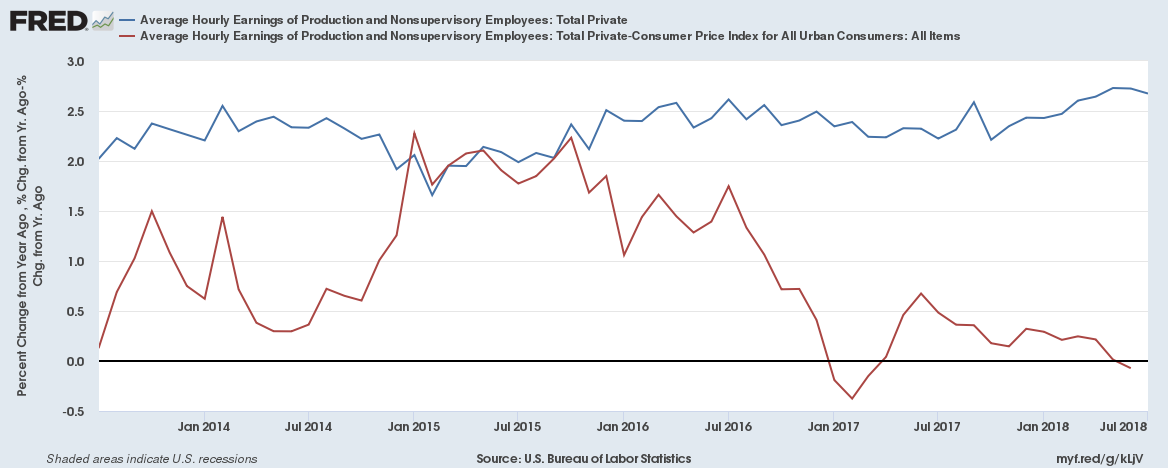

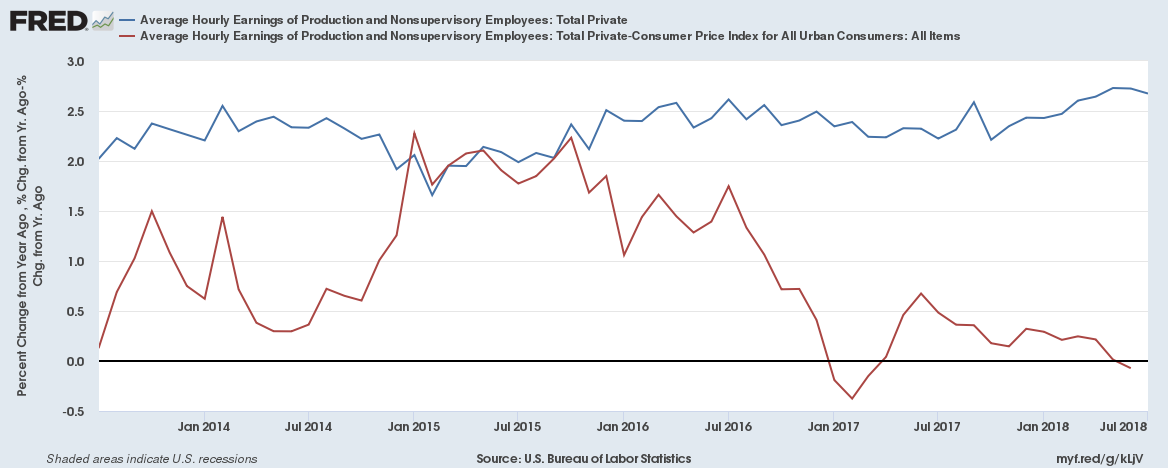

When I saw the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Employment Cost Index (ECI) numbers for the second quarter this morning, I sent a note to some friends joking about how wage growth is skyrocketing, in the sense that it isn’t. The report showed compensation rose 0.6 percent in the second quarter, this is actually a modest slowing from prior quarters.

As a practical matter, the numbers are erratic enough and the changes are small enough, that I wouldn’t necessarily argue that wage growth has slowed based on the new ECI data, but the key point is that it sure does not look like it is accelerating. Here’s picture over the last decade.

Employment Cost Index: Total Compensation

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Given what the data showed I was surprised to find a tweet from Donald Trump announcing “worker pay rate hits highest level since 2008.” It turns out this was actually the headline of a CNBC piece touting the 2.8 percent year over year growth shown in the ECI.

While Donald Trump’s confusion with the data is hardly surprising (we know he has trouble with numbers), the CNBC piece is more than a bit off the mark. First of all, it would be useful if it could distinguish rates of growth from levels. Wages and compensation are virtually always rising, which means they set new highs every month and quarter.

The headline should have indicated that this was the fastest rate of increase since 2008. Also, this was not just a problem of a confused headline writer, the first sentence of the piece tells readers:

“Compensation for workers rose to a nearly 10-year high in the second quarter as inflation pressures continued to percolate in the U.S. economy.”

Interestingly, the very next sentence gives the new data showing the slowdown in compensation growth to 0.6 percent in the quarter, although it never points out this is a slowing, instead highlighting the increase in the twelve-month growth rate to 2.8 percent, even as the new data actually goes in the opposite direction.

It also would have been useful to note that even this twelve-month rate of compensation growth does not imply any increase in workers’ real pay, as inflation over this period was also 2.9 percent. In short, this tweet from Donald Trump, like most of his tweets, didn’t make much sense, but at least, in this case, he could blame the error on someone else.

When I saw the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Employment Cost Index (ECI) numbers for the second quarter this morning, I sent a note to some friends joking about how wage growth is skyrocketing, in the sense that it isn’t. The report showed compensation rose 0.6 percent in the second quarter, this is actually a modest slowing from prior quarters.

As a practical matter, the numbers are erratic enough and the changes are small enough, that I wouldn’t necessarily argue that wage growth has slowed based on the new ECI data, but the key point is that it sure does not look like it is accelerating. Here’s picture over the last decade.

Employment Cost Index: Total Compensation

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Given what the data showed I was surprised to find a tweet from Donald Trump announcing “worker pay rate hits highest level since 2008.” It turns out this was actually the headline of a CNBC piece touting the 2.8 percent year over year growth shown in the ECI.

While Donald Trump’s confusion with the data is hardly surprising (we know he has trouble with numbers), the CNBC piece is more than a bit off the mark. First of all, it would be useful if it could distinguish rates of growth from levels. Wages and compensation are virtually always rising, which means they set new highs every month and quarter.

The headline should have indicated that this was the fastest rate of increase since 2008. Also, this was not just a problem of a confused headline writer, the first sentence of the piece tells readers:

“Compensation for workers rose to a nearly 10-year high in the second quarter as inflation pressures continued to percolate in the U.S. economy.”

Interestingly, the very next sentence gives the new data showing the slowdown in compensation growth to 0.6 percent in the quarter, although it never points out this is a slowing, instead highlighting the increase in the twelve-month growth rate to 2.8 percent, even as the new data actually goes in the opposite direction.

It also would have been useful to note that even this twelve-month rate of compensation growth does not imply any increase in workers’ real pay, as inflation over this period was also 2.9 percent. In short, this tweet from Donald Trump, like most of his tweets, didn’t make much sense, but at least, in this case, he could blame the error on someone else.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I’m beginning to feel like the mouthpiece for the complacency lobby, but we continue to see baseless articles in prominent places telling us that another financial crisis is imminent. The latest entry comes from Steven Pearlstein at the Washington Post, warning us that “The junk debt that tanked the economy? It’s back in a big way.”

The villain in this story is collateralized loan obligations (CLO). These are securities that put together a variety of loans and then are sold off in tranches. The tranches are ranked with the more senior ones getting the first claim to payments and least senior ones getting the last claim. This way a pool of risky loans can be used to create senior tranches with top investment grade ratings. The least senior tranches will be very risky and carry junk ratings but will offer a high rate of interest.

Pearlstein warns that the growth in CLOs has been explosive.

“Because the market seems to have an insatiable appetite for CLOs, leveraged lending and CLO issuance through the first half of the year are already up 38 percent over last year’s near-record levels.”

Sounds really scary, but how much is 38 percent above last year’s levels? Pearlstein never gives us a number, but a little digging tells us that the CLO market is just over $1 trillion. So how worried should we be?

Let’s call in Mr. Arithmetic. Suppose that 40 percent of these CLOs go bad, an extremely high percentage. That would be $400 billion in CLOs that could not be paid off in full. Of course, most people would still be getting their payments, since most of the loans in a CLO would likely still be paid. Let’s assume a loss rate of 40 percent on this $400 billion, a very high loss rate. That translates into $160 billion in losses.

