December 17, 2010

I’m getting to this late, but the New York Times’ David Leonhardt and Mother Jones’ Kevin Drum started a discussion earlier this week on whether a social safety net –especially the availability of health insurance– could actually promote entrepreneurship in the United States.

Here’s David Leonhardt:

Guaranteeing people a decent retirement and decent health care does more than smooth out the rough edges of capitalism. Those guarantees give people the freedom to take risks. If you know that professional failure won’t leave you penniless and won’t prevent your child from receiving needed medical care, you can leave the comfort of a large corporation and take a chance on your own idea. You can take a shot at becoming the next great American entrepreneur.

And here’s a slightly skeptical Kevin Drum:

Still, I remain curious about the Leonhardt argument, which is a common one in the liberal community. Is it true? Does knowing that you have a safety net make you more likely to get up on the trapeze and try something risky and new? The analogy is wonderful, but that doesn’t make it true. Surely, though, this is a testable hypothesis? Not a provable one, of course, but one where evidence can be amassed on different fronts based on measurements of social safety nets in different times and places vs. risk-taking behavior in different times and places. Has anyone ever done this? It seems like a pretty obvious thing to try to study.

The short answer is yes, economists have looked at this issue, and the evidence generally supports the view that a safety net supports self-employment and small businesses.

Nathan Lane and I provided some indirect evidence of this in a paper we wrote for CEPR in the summer of 2009 (“An International Comparison of Small Business Employment“ (pdf)). For rich countries with roughly comparable economies, the United States consistently has among the lowest levels of self-employment and small-business employment.

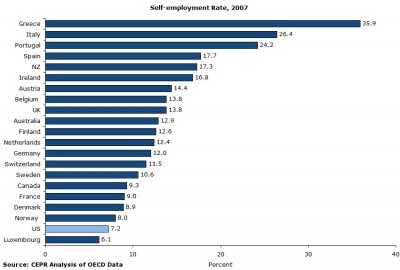

For example, using data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the United States has the lowest level of self-employment (except Luxembourg). The US data here may not be directly comparable with the data in the other countries, but even after making adjustments for this, the United States only rises to somewhere just above France and still below Sweden.

There are no internationally comparable data on economy-wide small-business employment, but the OECD does publish estimates for a large selection of broad industry groups. In those data, the United States is near the bottom when it comes to small-business employment in manufacturing (here defined as fewer than 20 employees, but the same holds for all larger cutoffs in the OECD data).

Source: Schmitt and Lane, OECD.

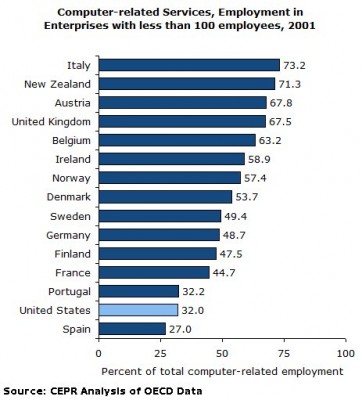

The same holds for high-tech services, too. Here are the data for “computer-related services” using a cutoff of 100 or fewer employees.

In fact, the United States is at or near the bottom of every category for which the OECD has produced internationally comparable data. (See our paper (pdf) for more details.)

Economists have also looked at the connection between health insurance and entrepreneurship more formally. Probably the best, and certainly the most recent work is by Robert Fairlie, Kanika Kapur, and Susan Gates, who have a September 2010 RAND Working Paper called “Is Employer-Based Health Insurance A Barrier To Entrepreneurship?” Their answer: yes, it sure looks that way.

They present two persuasive pieces of evidence. First, men and women are much more likely to be self-employed when their spouse has employer-provided health insurance than when their spouse does not. Many would-be entrepreneurs take advantage of their spousal coverage to cover themselves (and their children) when they start up. (Economist Alison Wellington reached a similar conclusion in an earlier paper.)

Second, Fairlie, Kapur, and Gates find that men just over age 65 –and therefore eligible for Medicare– are more likely to be self-employed than otherwise similar men just under age 65 –and therefore not yet eligible for Medicare. Medicare seems to be unleashing the entrepreneurial talents of new seniors.

Imagine what “Medicare for All” might do.

This article originally appeared on John Schmitt’s blog, No Apparent Motive.