October 01, 2014

The 2011-12 Social Security payroll tax holiday ended in January 2013, which meant that the vast majority of working Americans faced a two percent cut in their take-home pay.

Compared to past payroll tax increases, this was an extraordinarily large and sudden one. For example, from 1980 to 1990 the rate was increased gradually by a total of 2.24 percentage points; in no year did the rate rise by more than 0.72 percentage points, or just over one-third of the 2013 increase. (This combines the employer and employee side tax increases. In 2013, the whole tax increase was on the employee side.)

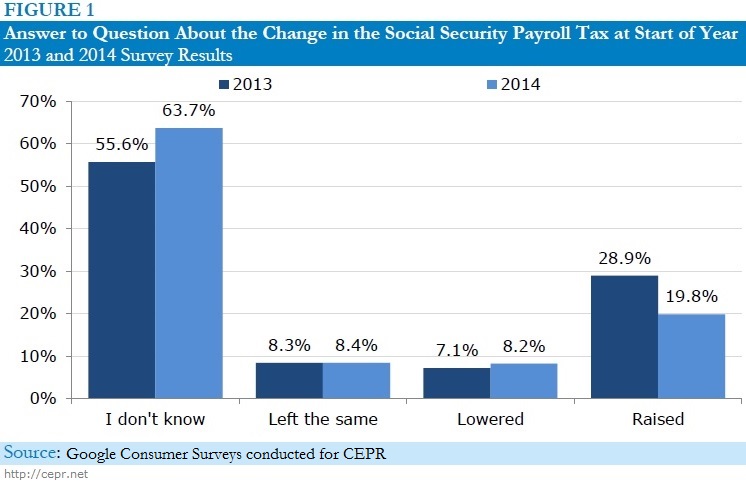

If the public were strongly opposed to tax increases, it would be expected that one as large as in 2013 would lead to considerable anger. This is why it was striking to find that most people apparently did not even notice that the payroll tax had gone up. In a 2013 Google Consumer Survey, CEPR asked whether the Social Security tax had been raised, lowered, or left the same at the beginning of the year. A majority answered that they didn’t know. Less than 3 out of 10 correctly answered that the tax had gone up.

In addition, this result likely overstates the share of the public that actually recognized the tax increase. Presumably some people answered that the tax had increased simply because they generally believe that government raises taxes. To get a sense of the size of this portion of respondents, we asked the same question in 2014. This year, almost 2-in-10 people incorrectly answered that their payroll taxes had increased at the beginning of 2014. The figure below shows the distribution of answers to the question in both years.

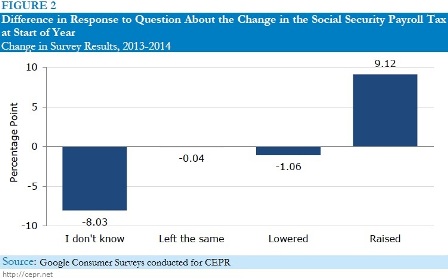

Let’s assume that the respondents who erroneously said that the tax increased in 2014 gives us a rough estimate of the number of people who believe that taxes rise regardless of the facts. Then we can estimate that the share of the public who actually noticed the tax increase would be the difference between the number who said the tax had increased in 2013 and those who said, incorrectly, that the tax had increased the following year. This figure shows the differences between the answers in the two years.

The difference between the percentage of respondents who said that the tax had increased in 2013 and those who answered similarly in 2014 was 9 percentage points. This means that less than 1 in 10 people surveyed were able to recognize an unusually large increase in the payroll tax.

This has interesting policy implications. When looking at ways to reduce Social Security’s projected funding shortfall, very few political leaders have been willing to propose any increase in the payroll tax, not even one slowly phased in over decades. For example, if a two percentage point increase in the payroll tax were phased in over twenty years, the rate would go up by only one-tenth of a percentage point per year.

These survey results suggest that the public may not be especially adverse to a modest increase in the payroll tax, since they may not even notice it. This supports the findings of other polls that indicate that most Americans favor strengthening Social Security through revenue increases, such as raising the payroll tax rate or the cap on taxable wages.

The 2013 payroll tax increase occurred in an environment in which no major political leaders were arguing against it. It was part of a bi-partisan budget agreement between the President and Congress, so both political parties had agreed to this tax increase. The public response likely would have been different if some political leaders had been openly arguing against it.

In other words, these survey results suggest that the obstacles to implementing a gradual payroll tax increase to reduce Social Security’s projected funding shortfall reside in the decisions of political leaders, and how the media choose to report them, rather than any inherent public opposition to higher taxes.

Let’s face it: The public cannot be too upset by tax increases if they don’t even notice when they take place.