A Washington Post article on Uber’s IPO told readers that Uber drivers earned $21 an hour and linked to a study that came out of Stanford as the source. The study actually reports that $21 is the gross pay before deducting driving expenses such as gas and depreciation. This is very clear in the study.

It notes (page 42) the difference where it suggests a net measure might be more appropriate for the issue it is assessing (gender differences in earnings):

“Suppose drivers average 25 cents per mile in costs other than insurance – Uber covers drivers’ insurance costs while driving. A typical Uber driver covers about 20 miles in one hour. The driver earns approximately $15.80 net of Uber’s current 25% average share of driver gross earnings.”

Arguably 25 cents is too low a figure. The federal government uses 58 cents as it per mileage compensation charge. Since Uber covers insurance for the driver, let’s say 40 cents per mile is closer to the mark. That would translate into expenses of $8 an hour, lowering the pay net of expense to $12.80 an hour, almost 40 percent less than the figure in the Post article.

A Washington Post article on Uber’s IPO told readers that Uber drivers earned $21 an hour and linked to a study that came out of Stanford as the source. The study actually reports that $21 is the gross pay before deducting driving expenses such as gas and depreciation. This is very clear in the study.

It notes (page 42) the difference where it suggests a net measure might be more appropriate for the issue it is assessing (gender differences in earnings):

“Suppose drivers average 25 cents per mile in costs other than insurance – Uber covers drivers’ insurance costs while driving. A typical Uber driver covers about 20 miles in one hour. The driver earns approximately $15.80 net of Uber’s current 25% average share of driver gross earnings.”

Arguably 25 cents is too low a figure. The federal government uses 58 cents as it per mileage compensation charge. Since Uber covers insurance for the driver, let’s say 40 cents per mile is closer to the mark. That would translate into expenses of $8 an hour, lowering the pay net of expense to $12.80 an hour, almost 40 percent less than the figure in the Post article.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Last week Krugman devoted a column to dismissing the Democrats septuagenarians (Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders) as not being prepared to deal with the presidency in today’s political environment. Part of his indictment of Sanders was an unwillingness to compromise, most notably on health care reform.

As Krugman put it:

“For Sanders, then, it seems to be single-payer or bust. And what that would mean, with very high likelihood, is … bust.”

To back up this position, Krugman notes Sanders’ unwillingness to support a bill that would improve the Affordable Care Act.

Actually, it is wrong to claim that Sanders has seen single-payer as an all or nothing proposition. He voted for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, when his vote was essential for the bill’s passage.

Sanders was also a supporter of Bill Clinton’s health care reform bill that never even made it to the floor in Congress. He has often told a story of apologizing to Clinton for his conduct on the bill.

According to Sanders, Clinton said, “what do you mean Bernie, you were with me all the way.”

To which Sanders replied, “That’s exactly it. I should have been burning you in effigy on the steps of the capital.” [These are my memory, not necessarily verbatim.]

Sanders’ point was that he should have insisted on a more drastic reform, which would have made Clinton’s plans seem moderate in comparison. In this context, it is entirely reasonable for Sanders to push for a more extensive reform, like universal Medicare, even if he is prepared to sign on to a more moderate package involving reforms to the ACA if the time comes for that.

Given Sanders history on health care, it is wrong to say that he has adopted an all or nothing approach. He has repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to compromise to extend and improve coverage.

Addendum

Krugman also questioned whether Sanders could work across party lines. He has made common cause with Republicans on occasion in the past, with important results. A noteworthy example was in 2010, when he became the lead Senate proponent of a proposal originally advanced by Ron Paul in the House, to audit the Fed. The result of this effort was an amendment to the Dodd-Frank financial reform act which required the Fed to disclose the beneficiaries and the terms of the more than $10 trillion in emergency loans it made during the financial crisis. The amendment was approved by the Senate on a vote of 96-0.

Last week Krugman devoted a column to dismissing the Democrats septuagenarians (Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders) as not being prepared to deal with the presidency in today’s political environment. Part of his indictment of Sanders was an unwillingness to compromise, most notably on health care reform.

As Krugman put it:

“For Sanders, then, it seems to be single-payer or bust. And what that would mean, with very high likelihood, is … bust.”

To back up this position, Krugman notes Sanders’ unwillingness to support a bill that would improve the Affordable Care Act.

Actually, it is wrong to claim that Sanders has seen single-payer as an all or nothing proposition. He voted for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, when his vote was essential for the bill’s passage.

Sanders was also a supporter of Bill Clinton’s health care reform bill that never even made it to the floor in Congress. He has often told a story of apologizing to Clinton for his conduct on the bill.

According to Sanders, Clinton said, “what do you mean Bernie, you were with me all the way.”

To which Sanders replied, “That’s exactly it. I should have been burning you in effigy on the steps of the capital.” [These are my memory, not necessarily verbatim.]

Sanders’ point was that he should have insisted on a more drastic reform, which would have made Clinton’s plans seem moderate in comparison. In this context, it is entirely reasonable for Sanders to push for a more extensive reform, like universal Medicare, even if he is prepared to sign on to a more moderate package involving reforms to the ACA if the time comes for that.

Given Sanders history on health care, it is wrong to say that he has adopted an all or nothing approach. He has repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to compromise to extend and improve coverage.

Addendum

Krugman also questioned whether Sanders could work across party lines. He has made common cause with Republicans on occasion in the past, with important results. A noteworthy example was in 2010, when he became the lead Senate proponent of a proposal originally advanced by Ron Paul in the House, to audit the Fed. The result of this effort was an amendment to the Dodd-Frank financial reform act which required the Fed to disclose the beneficiaries and the terms of the more than $10 trillion in emergency loans it made during the financial crisis. The amendment was approved by the Senate on a vote of 96-0.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The United States International Trade Commission’s (USITC) analysis of Trump’s new NAFTA projected modest gains, entirely due to a reduction of uncertainty associated with its rules on digital commerce. (It makes it harder to regulate Facebook and Google.) The gains the USITC attributed to reduced uncertainty from this fairly limited segment of the economy were extraordinary, but they raise the obvious question about the cost of uncertainty in other areas.

For example, Donald Trump is now tweeting threats to substantially expand his trade war with China, raising a wide range of tariffs from 10 percent to 25 percent. If tariffs against any country can be raised or lowered by presidential whim, then it has to create a substantial amount of economic uncertainty. It would be interesting to see how the USITC would assess the impact of this uncertainty on the economy. It would almost certainly have to be an order magnitude larger than any reductions in uncertainty in the digital economy associated with the new NAFTA.

The United States International Trade Commission’s (USITC) analysis of Trump’s new NAFTA projected modest gains, entirely due to a reduction of uncertainty associated with its rules on digital commerce. (It makes it harder to regulate Facebook and Google.) The gains the USITC attributed to reduced uncertainty from this fairly limited segment of the economy were extraordinary, but they raise the obvious question about the cost of uncertainty in other areas.

For example, Donald Trump is now tweeting threats to substantially expand his trade war with China, raising a wide range of tariffs from 10 percent to 25 percent. If tariffs against any country can be raised or lowered by presidential whim, then it has to create a substantial amount of economic uncertainty. It would be interesting to see how the USITC would assess the impact of this uncertainty on the economy. It would almost certainly have to be an order magnitude larger than any reductions in uncertainty in the digital economy associated with the new NAFTA.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That might be helpful to that small group of Washington Post readers who don’t know how large $2 trillion is over the course of a decade. It is also a bit more than 3.3 percent of projected federal spending over this period and 28 percent of projected military spending. But I’m sure everyone knew that.

That might be helpful to that small group of Washington Post readers who don’t know how large $2 trillion is over the course of a decade. It is also a bit more than 3.3 percent of projected federal spending over this period and 28 percent of projected military spending. But I’m sure everyone knew that.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what the Washington Post tells us. It notes the sharp slowdown in China’s population growth and then tells readers:

“China’s population is forecast to peak at 1.45 billion as early as 2027, then slump for several decades. By 2050, about one-third of the population will be over the age of 65, and the number of working-age people is forecast to fall precipitously. Who will power the economy? Who will look after the elderly? Who will pay the taxes to fund their pensions?”

One might think that with a population of more than 1 billion people it would not be that hard to find someone to pay taxes. More importantly, China has been seeing rapid increases in productivity and living standards, which means that even if workers have to pay higher taxes, they will still enjoy higher living standards.

To see this point, suppose real wages rise by 4.0 percent annually (much slower than they have been) for the next three decades. By 2050, real wages will be more than 220 percent higher than they are today. Suppose payroll taxes are increased by 20 percentage points to cover the cost of a larger relative population of retirees. In that case, real wages will still be almost 160 percent higher than they are today. What exactly is the problem?