Is this another financial crisis? We have a GDP of $20 trillion, making these losses equal to 0.8 percent of GDP. Arguably, our total wealth of close to $100 trillion is the better denominator, putting the losses at 0.16 percent of total wealth. Are you scared yet?

The story of the financial crisis was one of loans that were directly linked to a seriously over-valued asset that was widely held (housing). When the housing market collapsed, the loan supporting the market also collapsed, creating a downward spiral where falling house prices led to greater default rates, which also undermined the market for home purchases, further depressing prices.

The collapse in housing led to both a huge plunge in construction of 5 percent of GDP ($1 trillion annually in today’s economy) and a plunge in housing wealth driven consumption of almost 3.0 percent of GDP ($600 billion in today’s economy). That is what tanked the economy as it is not easy to find a way to replace lost demand equal to 8.0 percentage points of GDP.

This is hugely different than Pearlstein’s absurd story about CLOs crashing the economy in 2008. Of course, it doesn’t mean that we should not be worried about this risky loans. It is likely that lenders are making big bucks selling tranches to people who do not understand the risk. This is not a way to promote economic growth. This rip-off finance is a pure waste to the economy and diverts resources from productive uses. But it will not crash the economy.

I’m beginning to feel like the mouthpiece for the complacency lobby, but we continue to see baseless articles in prominent places telling us that another financial crisis is imminent. The latest entry comes from Steven Pearlstein at the Washington Post, warning us that “The junk debt that tanked the economy? It’s back in a big way.”

The villain in this story is collateralized loan obligations (CLO). These are securities that put together a variety of loans and then are sold off in tranches. The tranches are ranked with the more senior ones getting the first claim to payments and least senior ones getting the last claim. This way a pool of risky loans can be used to create senior tranches with top investment grade ratings. The least senior tranches will be very risky and carry junk ratings but will offer a high rate of interest.

Pearlstein warns that the growth in CLOs has been explosive.

“Because the market seems to have an insatiable appetite for CLOs, leveraged lending and CLO issuance through the first half of the year are already up 38 percent over last year’s near-record levels.”

Sounds really scary, but how much is 38 percent above last year’s levels? Pearlstein never gives us a number, but a little digging tells us that the CLO market is just over $1 trillion. So how worried should we be?

Let’s call in Mr. Arithmetic. Suppose that 40 percent of these CLOs go bad, an extremely high percentage. That would be $400 billion in CLOs that could not be paid off in full. Of course, most people would still be getting their payments, since most of the loans in a CLO would likely still be paid. Let’s assume a loss rate of 40 percent on this $400 billion, a very high loss rate. That translates into $160 billion in losses.

Is this another financial crisis? We have a GDP of $20 trillion, making these losses equal to 0.8 percent of GDP. Arguably, our total wealth of close to $100 trillion is the better denominator, putting the losses at 0.16 percent of total wealth. Are you scared yet?

The story of the financial crisis was one of loans that were directly linked to a seriously over-valued asset that was widely held (housing). When the housing market collapsed, the loan supporting the market also collapsed, creating a downward spiral where falling house prices led to greater default rates, which also undermined the market for home purchases, further depressing prices.

The collapse in housing led to both a huge plunge in construction of 5 percent of GDP ($1 trillion annually in today’s economy) and a plunge in housing wealth driven consumption of almost 3.0 percent of GDP ($600 billion in today’s economy). That is what tanked the economy as it is not easy to find a way to replace lost demand equal to 8.0 percentage points of GDP.

This is hugely different than Pearlstein’s absurd story about CLOs crashing the economy in 2008. Of course, it doesn’t mean that we should not be worried about this risky loans. It is likely that lenders are making big bucks selling tranches to people who do not understand the risk. This is not a way to promote economic growth. This rip-off finance is a pure waste to the economy and diverts resources from productive uses. But it will not crash the economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Okay, I’m going to plead guilty to playing lawyer without a license. The NYT reports that the Trump administration is proposing to unilaterally (as in no congressional action) change the way that capital gains are calculated for tax purposes.

The plan is to allow people to index capital gains for inflation. For example, under current law, if you bought 100 shares of stock for $100 per share ten years ago, and sell the shares today for $200, you would pay the capital gains tax on the full difference of $10,000. (100* $200 = $20,000, 100* $100 = $10,000. $20,000 minus $10,000 = $10,000)

Under the Trump administration’s plan, you would be able to adjust the original $10,000 purchase for the inflation in the last decade. Let’s say that the inflation over this period has been a total of 20 percent. This means that instead of deducting $10,000 from the current sale price to calculation your gain you would deduct $12,000. This would leave a taxable gain of $8,000 instead of $10,000.

In this case it means a 20 percent reduction in the tax rate on capital gains. The reduction would be greater for longer held assets and less for assets held a short period of time.

In case there is any doubt, almost all of the savings would go to rich people. The article cites an analysis showing that 97 percent of the savings would go to the top 10 percent of the population and more than two thirds would go to the richest 0.1 percent.

And, just to be clear, don’t be foolish enough to think this is about helping the middle class Joe and Jane with their 401(k)s. These suckers have the capital gains in their 401(k)s taxed as ordinary income. They won’t be helped one iota by this change in the tax law. As the Republican motto goes, “tax cuts are for rich people.”

Now for my cheap legal thoughts. Congress has repeatedly changed the tax code with the understanding that a capital gain was defined as the difference between the selling price of an asset and the purchase price. This is one reason why the tax rate on capital gains is so much lower than the tax rate on wage income. (The top tax rate on capital gains is 20 percent, compared to 37.0 percent on wage income.)

In effect, the Trump administration would be saying that Congress didn’t know what it was doing when it was setting capital gains tax rates. That they actually meant for the gains to be indexed to inflation, it was just some weird misunderstanding that persisted for all these decades that caused capital gains to be measured by just taking actual purchase price.

I suppose this would be surprising, but given the open contempt that the Trump administration routinely shows for the rule of law, inventing a huge tax break for the richest people in the country is pretty much what we have come to expect. After all, if they didn’t get to lie, cheat, and steal, how could rich people get by on today’s rapidly changing economy?

Okay, I’m going to plead guilty to playing lawyer without a license. The NYT reports that the Trump administration is proposing to unilaterally (as in no congressional action) change the way that capital gains are calculated for tax purposes.

The plan is to allow people to index capital gains for inflation. For example, under current law, if you bought 100 shares of stock for $100 per share ten years ago, and sell the shares today for $200, you would pay the capital gains tax on the full difference of $10,000. (100* $200 = $20,000, 100* $100 = $10,000. $20,000 minus $10,000 = $10,000)

Under the Trump administration’s plan, you would be able to adjust the original $10,000 purchase for the inflation in the last decade. Let’s say that the inflation over this period has been a total of 20 percent. This means that instead of deducting $10,000 from the current sale price to calculation your gain you would deduct $12,000. This would leave a taxable gain of $8,000 instead of $10,000.

In this case it means a 20 percent reduction in the tax rate on capital gains. The reduction would be greater for longer held assets and less for assets held a short period of time.

In case there is any doubt, almost all of the savings would go to rich people. The article cites an analysis showing that 97 percent of the savings would go to the top 10 percent of the population and more than two thirds would go to the richest 0.1 percent.

And, just to be clear, don’t be foolish enough to think this is about helping the middle class Joe and Jane with their 401(k)s. These suckers have the capital gains in their 401(k)s taxed as ordinary income. They won’t be helped one iota by this change in the tax law. As the Republican motto goes, “tax cuts are for rich people.”

Now for my cheap legal thoughts. Congress has repeatedly changed the tax code with the understanding that a capital gain was defined as the difference between the selling price of an asset and the purchase price. This is one reason why the tax rate on capital gains is so much lower than the tax rate on wage income. (The top tax rate on capital gains is 20 percent, compared to 37.0 percent on wage income.)

In effect, the Trump administration would be saying that Congress didn’t know what it was doing when it was setting capital gains tax rates. That they actually meant for the gains to be indexed to inflation, it was just some weird misunderstanding that persisted for all these decades that caused capital gains to be measured by just taking actual purchase price.

I suppose this would be surprising, but given the open contempt that the Trump administration routinely shows for the rule of law, inventing a huge tax break for the richest people in the country is pretty much what we have come to expect. After all, if they didn’t get to lie, cheat, and steal, how could rich people get by on today’s rapidly changing economy?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an interesting piece on how the tight labor market is forcing trucking companies to reach out to women and minorities to hire as truckers. Trucking is an industry that had historically been dominated by white men, but with fewer white men willing to work as truckers, the article argues that the industry has no choice but to look to other demographic groups.

This is a great example of how a tight labor market disproportionately benefits the more disadvantaged segments of the population. This is why people who want to combat racial and gender inequality should be especially attentive to the policies of the Federal Reserve Board. If it needlessly raises interest rates to slow the economy, reduce job creation, and weaken the labor market, disadvantaged groups will be the main victims.

It is also worth noting that trucking companies don’t seem to be working as hard to increase pay to attract drivers as this piece implies. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average hourly wage for truckers has risen by just 2.3 percent over the last year, less than the rate of inflation.

The NYT had an interesting piece on how the tight labor market is forcing trucking companies to reach out to women and minorities to hire as truckers. Trucking is an industry that had historically been dominated by white men, but with fewer white men willing to work as truckers, the article argues that the industry has no choice but to look to other demographic groups.

This is a great example of how a tight labor market disproportionately benefits the more disadvantaged segments of the population. This is why people who want to combat racial and gender inequality should be especially attentive to the policies of the Federal Reserve Board. If it needlessly raises interest rates to slow the economy, reduce job creation, and weaken the labor market, disadvantaged groups will be the main victims.

It is also worth noting that trucking companies don’t seem to be working as hard to increase pay to attract drivers as this piece implies. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average hourly wage for truckers has risen by just 2.3 percent over the last year, less than the rate of inflation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I see that Trump seems to be claiming victory in his trade war based on a deal with the European Union to negotiate lower tariffs. I want to take some credit for calling this one based on an oped I wrote two weeks ago, but couldn’t get printed. Here’s the version I drafted on July 12th.

The End Game in Donald Trump’s Trade War

Like many economists, I have been puzzled over the likely endgame in the trade war that Donald Trump has initiated with most of our major trading partners. He has escalated his rhetoric and put together a large list of imports to be hit with tariffs. His demands are vague and continually shifting. This doesn’t look like the way to win a trade war.

But then I remembered we are talking about reality TV show host Donald Trump. Winning a trade war for this reality TV show star doesn’t mean winning a trade war in the way that economists might envision.

It’s not a question of forcing concessions from trading partners that will improve our trade balance and the overall health of the economy. It’s a question of being able to hold something up that allows Trump to declare victory. That doesn’t require much.

If it is hard to imagine Trump celebrating concessions that were either never made or agreed to long ago, then just look at what happened at the NATO summit. Our partners in NATO had agreed back in 2014 to gradually increase their military spending to 2 percent of GDP by 2024. Apparently, they are still on this course.

Trump boasted of a huge victory for his leadership, pointing to their $33 billion projected increase in military spending for next year. He touted this increase, which comes to 0.16 percent of our NATO partners’ GDP, as “really amazing.” (Most of this was simply due to inflation.)

This is not the only area in which Trump has invented things out of thin air. He has gotten tens of millions of his followers to become incredibly fearful of being killed by the MS-13 street gang. In reality, most people in this country probably stand a greater risk of death from shark attacks than MS-13, but he used these fears as the basis for his crackdown on immigration.

Donald Trump is a person for whom reality matters little, if at all. Is there any reason that he wouldn’t just proclaim victory over China in the trade war a month or two before the election? He can announce that President Xi has committed the country to allowing most US goods to enter China with little or no tariff, something to which China is already committed to do under the rules of the World Trade Organization.

He can do something similar with Canada. Trump can announce that Justin Trudeau agreed to import over $600 million worth of dairy products tariff-free each year, describing the pre-trade war status quo as a great victory.

And, we can expect something similar with the European Union. Maybe he will announce that because of his tough measures the European Union will allow US made cars to enter almost tariff-free, something that is already the case.

Is there any reason to think that Trump couldn’t get away with just declaring the pre-trade war status quo a huge victory? After all, he has Fox News, his quasi-official media outlet, to head up the cheerleading, and no shortage of Twitter followers to get the good news directly from the top.

We also already know what he will say about the sore losers who try to challenge his victory in the Great Trade War with facts. This will all be “FAKE NEWS!”

This scenario seems so obvious that it’s amazing anyone ever thought any other outcome was possible. For a president who invents his own reality, why would he not just invent a victory in a trade war that looks likely to turn out badly based on the course he has taken?

Many years ago, George Aiken, a distinguished Republican senator from Vermont, came up with the idea of declaring victory in Vietnam and going home. The proposal was largely in jest, but it stemmed from a reality that we seemed to be mired in an endless war that served no obvious purpose. In that context, a meaningless declaration of victory, coupled with an ending of the war would have been a very good plan.

Half a century later, we are entering a trade war that serves no productive purpose over imaginary wrongs. We can all be happy if Trump ends the war before there is too much damage to the economy and people’s lives. His declaration of victory will be less laudable than Senator’s Aiken’s, but at least this pointless war will have come to an end.

I see that Trump seems to be claiming victory in his trade war based on a deal with the European Union to negotiate lower tariffs. I want to take some credit for calling this one based on an oped I wrote two weeks ago, but couldn’t get printed. Here’s the version I drafted on July 12th.

The End Game in Donald Trump’s Trade War

Like many economists, I have been puzzled over the likely endgame in the trade war that Donald Trump has initiated with most of our major trading partners. He has escalated his rhetoric and put together a large list of imports to be hit with tariffs. His demands are vague and continually shifting. This doesn’t look like the way to win a trade war.

But then I remembered we are talking about reality TV show host Donald Trump. Winning a trade war for this reality TV show star doesn’t mean winning a trade war in the way that economists might envision.

It’s not a question of forcing concessions from trading partners that will improve our trade balance and the overall health of the economy. It’s a question of being able to hold something up that allows Trump to declare victory. That doesn’t require much.

If it is hard to imagine Trump celebrating concessions that were either never made or agreed to long ago, then just look at what happened at the NATO summit. Our partners in NATO had agreed back in 2014 to gradually increase their military spending to 2 percent of GDP by 2024. Apparently, they are still on this course.

Trump boasted of a huge victory for his leadership, pointing to their $33 billion projected increase in military spending for next year. He touted this increase, which comes to 0.16 percent of our NATO partners’ GDP, as “really amazing.” (Most of this was simply due to inflation.)

This is not the only area in which Trump has invented things out of thin air. He has gotten tens of millions of his followers to become incredibly fearful of being killed by the MS-13 street gang. In reality, most people in this country probably stand a greater risk of death from shark attacks than MS-13, but he used these fears as the basis for his crackdown on immigration.

Donald Trump is a person for whom reality matters little, if at all. Is there any reason that he wouldn’t just proclaim victory over China in the trade war a month or two before the election? He can announce that President Xi has committed the country to allowing most US goods to enter China with little or no tariff, something to which China is already committed to do under the rules of the World Trade Organization.

He can do something similar with Canada. Trump can announce that Justin Trudeau agreed to import over $600 million worth of dairy products tariff-free each year, describing the pre-trade war status quo as a great victory.

And, we can expect something similar with the European Union. Maybe he will announce that because of his tough measures the European Union will allow US made cars to enter almost tariff-free, something that is already the case.

Is there any reason to think that Trump couldn’t get away with just declaring the pre-trade war status quo a huge victory? After all, he has Fox News, his quasi-official media outlet, to head up the cheerleading, and no shortage of Twitter followers to get the good news directly from the top.

We also already know what he will say about the sore losers who try to challenge his victory in the Great Trade War with facts. This will all be “FAKE NEWS!”

This scenario seems so obvious that it’s amazing anyone ever thought any other outcome was possible. For a president who invents his own reality, why would he not just invent a victory in a trade war that looks likely to turn out badly based on the course he has taken?

Many years ago, George Aiken, a distinguished Republican senator from Vermont, came up with the idea of declaring victory in Vietnam and going home. The proposal was largely in jest, but it stemmed from a reality that we seemed to be mired in an endless war that served no obvious purpose. In that context, a meaningless declaration of victory, coupled with an ending of the war would have been a very good plan.

Half a century later, we are entering a trade war that serves no productive purpose over imaginary wrongs. We can all be happy if Trump ends the war before there is too much damage to the economy and people’s lives. His declaration of victory will be less laudable than Senator’s Aiken’s, but at least this pointless war will have come to an end.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The headline of the piece told readers “Wages are rising in Europe. But economists are puzzled.” Yes, well it does seem pretty puzzling, since it’s not clear what wage increases the piece is talking about.

Here is the key paragraph:

“When official data last month showed that hourly wages in the eurozone rose 2 percent in the first three months of 2018 — finally — the central bank got the signal it was looking for. It announced it would end its main stimulus measure at the end of the year. At its meeting on Thursday, the Governing Council is expected to reaffirm that plan.”

Okay, 2.0 percent growth in the average hourly wage over the last year. This appears to be nominal wages, which in the context of the eurozone’s 2.0 percent inflation, translates into exactly 0.0 percent real wage growth.

I double-checked this looking at the eurostat data and it did, in fact, show that average hourly wages in the eurozone had gone up 2.0 percent over the last year in nominal terms. In other words, zero increase in real wages. Furthermore, while the 2.0 percent year-over-year increase shown in the first quarter was up from 1.4 percent in the fourth quarter of 2017, the increase had been 1.8 percent in the second quarter of 2017 as well as the first quarter of 2016.

If we use the first quarter 2016 figure as a reference point, the rate of wage growth has accelerated 0.2 percentage points in two years or 0.1 percentage point annually. This merits a major NYT story? Yes, I am puzzled.

The headline of the piece told readers “Wages are rising in Europe. But economists are puzzled.” Yes, well it does seem pretty puzzling, since it’s not clear what wage increases the piece is talking about.

Here is the key paragraph:

“When official data last month showed that hourly wages in the eurozone rose 2 percent in the first three months of 2018 — finally — the central bank got the signal it was looking for. It announced it would end its main stimulus measure at the end of the year. At its meeting on Thursday, the Governing Council is expected to reaffirm that plan.”

Okay, 2.0 percent growth in the average hourly wage over the last year. This appears to be nominal wages, which in the context of the eurozone’s 2.0 percent inflation, translates into exactly 0.0 percent real wage growth.

I double-checked this looking at the eurostat data and it did, in fact, show that average hourly wages in the eurozone had gone up 2.0 percent over the last year in nominal terms. In other words, zero increase in real wages. Furthermore, while the 2.0 percent year-over-year increase shown in the first quarter was up from 1.4 percent in the fourth quarter of 2017, the increase had been 1.8 percent in the second quarter of 2017 as well as the first quarter of 2016.

If we use the first quarter 2016 figure as a reference point, the rate of wage growth has accelerated 0.2 percentage points in two years or 0.1 percentage point annually. This merits a major NYT story? Yes, I am puzzled.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Wall Street Journal may have gotten a bit carried away in telling readers that manufacturing had hit a “sweet spot” based on the Fed’s data on manufacturing production in June. The immediate story was the Federal Reserve Board’s report that manufacturing production had increased 0.8 percent in June following a 1.0 drop in May. The May decline was the result of a fire at a parts supplier for Ford.

While the bounce-back was encouraging, it still means that for the two-month period manufacturing output was down 0.2 percent. It seems hard to view this as positive news for the sector. Monthly data are erratic, so it is entirely possible that this decline will be offset by stronger growth in July and subsequent months, but it seems hard to view the June data as especially positive.

It is also worth noting that the longer term picture hardly suggests a boom for the sector. Here’s the picture going back to 2000. Output was growing much faster in the early years of the recovery. There were also periods in 2014 and 2015 when output increased at a similar pace. The near zero growth from 2000 to 2004 was due to the explosion of the trade deficit.

The Wall Street Journal may have gotten a bit carried away in telling readers that manufacturing had hit a “sweet spot” based on the Fed’s data on manufacturing production in June. The immediate story was the Federal Reserve Board’s report that manufacturing production had increased 0.8 percent in June following a 1.0 drop in May. The May decline was the result of a fire at a parts supplier for Ford.

While the bounce-back was encouraging, it still means that for the two-month period manufacturing output was down 0.2 percent. It seems hard to view this as positive news for the sector. Monthly data are erratic, so it is entirely possible that this decline will be offset by stronger growth in July and subsequent months, but it seems hard to view the June data as especially positive.

It is also worth noting that the longer term picture hardly suggests a boom for the sector. Here’s the picture going back to 2000. Output was growing much faster in the early years of the recovery. There were also periods in 2014 and 2015 when output increased at a similar pace. The near zero growth from 2000 to 2004 was due to the explosion of the trade deficit.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión