Article

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

It has been eight years since the Honduran military removed democratically elected president Manuel Zelaya from office. The post-coup period was characterized by social turmoil, violent repression by state forces, and a breakdown in the rule of law.

In November 2013, shortly before Honduras’ last presidential elections, CEPR published a report on the country’s economic situation since the 2009 coup showing that economic growth had slowed, social spending had decreased, and unemployment had worsened.

On Sunday, November 26, Honduras will again be holding presidential elections. In this post, we provide a brief, fresh overview of the macroeconomic and social indicators in Honduras since the coup, in order to help understand the economic context in which these elections will unfold.

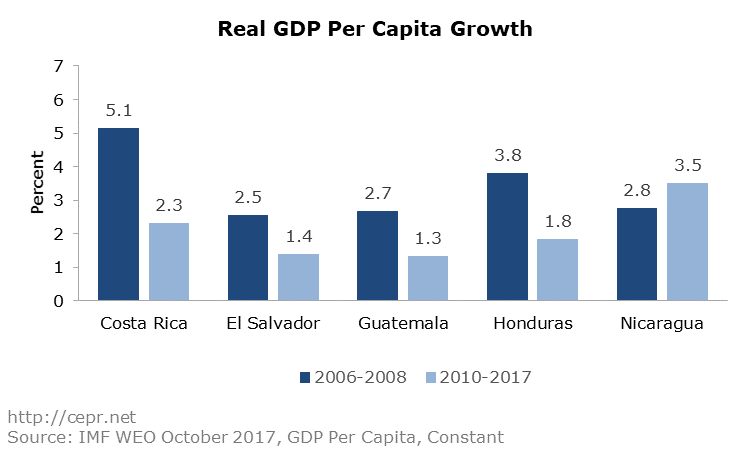

1. Economic Growth: In the years preceding the coup, Honduras averaged 3.8 percent annual per capita GDP growth. Since 2010, this has dropped to 1.8 percent. The figure below compares Honduras’ per capita GDP growth with the region. Though higher than regional peers Guatemala and El Salvador, the decline relative to the pre-coup period was deeper in Honduras.

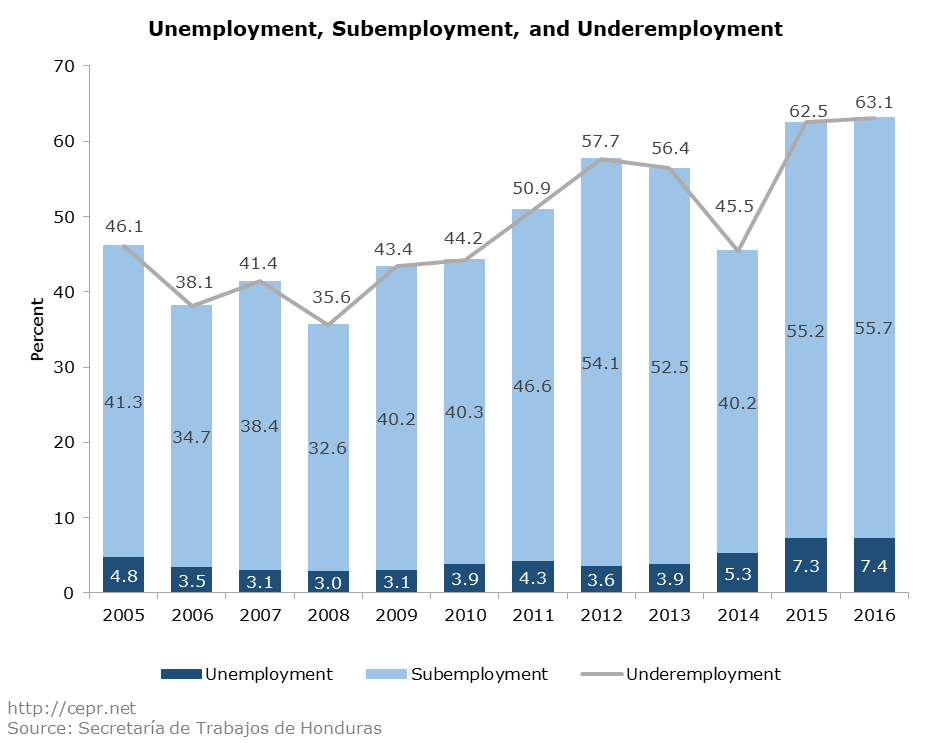

2. Unemployment: The labor market has gotten considerably worse since the 2009 coup. Unemployment reached a low of 3.0 percent in 2008, but has steadily increased to 7.4 percent in 2016. These numbers only tell part of the story. Developing countries often follow a pattern of low formal unemployment rates and high underemployment rates. The lack of a social safety net often forces people in developing countries to take any work they can find, regardless of quality or equitability. Subemployed workers either receive less than the minimum wage, or work fewer hours than they desire. The graph below shows unemployment, subemployment, and total underemployment, the sum of unemployment and subemployment, since 2005. After falling 10.5 percentage points from 2005 to 2008, underemployment has since increased by 27.5 percentage points. More than 63 percent of the economically active population is either unemployed, working for less than minimum wage, or working fewer hours than desired.

