophthalmology, women’s health and other specialties that cater to patients with private insurance, assuring a more lucrative payer mix. The effects of Covid-19 and proposed spending in President Biden’s Build Back Better bill have further fueled private equity’s already considerable interest in home health care, hospice services, and behavioral health – the latter to treat both victims of the opioid crisis and those suffering mental health problems caused by the isolation and disruption of the pandemic. Patient care is likely to suffer as the PE owners hold the medical specialists, now their employees, to metrics that increase revenue per patient and reduce costs. The substitution of less expensive Nonphysician Practitioners for physicians and an increase in the number of NPPs a physician is required to supervise are likely to affect patient care. Requiring these practices to identify private equity firms as their owners, as the Stop Wall Street Looting Act requires, will enable patients to make informed decisions about where they want to be treated.

A similar situation is emerging in the accounting industry. Like physician practices, accounting firms have legal requirements that require that certified public accounting firms be owned by certified public accountants (CPAs). An ‘attest’ service – in which a CPA conducts an independent review of a company’s financial statements and attests to their accuracy – can only be conducted by a CPA-owned firm. As with health care, the accounting business is largely recession proof. It’s a predictable business with high cash flow and little volatility. So, it is not surprising that PE is looking for a work around that will let it take over large, successful accounting firms.

In mid-September 2021, PE firm Lightyear Capital announced that it is buying a large stake in Schellman & Co., a top CPA firm, ranked 65th in the country in the Accounting Today 2021 list. Schellman is being split into two entities – a CPA firm that will perform attest services and a new company, in which the PE firm is the majority owner, that that will provide tax and consulting services. A month later, PE firm TowerBrook Capital Partners announced it would take an ownership stake in top 20 accounting firm EisnerAmper. It again split the company into two entities and took a majority stake in the consulting business. These large accounting firms with high cash flow can be loaded with debt that will be used to acquire smaller competitors. This has the potential to crush competition and establish the dominance of these accounting firms in local and national markets. Main Street businesses are likely to suffer from a lack of alternatives when it comes to having tax and auditing work done. They might want to be informed about whether private equity has a stake in an accounting firm with which they do business.

The Paradox of Private Equity

The “paradox of private equity” refers to the finding that smaller private equity funds often outperform mega funds and tend to deliver the best returns to investors, while the bulk of the money invested in private equity flows to large funds and mega funds. Better performance of smaller funds is actually not surprising. In our research, Rosemary Batt and I found that smaller PE funds typically acquire small and medium-sized enterprises that can benefit from the access to financing and improvements in operations and business strategy that private equity firms can provide. These enterprises have relatively little in the way of assets that can be mortgaged, which rules out the excessive use of debt to acquire them. In addition to lower levels of debt, these PE funds provide access to financing to upgrade operations, advise on implementation of modern IT, accounting, and management systems, and appoint board members that can assist with business strategy. These improvements in governance, operations, and strategy create value for the companies and the economy.

But while the large majority of PE deals are carried out by smallish funds buying out smallish companies, large or mega funds receive he lion’s share of funds from PE investors. Limited partner investors have committed billions of dollars to massive funds sponsored by a relative handful of PE firms. In the five years ending in April of 2021, the top 300 PE firms worldwide raised a total of $2.25 trillion. This is an increase of 13% from the previous 5-year period. Blackstone retained its position as top fund raiser – its funds raised $93.2 billion over the five years, with KKR not far behind. Eight of the top 10 (out of 300) funds are U.S. firms.1 The flow of capital to the largest PE firms in the aftermath of the pandemic is even more extreme than when the Stop Wall Street Looting Act was first introduced, making its passage all the more urgent. Capital raised by individual funds in the first three-quarters of 2021 make clear that mega funds dominate fund raising. PE firm Hellman & Friedman raised $24.4 billion for its 10th fund while KKR is closing in on $18.5 billion for its North America fund and the Carlyle Group has announced plans to raise $27 billion for its next fund – the largest private equity fund ever if, as expected, they reach their goal. Silver Lake Partners whose latest fund closed this year at $20 billion, Clayton, Dubilier & Rice at $16 billion, and Bain Capital at nearly $12 billion are also among the mega funds at the top of the fund-raising pyramid. Twelve mega funds have closed through August, with a quarter of the year still left. All of this money needs to be deployed in just a few years.