It is also worth noting that as China gets wealthier and technology improves, people now considered elderly are likely to be in much better health and more productive than they are today. This means they will need less care (fewer robots?) and may still be making substantial contributions to society.

That’s what the Washington Post tells us. It notes the sharp slowdown in China’s population growth and then tells readers:

“China’s population is forecast to peak at 1.45 billion as early as 2027, then slump for several decades. By 2050, about one-third of the population will be over the age of 65, and the number of working-age people is forecast to fall precipitously. Who will power the economy? Who will look after the elderly? Who will pay the taxes to fund their pensions?”

One might think that with a population of more than 1 billion people it would not be that hard to find someone to pay taxes. More importantly, China has been seeing rapid increases in productivity and living standards, which means that even if workers have to pay higher taxes, they will still enjoy higher living standards.

To see this point, suppose real wages rise by 4.0 percent annually (much slower than they have been) for the next three decades. By 2050, real wages will be more than 220 percent higher than they are today. Suppose payroll taxes are increased by 20 percentage points to cover the cost of a larger relative population of retirees. In that case, real wages will still be almost 160 percent higher than they are today. What exactly is the problem?

It is also worth noting that as China gets wealthier and technology improves, people now considered elderly are likely to be in much better health and more productive than they are today. This means they will need less care (fewer robots?) and may still be making substantial contributions to society.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

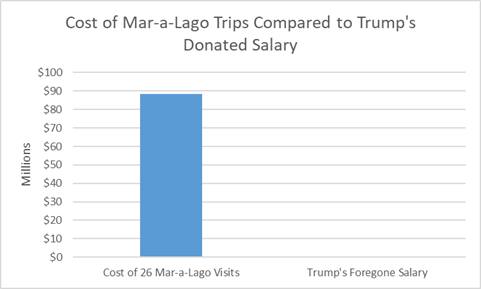

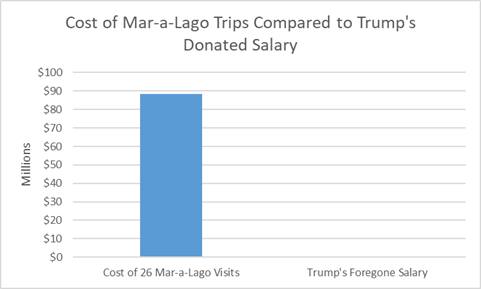

Donald Trump has made a big show of saying that because he is such a rich guy, he will donate back his presidential salary of $400,000 a year to the government. He regularly tells us which department or agency is the lucky beneficiary of his quarterly compensation.

Unfortunately, he feels no compunction about imposing extraordinary travel and security costs on the government by spending frequent weekends at his Mar-a-Lago resort or other Trump properties. This expense substantially exceeds the $400,000 that the government gets from him donating his salary, as shown in the figure below.

Source: Government Accountability Office and author’s calculations.

The chart relies on a GAO study that calculated that four Trump visits cost the government $13.6 million in extra expenses, or $3.4 million per weekend. The calculation in the graph assumes that he makes 26 trips a year, one every other week.

Donald Trump has made a big show of saying that because he is such a rich guy, he will donate back his presidential salary of $400,000 a year to the government. He regularly tells us which department or agency is the lucky beneficiary of his quarterly compensation.

Unfortunately, he feels no compunction about imposing extraordinary travel and security costs on the government by spending frequent weekends at his Mar-a-Lago resort or other Trump properties. This expense substantially exceeds the $400,000 that the government gets from him donating his salary, as shown in the figure below.

Source: Government Accountability Office and author’s calculations.

The chart relies on a GAO study that calculated that four Trump visits cost the government $13.6 million in extra expenses, or $3.4 million per weekend. The calculation in the graph assumes that he makes 26 trips a year, one every other week.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I suppose it’s hard for people in Washington to get data from the Washington-based International Monetary Fund, otherwise, they would not tell people things like China is the world’s second-largest economy, after the United States. Using purchasing power parity data, which is what most economists would view as the best measure for international comparisons, China’s GDP exceeded the U.S. GDP in 2015. It is now more than 25 percent larger.

I suppose it’s hard for people in Washington to get data from the Washington-based International Monetary Fund, otherwise, they would not tell people things like China is the world’s second-largest economy, after the United States. Using purchasing power parity data, which is what most economists would view as the best measure for international comparisons, China’s GDP exceeded the U.S. GDP in 2015. It is now more than 25 percent larger.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that productivity increased at a 3.6 percent annual rate and is now up 2.4 percent over the last year. This is a big improvement from its 1.3 percent average growth rate since 2005.

This is very good news, if it proves to be real and is sustained. It would mean that we can have more rapid improvements in living standards and have more resources for things like a Green New Deal and Medicare for All. But folks should probably hold the celebration, for now, it is very possible that this figure is a fluke since productivity data are subject to large revisions and are extremely erratic. (Arguing for the fluke story, self-employment was reported as dropping at more than a 7.0 percent annual rate in the first quarter. That’s possible, but not very likely. Fewer self-employed means fewer hours, and therefore higher productivity.)

Needless to say, the Trumpers were quick to take credit. The Wall Street Journal told readers:

“The recent gains could be a sign that an uptick in investment following tax-law changes passed in 2017 means businesses are spending on the technology and tools necessary to increase output. Some firms have turned to automation—from factory machines to shelf-scanning robots—to ramp up output while growing hours or payrolls more slowly.”

The piece then quotes Kevin Hassett, the head of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers:

“The machines people bought last year, they are turning them on this year.”

This story doesn’t make any sense since there was no tax cut induced investment boom in 2018. Investment in the first quarter of 2019 was 4.8 percent higher than in the first quarter of 2018. That is pretty much average growth and certainly not an investment boom.

There were many previous periods with much more rapid investment growth and no corresponding uptick in productivity. For example, investment grew 8.0 percent from the third quarter of 2013 to the third quarter of 2014. It grew 12.9 percent from the first quarter of 2011 to the first quarter of 2012. In neither case was there any notable uptick in productivity growth.

To see a one percentage point increase in the rate of productivity growth, we would need a jump in investment in the neighborhood of 30 percent. The Hassett story is simply not plausible on its face. The article should have made this fact clear to readers.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that productivity increased at a 3.6 percent annual rate and is now up 2.4 percent over the last year. This is a big improvement from its 1.3 percent average growth rate since 2005.

This is very good news, if it proves to be real and is sustained. It would mean that we can have more rapid improvements in living standards and have more resources for things like a Green New Deal and Medicare for All. But folks should probably hold the celebration, for now, it is very possible that this figure is a fluke since productivity data are subject to large revisions and are extremely erratic. (Arguing for the fluke story, self-employment was reported as dropping at more than a 7.0 percent annual rate in the first quarter. That’s possible, but not very likely. Fewer self-employed means fewer hours, and therefore higher productivity.)

Needless to say, the Trumpers were quick to take credit. The Wall Street Journal told readers:

“The recent gains could be a sign that an uptick in investment following tax-law changes passed in 2017 means businesses are spending on the technology and tools necessary to increase output. Some firms have turned to automation—from factory machines to shelf-scanning robots—to ramp up output while growing hours or payrolls more slowly.”

The piece then quotes Kevin Hassett, the head of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers:

“The machines people bought last year, they are turning them on this year.”

This story doesn’t make any sense since there was no tax cut induced investment boom in 2018. Investment in the first quarter of 2019 was 4.8 percent higher than in the first quarter of 2018. That is pretty much average growth and certainly not an investment boom.

There were many previous periods with much more rapid investment growth and no corresponding uptick in productivity. For example, investment grew 8.0 percent from the third quarter of 2013 to the third quarter of 2014. It grew 12.9 percent from the first quarter of 2011 to the first quarter of 2012. In neither case was there any notable uptick in productivity growth.

To see a one percentage point increase in the rate of productivity growth, we would need a jump in investment in the neighborhood of 30 percent. The Hassett story is simply not plausible on its face. The article should have made this fact clear to readers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times had a piece describing the quality control issues that Boeing seems to be having at its plant in South Carolina. It would have been worth mentioning that Boeing moved operations from Seattle, where it has an experienced unionized workforce, to South Carolina to take advantage of lower-paid non-union labor. This could have something to do with its quality control problems.

Addendum

The NYT did a very good story last month on the South Carolina plant that pointed out the decision to go with a less experienced non-union workforce.

The New York Times had a piece describing the quality control issues that Boeing seems to be having at its plant in South Carolina. It would have been worth mentioning that Boeing moved operations from Seattle, where it has an experienced unionized workforce, to South Carolina to take advantage of lower-paid non-union labor. This could have something to do with its quality control problems.

Addendum

The NYT did a very good story last month on the South Carolina plant that pointed out the decision to go with a less experienced non-union workforce.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión