Most candidates would not make a huge tax hike a center piece in their presidential campaign, but Donald Trump is not your typical presidential candidate. In case people missed it, Trump floated the idea of imposing 10 percent tariffs across the board on all imports with a group of people who have served as his economic advisers.

It’s not clear whether this tariff is supposed to be in addition to current tariffs or a replacement. In the case of items coming in from China, it would actually imply a cut from the current tariff rate, which averages 19 percent now. It’s also not clear whether it would apply to imports of services, most of which are not subject to tariffs.

Recognizing these ambiguities, let’s say that the tariff is an addition to current tariffs and applies to all goods imports, but not services. This can give us a rough estimate of how much Trump’s tariffs will be increasing taxes for people in the United States.

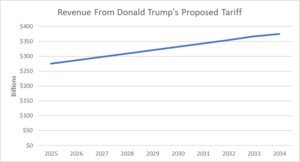

The Congressional Budget Office projects that we will import $49.3 trillion of goods and services over the decade from 2025 to 2034. (I increased the projection for 2033 by 3.4 percent, the prior year’s growth rate, to get the figure for 2034.) If we assume that 81.8 percent of these imports will be goods (the share for the first half of 2023), then goods imports will be $40.3 trillion over this period.

The tariff will have some impact on both the quantity of imports and the prices received by the countries that export to us. I have assumed that the quantity of imports falls by 10 percent in response to the tariffs, while the price of imports falls by 1.0 percent. Here is the picture for the amount of revenue – the taxes – that we will be paying year by year as a result of Trump’s tariffs.

Source: Congressional Budget Office and author’s calculations.

The sum for the period is a bit under $3.6 trillion. It is a bit more than 0.9 percent of GDP over this period. This would be a substantial sum out of people’s pockets ($11,000 per person), and would likely be a substantial drag on GDP growth.

Note: An earlier version assumed import prices dropped by 10 percent in response to the tariffs. I had meant to assume that the price decline was 10 percent of the tariff, or 1 percent of the pre-tariff price.

Most candidates would not make a huge tax hike a center piece in their presidential campaign, but Donald Trump is not your typical presidential candidate. In case people missed it, Trump floated the idea of imposing 10 percent tariffs across the board on all imports with a group of people who have served as his economic advisers.

It’s not clear whether this tariff is supposed to be in addition to current tariffs or a replacement. In the case of items coming in from China, it would actually imply a cut from the current tariff rate, which averages 19 percent now. It’s also not clear whether it would apply to imports of services, most of which are not subject to tariffs.

Recognizing these ambiguities, let’s say that the tariff is an addition to current tariffs and applies to all goods imports, but not services. This can give us a rough estimate of how much Trump’s tariffs will be increasing taxes for people in the United States.

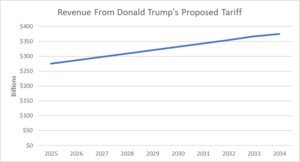

The Congressional Budget Office projects that we will import $49.3 trillion of goods and services over the decade from 2025 to 2034. (I increased the projection for 2033 by 3.4 percent, the prior year’s growth rate, to get the figure for 2034.) If we assume that 81.8 percent of these imports will be goods (the share for the first half of 2023), then goods imports will be $40.3 trillion over this period.

The tariff will have some impact on both the quantity of imports and the prices received by the countries that export to us. I have assumed that the quantity of imports falls by 10 percent in response to the tariffs, while the price of imports falls by 1.0 percent. Here is the picture for the amount of revenue – the taxes – that we will be paying year by year as a result of Trump’s tariffs.

Source: Congressional Budget Office and author’s calculations.

The sum for the period is a bit under $3.6 trillion. It is a bit more than 0.9 percent of GDP over this period. This would be a substantial sum out of people’s pockets ($11,000 per person), and would likely be a substantial drag on GDP growth.

Note: An earlier version assumed import prices dropped by 10 percent in response to the tariffs. I had meant to assume that the price decline was 10 percent of the tariff, or 1 percent of the pre-tariff price.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Shawn Fain, the president of the United Auto Workers, said that he viewed the 40 percent pay increases received by the auto industry’s CEOs as a benchmark for the pay increase the union’s members should be receiving in their next contract. It’s not clear if he intends to make the pay of the CEOs and other top management a topic in negotiations, but it would be great if he did.

