Article

Surcharge Reform: Three Scenarios for the IMF Board

Article

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

In April of this year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) formally announced that it would be carrying out a review of the IMF’s controversial “surcharge” policy — punitive fees that are levied on countries whose debt to the IMF exceeds a certain threshold. Over the last four quarters, the IMF has imposed over $1.9 billion in surcharges to 23 countries.

Given that these fees are counterproductive and unfair and that there are historical precedents for their elimination, CEPR and many other economic experts have consistently advocated for the complete discontinuation of the surcharge policy. Most recently, a group of US legislators — including a large share of the influential Financial Services Committee of the House of Representatives — has strongly urged the US Treasury to support the removal of surcharges. However, it has recently been reported in the media that three key variables are being considered for surcharge reform. We thought it could be useful to provide a quantitative illustration of the options that are being discussed by the members of the IMF Executive Board.

The three key variables for a potential reform are: (1) the threshold for the application of surcharges, (2) the surcharges’ rates, and (3) the level of the base rate through a change in the lending margin. The proposed scenario simulation shows how alternative reforms could affect the IMF’s financial position and how much debt relief could be provided to emerging and developing countries.

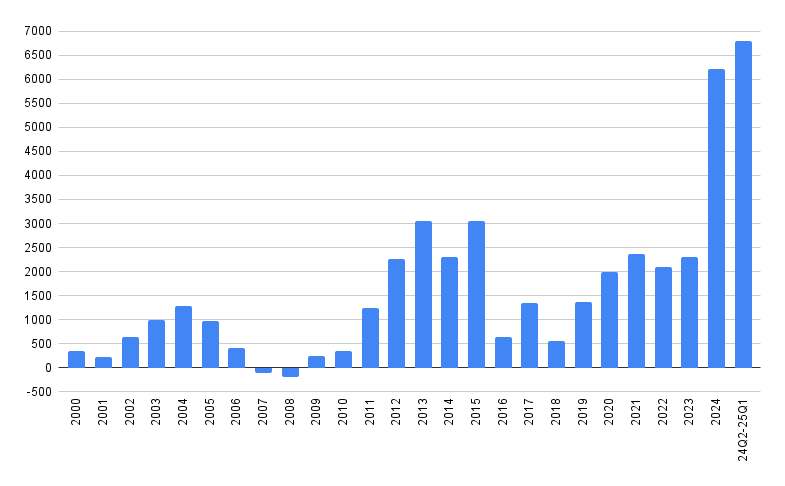

It is important to note that in financial year (FY) 2024 (ending in April 2024) the IMF had a record-breaking net income of $6.3 billion.1 Over the last 12 months (August 2023–July 2024), the IMF had $6.8 billion in net income (see Figure 1 below). This is equivalent to three times the average earnings in the last four years (FY 2020–2023) and five times the average earnings between FY 2000 and 2023. The IMF’s net income in FY 2024 was six times larger than the World Bank Group’s International Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s 2023 income, although the bank’s outstanding loans are double the size of those of the IMF.

We used quarterly IMF Finances data and compared actual observed surcharge payments with estimated payments should changes to this policy were to be introduced, using the period from August 2023 to July 2024 as a reference. Unless specified otherwise, the following scenarios are ceteris paribus estimates based on the last consecutive four quarters of available data.

Our country-by-country historical and projected surcharges dashboard can be visualized here.

The IMF levies surcharges on loans to countries whose General Resources Account (GRA) debt exceeds a certain threshold, defined in proportion to each country’s quota at the IMF. Following the IMF’s last quota increase in 2016, the threshold was reduced from 300 percent of a country’s quota to 187.5 percent. This mainly affected middle-income countries, as we discussed in our 2021 report. Given this historical precedent, one potential outcome of the surcharges review would be to return to the threshold of 300 percent.

