Article

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

The United Nations Office of the Special Envoy for Haiti (OSE) released updated figures on the status of donor countries’ aid pledges earlier this week. The analysis reveals that just 43 percent of the $4.6 billion in pledges has been disbursed, up from 37.8 percent in June. This increase of $230 million is much larger than the observed increase in aid disbursement from March to June, when total disbursements increased by only $30 million. Also, an additional $475 million of aid money has been committed, meaning more money is now in the pipeline for Haiti. This increase is certainly a positive development, yet the overall levels of disbursement remain extremely low. The $4.6 billion in pledges was for the years 2010 and 2011, which means that donors have only a few months to fulfill their pledges.

While $1.52 billion was disbursed in 2010, this year, less than 30 percent of that—$455 million—has been disbursed. The United States, which pledged over $900 million for recovery efforts in 2010 and 2011, has disbursed just 18.8 percent of this (PDF). Of countries that pledged over $100 million dollars, only Japan has achieved 100 percent disbursement.

But it is important to go beyond the level of disbursements to see how much of this money has actually been spent on the ground and how it has supported both the Haitian public and private sectors. The following analysis shows that much of the money donors have disbursed has not actually been spent on the ground yet, that the Haitian government has not received the support it needs, and that Haitian firms have largely been bypassed in the contracting process.

Just 10 percent of funds disbursed by the Haiti Reconstruction Fund, which received nearly 20 percent of all donor pledges, have actually been spent on the ground. The Interim Haiti Recovery Commission has approved over $3 billion in projects, yet most have not even begun. Budget support for the Haitian government is set to be lower in 2011 than it was before the earthquake in 2009. Finally, only 2.4 percent of U.S. government contracts went directly to Haitian firms, while USAID relied on beltway contractors (Maryland, Virginia and DC) for over 90 percent of their contracts.

Disbursed By Donor Doesn’t Mean Spent on the Ground

The international community has set up a number of institutions that aim to centralize aid flows and projects, in particular the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC) and the Haiti Reconstruction Fund (HRF). The HRF has received roughly 20 percent of donor funds.

Our analysis of the Haiti Reconstruction Fund’s annual report revealed that despite public announcements touting a 71 percent disbursal rate at the Fund, in reality, closer to 10 percent had actually been spent on the ground, much of which was on consultant fees.

The HRF report notes that “The Trustee has transferred funds totaling US$197 million in respect of those approved projects and associated fees to the Partner Entities,” and an additional $40 million is set to be transferred. Together the $237 million is equal to 71 percent of the total funds raised. However, as the HRF notes, this money has not actually been spent on the ground, but simply transferred to their Partner Entities (the World Bank, UN and the Inter-American Development Bank – IDB). The disbursement of funds from those organizations is just $35 million, or about 10 percent of the total contributions received. The IDB, which has received $37 million in HRF funds, has yet to actually disburse any of this total.

Despite this, the HRF press release at the time listed a number of projects as “highlights of the work done so far. ” HRF manager Josef Leitmann commented to the Financial Times:

“That’s no mean feat in an environment like Haiti where there are so many obstacles and challenges to getting things done on the ground.”

Yet the projects that Leitmann refers to –though funding has been made available for them by the HRF — have not actually been undertaken. As is clear from the HRF’s own report, nowhere near $240 million has been spent “on the ground.”

The IHRC, which approves projects, but does not fund them, has green-lighted over $3 billion in projects, yet the vast majority of them remain underfunded or in the very early stages of implementation. Although not all IHRC-approved projects provided updates on disbursement rates, an analysis of the Performance and Anti-Corruption Office’s Status Update reveals that just over $100 million, or 3 percent, has been spent on 75 projects. In the critical health sector, less than 2.5 percent of the $350 million in approved projects has been spent as of June.

Additionally, the OSE found in June that close to 75 percent of bilateral recovery aid to Haiti went to international NGOs, contractors and multilateral agencies. Although this money has been disbursed to these partners there is no guarantee, or transparent data showing, that it has been spent on the ground in Haiti yet.

Aid as Accompaniment

As important as the level of disbursement is the question of where that money has gone. In June, the OSE published “Has Aid Changed? Channeling Assistance to Haiti Before and After the Earthquake,” which analyzed whether donors “have changed the way they provide their assistance in accordance with the principle of accompaniment”, which “is specifically focused on guiding international partners to transfer more resources and assets directly to Haitian public and private institutions as part of their support.”