Mega funds have incentives to acquire large companies even if the returns are mediocre compared with smaller companies. A mega fund has a huge amount of capital it needs to deploy in a relatively short period of time. This is more easily done if the fund acquires a few very large companies. (The exception, as noted earlier, is when a PE fund buys up small competitors and adds them onto a large company it already owns, flying below the radar of antitrust regulators as it creates a national powerhouse.) PE funds plan to exit their acquisitions in three to five years. This is too short a time horizon to ‘turn around’ a struggling company. In contrast to the myth that PE funds buy troubled companies, it turns out that attractive acquisition targets tend to be successful businesses. Medline Industries, a family-owned medical supply company, sold for $34 billion in June of 2021 in a club deal in which Blackstone, Carlyle, Hellman & Friedman, and GIC participating. Clearly, a company that sells for $34 billion to some of the biggest names in private equity offers few opportunities for improvement.

Large, successful companies present few opportunities for creating value by improving operations or business strategy. They nevertheless present opportunities for PE funds to load them with debt, extract wealth via financial engineering, and make PE partners rich. Millionaire and billionaire partners in private equity firms make money even when the funds they sponsor do not create value and even when they destroy it. Good jobs have been lost and inequality has worsened.

Meanwhile, private equity firms contend that their freewheeling behavior results in returns that beat the stock market by a wide margin and help fund retirees’ pensions. They caution against killing the goose that lays the golden eggs. This is an argument that might once have made sense, but no longer. Studies by finance professors find that since 2006, the median private equity fund has just tracked the market.2

Conclusion

In ways large and small, Main Street is being pillaged by Wall Street’s largest private investment firms. Factories and stores have closed as wealth has been extracted, hollowing them out and leaving them bereft of the resources they need to invest in the technologies and worker skills required for success in the 21st century. PE firms view the companies their funds acquire for their portfolios as financial assets whose purpose is to provide returns to the fund and its private equity investors, not as operating companies that employ workers, produce valuable products for customers, and foster sustainable growth.