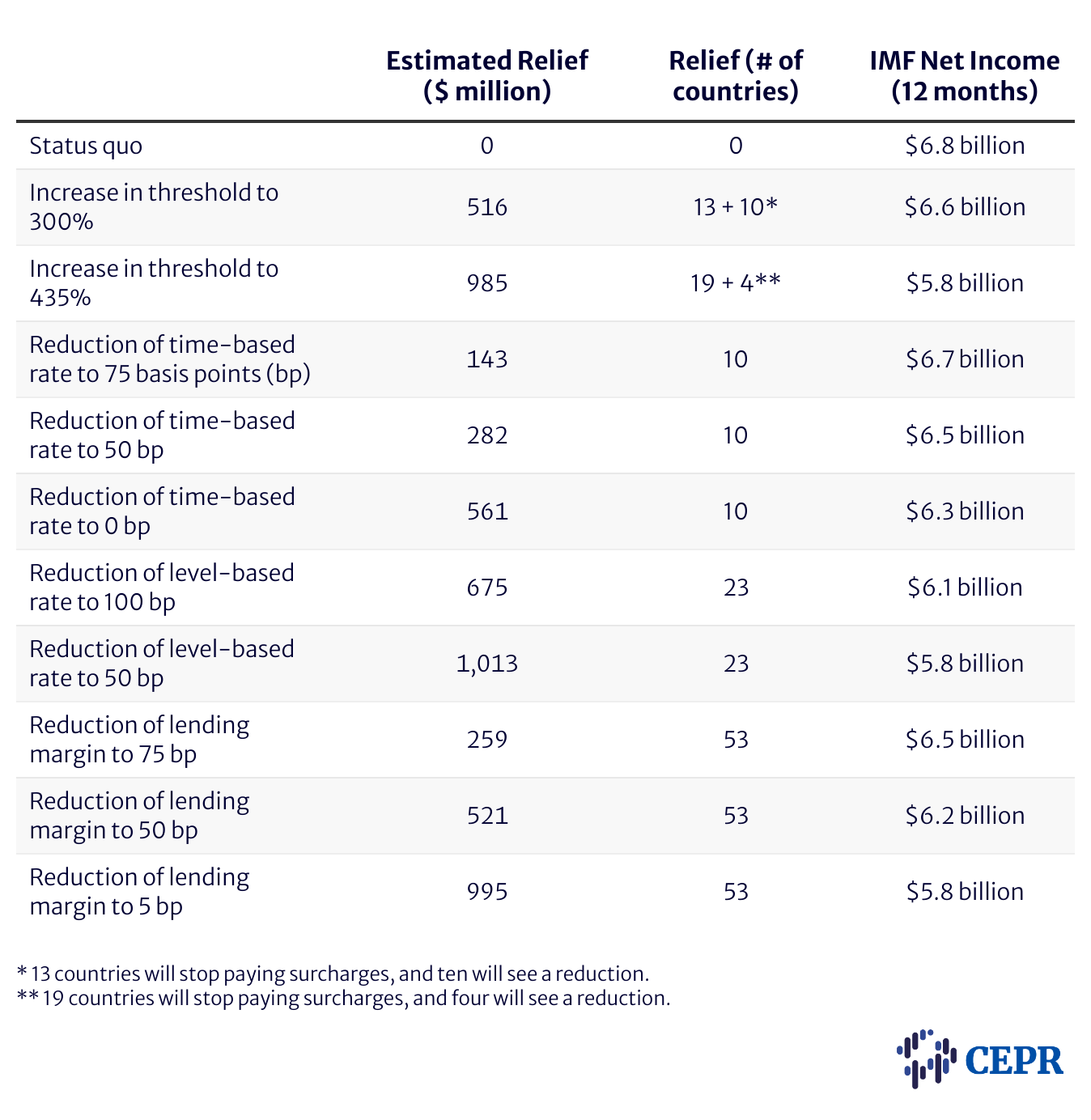

All else being equal, this increase in the threshold would mean an estimated reduction in $516 million in surcharge dues from a total of $1.9 billion over the IMF’s last four quarters and would reduce the number of countries paying surcharges from 23 to 10. This would mean complete surcharge relief for 13 countries. The 10 countries that would still have to pay surcharges would collectively see partial relief of about $446 million.

The impact of this threshold shift on the IMF’s bottom line would be approximately $516 million. With this change alone, the IMF would still be able to count on $6.3 billion in net income.

Another potential outcome could be to apply the same threshold that the IMF applies for exceptional access: 435 percent.2 Loans above this amount require the IMF to get a waiver from the Board. It would be illogical to charge extra fees for loans that are within the limit of this exceptional access threshold.

With the threshold at 435 percent, we estimate a reduction in $985 million in surcharge dues compared with the period August 2023–July 2024 and a reduction in the number of countries paying surcharges from 23 to four. With this higher threshold, the IMF would record $5.8 billion in net income.

The IMF levies two types of surcharges. Level-based surcharges of 200 basis points are levied on all outstanding GRA credit in excess of the surcharge threshold, and an additional time-based surcharge of 100 basis points is levied on outstanding GRA credit that has exceeded the threshold for more than 36 or 51 months, depending on the lending facility. Crucially, these surcharges are not a penalty for late payment — they apply even if the agreed-upon amortization schedule is being met on a timely basis.

Bloomberg reports that one of the proposals currently under discussion is to reduce the time-based rate to 75 basis points. All other variables remaining unchanged, this would have a minimal impact on countries’ surcharge dues. Surcharge obligations would only decrease by $143 million per year. This is barely more than a 7.4 percent reduction in total surcharge fees and merely a tiny dent in the IMF’s bottom line, which would decrease from $6.8 billion to $6.7 billion.