While there has been some shift from wages to profits over the last four decades, most of the upward redistribution went from ordinary workers to high-end workers like CEOs and other top managers, Wall Street types, and the elite in the tech sector. If the union can put some serious downward pressure on the pay of top management it could be a big step in reversing this upward redistribution.

The problem with CEO pay is that there is no effective check on it. For ordinary workers, managers know that they can boost the company’s profits if they can force workers to accept lower pay. But, there is no one trying to force lower pay on top management.

Ostensibly, corporate boards of directors are supposed to be keeping a lid on CEO pay, since in principle they represent shareholders. However, there is little reason to believe that they act as the textbook says Top management typically plays a large role in selecting directors.

And, once a director is appointed they are virtually assured of keeping their job as long as they remain on good terms with the other directors. Directors who are nominated for re-election by the board, win their elections more than 99 percent of the time. This means that they have little incentive to ask pesky questions, like “can we pay our CEO less?”

Being a director pays very well, with the average director of a major company getting pay and options worth several hundred thousand dollars a year for around 400 hours of work. It’s good work, if you can get it.

As a result, most CEOs don’t even see their job as involving reining in the pay of top management. Instead, they view themselves as serving top management, helping them to achieve their goals.

This is a big deal because the high pay received by CEOs and other top management corrupts pay scales throughout the economy. If the CEO is getting $20-$30 million, then the next level of management is likely getting $10-$15 million, and the third-tier executives are likely getting $2-$3 million.

And, these bloated pay structures in the corporate sector spill over to the rest of the economy. The CEOs of major universities or large charities often get $2-$3 million a year, and their top assistants can get pay of close to $1 million. Pay structures have become so distorted that many people now consider it a major sacrifice to work in top government positions that pay around $200,000 a year.

This picture would change radically if we could put some serious downward pressure on the pay of CEOs. If we were back in the world of the 1960s-70s, CEOs would be earning 20 to 30 times the pay of ordinary workers rather than 200-300 times. This would put their pay in the range of $2-$3 million a year. Think of how different the world would look if the CEOs at our largest most successful companies were pocketing $3 million a year, instead of $30 million, or even more.

Mary Barra, the CEO of GM, pocketed just under $29 million last year. Good luck to the union in trying to bring that figure down to earth. They will be doing the whole country a service.

Shawn Fain, the president of the United Auto Workers, said that he viewed the 40 percent pay increases received by the auto industry’s CEOs as a benchmark for the pay increase the union’s members should be receiving in their next contract. It’s not clear if he intends to make the pay of the CEOs and other top management a topic in negotiations, but it would be great if he did.

While there has been some shift from wages to profits over the last four decades, most of the upward redistribution went from ordinary workers to high-end workers like CEOs and other top managers, Wall Street types, and the elite in the tech sector. If the union can put some serious downward pressure on the pay of top management it could be a big step in reversing this upward redistribution.

The problem with CEO pay is that there is no effective check on it. For ordinary workers, managers know that they can boost the company’s profits if they can force workers to accept lower pay. But, there is no one trying to force lower pay on top management.

Ostensibly, corporate boards of directors are supposed to be keeping a lid on CEO pay, since in principle they represent shareholders. However, there is little reason to believe that they act as the textbook says Top management typically plays a large role in selecting directors.

And, once a director is appointed they are virtually assured of keeping their job as long as they remain on good terms with the other directors. Directors who are nominated for re-election by the board, win their elections more than 99 percent of the time. This means that they have little incentive to ask pesky questions, like “can we pay our CEO less?”

Being a director pays very well, with the average director of a major company getting pay and options worth several hundred thousand dollars a year for around 400 hours of work. It’s good work, if you can get it.

As a result, most CEOs don’t even see their job as involving reining in the pay of top management. Instead, they view themselves as serving top management, helping them to achieve their goals.

