It’s not clear how the paper made these determinations, but it does assert them to be true in the second paragraph of an article on the Trump administration’s plans to reduce the rights of federal employees:

“The administration describes Trump’s new rules, issued in May, as an effort to streamline a bloated bureaucracy and improve accountability within the federal workforce of 2.1 million.”

While it is certainly possible that the Trump administration is motivated by a desire to make government more efficient, given its willingness to grant no-bid contracts to politically connected companies, government efficiency does not seem to be a priority for the Trump administration. A plausible alternative that the Post seems to rule out with this assertion is that Trump is attacking a group of workers that he sees as political enemies.

It’s not clear how the paper made these determinations, but it does assert them to be true in the second paragraph of an article on the Trump administration’s plans to reduce the rights of federal employees:

“The administration describes Trump’s new rules, issued in May, as an effort to streamline a bloated bureaucracy and improve accountability within the federal workforce of 2.1 million.”

While it is certainly possible that the Trump administration is motivated by a desire to make government more efficient, given its willingness to grant no-bid contracts to politically connected companies, government efficiency does not seem to be a priority for the Trump administration. A plausible alternative that the Post seems to rule out with this assertion is that Trump is attacking a group of workers that he sees as political enemies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Any newspaper can hire reporters, but The New York Times hires mind readers. Yes, they are at it again. In an article on Trump’s demand that other NATO countries increase their military spending to 2.0 percent of GDP the NYT tells readers;

“Mr. Trump, who appears to have a special animus toward Germany, believes that Berlin has developed a vibrant social system and thriving export-driven economy unfairly and on the back of the United States, by not spending enough on defense.”

It’s so great that we have the NYT to tell us that Trump really has such incredibly absurd beliefs. The idea that Germany’s economy would somehow have suffered horribly if it had spent an additional 1.0 percent of GDP on the military is pretty crazy, especially since it has suffered from a serious lack of demand for the last decade.

This doesn’t mean that military spending would be the best use of Germany’s resources. But it’s very hard to make a case that additional spending, even if it were entirely wasteful from a social and economic standpoint, would have devastated Germany’s economy. In fact, it probably would have led to somewhat stronger growth and surely would have benefitted the other EU countries that are Germany’s largest trading partners.

Any newspaper can hire reporters, but The New York Times hires mind readers. Yes, they are at it again. In an article on Trump’s demand that other NATO countries increase their military spending to 2.0 percent of GDP the NYT tells readers;

“Mr. Trump, who appears to have a special animus toward Germany, believes that Berlin has developed a vibrant social system and thriving export-driven economy unfairly and on the back of the United States, by not spending enough on defense.”

It’s so great that we have the NYT to tell us that Trump really has such incredibly absurd beliefs. The idea that Germany’s economy would somehow have suffered horribly if it had spent an additional 1.0 percent of GDP on the military is pretty crazy, especially since it has suffered from a serious lack of demand for the last decade.

This doesn’t mean that military spending would be the best use of Germany’s resources. But it’s very hard to make a case that additional spending, even if it were entirely wasteful from a social and economic standpoint, would have devastated Germany’s economy. In fact, it probably would have led to somewhat stronger growth and surely would have benefitted the other EU countries that are Germany’s largest trading partners.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The second fact appeared in a NYT article reporting on how nursing homes are frequently understaffed; the first did not. As many doctors angrily told me after reading a column I did on the protections that inflate doctors’ pay, nursing assistants save lives.

Yes, we pay lots of money for health care in this country, more than twice as much as the average for other wealthy countries. Unfortunately, we don’t have better outcomes to justify this spending. A big part of this story is how much we pay our doctors and how little we pay less politically powerful workers in the health care industry. (Yes, inflated drug and medical equipment prices and a cesspool insurance industry are also big parts of the story, all discussed in Rigged [it’s free].)

The second fact appeared in a NYT article reporting on how nursing homes are frequently understaffed; the first did not. As many doctors angrily told me after reading a column I did on the protections that inflate doctors’ pay, nursing assistants save lives.