While 2010 saw some changes in donor behavior, including increased budget support, there are signs that the change has been temporary. The June report notes:

Over 50 percent of the budget support disbursed after the earthquake arrived in the last two months (August and September 2010) of the Haitian fiscal year, more than eight months after the earthquake. According to the IMF, only 29 percent of the budget support pledged for the 2011 fiscal year has been disbursed by donors, although over half of these funds remain in the HRF and have not yet reached the government. The delayed disbursements to budget support negatively impacted the government’s ability to effectively plan activities.

Although there were some changes, the Special Envoy concludes that little has changed overall, and that “[m]ost aid is still channelled in the form of grants directly to international multilateral agencies, and non-state service providers (NGOs and private contractors).” Yet, as the Deputy Special Envoy to Haiti Paul Farmer notes, strengthening Haiti’s public institutions is a must, and the report concludes that “aid is most effective at strengthening public institutions when it is channelled through them.”

The updated numbers from the OSE reveal an increase of $40 million in budget support coming from the European Commission. Yet even after this increase, direct budget support for fiscal year 2011 remains below the amount Haiti received in 2009, before the earthquake decimated much of the government. This is especially critical as many aid agencies continue to wind down operations or fully pull out of Haiti. In many cases the Haitian government, which remains underfunded, is left to pick up the slack.

Support to the Haitian Private Sector – Spending the Development Dollar Twice

In addition to supporting the Haitian public sector, the idea of accompaniment pertains to supporting the Haitian private sector. One of the most direct ways to stimulate local production is through local procurement practices. Peace Dividend Trust (PDT) has been working in Haiti since 2009 to increase the amount of aid that enters the local economy. The Peace Dividend Marketplace is a forum that connects local businesses with development agencies, NGOs, and foreign governments. Forthcoming research from PDT shows that their database contains over 2,200 local businesses, over 600 of which are in the construction sector.

PDT describes the benefits of local procurement as “spending the development dollar twice.” Previous PDT research, predominantly focusing on Afghanistan, revealed that “only a small portion of the aid money pledged and spent in the aftermath of a disaster or conflict will actually be channeled through the host government and local economy.” PDT was instrumental in creating the “Afghanistan Compact,” in which “donors agreed to channel an increasing proportion of their assistance through the core government budget, either directly or through trust fund mechanisms. Where this was not possible, the Compact acknowledges the significance of three things: using national partners rather than international partners to implement projects; increasing procurement within Afghanistan; and using Afghan goods and services wherever feasible rather than importing goods and services.” Yet in Haiti, no such explicit policy exists.

PDT research in Afghanistan showed that “funds provided through trust fund and budget support arrangements” had the greatest local economic impact, calculated by PDT at 80 percent. This means that 80 percent of the funds enter the local economy and generate local economic impact. In comparison, funding provided to international NGOs and contractors provided just 15 percent local economic impact. Although not an exact science, it is reasonable to assume a similar breakdown in Haiti. As mentioned earlier, the OSE report in June found that some 75 percent of recovery funding went to international NGOs, contractors and multilateral agencies where the local economic impact is much lower than direct budget support.

The HRF, although much of its funds remain unspent, is an example of how trust funds can have a greater local impact than contracts with NGOs or for-profit companies. According to the HRF annual report, the Haitian government is the implementing partner for 88.4 percent of HRF funds. Based on PDT research, this will likely lead to the most significant local economic impact of aid allocation.

As was previously mentioned, over 600 of the Haitian businesses listed by PDT are in the construction sector, a key area for development projects. A forthcoming report from PDT on local procurement within the construction sector surveys local business and international organizations, and reveals that at least in the construction sector, many organizations are already doing business with Haitian firms. This is especially important because as PDT found in Afghanistan, “[i]nternational construction contracts are approximated at a 10-15% local economic impact,” an especially low rate. The forthcoming report finds that 32 of 33 international organizations surveyed had used local construction companies, but were much more likely to use larger Haitian firms. Over 60 percent of the companies PDT interviewed had fewer than 10 employees, but these firms were much less likely to have done work for an international organization.

