How a Colombian Ex-President Went to Bat for Trump in Florida

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

Latin Americans are used to the US government interfering in their politics. Over the years, the US has helped orchestrate a number of coups throughout the hemisphere, most notoriously the 1954 ouster of Guatemala’s Jacobo Árbenz, and the 1973 military coup against Chile’s Salvador Allende. But there are far more recent examples of meddling, including US interference in Haiti’s 2010 election and State Department actions that helped a coup succeed in Honduras in 2009.

Last year, the US got a small taste of its own medicine when several high-profile Colombian politicians from the ruling right-wing Centro Democrático party, including a former president, dipped their toes into the electoral waters of the Sunshine State. It has now been acknowledged in various US, Colombian, and international outlets that, both openly and behind the scenes, Colombian right-wing actors bet heavily on Trump’s campaign in Florida last year, and contributed to his victory in the state, despite Trump’s national loss.

The seeds of this effort stretch back several years. Former president Álvaro Uribe (2002–2010), a right-wing leader who US officials believed had ties to Colombian paramilitary groups responsible for human rights atrocities, has spent years forming extensive contacts with various Repblican politicians in Florida, from Senator Marco Rubio to freshman Congresswoman Maria Elvira Salazar, whom Uribe endorsed during her congressional campaign last year. Senators from Uribe’s Centro Democrático party — including Juan David Vélez and María Fernanda Cabal — openly campaigned for Trump, while Trump’s advisors, including Cuban-American Mercedes Schlapp, took a page from Uribe’s campaign playbook by helping to engineer anti-socialist messaging in an attempt to garner votes for Trump from Cuban, Colombian, and Venezuelan diaspora communities in South Florida. These efforts represent an unprecedented level of intervention by the Colombian Right in US politics and an effort by the Colombian government to expand its foreign policy ambitions by influencing electoral outcomes in other countries throughout the Americas.

Uribe himself is a highly polarizing figure in Colombia and the region. Though he left office with high approval ratings, his administration oversaw massive human rights abuses. Under Uribe, Colombian military and paramilitary groups, often working in tandem, were involved in numerous massacres of unarmed civilians. A number of Uribe’s family members and close allies have reportedly had close relations with paramilitary forces and Uribe himself allegedly helped create one of Colombia’s most brutal paramilitary groups in the 1990s.

Uribe has continuously campaigned against the peace agreement with the FARC insurgency, and he and his allies have sought to block its implementation since its approval by Colombia’s congress in 2016. Hindered by term limits that prevented him from again seeking the presidency, Uribe chose former Inter-American Development Bank official Iván Duque as his standard-bearer for the 2018 election, and Duque — who won the election — is widely considered to be Uribe’s stand-in.

Since leaving the presidency, Uribe has become embroiled in a variety of corruption scandals linked to his time in office, and was sentenced to house arrest in 2020. Within months he was released, reportedly due in part to strong pressure exerted by then US vice president Mike Pence and Florida Republicans. President Trump Tweeted a congratulatory message to Uribe when his arrest was suspended.

It should come as no surprise then that Uribe, Duque, and the Colombian Right threw in their lot with Trump and Florida’s Republicans. They share the common goals of ousting Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro, by nearly any means. Trump, in addition to implementing sweeping new economic sanctions against Venezuela, took a hard-line approach involving threats of military intervention and vigorous support for a possible coup against Maduro by Venezuela’s armed forces. Duque is likewise a Venezuela hawk who has called for more sanctions on Venezuela, and has been accused of allowing dissident Venezuelan military troops to train in Colombian territory and to launch an ill-fated invasion of Venezuela in early 2020.

Given this close alignment of views on Venezuela, it isn’t surprising to see Republicans in South Florida embrace some of the charged rhetoric used by the Right in Colombia. Alongside allegations of “socialism” used against Florida Democrats, the charge of castrochavismo (“Castro-Chávism,” referring to a supposed joint political project linking the Castro brothers and Hugo Chávez) has become increasingly frequent. In October 2016, following the defeat of the peace deal in the 2016 referendum, Uribe campaigned against the peace agreement’s ratification by the Colombian Congress at the popular Colombian restaurant Mondongo’s in heavily Venezuelan and Colombian Doral, Florida. Flanked by Republican politicians including Senator Marco Rubio and Congressman Mario Diaz-Balart, Uribe whipped up a crowd of Colombian expats by warning that castrochavismo would come to Colombia were the agreement ratified. Several reports have suggested this was the moment when South Florida Republicans realized that the castrochavismo label might prove effective among Cuban, Colombian, and Venezuelan-Americans — ever more important voting blocs in Florida. As Colombian-American political analyst Juan Pablo Salas put it: “The lessons that Uribismo learned from the referendum in Colombia have been translated to Republicans, who have had no problem applying them in South Florida.”

It is no coincidence then that the 2018 campaigns in Florida and Colombia featured nearly identical red-baiting tactics: Republican candidate Ron DeSantis frequently referred to Democrat Andrew Gillum as a “socialist,” and warned that if elected Gillum would turn Florida into a “second Venezuela.” Uribe had himself used the same exact rhetoric before, warning in 2016 that the peace deal would transform Colombia into a “second Venezuela,” and fear mongering over left politicians seeking to turn their countries into “another Venezuela” has become a common right-wing political tactic throughout Latin America, employed against figures including Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico and Fernando Haddad in Brazil. Unsurprisingly, when left politician Gustavo Petro ran against Duque for the presidency in 2018, Colombians were told that Petro, if elected, would do the same.

At the same time DeSantis was calling Gillum a dangerous “socialist,” Duque was using the same rhetoric against Petro, 1,500 miles away. DeSantis went on to narrowly defeat Gillum, while 70 percent of Colombian-Americans who voted in the Colombian election from abroad voted for Duque over Petro, as compared to 54 percent in Colombia. The supposed menace of Maduro’s (and before him Chávez’s) Venezuela has increasingly become a useful tool not only in Colombia, but in Florida and US politics as well.

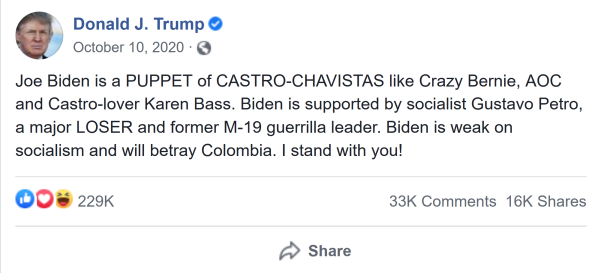

The red-baiting only grew more shrill in 2020, with the Trump campaign running multiple ads claiming that Joe Biden was the preferred candidate of the Venezuelan government. Trump likewise attacked Biden for supposedly being supported by Gustavo Petro, announcing: “Biden is weak on socialism and will betray Colombia,” in a transparent effort to attract pro-Duque Colombians living in Florida and elsewhere. Schlapp, the Trump advisor, released a video in which she claimed that Gustavo Petro supported Biden, and that “Biden has surrounded himself with socialists like [Petro], including Bernie Sanders and the communist [sic] Karen Bass.”

At the same time, Trump received the endorsement of members of Uribe’s party, including Senator María Fernanda Cabal and Representative Juan David Vélez, who represents Colombians abroad, while Uribe himself weighed in to endorse the ultimately victorious Maria Elvira Salazar’s campaign for a congressional seat representing suburban Miami.

By all accounts, these efforts worked well among Colombian, Venezuelan, and Cuban voters in Florida. Some of Trump’s largest gains in the entire country were in South Florida, and especially in heavy Colombian and Venezuelan towns like Doral and Weston (Trump improved in Doral by over 30 percent compared to his 2016 performance). Overall, Trump won Florida by 3.3 percentage points (compared to 1.2 percentage points in 2016), while the GOP picked up two House seats. Exit polls reported that Trump won 46 percent of the Latino vote in Florida, a much higher proportion than his national total (32 percent). It should also be emphasized that Trump’s overall margin in Florida expanded while he actually lost ground among white voters, as compared to 2016 (62 percent, vs. 64 percent in 2016).

It is clear that the Colombian Right, led by Álvaro Uribe and Iván Duque,is prepared to go to significant lengths to bolster its allies abroad. As one Colombian analyst argued: “Duque has seriously compromised the privileged relationship he has with the United States.” Indeed, Democrats took notice of these efforts: two Democratic Congressmen, new chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Gregory Meeks, and Ruben Gallego penned an October 2020 op-ed calling on Vélez and Fernanda Cabal to refrain from further campaigning for Trump: “we have a very clear message for our Colombian counterparts: Show us the respect of staying out of our elections.”

That was last year. This year, Duque and his right-wing allies are at it again: this time in neighboring Ecuador, where presidential elections are underway, and a left-leaning candidate is the front runner.

Coming up next: “How the Colombian Right’s Smear Campaign has Rocked Ecuador’s Presidential Election”