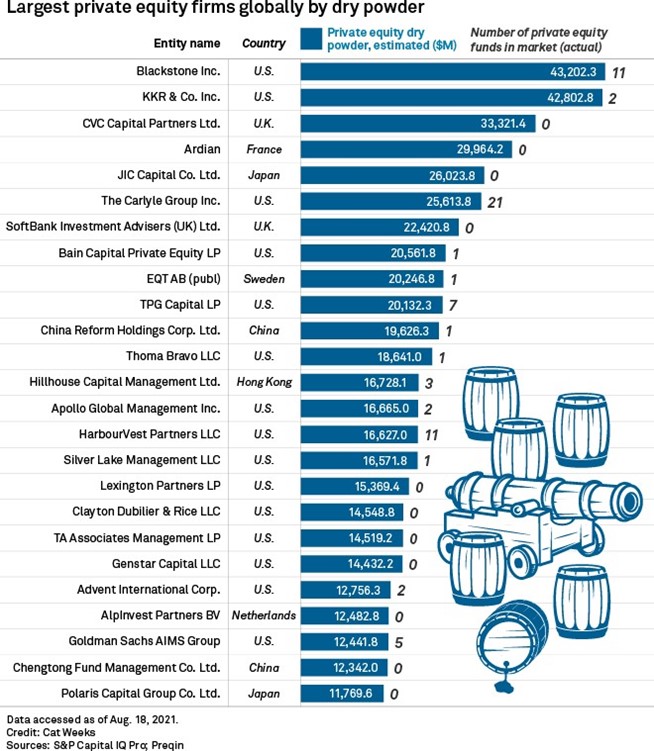

Private equity is poised to buy up key segments of the U.S. economy. The rising tide of capital flowing into PE funds has left them sitting on piles of dry powder. They are now ins a better position than ever to buy up and hollow out large parts of the U.S. and global economies. Estimates of how much global dry powder PE firms are sitting on varied from $1.5 to $2 trillion in August with four months to go in 2021. In September 2020, U.S. buyout funds had $746 billion in dry powder (See Figure 2). The figure below shows the amounts of dry powder that some of the largest PE firms are getting ready to deploy.

In the U.S. PE firms have set their eyes on everything from health care to single family homes, and are even trying to figure out how to make money from the chaos in fossil fuels as attention turns to combating climate change. We need the Stop Wall Street Looting Act now to provide incentives to PE funds sitting on many billions of dollars to use them in ways that create good jobs, high-quality goods and services, and help build a sustainable economy that supports the planet. No one will object if they also make an honest profit.

Figure 2

1 They are Blackstone, KKR, Carlyle, Thomas Bravo, Vista Equity Partners, TPG, Warburg Pincus, and Neuberger Berman Private Markets https://www.privateequityinternational.com/database/#/pei-300

2 Eileen Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt. 2018. “Are Lower Private Equity Returns the New Normal?” in Michael Wright et al. (editors), The Routledge Companion to Management Buyouts, Routledge. Robert S. Harris, Tim Jenkinson, and Steven N. Kaplan.2015. “How Do Private Equity Investments Perform Compared to Public Equity?” Journal of Investment Management. Darden Business School Working Paper No. 2597259, June 15. Available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2597259; Jean-Francois L’Her, Rossitsa Stoyanova, Kathryn Shaw, William Scott and Charissa Lai. 2016. “A Bottom-Up Approach to the Risk-Adjusted Performance of the Buyout Fund Market.” Financial Analysis Journal, 73(4), July/August. https://www.cfainstitute.org/en/research/financial-analysts-journal/2016/a-bottom-up-approach-to-the-risk-adjusted- performance-of-the-buyout-fund-market; Ludovic Phalippou. 2020. “An Inconvenient Truth: Private Equity Returns and the Billionaire Factory.” Journal of Investing, Volume 29, December. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3623820

Appendix

| Fiscal Year | Advisory fee | Expenses | Transaction fee | Interest on debt | Total | Vornado lease agreements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | $4 | $81 | $85 | |||

| 2006 | $19 | $9 | $28 | |||

| 2007 | $17 | $26 | $43 | |||

| 2008 | $17 | $1 | $25 | $43 | ||

| 2009 | $15 | $1 | $7 | $18 | $41 | $7 |

| 2010 | $19 | $1 | $29 | $15 | $64 | $9 |

| 2011 | $20 | $1 | $4 | $14 | $39 | $9 |

| 2012 | $21 | $1 | $7 | $8 | $37 | $10 |

| 2013 | $22 | $1 | $15 | $10 | $48 | $8 |

| 2014 | $17 | $1 | $32 | $10 | $60 | $8 |

| 2015 | $6 | $1 | $7 | $14 | $8 | |

| 2016 | $6 | $1 | $7 | $8 | ||

| 2017 | $2 | $0 | $2 | $6 | ||

| Totals | $185 | $8 | $128 | $143 | $464 | $73 |

Note: Struck through transaction fees were accrued but later waived

Source: SEC Form 10-K, links for each year in Table.

| Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interest expenses (US$ millions) | 503 | 419 | 403 | 440 | 514 | 432 | 464 | 517 | 447 | 426 | 455 |

Source: SEC Form 10-K; See for example, p. 25 of https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1005414/000100541417000011/tru201610k.htm