Although PDT has found that many aid organizations are contracting with Haitian businesses, it is unclear what the economic impact is. As PDT explained in Afghanistan, the reason why international construction contracts have such a low economic impact is that “[t]he vast majority of funds are used to pay for international staff and the procurement of international materials – including capital equipment as well as inputs. These companies use a considerable amount of local labour, but since local wages are often much lower than wages paid to international staff, this figure does not represent a large portion of the overall expenditures.” Further research from PDT may shine more light on this issue.

The US and Local Procurement – Haitian Firms Remain Sidelined

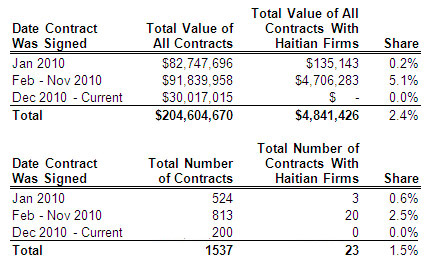

The United States, and especially USAID, have made many statements concerning local procurement and their commitment to work with Haitian companies, yet this commitment has yet to show up in their actual contracting. An updated analysis of the Federal Procurement Database System (FPDS) shows that an extremely low percentage of contracts are going to Haitian companies. As can be seen in Table I, as of September 15, 1537 contracts had been awarded for a total of $204,604,670. Of those 1537 contracts, only 23 have gone to Haitian companies, totaling just $4,841,426, or roughly 2.4 percent of the total. For every $100 dollars spent, just $2.40 has gone directly to a Haitian firm.

Table I.

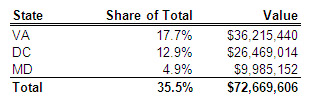

While Haitian firms have largely been left on the sidelines, Beltway contractors (from DC, Maryland and Virginia) have received 35.5 percent of the $200 million in contracts, as can be seen in Table II. We have written before about the controversial track records of two of the largest Beltway contractors, DAI and Chemonics.

Table II.

USAID has actually been one of the worst US government agencies in terms of contracting to local businesses. USAID has awarded contracts totaling $32.5 million, yet not a single contract has been awarded to a Haitian company. In addition, an astounding 93 percent of contracts awarded by USAID have gone to Beltway contractors. Although some of the companies that USAID contracts with use Haitian inputs and subcontract to Haitian firms, USAID does not publicly disclose this information making a more detailed analysis of the local economic impact impossible. As Edward Rees of Peace Dividend Trust told the AP back in December, “No one is systematically tracking how many contracts have gone to Haitian companies.”

A USAID Inspector General report on the provision of shelter determined that the way grants were made was problematic and excluded Haitian businesses:

USAID/OFDA implemented the shelter project by accepting unsolicited grant proposals issued under a waiver for competition because of the urgency of the need after the earthquake. Grants, which do not permit substantial involvement by the Agency, may not have been the best award mechanism to achieve rapid construction of cost-effective shelters meeting industry standards. If USAID/OFDA had used contracts for shelter construction, it could have prescribed the shelter design and could have given local Haitian businesses an opportunity to participate.

The IG recommended to USAID/OFDA that they “set-aside awards to local organizations for future awards for transitional shelter construction.” Although they disagreed with the IG’s recommendation, USAID/OFDA noted that they “support making subawards to local organizations,” and that “it could add a requirement that all proposals include local partners to increase the number of local organizations involved in constructing transitional shelters.”

Additionally, the report found that the largest contractors had not employed as many Haitians as originally planned. The AP reported at the time:

And an audit this fall by US AID’s Inspector General found that more than 70 percent of the funds given to the two largest U.S. contractors for a cash for work project in Haiti was spent on equipment and materials. As a result, just 8,000 Haitians a day were being hired by June, instead of the planned 25,000 a day, according to the IG.

In addition to the above analysis, USAID has provided frequent updates on their humanitarian funding in Haiti since the earthquake. An analysis of USAID factsheets shows that 50 percent of the nearly $1.2 billion in humanitarian funding was allocated to U.S. government agencies. International NGOs and contractors received over 30 percent and UN agencies 16 percent. While there is no doubt that some of this money went to Haitian businesses or NGOs as subcontractors, not a single Haitian organization is named as an “implementing partner” among the 98 activities listed.