January 11, 2013

Port-au-Prince – The origin of Haiti’s deadly cholera outbreak is not much in doubt, at least not to anybody outside the U.N. A host of scientific studies have all pointed to UN troops whose waste made it in to the largest river in Haiti as the source. While the U.N. has yet to accept responsibility, it has announced an initiative to raise funds for a $2.2 billion 10-year cholera eradication plan. At this point however, no official plan even exists, at least not publicly. Meanwhile, pressure continues to build for the U.N. to do more, and put up its own funds rather than just relying on notoriously unreliable donor pledges. The U.N. said it would chip in $23 million for the plan, a mere 1 percent of what is needed. This compares to the nearly $1.9 billion that the U.N. has spent since the earthquake on the troops that brought cholera to Haiti.

As we have previously noted, Haitian President Martelly recently added his voice to the chorus, saying that “certainly” the U.N. should take responsibility and that “[t]he U.N. itself could bring money to the table.” Grassroots pressure both within Haiti and outside has also increased. More than 25,000 have signed an online petition created by Oliver Stone calling on the U.N. to take action and secure the needed funding. And while it has been over 14 months since over 5,000 Haitians demanded reparations for those affected and for the U.N. to invest in the needed infrastructure, as of yet there has been no formal response from the U.N.

Cholera Not “Under Control”

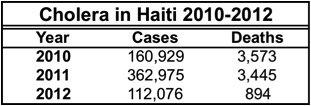

In the meantime, cholera continues to wreak havoc throughout the country. Although the number of cases and deaths has dropped this year, the epidemic still sickened over 110,000 and killed 900, making cholera more prevalent in Haiti than anywhere else in the world. Nevertheless, the Haitian Health Minister took to the radio a few days ago to talk about the “success” of the cholera response; the Prime Minister has previously declared the epidemic to be “under control”. The U.N. recently lauded the efforts of the government and humanitarian actors for managing “to contain the spread of cholera in 2012.”

But despite the statements of success, the ability to respond to the epidemic continues to decrease. From August of 2011 to August of 2012 the number of cholera treatment centers has decreased from 38 to 20, while the number of treatment units has decreased from 205 to 71. Funding to respond to the outbreak is decreasing as NGOs struggle to get donors interested in an epidemic over two years old. While funding comes in fits and starts after a hurricane or devastating storm, the response needs consistent support so as to be prepared for those emergencies rather than just a response to them.

As one health expert who asked to remain anonymous noted, while the number of cases may slow slightly next year because of the natural progression of the disease, “2013 will be even worse than 2012.” With the number of health facilities dwindling and humanitarian actors pulling out, it is likely that the mortality rate could actually increase in 2013, according to the expert.

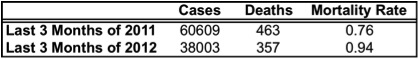

In fact, there is some evidence that this is already happening. In the last three months of 2012 while the number of cases and deaths were lower than the same months of 2011, the case fatality rate actually increased slightly. December 2012 was the first month that saw a greater number of deaths than the same month of the previous year. And the increase wasn’t small – 137 this year compared to 47 last year. The fatality rate for December was 1.2, up from 0.8 last year. While the increase over 2011 can be partially explained by the passage of Hurricane Sandy in October, it had such a large impact because of the already declining response capacity.

Additionally, in some rural areas where those who contract cholera may have to walk many hours just to reach health facilities, fatality rates continue to be far above that of the national rate. In the Grand’Anse and Sud-Est provinces the rate remains above 4 percent, for example.

While in some parts of the country, the Haitian ministry of health is actively working on the response and taking over treatment facilities, this has not yet occurred on a national scale. As humanitarian actors pull out, it will become even more imperative to transfer the response system to the ministry of health. Unfortunately, the ministry remains poorly funded and has been unable to fill in the gaps left by departing aid agencies.

According to Médecins Sans Frontières, which has played a critical role in responding to the outbreak:

The transition process is much too slow…[t]hat’s because Haitian institutions are weak, donors have not kept their promises, and the government and the international community have failed to set clear priorities.

Of the money that has been disbursed by donors, little of it has made its way to the Haitian government. For example, direct budget support to the governmentwas lower in 2011 and 2012 than in 2009, the year before the earthquake. Amazingly, the Red Cross got more money for the cholera response than the national government.