Yes, we pay lots of money for health care in this country, more than twice as much as the average for other wealthy countries. Unfortunately, we don’t have better outcomes to justify this spending. A big part of this story is how much we pay our doctors and how little we pay less politically powerful workers in the health care industry. (Yes, inflated drug and medical equipment prices and a cesspool insurance industry are also big parts of the story, all discussed in Rigged [it’s free].)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The top of the hour lead into Morning Edition (sorry, no link) told listeners that hiring will be down for June because employers can’t find workers. Of course, employers who understand basic economics can find workers: they just raise pay to pull them away from competitors.

We aren’t seeing any large-scale increases in pay despite near-record profit shares. This suggests that either employers really are not short of workers or that they are too incompetent to understand the basics of the market.

The top of the hour lead into Morning Edition (sorry, no link) told listeners that hiring will be down for June because employers can’t find workers. Of course, employers who understand basic economics can find workers: they just raise pay to pull them away from competitors.

We aren’t seeing any large-scale increases in pay despite near-record profit shares. This suggests that either employers really are not short of workers or that they are too incompetent to understand the basics of the market.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Like the Supreme Court, the Fed has considerable independence from day-to-day politics. It has seven governors who are appointed by the president and approved by the Senate. They can serve 14 year terms, although most do not stay for the full period.

The Open Market Committee that sets interest rate policy also includes the twelve district bank presidents. Five of these twelve bank presidents have a vote at any point in time, although all twelve take part in the discussion. The bank presidents are appointed through a somewhat opaque process that has historically been dominated by the financial industry, although this process was opened up somewhat during Janet Yellen’s tenure as Fed chair.

This process insulates the Fed from the whims of the president and other political figures. However, there is nothing inappropriate about the president or any other elected official commenting on Fed policy, as The New York Times implies in this piece.

Given the close ties of the bank presidents, and often the governors, to the financial industry, a Fed that is considered off limits for political debate is likely to be overly responsive to the concerns of the financial industry. This is likely to mean, for example, excessive concern over inflation and inadequate attention to the full employment part of the Fed’s mandate. It is understandable that the financial industry would like to keep the public unaware of the importance of the Fed’s actions, but the public as a whole does not share this interest.

Like the Supreme Court, the Fed has considerable independence from day-to-day politics. It has seven governors who are appointed by the president and approved by the Senate. They can serve 14 year terms, although most do not stay for the full period.

The Open Market Committee that sets interest rate policy also includes the twelve district bank presidents. Five of these twelve bank presidents have a vote at any point in time, although all twelve take part in the discussion. The bank presidents are appointed through a somewhat opaque process that has historically been dominated by the financial industry, although this process was opened up somewhat during Janet Yellen’s tenure as Fed chair.

This process insulates the Fed from the whims of the president and other political figures. However, there is nothing inappropriate about the president or any other elected official commenting on Fed policy, as The New York Times implies in this piece.

Given the close ties of the bank presidents, and often the governors, to the financial industry, a Fed that is considered off limits for political debate is likely to be overly responsive to the concerns of the financial industry. This is likely to mean, for example, excessive concern over inflation and inadequate attention to the full employment part of the Fed’s mandate. It is understandable that the financial industry would like to keep the public unaware of the importance of the Fed’s actions, but the public as a whole does not share this interest.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

With Donald Trump’s trade war with China heating up I thought I should bring in Mr. Arithmetic to clarify the situation. Trump apparently thinks that he holds all the cards in this one because the US imports much more than it exports to China.

As I pointed out previously, China has other weapons. For example, it can just stop respecting US patents and copyrights altogether, sending items all over the world that don’t include any royalty payments or licensing fees. This could reduce the price of patented drugs by 90 percent or more and make all of Microsoft’s software free.

But even ignoring the other weapons that China has in a trade war, the idea that the country can’t get by without the US market doesn’t fit the data. At the most basic level, China exported a bit more than $500 billion in goods and services to the United States last year. This comes to a bit more than 4.0 percent of its GDP, measured on a dollar exchange rate basis.

As many analysts have noted, much of the value of these exports is not actually valued-added in China. For example, the full value of an iPhone produced in China will be counted as an export to the United States even though most of the value comes from software developed in the United States and parts imported from other countries. Perhaps 40 percent or more of the trade deficit reflects value-added from other countries. (On the flip side, many of the imports from other countries include value-added from Chinese products.)

But let’s ignore this issue. Suppose Donald Trump’s get-tough trade policies reduce our imports from China by 50 percent, a huge reduction. This would come to roughly 2.0 percent of China’s GDP. Will this have China screaming “uncle?”

Probably not. As Mr. Arithmetic points out, China’s trade surplus fell by 4.4 percentage points of GDP from 2008 to 2009, yet its economy still grew by more than 9.0 percent that year and by more than 10.0 percent the next year. While all of China’s annual data should be viewed with some skepticism, few doubt the basic story. China managed to get through the recession without a major hit to its growth.

Of course, that drop in exports was due to an unexpected economic crisis, this one would be due to a politically motivated trade war. Mr. Arithmetic does not expect China to be giving in any time soon.

With Donald Trump’s trade war with China heating up I thought I should bring in Mr. Arithmetic to clarify the situation. Trump apparently thinks that he holds all the cards in this one because the US imports much more than it exports to China.

As I pointed out previously, China has other weapons. For example, it can just stop respecting US patents and copyrights altogether, sending items all over the world that don’t include any royalty payments or licensing fees. This could reduce the price of patented drugs by 90 percent or more and make all of Microsoft’s software free.

But even ignoring the other weapons that China has in a trade war, the idea that the country can’t get by without the US market doesn’t fit the data. At the most basic level, China exported a bit more than $500 billion in goods and services to the United States last year. This comes to a bit more than 4.0 percent of its GDP, measured on a dollar exchange rate basis.

As many analysts have noted, much of the value of these exports is not actually valued-added in China. For example, the full value of an iPhone produced in China will be counted as an export to the United States even though most of the value comes from software developed in the United States and parts imported from other countries. Perhaps 40 percent or more of the trade deficit reflects value-added from other countries. (On the flip side, many of the imports from other countries include value-added from Chinese products.)

But let’s ignore this issue. Suppose Donald Trump’s get-tough trade policies reduce our imports from China by 50 percent, a huge reduction. This would come to roughly 2.0 percent of China’s GDP. Will this have China screaming “uncle?”

Probably not. As Mr. Arithmetic points out, China’s trade surplus fell by 4.4 percentage points of GDP from 2008 to 2009, yet its economy still grew by more than 9.0 percent that year and by more than 10.0 percent the next year. While all of China’s annual data should be viewed with some skepticism, few doubt the basic story. China managed to get through the recession without a major hit to its growth.

Of course, that drop in exports was due to an unexpected economic crisis, this one would be due to a politically motivated trade war. Mr. Arithmetic does not expect China to be giving in any time soon.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s the implication of this CNBC piece that claims that hiring is down because businesses can’t find qualified workers. If this is really the problem, then the solution, as everyone learns in intro economics, is to raise wages. For some reason, CEOs apparently can’t seem to figure this one out, since wage growth remains very modest in spite of this alleged shortage of qualified workers.

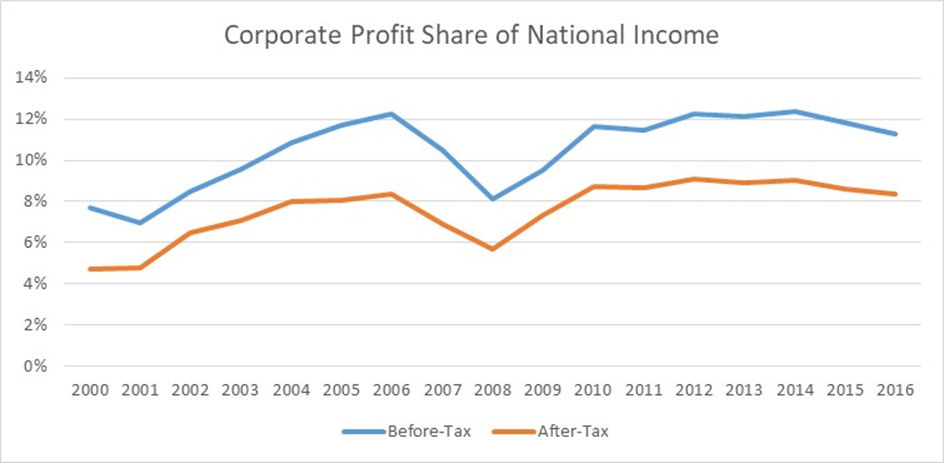

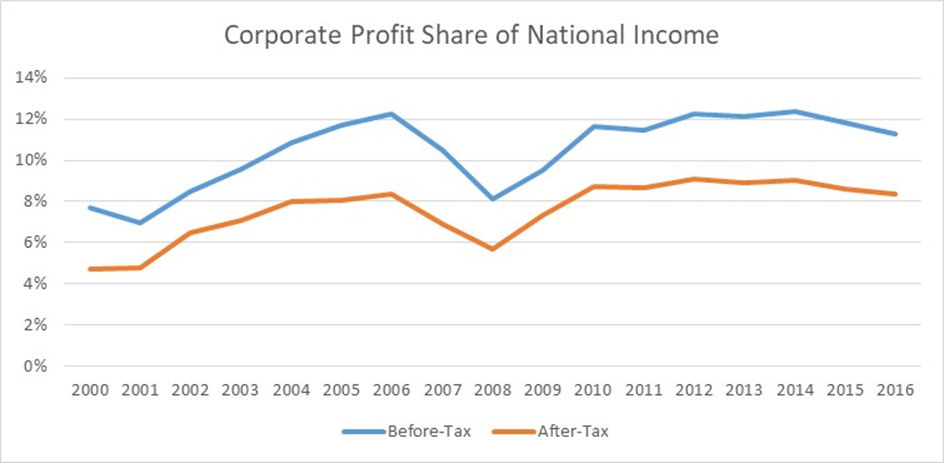

Businesses should be well-positioned to absorb higher wages since their profits have soared over the last two decades. In the years from 1980 to 2000, the beneficiaries of upward redistribution were higher paid workers like CEOs, Wall Street-types, and highly paid professionals like doctors and dentists. Since 2000, there has been a substantial shift from wages to profits, as the after-tax profit share of national income has nearly doubled, as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

The profit shares include one-third of the foreign profits of US corporations based on new research showing that this is really just profit shifting to evade taxes. If after-tax profit shares were back at their 2000 level, it would imply another $600 billion a year in wage income or almost $4,000 per worker in additional wages.

That’s the implication of this CNBC piece that claims that hiring is down because businesses can’t find qualified workers. If this is really the problem, then the solution, as everyone learns in intro economics, is to raise wages. For some reason, CEOs apparently can’t seem to figure this one out, since wage growth remains very modest in spite of this alleged shortage of qualified workers.

Businesses should be well-positioned to absorb higher wages since their profits have soared over the last two decades. In the years from 1980 to 2000, the beneficiaries of upward redistribution were higher paid workers like CEOs, Wall Street-types, and highly paid professionals like doctors and dentists. Since 2000, there has been a substantial shift from wages to profits, as the after-tax profit share of national income has nearly doubled, as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

The profit shares include one-third of the foreign profits of US corporations based on new research showing that this is really just profit shifting to evade taxes. If after-tax profit shares were back at their 2000 level, it would imply another $600 billion a year in wage income or almost $4,000 per worker in additional wages.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

