February 01, 2018

President Trump’s call in the State of the Union for paid family and medical leave for workers, coming on the eve of the 25th anniversary of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), was a high point in his address to the nation. The FMLA provides unpaid leave to eligible workers at companies with 50 or more employees. A large majority of Americans across the political spectrum favor leave with pay for workers who face their own or a family member’s serious health problem, need to care for a departing or returning military service member, or need time to recover from childbirth and bond with a new baby or adopted child. The devil, as always, is in the details, and the President’s address provided no hint of these.

A national paid leave program that is universal, accessible, comprehensive, affordable, and inclusive would bring the US into the 21st century.

But is this what the administration has in mind?

The recently passed tax law provides clues into what the President may be thinking. A provision in the tax offers an incentive to companies that provide employees earning less than $72,000 a year at least two weeks of paid leave. The companies will get a credit on their taxes of between 12.5 percent and 25 percent of the cost of the leaves. The goal is to motivate employers — especially small businesses — to voluntarily provide workers with paid family and medical leave. This may work for some large employers. But because the credit is small and is not paid until the end of the year, it is much less viable for smaller businesses. The out-of-pocket expenses for employers that finance paid family and medical leaves are too large for all but the largest businesses. Moreover, this taxpayer subsidy of employer-paid leaves in the new tax law is temporary — it expires in two years, hardly enough time for a company to get a paid leave program up and running.

Starbucks, which recently extended paid parental leave to new fathers in its stores, credited the new tax law with making it possible. The company — the latest employer with deep pockets to provide or expand paid family and medical leave benefits for its employees — illustrates what is wrong with the Republican approach. Only a large and successful company can afford to take advantage of the subsidy, and few of them are likely to do so voluntarily.

While Starbucks’ expansion of its paid leave policy is a welcome development, the company’s policies also serve as a stark reminder of the two-tiered system of paid leaves provided by even the most generous employers. Starbucks’ baristas are treated much differently than its white-collar staff. Salaried employees get up to 18 weeks of paid maternity leave, while store employees get just six. New fathers in white-collar jobs get 12 weeks of paid parental leave, store employees get the six weeks the company just announced. Part-time workers employed less than 20 hours a week receive no paid time to welcome a new child. And the leave doesn’t apply to caring for a serious personal or family illness.

Unequal access to paid parental leave is the norm in the US, unlike all other modern economies. Workers who most need paid leaves are the least likely to have them. Only six percent of employees at the bottom quarter of the pay ladder have access to paid family leave, while those in the top quarter are four-times as likely to have it. Shockingly, three-quarters of even high-paid workers lack access to paid family leave to bond with a new baby or care for a seriously ill parent or spouse.

CEPR’s analysis of the Department of Labor’s 2012 Family and Medical Leave Act Survey documented employees’ need for paid family and medical leave. The study found that nearly a third of private-sector employees taking unpaid leave incur debt as result of their leave. Fully 14.2 percent of employees on unpaid leave went on public assistance, compared to 5.0 percent who received some pay during leave. One-in-four employees needing leave in the 12 months prior to the survey did not take a leave. Not being able to afford unpaid leave (49.4 percent), and the risk of job loss (18.3 percent) were the two most common reasons given for not taking the needed leave.

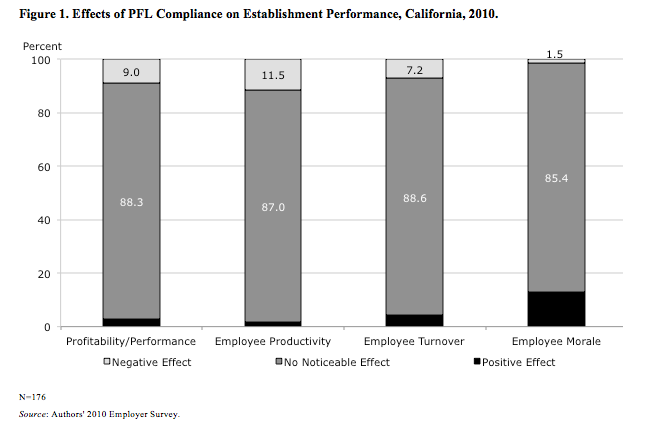

An analysis of a survey of California employers six years after implementation of the state’s landmark, first in the nation, paid family leave law found that, despite the protestations of business lobbyists, it was a non-event. While legislation was being debated before and after passage, business lobbyists denounced paid family leave as a “job killer.” They voiced concern over the high costs of covering the work of those on leave, and about potential abuse. And they claimed the burden would be especially difficult for small businesses. But these fears proved unfounded. The overwhelming majority of employers reported no effect or a positive effect on profitability/performance, employee productivity, employee turnover, and employee morale. Small businesses (fewer than 50 employees) reported more favorable results than larger employers.

State governments are pointing the way. Five states and the District of Columbia have already enacted paid family and medical leave programs. Here is how they work: employees (and in some states employers) contribute small amounts of money to create an insurance pool that allows people to draw a significant portion of their wage during family and medical leave. No employer has to pay the full cost of leaves for his or her workers and no worker has to go without pay when a new baby arrives or a medical emergency strikes.

These state programs are paving the way for a federal program that can help all families in the US Representative Rosa DeLauro and Senator Kirsten Gillibrand are sponsors of the Family and Medical Insurance Leave (FAMILY) Act. The FAMILY Act provides workers with up to 12 weeks of partial pay when they need time to recover from their own serious illness or to deal with the serious health problems of a child, parent, spouse or domestic partner; to recover from childbirth and to bond with a new baby or adopted child; or for some military caregiving and leave purposes. It enables workers to receive 66 percent of their monthly wages, up to a cap. It would cover workers in all companies, regardless of the size of the company. And finally, similar to the state programs, it would be funded by a small payroll contribution — two-tenths of 1 percent each from employees and employers. This is 80 cents a week for a worker earning $10 an hour, $1.50 a week for a typical worker.

The US is the only modern economy in which workers are not guaranteed access to paid family and medical leave. A detailed plan from President Trump for a paid family and medical leave program that encompasses all workers, is affordable and is accessible would be a truly welcome advance and one whose time — 25 years after passage of the FMLA — has finally come.