This is a big deal because the high pay received by CEOs and other top management corrupts pay scales throughout the economy. If the CEO is getting $20-$30 million, then the next level of management is likely getting $10-$15 million, and the third-tier executives are likely getting $2-$3 million.

And, these bloated pay structures in the corporate sector spill over to the rest of the economy. The CEOs of major universities or large charities often get $2-$3 million a year, and their top assistants can get pay of close to $1 million. Pay structures have become so distorted that many people now consider it a major sacrifice to work in top government positions that pay around $200,000 a year.

This picture would change radically if we could put some serious downward pressure on the pay of CEOs. If we were back in the world of the 1960s-70s, CEOs would be earning 20 to 30 times the pay of ordinary workers rather than 200-300 times. This would put their pay in the range of $2-$3 million a year. Think of how different the world would look if the CEOs at our largest most successful companies were pocketing $3 million a year, instead of $30 million, or even more.

Mary Barra, the CEO of GM, pocketed just under $29 million last year. Good luck to the union in trying to bring that figure down to earth. They will be doing the whole country a service.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The United States suffered from a massive loss of manufacturing jobs in the 00s. This has come to be known as the “China Shock,” since it was associated with a flood of imports, especially from China, and a rapid rise in the U.S. trade deficit.

In the decade from December of 1999 to December of 2009, the economy lost more than 5.8 million manufacturing jobs, or more than one in three of the manufacturing jobs at the start of the decade. The vast majority of this job loss took place before the start of the Great Recession in December of 2007.

This sort of job loss was not typical for the manufacturing sector. While it lost jobs in the 1990s also, the drop was just 601,000, a bit more than one tenth as much as in the next decade. Since 2009, the manufacturing sector has actually been adding jobs, so the plunge in jobs in the manufacturing sector in the first decade of this century really was an anomaly.

The loss of manufacturing jobs, which had been more highly unionized and better paying than most jobs in the private sector, also had a devastating impact on many cities and towns across the industrial Midwest. When the manufacturing jobs left town, so did much of the tax revenue and purchasing power.

A recent piece in the Guardian implied that the job loss associated with a green transition could provide a comparable hit to the labor market. This is not true.

The number of jobs plausibly at stake in a green transition is almost certainly less than one-tenth as large as was the case with the China shock. The basis for the Guardian piece is a recent NBER paper by Mark Curtis, Layla Kane, and Jisung Park, that looked at what happened to workers who transitioned out of jobs in fossil fuels or related industries. The paper found that a relatively small share of these workers found jobs in green sectors of the economy. It also found that a large share of these workers ending up taking jobs in occupations that paid considerably less than the jobs they lost.

While this is not a good picture, it is important to get a sense of the number of workers involved. The paper analyzed just over 1.7 million transitions from jobs in fossil fuels and related industries, over the 21 years from 2002-2022.[1] By comparison, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey indicate that there were more than 44 million instances where workers left or were fired from manufacturing jobs, in the nine years from 2001 through 2009. (The Survey starts in December of 2000.)[2]

These figures are not entirely comparable, since presumably people who retired or dropped out of the labor force were not counted as making transitions in the Curtis, Kane, and Park piece. Also, some of the people in the JOLTS data likely appear multiple times from the same job. For example, if a worker was laid off more than once from a job, they could count two or more times in the JOLTS data, whereas they would not be counted as making a transition unless they found a new job with another employer.

While recognizing these inconsistencies, it is still likely the case that the number of people leaving manufacturing jobs in the nine years from 2001 to 2009 was close to 20 times as large as the number of people transitioning out of fossil fuels and related industries in the 21 years from 2002 to 2022. Adjusting for the differences in the number of years, the job loss in manufacturing is close to forty times as much on an annual basis as the transitions associated with the shift to a green economy.

The job loss associated with the conversion to a green economy should not be trivialized. For many workers and their families, the loss of a good-paying job in the oil or gas industry can be traumatic. In many cases they will never find a job that pays a comparable wage. But it is a mistake to imply that the number of jobs at risk is comparable to the number of manufacturing jobs lost to trade in the first decade of the century.

It would be great if government support can facilitate the transitions for the affected workers, but the downside risk here is nowhere near as large as what we saw due to the opening of trade in manufacturing goods in the 00s. It would be unfortunate if the fossil fuel industry used this risk as an excuse to slow the transition to a green economy.

[1] This number was obtained by using the percentage of transitions from each sector in Tables 2a and 2b.

[2] Job turnover is much less than net job loss because new workers typically fill jobs that other workers left, and job creation in factories that are growing offsets job loss in factories with declining employment.

The United States suffered from a massive loss of manufacturing jobs in the 00s. This has come to be known as the “China Shock,” since it was associated with a flood of imports, especially from China, and a rapid rise in the U.S. trade deficit.

In the decade from December of 1999 to December of 2009, the economy lost more than 5.8 million manufacturing jobs, or more than one in three of the manufacturing jobs at the start of the decade. The vast majority of this job loss took place before the start of the Great Recession in December of 2007.

This sort of job loss was not typical for the manufacturing sector. While it lost jobs in the 1990s also, the drop was just 601,000, a bit more than one tenth as much as in the next decade. Since 2009, the manufacturing sector has actually been adding jobs, so the plunge in jobs in the manufacturing sector in the first decade of this century really was an anomaly.

The loss of manufacturing jobs, which had been more highly unionized and better paying than most jobs in the private sector, also had a devastating impact on many cities and towns across the industrial Midwest. When the manufacturing jobs left town, so did much of the tax revenue and purchasing power.

A recent piece in the Guardian implied that the job loss associated with a green transition could provide a comparable hit to the labor market. This is not true.

The number of jobs plausibly at stake in a green transition is almost certainly less than one-tenth as large as was the case with the China shock. The basis for the Guardian piece is a recent NBER paper by Mark Curtis, Layla Kane, and Jisung Park, that looked at what happened to workers who transitioned out of jobs in fossil fuels or related industries. The paper found that a relatively small share of these workers found jobs in green sectors of the economy. It also found that a large share of these workers ending up taking jobs in occupations that paid considerably less than the jobs they lost.

While this is not a good picture, it is important to get a sense of the number of workers involved. The paper analyzed just over 1.7 million transitions from jobs in fossil fuels and related industries, over the 21 years from 2002-2022.[1] By comparison, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey indicate that there were more than 44 million instances where workers left or were fired from manufacturing jobs, in the nine years from 2001 through 2009. (The Survey starts in December of 2000.)[2]

These figures are not entirely comparable, since presumably people who retired or dropped out of the labor force were not counted as making transitions in the Curtis, Kane, and Park piece. Also, some of the people in the JOLTS data likely appear multiple times from the same job. For example, if a worker was laid off more than once from a job, they could count two or more times in the JOLTS data, whereas they would not be counted as making a transition unless they found a new job with another employer.

While recognizing these inconsistencies, it is still likely the case that the number of people leaving manufacturing jobs in the nine years from 2001 to 2009 was close to 20 times as large as the number of people transitioning out of fossil fuels and related industries in the 21 years from 2002 to 2022. Adjusting for the differences in the number of years, the job loss in manufacturing is close to forty times as much on an annual basis as the transitions associated with the shift to a green economy.

The job loss associated with the conversion to a green economy should not be trivialized. For many workers and their families, the loss of a good-paying job in the oil or gas industry can be traumatic. In many cases they will never find a job that pays a comparable wage. But it is a mistake to imply that the number of jobs at risk is comparable to the number of manufacturing jobs lost to trade in the first decade of the century.

It would be great if government support can facilitate the transitions for the affected workers, but the downside risk here is nowhere near as large as what we saw due to the opening of trade in manufacturing goods in the 00s. It would be unfortunate if the fossil fuel industry used this risk as an excuse to slow the transition to a green economy.

[1] This number was obtained by using the percentage of transitions from each sector in Tables 2a and 2b.

[2] Job turnover is much less than net job loss because new workers typically fill jobs that other workers left, and job creation in factories that are growing offsets job loss in factories with declining employment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

David Streitfield had an interesting piece in the NYT on an ongoing legal battle between a group of publishers and an online library. The central issue is the extent to which copyright can apply to digital copies of books and other printed material held by the library.

The piece runs through the various legal decisions on the extent to which copyright restricts digital sharing. The question is once the library has bought an item or had it donated, does it then have the right to freely share it, as would be the case with a physical copy?

I’ll leave the legal issues here to lawyers and legal scholars and instead ask what ultimately is at issue. Copyright monopolies are the mechanism we have used to support the vast majority of creative work in this country. At least a small number of writers, musicians, singers, and other creative workers are able to make a decent, or even extraordinary, living through this mechanism. The vast majority of people who choose these careers earn very little through copyright, but even a little can be better than nothing.

Over the last half-century, Congress has repeatedly made the duration of copyright longer, extending it from 56 years as of 1976, to 95 years after 1998. Incredibly, it made these extensions retroactive so that works that would have seen their copyright expire instead had years added to the duration by these acts of Congress. It is hard to imagine a serious rationale for these retroactive extensions since we can’t increase the incentives that creative workers saw in the past.

Congress also adjusted the laws for the digital age and set in place rules for copyright enforcement for online platforms. While Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act shields a platform like Facebook or Twitter from liability for any defamatory material their users may post, the same is not true for copyright infringement. The Digital Millennial Copyright Act requires them to promptly remove any infringing material after the alleged infringement has been called to their attention. Since platforms generally want to avoid copyright suits, they have arguably over-removed material, pulling down items where the copyright claim is dubious or the material would arguably be protected as fair use.

A main reason that Internet hosts tend to be quick to remove material in response to an alleged infringement is that the law allows for statutory damages for copyright infringement. This is a big deal because statutory damages can often be hundreds of times the amount of actual damages. In addition, the judge can also award attorney’s fees.

This makes a huge difference when it comes to enforcement. Take the case of a song that is posted in clear violation of copyright. Suppose it is streamed 10,000 times as a result of this unauthorized posting, which would be a lot for most songs and most websites. Spotify pays artists between $0.003 and $0.005 per stream. That means that the actual damages in this case would be between $30 and $50. That’s not an amount that most people would file a suit over, especially if they could not expect to collect attorney’s fees, even if they win.

There would be even less at stake with a less frequented website where maybe 50 or 100 copies may be streamed. Or, in the case of a copyrighted book or article that is perhaps ten or twenty years old, the actual damages would likely be in the single digit dollars. In other words, the laws on copyright provide incentives for lawsuits even when the actual damages involved are trivial.

To think of the analogous situation, suppose that we had statutory damages for trespassing. This would give people incentive to file lawsuits for even trivial acts of trespass, such as cutting the corner over the edge of someone’s lawn, or a dog sniffing in someone’s bushes. We would end up, as a society, spending a lot more money on lawyers for no plausible gain. Arguably, this is the story with copyright enforcement today.

Bringing Copyright in the 21st Century

Given the trivial amount of money at stake in the vast majority of instances of alleged copyright infringement, it can’t make sense to provide statutory damages to copyright holders. Even if we think copyright is a good mechanism for financing creative work, there is no obvious reason that copyright holders need to get compensated beyond their actual damages for instances of infringement. If the actual damages from an act of infringement are trivial, why would we want to encourage lawsuits over small sums of money?

As a practical matter, many acts of infringement may actually end up being a net gain for creative workers. Suppose a person had one hundred unauthorized streams of a musician’s songs. Based on Spotify’s compensation rate, the loss to the artist would be between 30 and 50 cents, assuming that the person would have been willing to pay for the streams, if they did not have a free option.

But suppose they decided they liked this musician after hearing these unauthorized streams. As a result, they may in the future be willing to pay for recorded material or even to hear them live. In this scenario, preventing the unauthorized streams deprived the musician of a future customer.

If that scenario seems far-fetched, remember I specified that the person listened to unauthorized streams one hundred times. Presumably, someone would only listen to a version of a song or songs one hundred times if they liked the music. If they didn’t like the music, then they would likely only listen to a small number of unauthorized streams, say 5-10, implying actual damages in the single digit pennies.

Without statutory damages, the issues raised in the Streitfield article would largely disappear. A digital library that made older books and articles available, in possible violation of copyright, would be inflicting trivial damages in almost all cases. No one is going to hire a lawyer and file a suit to recover $50-$100 in potential losses of royalty payments. The cases where the library might face a plausible claim of any real size for actual damages would almost certainly be few and far between. Dealing with these claims would impose a modest expense that the library could likely bear, just as it probably has to pay for water and electricity.

They probably would be advised not to post a newly released Taylor Swift recording or Steven King book, but even with these superstars they probably would not have much to worry about after five or ten years. The number of copies being streamed or downloaded would likely be at best marginally profitable to file a suit over.

I haven’t made a secret of my dislike of copyright, but I am sympathetic to the idea that we should respect the copyrights that have already been granted, just as we would respect property in land after the government has sold it off, even if it got a bad price. However, this isn’t an issue of not respecting copyright, it is a question of changing enforcement rules.

Even without statutory damages, copyright holders have the right to sue and collect any actual damages that they suffer from infringement. They just don’t get the extra bonus of statutory damages.

Governments change enforcement rules literally all the time. To take an example that got considerable attention when it took effect, in 2005, Congress passed a bankruptcy reform bill. This change made it far more difficult for debtors to declare bankruptcy and discharge debt. Congress applied this change retroactively, meaning that people who took out debt under the old bankruptcy law were now subject to collection under the new law. This retroactive application of the new bankruptcy law was not even an issue.

In this context, it’s hard to see any basis for copyright holders complaining about losing their ability to collect statutory damages, although they would obviously be unhappy about the prospect of getting less income from their work. The benefit to society from free access to a vast amount of material, without having to worry about copyright claims should swamp this loss. And, we would not be wasting so many resources enforcing copyright. Lawyers who spend their time harassing website owners and Internet platforms over alleged infringement could instead do something productive with their time.

An Alternative to Copyright

Creative workers do deserve to be compensated for their work. It is not their fault that we have chosen an incredibly archaic and inefficient mechanism for this task. I have proposed a system of tax credits where every person has a certain sum (e.g. $100 to $200) as a credit which they can give to the creative worker(s) of their choice. They alternatively can give it to an organization that supports creative work in certain areas, such as country music or mystery novels. (I discuss this in chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free] and also here.)

The model for this sort of system would be the tax deduction for charitable contributions. To be eligible to get money under the system, an individual or organization would have to register with the I.R.S. just as a religious organization or charity must do now.

The registration would simply indicate what creative work an individual does or an organization supports. The I.R.S. would not make any effort to assess the quality of a musician’s performance or a writer’s books, it would just keep a record of what they claim to do just as is the case with churches and charities. If there is a question of fraud, the I.R.S. could determine if the individual or organization actually does what they claim.

There would also be a condition that creative workers who receive money through the system don’t have the option of getting copyright protection for a substantial period of time (e.g. 3-5 years). The logic here is that the government only gives creative workers one subsidy, not two. If people choose to get money through the tax credit system, they are not also entitled to a copyright monopoly.

A nice feature of this system is that it is self-enforcing. If someone is getting support through the tax credit system, but then tries to secure a copyright in the period in which they are not eligible, the copyright would be unenforceable. If they attempted to file an infringement suit, the defendant need only point out that the creative worker was in the tax credit system and the case would be immediately dismissed.

This sort of tax credit system could support a huge amount of creative work. If the credit was $100 and 200 million people chose to take advantage of it, that would generate $20 billion a year to support creative workers. A $200 credit would generate $40 billion a year. By comparison, in 2022 the United States spent $16.1 billion on music streaming services.

Of course, there can be no guarantee that everyone who wanted to do creative work would be able to support themselves through this system, just as there is no guarantee under the copyright system. What we can say is that there would be much less money wasted supporting an archaic legal construct and harassing people like Brewster Kahle, the creator of the digital archive at the center of the Streitfield piece.

Streitfield begins his article with the famous line “information wants to be free.” With a system of tax credits to support creative work, it would genuinely be free.

David Streitfield had an interesting piece in the NYT on an ongoing legal battle between a group of publishers and an online library. The central issue is the extent to which copyright can apply to digital copies of books and other printed material held by the library.

The piece runs through the various legal decisions on the extent to which copyright restricts digital sharing. The question is once the library has bought an item or had it donated, does it then have the right to freely share it, as would be the case with a physical copy?

I’ll leave the legal issues here to lawyers and legal scholars and instead ask what ultimately is at issue. Copyright monopolies are the mechanism we have used to support the vast majority of creative work in this country. At least a small number of writers, musicians, singers, and other creative workers are able to make a decent, or even extraordinary, living through this mechanism. The vast majority of people who choose these careers earn very little through copyright, but even a little can be better than nothing.

Over the last half-century, Congress has repeatedly made the duration of copyright longer, extending it from 56 years as of 1976, to 95 years after 1998. Incredibly, it made these extensions retroactive so that works that would have seen their copyright expire instead had years added to the duration by these acts of Congress. It is hard to imagine a serious rationale for these retroactive extensions since we can’t increase the incentives that creative workers saw in the past.

Congress also adjusted the laws for the digital age and set in place rules for copyright enforcement for online platforms. While Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act shields a platform like Facebook or Twitter from liability for any defamatory material their users may post, the same is not true for copyright infringement. The Digital Millennial Copyright Act requires them to promptly remove any infringing material after the alleged infringement has been called to their attention. Since platforms generally want to avoid copyright suits, they have arguably over-removed material, pulling down items where the copyright claim is dubious or the material would arguably be protected as fair use.

A main reason that Internet hosts tend to be quick to remove material in response to an alleged infringement is that the law allows for statutory damages for copyright infringement. This is a big deal because statutory damages can often be hundreds of times the amount of actual damages. In addition, the judge can also award attorney’s fees.

This makes a huge difference when it comes to enforcement. Take the case of a song that is posted in clear violation of copyright. Suppose it is streamed 10,000 times as a result of this unauthorized posting, which would be a lot for most songs and most websites. Spotify pays artists between $0.003 and $0.005 per stream. That means that the actual damages in this case would be between $30 and $50. That’s not an amount that most people would file a suit over, especially if they could not expect to collect attorney’s fees, even if they win.

There would be even less at stake with a less frequented website where maybe 50 or 100 copies may be streamed. Or, in the case of a copyrighted book or article that is perhaps ten or twenty years old, the actual damages would likely be in the single digit dollars. In other words, the laws on copyright provide incentives for lawsuits even when the actual damages involved are trivial.

To think of the analogous situation, suppose that we had statutory damages for trespassing. This would give people incentive to file lawsuits for even trivial acts of trespass, such as cutting the corner over the edge of someone’s lawn, or a dog sniffing in someone’s bushes. We would end up, as a society, spending a lot more money on lawyers for no plausible gain. Arguably, this is the story with copyright enforcement today.

Bringing Copyright in the 21st Century

Given the trivial amount of money at stake in the vast majority of instances of alleged copyright infringement, it can’t make sense to provide statutory damages to copyright holders. Even if we think copyright is a good mechanism for financing creative work, there is no obvious reason that copyright holders need to get compensated beyond their actual damages for instances of infringement. If the actual damages from an act of infringement are trivial, why would we want to encourage lawsuits over small sums of money?

As a practical matter, many acts of infringement may actually end up being a net gain for creative workers. Suppose a person had one hundred unauthorized streams of a musician’s songs. Based on Spotify’s compensation rate, the loss to the artist would be between 30 and 50 cents, assuming that the person would have been willing to pay for the streams, if they did not have a free option.

But suppose they decided they liked this musician after hearing these unauthorized streams. As a result, they may in the future be willing to pay for recorded material or even to hear them live. In this scenario, preventing the unauthorized streams deprived the musician of a future customer.

If that scenario seems far-fetched, remember I specified that the person listened to unauthorized streams one hundred times. Presumably, someone would only listen to a version of a song or songs one hundred times if they liked the music. If they didn’t like the music, then they would likely only listen to a small number of unauthorized streams, say 5-10, implying actual damages in the single digit pennies.

Without statutory damages, the issues raised in the Streitfield article would largely disappear. A digital library that made older books and articles available, in possible violation of copyright, would be inflicting trivial damages in almost all cases. No one is going to hire a lawyer and file a suit to recover $50-$100 in potential losses of royalty payments. The cases where the library might face a plausible claim of any real size for actual damages would almost certainly be few and far between. Dealing with these claims would impose a modest expense that the library could likely bear, just as it probably has to pay for water and electricity.

They probably would be advised not to post a newly released Taylor Swift recording or Steven King book, but even with these superstars they probably would not have much to worry about after five or ten years. The number of copies being streamed or downloaded would likely be at best marginally profitable to file a suit over.

I haven’t made a secret of my dislike of copyright, but I am sympathetic to the idea that we should respect the copyrights that have already been granted, just as we would respect property in land after the government has sold it off, even if it got a bad price. However, this isn’t an issue of not respecting copyright, it is a question of changing enforcement rules.

Even without statutory damages, copyright holders have the right to sue and collect any actual damages that they suffer from infringement. They just don’t get the extra bonus of statutory damages.

Governments change enforcement rules literally all the time. To take an example that got considerable attention when it took effect, in 2005, Congress passed a bankruptcy reform bill. This change made it far more difficult for debtors to declare bankruptcy and discharge debt. Congress applied this change retroactively, meaning that people who took out debt under the old bankruptcy law were now subject to collection under the new law. This retroactive application of the new bankruptcy law was not even an issue.

In this context, it’s hard to see any basis for copyright holders complaining about losing their ability to collect statutory damages, although they would obviously be unhappy about the prospect of getting less income from their work. The benefit to society from free access to a vast amount of material, without having to worry about copyright claims should swamp this loss. And, we would not be wasting so many resources enforcing copyright. Lawyers who spend their time harassing website owners and Internet platforms over alleged infringement could instead do something productive with their time.

An Alternative to Copyright

Creative workers do deserve to be compensated for their work. It is not their fault that we have chosen an incredibly archaic and inefficient mechanism for this task. I have proposed a system of tax credits where every person has a certain sum (e.g. $100 to $200) as a credit which they can give to the creative worker(s) of their choice. They alternatively can give it to an organization that supports creative work in certain areas, such as country music or mystery novels. (I discuss this in chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free] and also here.)

The model for this sort of system would be the tax deduction for charitable contributions. To be eligible to get money under the system, an individual or organization would have to register with the I.R.S. just as a religious organization or charity must do now.

The registration would simply indicate what creative work an individual does or an organization supports. The I.R.S. would not make any effort to assess the quality of a musician’s performance or a writer’s books, it would just keep a record of what they claim to do just as is the case with churches and charities. If there is a question of fraud, the I.R.S. could determine if the individual or organization actually does what they claim.

There would also be a condition that creative workers who receive money through the system don’t have the option of getting copyright protection for a substantial period of time (e.g. 3-5 years). The logic here is that the government only gives creative workers one subsidy, not two. If people choose to get money through the tax credit system, they are not also entitled to a copyright monopoly.

A nice feature of this system is that it is self-enforcing. If someone is getting support through the tax credit system, but then tries to secure a copyright in the period in which they are not eligible, the copyright would be unenforceable. If they attempted to file an infringement suit, the defendant need only point out that the creative worker was in the tax credit system and the case would be immediately dismissed.

This sort of tax credit system could support a huge amount of creative work. If the credit was $100 and 200 million people chose to take advantage of it, that would generate $20 billion a year to support creative workers. A $200 credit would generate $40 billion a year. By comparison, in 2022 the United States spent $16.1 billion on music streaming services.

Of course, there can be no guarantee that everyone who wanted to do creative work would be able to support themselves through this system, just as there is no guarantee under the copyright system. What we can say is that there would be much less money wasted supporting an archaic legal construct and harassing people like Brewster Kahle, the creator of the digital archive at the center of the Streitfield piece.

Streitfield begins his article with the famous line “information wants to be free.” With a system of tax credits to support creative work, it would genuinely be free.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión