February 04, 2020

February 5th marks the 27th anniversary of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), which gave many workers access to unpaid job-protected leave to care for a new child or an illness of the worker or a relative. FMLA remains an important step forward in workers’ rights because it covers more than half of the workforce while improving maternal health and reducing infant mortality. However, many workers are still unprotected by the law and require employer beneficence to take unpaid leave. Further, the US remains the only high-income country of 34 in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) not to offer paid leave to at least one parent of a newborn child. For new families in the US, that leads to disastrous financial effects, as around 7 percent of bankruptcies are caused by childbirth.

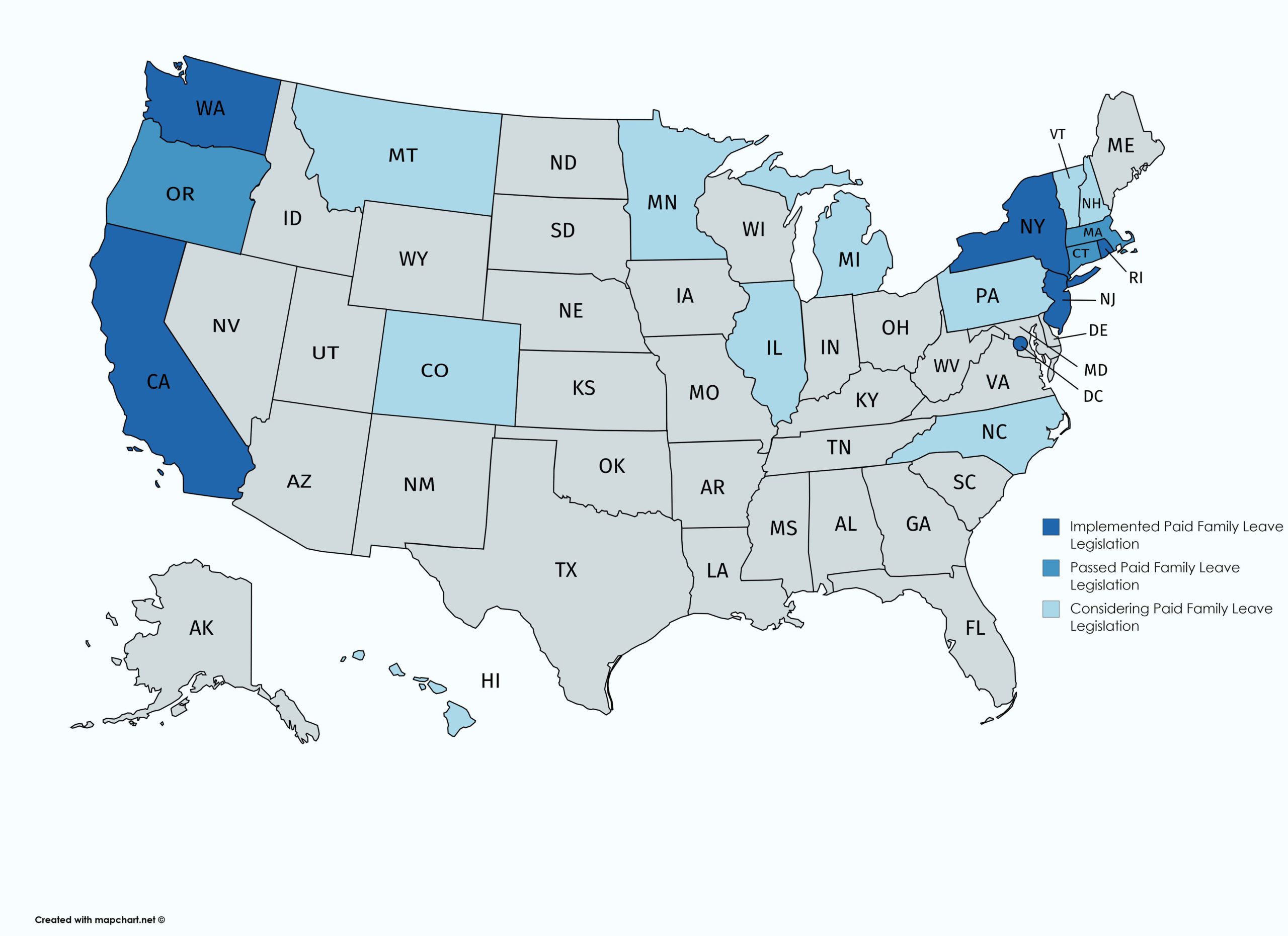

The good news is that the issue of family leave is at the top of the policy agenda. In the 27 years since the FMLA’s passage, attempts to pass a national paid leave program remained stuck in Congress. Action on paid leave moved to the states, and five states — California, New Jersey, Rhode Island, New York, Washington State, plus D.C. — have stepped up to pass and implement paid family leave policies that cover over 27 million people, according to the advocacy group Family Values at Work. An additional 6.6 million people will be covered by three states — Massachusetts, Oregon, and Connecticut — that have already passed paid leave legislation but the laws have yet to go into effect (see Figure 1). The momentum for paid family and medical leave that is building in the states is now spilling over to a national campaign that launched in late 2019 to win a national paid leave program. On the national level, members of Congress from both parties have sponsored the FAMILY Act which would provide workers with 12 weeks of paid leave, replacing 66 percent of the worker’s income while on leave. Advocates are focusing their energies on improving this extremely promising piece of legislation and working towards passing it.

Improving the FMLA

Many workers are excluded from the protections of the FMLA, especially those on part-time schedules. FMLA does not cover workers at firms with less than 50 employees within a 75-mile radius, workers who were not with a firm for a year, or did not work at least 1,250 hours (average of 24 hours per week) in the previous 12 months. These restrictions disproportionately hit workers in low-income occupations. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that, as of 2018, while 95 percent of the highest 10 percent of earners have access to unpaid family leave, more than one-fifth of workers in the bottom 10 percent of wage earners do not have access.

Low-income workers, such as fast food workers, are more likely to be excluded from FMLA because their employers use franchising and contracting schemes that get around the 50-employee requirement, or workers get too few work hours to qualify. Moreover, because many low-wage earners have jobs with high turnover rates, they end up not working for a company long enough to get FMLA. Further, low-income workers are less likely to have other paid time off they can use in the absence of paid leave. While 77 percent of all private sector workers have some paid vacation, only 39 percent of the bottom 10 percent of earners do because their employer doesn’t offer it or because they are unable to accrue vacation time. This means that using other paid time off to supplement one’s income during a short leave is impossible for many low-income workers. These requirements also, almost by definition, exclude temporary and seasonal workers who have difficulty meeting the hours requirement of the FMLA.

Learning What Works from State Paid Leave Programs

In 2002, California became the first state to pass a paid family leave policy. Since then, eight states and the District of Columbia have followed by passing their own plans, with three of those states not yet having implemented those plans. These programs have been beneficial for households of all incomes.

First, paid leave plans help keep new parents out of poverty. A recent study from the Social Service Review looking at data from 2000–2013, showed that California’s modest paid leave program reduced the risk of mothers of 1-year-olds falling into poverty by 10.2 percent and increased their household’s income by 4.1 percent after birth. This finding is consistent with other research that showed that paid leave helped reduce poverty for new parents in 18 OECD countries from 1978–2008.

Second, paid leave policies also benefit women of all incomes. Paid leave is associated with making it more likely that women stay attached to the labor force. A study of California’s paid leave program showed that after implementation of paid family leave, new mothers were 18 percentage points more likely to be working one year after birth and saw their hours at work increase by 18 percent two years after birth. Simply put, there is broad consensus that paid family leave helps women keep their jobs if they would like to do so.

However, there are issues that states are still working to address. For example, wage replacement for low-income workers remains a big issue because rent and other fixed costs don’t go down simply because a worker is on paid leave. Losing a significant fraction of one’s income for a week or longer makes paid leave unaffordable for these workers. Policymakers could look to Oregon which will guarantee 100 percent of the worker’s wage up to 65 percent of the statewide average when that state’s law goes into effect in 2023 to ensure low-income workers can take advantage of paid leave.

Lawmakers are also working on making the definition of family more inclusive and representative of the range of American families — multi-generational families, blended families and, in the case of the LGBTQ communities, chosen families. Some states, like New Jersey and Oregon, include provisions that allow covered individuals to take leave to care for someone with whom they have a close association. This makes it possible for people in non-nuclear family structures to have access to paid leave to welcome a new child or to deal with their own serious illness or that of an individual with whom they have a close family or family-like relationship.

Further, strengthening job protection remains an issue with current leave proposals.. Some state programs and federal proposals, including the FAMILY Act do not include access to job protection for all workers on paid leave. Workers are only guaranteed that they can return to their jobs if they qualify for FMLA, which as we noted, a substantial number of workers, mostly low-income, do not. Policymakers at both the federal and state levels should follow the lead of states like New York and Rhode Island that have expanded job protection beyond FMLA.

Gender equity is another concern in paid leave. States that have implemented paid leave programs have generally allowed non-birth parents of all genders to take leave. However, despite this, men still take substantially less leave than women. This can serve to entrench gender norms in harmful ways by pushing women out of the workplace. One solution that has been tried in other countries is to reserve time specifically for the non-birth parent that cannot be transferred to the other parent in two-parent households. Another solution is to increase the wage replacement rate so non-birth parents can afford to take time off. When these strategies were implemented alongside each other in the Canadian province of Quebec, leave taking among fathers increased 250 percent, which in turn led to equalizing the division of home and market labor with fathers increasing the amount of time performing home labor and mothers increasing their time doing market labor.

Lastly, all state plans, except for DC, have tenure or earnings requirements that disallow workers who recently started jobs or earned very little in the previous year from accessing paid family leave. The FAMILY Act has earnings requirements that use the same work requirements as Social Security Disability Insurance program. So while the vast majority of workers would qualify for paid leave, it could be exclusionary to working people of very low incomes, or who are trying to take leave for a second or third time because they don’t get credited for working during the months they are on leave. Such requirements are not necessary. According to the World Policy Center, about half of OECD countries do not have any tenure or contribution requirements for receiving parental leave. Its research does not find any association between tenure or contribution requirements and solvency of the paid leave system, or “labor force participation, unemployment, or growth.”

The Next Move for Advocates

Conservatives in Congress also recognize the need of working families for paid family leave. Most recently, Senators Cassidy and Sinema have introduced an alternative to the FAMILY Act that they claim provides paid family leave. However, this legislation — which only addresses parental leave — is not actually a paid leave program. Essentially, the Cassidy-Sinema bill offers a loan to new parents to cover the cost of leave for 12 weeks, which they must then pay back through a cut to their Child Tax Credit (CTC) benefits over 10 to 15 years. A loan is not the same as paid family leave because it does not provide any net new benefit to families. Beyond that, the proposal is flawed in many ways. Losing part of the Child Tax Credit seriously damages low-income families’ ability to adequately provide for their children and make ends meet. This would also disincentivize workers from taking leave because many will not be able to afford to lose money over the next few years. This is especially true for the lowest income households because they are most likely not to receive the full CTC benefit in the first place. Further, covering only “new parents” is radically more exclusionary than any bill passed in the United States to this point in history. The FMLA and all nine state-level bills allow workers to take leave to care for their own health condition or a family member’s health condition, such as caring for sick child or an aging parent with a serious health condition. Ignoring these leave claims is serious because 75 percent of FMLA claims are to care for someone other than a new child. Cassidy-Sinema simply is not a workable option for American families.

The FAMILY Act, on the other hand, represents the best chance to pass a national paid family leave program that provides new benefits to families without asking them to sacrifice their financial futures. It has bipartisan support in Congress and will allow families to take paid leave to welcome a new born, foster or adopted child, or to care for themselves or a family member with a serious medical concern. Amendments to the FAMILY Act to be considered by Congress will allow for a higher wage replacement for low-income workers, a more inclusive definition of family, and expansion of job protection to more workers. Advocates are working to ensure that these amendments are in the final version of the bill, which they hope will become law by 2023. In the meantime, advocates are working to improve existing state programs and to pass additional paid leave laws. California and New Jersey are working on expanding their existing programs while 10 states — Colorado, Hawaii, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Vermont — are all considering legislation to create new programs. Continuing the momentum on the state level will expand coverage to millions of people and will drive momentum for passage of the FAMILY Act.