Members of the Board can safely propose a more aggressive cut. There are two reasonable proposals for a time-based surcharge. Given that countries should not be penalized if they are making their payments on a timely basis, the first proposal should be a reduction to 0 basis points. This would reduce the IMF’s bottom line from a whopping $6.8 billion to $6.2 billion.

An alternative and still reasonable reduction would be to reduce the time-based rate to 50 basis points. There is precedent for the 50 basis points proposal as it is the main rate increment the IMF has previously used in former formulations of surcharges and is the rate the IMF currently uses as a service fee. This would save countries $282 million in surcharges and would reduce the IMF’s bottom line from $6.8 billion to $6.5 billion.

This alternative would be particularly reasonable if it were accompanied by a reduction in the level-based surcharge rate that could be reduced from 200 to 50 basis points. This measure, on its own, would entail savings in foreign exchange and budget resources that would amount to $1 billion for emerging and developing countries. And it would only reduce the IMF’s bottom line from $6.8 billion to $5.8 billion.

If these two rate reductions were to be taken together — again, a time-based rate cut to 50 basis points and a level-based rate cut to 50 basis points — emerging and developing countries could secure relief totaling approximately $1.30 billion. The IMF’s bottom line would get a haircut from the record-breaking $6.8 billion to $5.5 billion.

The basic rate is the standard rate that IMF borrowers have to pay, separate from surcharges and other fees. The basic rate is composed of the variable Special Drawing Rights (SDR) interest rate, which depends on monetary policy rates in five jurisdictions (US, eurozone, Japan, UK, and China), and a lending margin. The SDR rate is currently at 3.511 percentage points or 351.1 basis points. The lending margin is currently 100 basis points. It is unlikely that the Board would want to modify the formula for the SDR rate, refer to a fraction of the SDR rate, or define a negative lending margin. It is also unlikely that the Board would define the lending margin as zero.

However, it is important to recall that in 2014 the IMF Board decided to override the formula and set a floor for the SDR interest rate at 5 basis points. At the time, the lending margin was 20 times larger than the actual SDR rate. In contrast, the average SDR rate of 2024 is 80 times higher than that of 2021. A lending margin of 5 basis points would provide relief to 53 countries for $1191 million. It would reduce the IMF’s net income from $6.8 billion to $5.6 billion.

Another point of reference can be the IMF’s previous use of 50 basis points, as explained above, both as an increment and as the current service fee. Therefore, a reasonable scenario is a reduction of the lending margin from 100 to 50 basis points. This would mean $627 million in savings of precious hard currency and budget resources for 53 emerging and developing countries currently paying the basic rate to the IMF. The impact on the IMF’s bottom line would be a marginal reduction from $6.8 billion to $6.2 billion.

Analogous to the proposal for the reduction of the time-based surcharge rate referenced by Bloomberg, we expect creditor countries to propose a reduction in the lending margin from 100 to 75 basis points. This would represent a relief of a mere $313 million for the whole of over 53 emerging and developing countries. The IMF’s net income would face a negligible reduction from $6.8 billion to $6.5 billion (see Table 1).

Table 1. Twelve-Month Impacts of Individual Measures for Surcharge Reform Under Discussion at the IMF Board

We would recommend that IMF board members take into consideration the record-breaking earnings of the IMF (see Figure 1), the fact that the target level of precautionary balances (funded by a combination of lending income, including surcharges, and investment income) was met years in advance, the debt distress that many of its borrowers are experiencing, and the need to act boldly to provide relief to 53 emerging and developing economies. It is important to act now as it is likely that another review of the surcharge policy will not take place for years.

Source: IMF Annual and Quarterly Reports

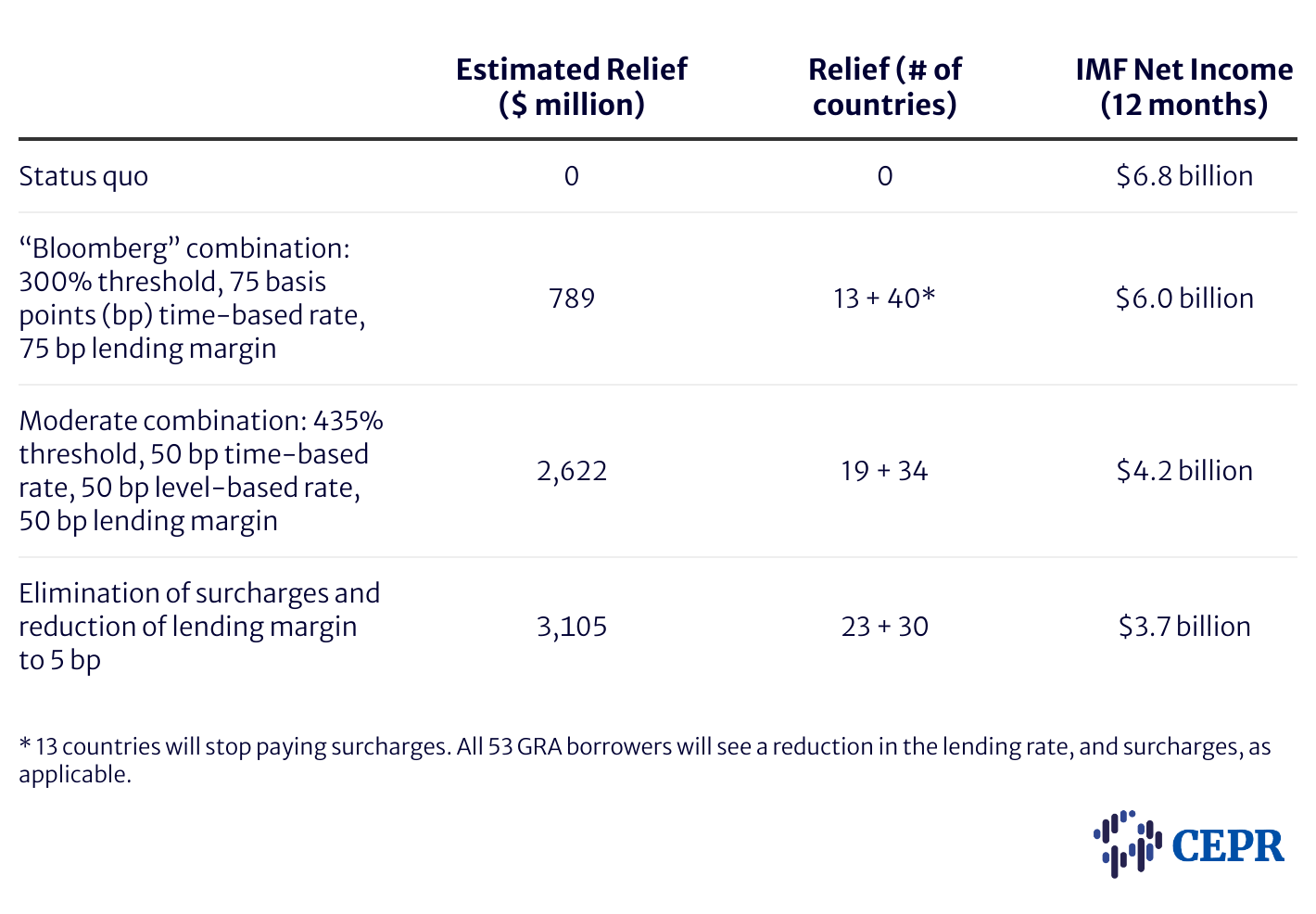

An ideal combination would be the complete elimination of surcharges and — given the drastic increase in the SDR interest rate — a reduction in the lending margin to 5 basis points. This would yield $3.1 billion in much-needed relief to 53 emerging and developing countries. The IMF’s bottom line would go back to historic levels, from $6.8 billion to a perfectly viable $3.7 billion.

We consider that, at a minimum, the combination of measures should include (1) an increase in the surcharge threshold to 435 percent of quota, (2.1) a reduction of the time-based rate to 50 basis points, (2.2) a reduction of the level-based rate to 50 basis points, and (3) a reduction of the lending margin of the basic rate to 50 basis points.

This combination would yield $2.6 billion in much-needed relief to 53 emerging and developing countries. The IMF’s bottom line — its net operating income — would decrease from $6.8 billion to a very healthy and still record-breaking $4.2 billion (see Table 2).

Surcharges are particularly unjust and harmful and should be eliminated entirely. At the same time, it is true that all countries have faced markedly increased borrowing costs, whether they meet the surcharge threshold or not. These countries would also benefit from relief. Therefore it is reasonable to invert the magnitudes of the components of the basic rate; if, for a long time — when most countries took on this debt — the SDR rate was at 5 basis points and the lending margin was at 100 basis points, now the lending margin can be 5 basis points while the SDR rate remains above 350 basis points. Even in this profoundly necessary albeit improbable scenario, the IMF’s net income would be above recent and historical averages.

If the prior combination isn’t deemed politically viable, the most effective way to reduce the burden of surcharges is through a moderate combination of an increase in the threshold to the level of the IMF’s exceptional access limits and a reduction of the surcharges’ rates and the lending margin of the base rate. This is the moment for the Executive Directors to confidently put the brakes on a burdensome policy stemming from unconvincing arguments.