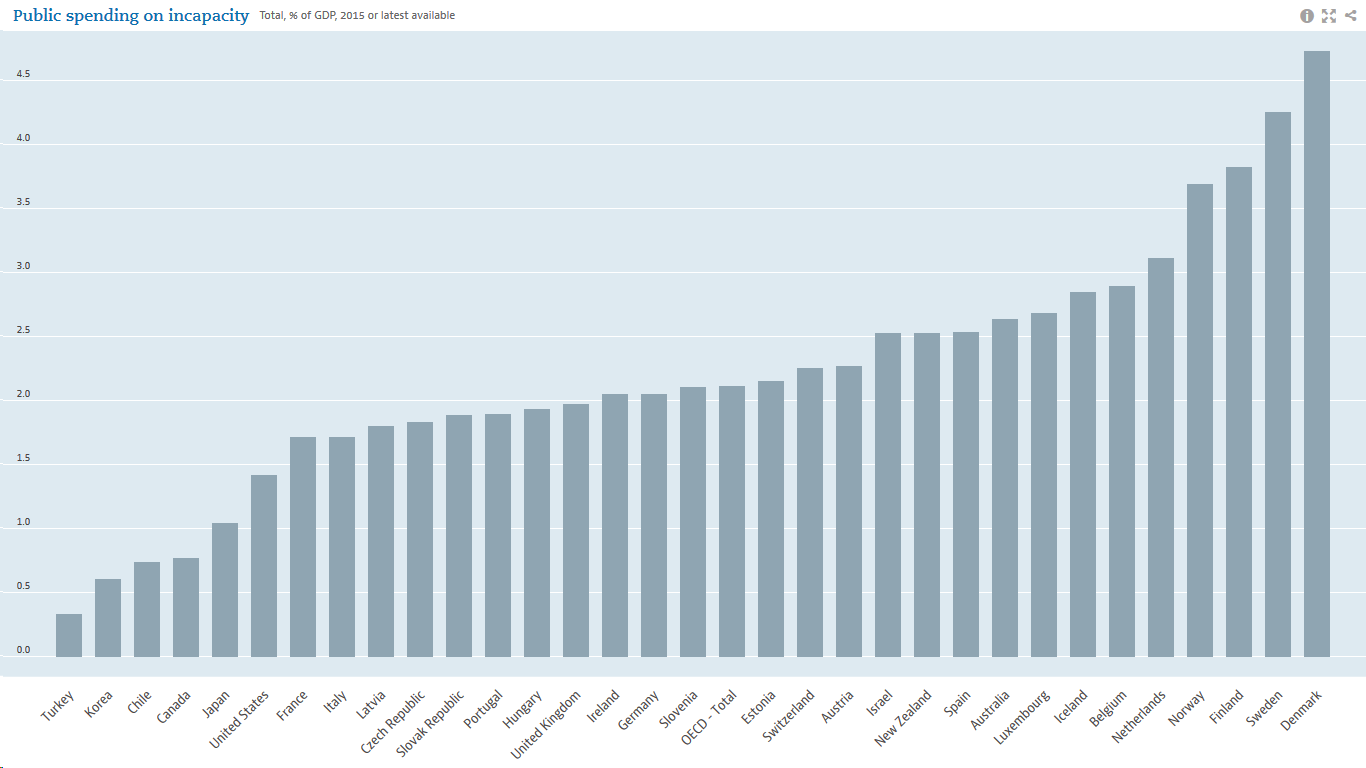

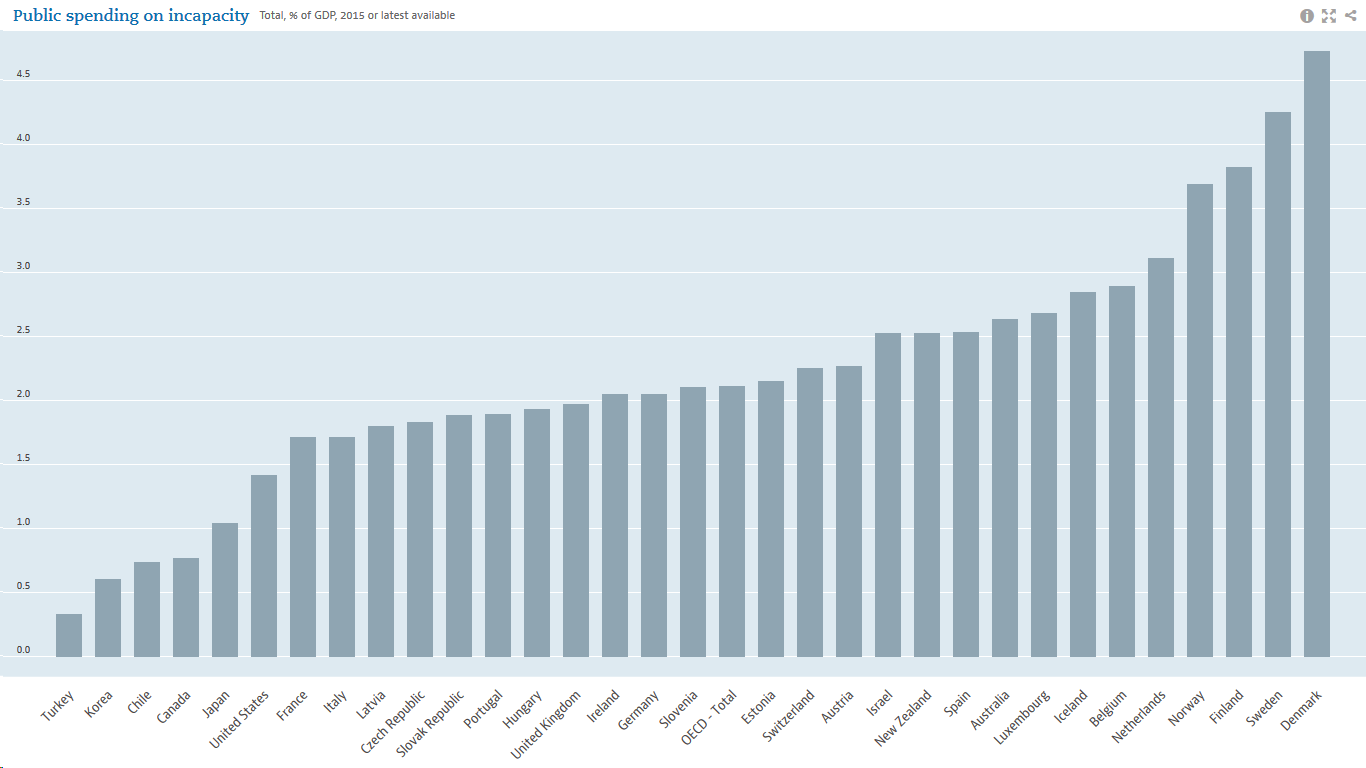

The paper owned by the man who got incredibly rich by avoiding state and local sales taxes is upset because workers are getting Social Security disability payments that average less than $1,300 a month. Since the US has one of the least generous disability programs of any wealthy country, this might seem like a strange concern. Here’s the picture from the OECD.

Source: OECD.

Of course the Post is also a paper that gets hysterical over the prospect that truck drivers will get pay increases. In short, these are folks who practice crude class war. They are okay with some crumbs for the poor, but anything that is good for ordinary workers means giving up money that could be in the pockets of the Bezoses of the world.

The paper owned by the man who got incredibly rich by avoiding state and local sales taxes is upset because workers are getting Social Security disability payments that average less than $1,300 a month. Since the US has one of the least generous disability programs of any wealthy country, this might seem like a strange concern. Here’s the picture from the OECD.

Source: OECD.

Of course the Post is also a paper that gets hysterical over the prospect that truck drivers will get pay increases. In short, these are folks who practice crude class war. They are okay with some crumbs for the poor, but anything that is good for ordinary workers means giving up money that could be in the pockets of the Bezoses of the world.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is common practice for people who completely missed the housing bubble to warn about another impending debt crisis which will sink the economy when it bursts. In this vein, we have a New York Times editorial telling us about the dangerous increase in credit card debt.

The piece tells readers:

“And now rates are now rising at time when household debt reached a record $13.21 trillion in the first quarter. Household debt service payments as a percentage of disposable income hit 5.9 percent in the first quarter, according to the Federal Reserve, a figure not reached since just before the Great Recession. Average credit card debt per borrower is about $5,700 and growing at a rate of 4.7 percent while wages are growing at about 3 percent. That can’t continue forever.”

Since they had the Fed’s data on debt burdens in front of them, they should have known the full picture, which is below.

Are you scared?

The piece also includes several other silly comparisons, starting with the comparison of the growth in average household debt to the growth in the average hourly wage. The czar of apples-to-apples insists they use average household income, which in nominal terms is growing at roughly the same rate. The editorial also repeatedly compares wealth to the 2007 bubble peaks. Surprise! We haven’t recovered.

The basis of the piece is the bad news that when the Fed raises interest rates it will mean higher interest payments on credit card debt. I am happy to have the NYT as an ally in the battle against unnecessary interest rate hikes, but the burden on credit card debt hardly tops the charts as a reason. Suppose interest rates rise 2.0 percentage points (a huge increase) on $1 trillion in credit card debt. That comes to $20 billion a year or about $150 a year per household. That’s not altogether trivial, but not a concern that keeps me awake at night.

It would be a much greater concern if Fed rate hikes kept 2–3 million people from working and lowered the wages on 30 or 40 million low- and moderate-wage workers by reducing their bargaining power. There is some value in keeping your eye on the ball and actually knowing something about the topics on which you write.

It is common practice for people who completely missed the housing bubble to warn about another impending debt crisis which will sink the economy when it bursts. In this vein, we have a New York Times editorial telling us about the dangerous increase in credit card debt.

The piece tells readers:

“And now rates are now rising at time when household debt reached a record $13.21 trillion in the first quarter. Household debt service payments as a percentage of disposable income hit 5.9 percent in the first quarter, according to the Federal Reserve, a figure not reached since just before the Great Recession. Average credit card debt per borrower is about $5,700 and growing at a rate of 4.7 percent while wages are growing at about 3 percent. That can’t continue forever.”

Since they had the Fed’s data on debt burdens in front of them, they should have known the full picture, which is below.

Are you scared?

The piece also includes several other silly comparisons, starting with the comparison of the growth in average household debt to the growth in the average hourly wage. The czar of apples-to-apples insists they use average household income, which in nominal terms is growing at roughly the same rate. The editorial also repeatedly compares wealth to the 2007 bubble peaks. Surprise! We haven’t recovered.

The basis of the piece is the bad news that when the Fed raises interest rates it will mean higher interest payments on credit card debt. I am happy to have the NYT as an ally in the battle against unnecessary interest rate hikes, but the burden on credit card debt hardly tops the charts as a reason. Suppose interest rates rise 2.0 percentage points (a huge increase) on $1 trillion in credit card debt. That comes to $20 billion a year or about $150 a year per household. That’s not altogether trivial, but not a concern that keeps me awake at night.

It would be a much greater concern if Fed rate hikes kept 2–3 million people from working and lowered the wages on 30 or 40 million low- and moderate-wage workers by reducing their bargaining power. There is some value in keeping your eye on the ball and actually knowing something about the topics on which you write.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Bloomberg doesn’t seem quite as scared as the Washington Post, which worries that if truckers earn $60,000 a year it would sink the economy. But it also seems really disturbed that employers can’t get more drivers without paying them more. This one is, in some ways, even more over the top than the Post piece. It wants to blame the government.

The story here is that there are restrictions on hours, which used to be tracked using paper records but now are verified electronically. This makes cheating more difficult.

“Under the old regime, a driver making 40 cents a mile might drive 750 miles in 15 hours, averaging 50 miles an hour and making $300. His paperwork would claim 11 hours at 68 mph. Now, however, his time is electronically tracked and the 11-hour limit is strictly enforced. At 50 mph, he makes only $220.”

So, in the good old days, a driver putting in 15 hours a day pulled down $300, or $20 an hour. If we converted this into an hourly wage, with a 50 percent overtime premium after 8 hours, this comes to $16.21 an hour. In this story, the hourly pay actually rises somewhat to $22 an hour because of the evil regulations, but because the worker is putting in 27 percent fewer hours, her daily pay falls.

In any case, it is striking that no one seems to think that higher pay might be a good way to solve this shortage. I guess no one believes in market solutions at Bloomberg.

Bloomberg doesn’t seem quite as scared as the Washington Post, which worries that if truckers earn $60,000 a year it would sink the economy. But it also seems really disturbed that employers can’t get more drivers without paying them more. This one is, in some ways, even more over the top than the Post piece. It wants to blame the government.

The story here is that there are restrictions on hours, which used to be tracked using paper records but now are verified electronically. This makes cheating more difficult.

“Under the old regime, a driver making 40 cents a mile might drive 750 miles in 15 hours, averaging 50 miles an hour and making $300. His paperwork would claim 11 hours at 68 mph. Now, however, his time is electronically tracked and the 11-hour limit is strictly enforced. At 50 mph, he makes only $220.”

So, in the good old days, a driver putting in 15 hours a day pulled down $300, or $20 an hour. If we converted this into an hourly wage, with a 50 percent overtime premium after 8 hours, this comes to $16.21 an hour. In this story, the hourly pay actually rises somewhat to $22 an hour because of the evil regulations, but because the worker is putting in 27 percent fewer hours, her daily pay falls.

In any case, it is striking that no one seems to think that higher pay might be a good way to solve this shortage. I guess no one believes in market solutions at Bloomberg.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión