October 10, 2014

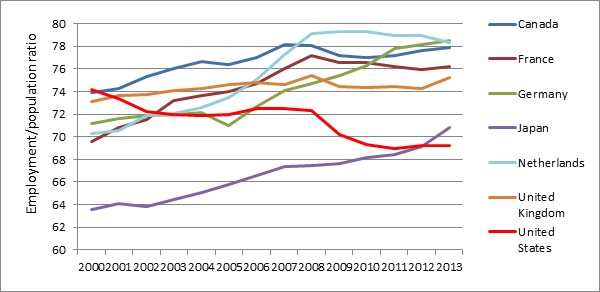

Back in 2000, a higher share of U.S. women aged 25 to 54 were employed than was the case for prime age women in six of our peers in the OECD. Newly released data from the OECD (see figure below) show that the rate has declined, in both relative and absolute terms, over the last 14 years and is now the lowest in the group, a trend clearly visible in the graph below. Even Japan, which in 2000 was more than 10 percentage points below the U.S. now has a higher share of prime age women in employment.

Economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn found a similar pattern across the OECD and point to the expansion of “family-friendly” policies in other countries as enabling women to stay in the workforce. The average length of parental leave available to workers in non-U.S. OECD countries increased from 37.2 weeks in 1990 to 57.3 in 2010, while the U.S. went from no leave to 12 weeks of unpaid leave with the passage of the federal Family and Medical Leave Act in 1993. Differences in the experiences of higher and lower-income workers are also worth noting, as the former’s employers are more likely to offer generous leave policies similar to those available in other OECD countries. Lower-income households often do not qualify for FMLA protections and, even when they do, may be unable to afford unpaid leave. A 2008 CEPR report detailed thirteen states’ more expansive family leave policies, though these are still a far cry from many other countries’ leave policies.

Data collected by the International Social Security Association on the six non-U.S. countries depicted in the graph above indicate that some work-life policies have long been available in these countries: Germany has had maternity benefits since 1952; the Netherlands has had sickness and maternity benefits since 1966; and Japan, perhaps surprisingly, has had a national health insurance program since 1938 that provides maternity and child care allowances. Countries in the European Union provide a minimum of 14 weeks of paid maternity leave, a directive that has been in place since 1992. Additionally, a number of improvements in work-life policies were enacted during the timeframe examined by Blau and Kahn. For example, Canada established maternity benefits in Quebec in 2006; France established paternity leave in 2001 and maternity insurance in 2004; Germany established long-term care benefits in 1994; the Netherlands extended maternity benefits to unemployed workers in 1998; and the UK established work and family benefits in 2005.

With dual-income households becoming not only the norm but a requirement in most cases for achieving a middle class standard of living in the U.S., addressing the decline in the share of prime age women that are employed is becoming increasingly important. A recent report by CEPR and the Center for American Progress found that “middle-class households would have substantially lower earnings today” were it not for women increasing their working hours; however, most of that increase took place between 1979 and 2000.

The lack of flexibility in the workplace may be forcing U.S. women to choose between family and work responsibilities, while “family-friendly” policies and greater control over work schedules have the potential to give men and women the ability to balance both. Striking that balance requires gender-neutral work-family policies, particularly non-transferrable “use-it or lose-it” leave policies, and continued attention in the workplace to equal employment opportunity to avoid the possibility of negative impacts on women’s wages and workplace advancement. In this regard, the federal Family and Medical Leave Act in the U.S. can serve as a model, an idea advanced in another CEPR report in its analysis of parental leave policies. Establishing such policies may be the best way to address the decline in the share of prime age women in the U.S. who are employed and give lower and middle-income families greater financial security.