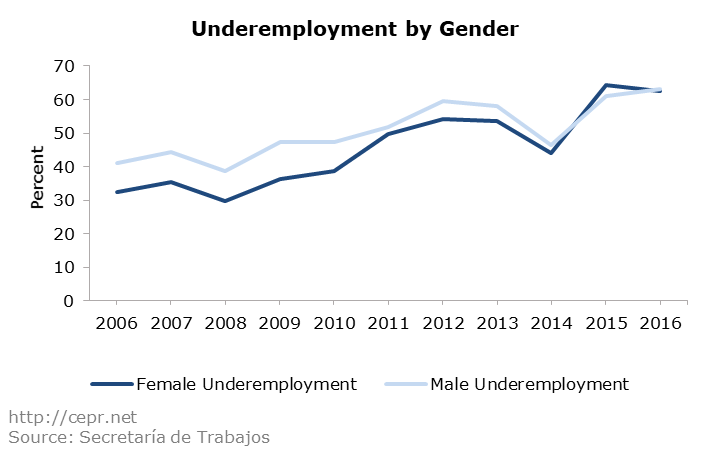

3. Unemployment by Gender: The employment situation has been particularly devastating for women. Historically, the underemployment rate for women has been significantly lower than that for men. Since 2008, however, the female underemployment rate has more than doubled, and in 2015, for the first time, the rate for women actually surpassed that for men though there was a slight improvement in 2016.

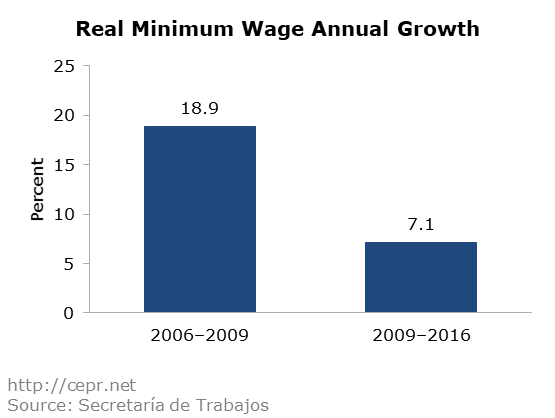

4. Minimum Wage: Increasing unemployment and underemployment has occurred in a context of a minimum wage that is rising far slower than it did in the years preceding the coup. President Manuel Zelaya drastically increased the minimum wage from 2006 to 2009. During that time period, the average annual real minimum wage increase was 18.9 percent. Since the coup, however, the minimum wage has been increasing far more slowly, at just 7.1 percent.

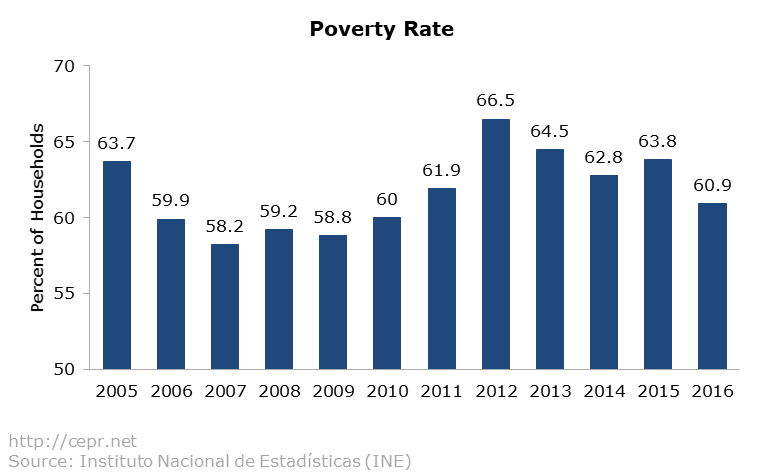

5. Poverty: After the coup, poverty skyrocketed in Honduras. In 2009 before the coup, 58.1 percent of households were in poverty. By 2012, that figure has risen to 66.5 percent. Though that figure has decreased over the last four years, it remains above its pre-coup level at 60.9 percent. This decline can be at least partially attributed to policy choices, such as the slashing of social spending following the coup.

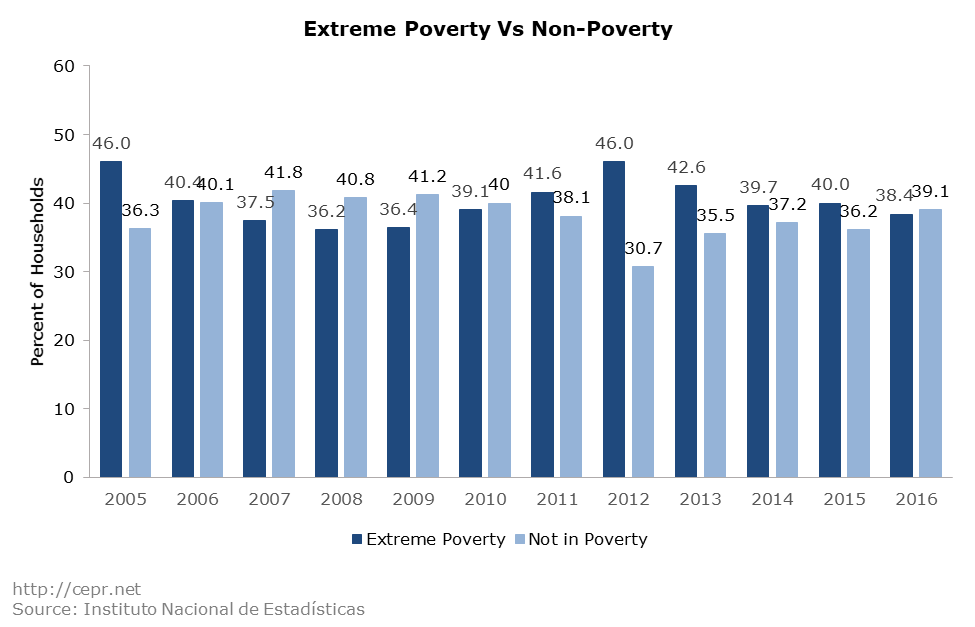

6. Extreme Poverty: Not only has Honduras experienced consistently high poverty rates, but the majority of this is extreme poverty. The graph below compares the percent of the population in extreme poverty to the rate of those not in poverty at all. As can be seen, from 2007 to 2009 the number of people out of poverty surpassed those in extreme poverty for the first time in years. This trend was reversed after the coup, and from 2011 to 2015 extreme poverty was greater. In 2016, extreme poverty dropped below nonpoverty levels for the first time in years, though it remained above its pre-coup level.

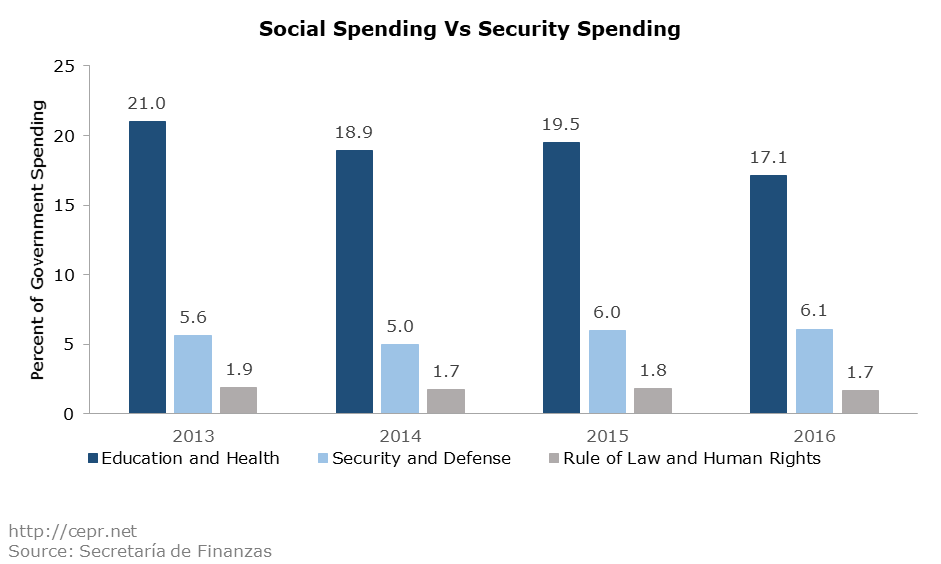

7. Spending Priorities: After the coup, social spending especially on education decreased. Under the Juan Orlando Hernández administration, this trend has continued, while spending on the military and public security has increased. The graph below also shows the very small percentage of total public spending that is allocated to the Rule of Law & Human Rights. Though spending for education and health remains far higher than for defense, as a percent of total spending it has decreased significantly from 21 percent to 17.1 percent. Despite the continuing flagrant abuse of human rights in the country and the lack of rule of law, especially since the coup, the paltry amount spent in these areas is especially alarming.

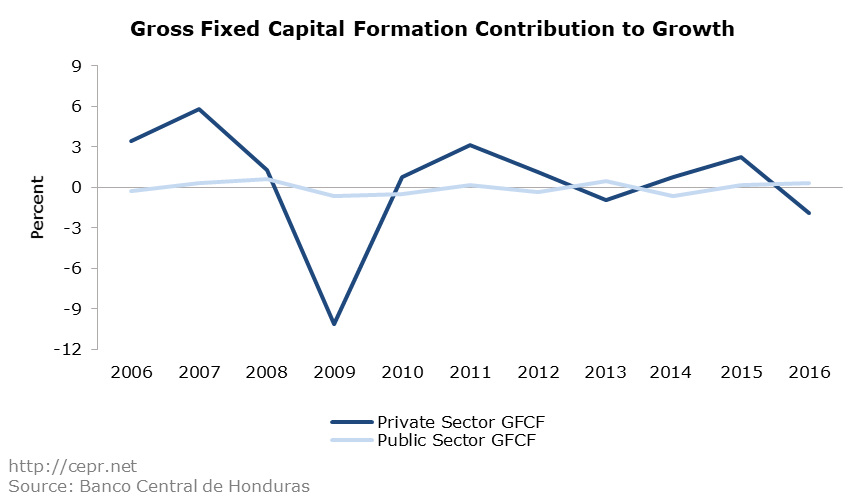

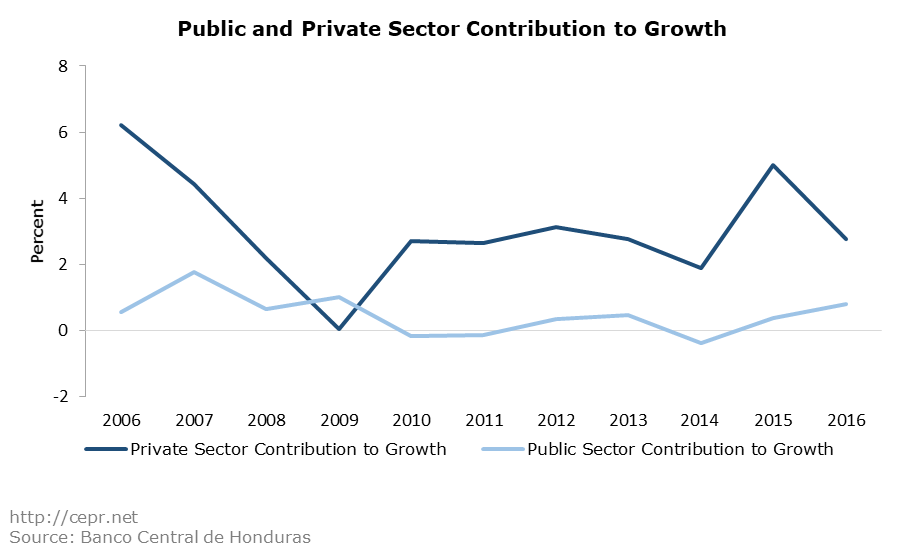

8. Public and Private Spending: Honduras was in a strong position to increase government spending in the wake of the 2009 global economic recession and its coup d’etat. However, public consumption’s contribution to GDP growth, as shown in the graph below, decreased after 2009 and turned negative in 2010 and 2011. Though it has returned to a positive level more recently, it is still below its pre-coup levels. The government has instead prioritized private sector development to spur economic growth; however, for most of the post-coup years private sector spending contributed less to GDP growth than in the years prior. After a spike in 2015, it fell precipitously in 2016.

9. Public and Private Capital Formation: A similar trend can be seen by looking at the contribution to GDP growth of Gross Fixed Capital Formation. The majority of investment in Honduras is undertaken by the private sector, which accounts for more than 85 percent of total gross fixed capital formation. As can be seen in the graph below, private sector investment plummeted during 2009 and has not recovered to pre-crisis levels. Though the Honduran government is relying on the private sector to spur development, private sector gross fixed capital formation actually contributed negatively to GDP growth in 2016.