That is in effect what Steven Hill argues in his NYT column today. While the column makes many useful points about Uber’s impact on the environment and its treatment of its drivers, the underlying issue is that Uber is hugely subsidizing its rides, causing it to lose $4.5 billion in 2017. Hill proposes that the government either require Uber to raise its fees or that it impose a tax to offset the loss.

While the idea of leveling the playing field is appealing, it is worth asking why a company has a business model that involves losing massive amounts of money. The logic is presumably that Uber expects to drive out competition so that at some point in the future it can jack up its prices and make large profits. Back in the old days, we had something called “anti-trust” policy which would prevent something like this.

If the government treated the anti-trust laws seriously (they are still there), instead of seeking campaign contributions from the biggest violators (e.g. Facebook and Google), Uber’s strategy would make zero sense. The company would be losing large amounts of money today, with the prospect of losing even more in the future as its money-losing business model continued to expand. As we know, investors aren’t always too sharp, but most aren’t willing to throw their money down the toilet forever. (There is a similar story with Amazon, which is barely profitable on the whole and loses money in most of its lines of business.)

The Uber huge loss model only makes sense in a context where people don’t think anti-trust law will be enforced. If we had an administration in Washington that made it very clear that it would not tolerate Uber taking advantage of its market position to jack up prices, the company would likely have to change its practices very quickly or end up in bankruptcy.

That is in effect what Steven Hill argues in his NYT column today. While the column makes many useful points about Uber’s impact on the environment and its treatment of its drivers, the underlying issue is that Uber is hugely subsidizing its rides, causing it to lose $4.5 billion in 2017. Hill proposes that the government either require Uber to raise its fees or that it impose a tax to offset the loss.

While the idea of leveling the playing field is appealing, it is worth asking why a company has a business model that involves losing massive amounts of money. The logic is presumably that Uber expects to drive out competition so that at some point in the future it can jack up its prices and make large profits. Back in the old days, we had something called “anti-trust” policy which would prevent something like this.

If the government treated the anti-trust laws seriously (they are still there), instead of seeking campaign contributions from the biggest violators (e.g. Facebook and Google), Uber’s strategy would make zero sense. The company would be losing large amounts of money today, with the prospect of losing even more in the future as its money-losing business model continued to expand. As we know, investors aren’t always too sharp, but most aren’t willing to throw their money down the toilet forever. (There is a similar story with Amazon, which is barely profitable on the whole and loses money in most of its lines of business.)

The Uber huge loss model only makes sense in a context where people don’t think anti-trust law will be enforced. If we had an administration in Washington that made it very clear that it would not tolerate Uber taking advantage of its market position to jack up prices, the company would likely have to change its practices very quickly or end up in bankruptcy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It said this clearly in a front page article. The piece tells readers how Republicans are falling in line behind Trump’s agenda. After noting that the new budget passed by Congress will lead to a deficit of more than $1 trillion in 2019, the article comments:

“It was another example of how Trump seems to have overtaken his party’s previously understood values, from a willingness to flout free-trade principles and fiscal austerity to a seeming abdication of America’s role as a global voice for democratic values.”

Since this is an economics blog, I’ll leave it to others to speculate how anyone might have understood a party that led the invasion of Iraq under a false pretext to be a global voice for democratic values. I’ll instead focus on the Republican Party’s alleged commitment to “free trade and fiscal austerity.”

I may have missed it, but I never heard a single prominent Republican propose any measure that would reduce the protectionist rules that limit the number of foreign doctors, allowing our doctors to earn twice as much on average as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. This difference in doctors pay costs us $100 billion annually or approximately $800 per household. There is ten times as much money at stake with doctors alone as with the steel tariffs that have gotten so much attention. Protection for other professionals could easily double this number.

No one committed to free trade could find this protectionism acceptable. The “free trade” Republicans have generally supported has been about removing barriers that protect less highly educated workers, putting downward pressure on their pay. That implies a commitment to redistributing income upward (one shared by the Washington Post), not free trade.

The Republican trade agenda also involves making patent and copyright monopolies longer and stronger and spreading these rules internationally. These are incredibly costly forms of protectionism. In the case of prescription drugs alone, patents and related protections add more than $370 billion (almost 2.0 percent of GDP) to what we pay for prescription drugs each year.

The commitment to fiscal austerity is equally absurd. The deficit exploded in the Reagan years due to his tax cuts and increases in military spending. It also exploded under George W. Bush due to his tax cuts and wars. Why on earth would anyone think that the Republican Party had a commitment to fiscal austerity?

So, the take away from this piece is the Washington Post wants its readers to believe that the Republicans had been committed to free trade and fiscal austerity before Trump. That might be true in Washington Postland, where NAFTA caused Mexico’s GDP to quadruple, but not in the real world.

Addendum:

An earlier version had an incorrect number for the per household cost of excess payments to doctors. Thanks to Robert Salzberg for calling my attention to the error.

It said this clearly in a front page article. The piece tells readers how Republicans are falling in line behind Trump’s agenda. After noting that the new budget passed by Congress will lead to a deficit of more than $1 trillion in 2019, the article comments:

“It was another example of how Trump seems to have overtaken his party’s previously understood values, from a willingness to flout free-trade principles and fiscal austerity to a seeming abdication of America’s role as a global voice for democratic values.”

Since this is an economics blog, I’ll leave it to others to speculate how anyone might have understood a party that led the invasion of Iraq under a false pretext to be a global voice for democratic values. I’ll instead focus on the Republican Party’s alleged commitment to “free trade and fiscal austerity.”

I may have missed it, but I never heard a single prominent Republican propose any measure that would reduce the protectionist rules that limit the number of foreign doctors, allowing our doctors to earn twice as much on average as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. This difference in doctors pay costs us $100 billion annually or approximately $800 per household. There is ten times as much money at stake with doctors alone as with the steel tariffs that have gotten so much attention. Protection for other professionals could easily double this number.

No one committed to free trade could find this protectionism acceptable. The “free trade” Republicans have generally supported has been about removing barriers that protect less highly educated workers, putting downward pressure on their pay. That implies a commitment to redistributing income upward (one shared by the Washington Post), not free trade.

The Republican trade agenda also involves making patent and copyright monopolies longer and stronger and spreading these rules internationally. These are incredibly costly forms of protectionism. In the case of prescription drugs alone, patents and related protections add more than $370 billion (almost 2.0 percent of GDP) to what we pay for prescription drugs each year.

The commitment to fiscal austerity is equally absurd. The deficit exploded in the Reagan years due to his tax cuts and increases in military spending. It also exploded under George W. Bush due to his tax cuts and wars. Why on earth would anyone think that the Republican Party had a commitment to fiscal austerity?

So, the take away from this piece is the Washington Post wants its readers to believe that the Republicans had been committed to free trade and fiscal austerity before Trump. That might be true in Washington Postland, where NAFTA caused Mexico’s GDP to quadruple, but not in the real world.

Addendum:

An earlier version had an incorrect number for the per household cost of excess payments to doctors. Thanks to Robert Salzberg for calling my attention to the error.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post might have confused some readers in a piece on how many highly paid professionals are looking to form new S corporations to game the new tax law. Most people who own S corporations will get a 20 percent tax savings on the income they get from these corporations.

At one point the piece told readers:

“Millions of American businesses pay taxes through the individual tax code, known in tax parlance as ‘pass-through’ businesses. [These are S corporations.] They’ve historically done that so they could pay taxes below the 35 percent corporate tax rate, which was reduced to 21 percent in the December tax law.”

This is incorrect. If the businesses were chartered as normal corporations, they would pay the 35 percent corporate tax rate. Then the money paid out to their owner or owners as dividends or as realized capital gains would be taxed as individual income, with a top rate of 20 percent.

Until the change in the tax law, many owners of S corporations were in the top 39.6 percent bracket, so they actually faced a tax rate on their income from S corporations that was higher than the 35 percent corporate tax rate. The advantage of the S-corporation was that it allowed the owners of corporations to escape the corporate income tax, not the lower tax rate.

The separate corporate tax rate was justified by the fact that the government gives corporations special benefits, most importantly limited liability. It was always a voluntary tax in the sense that anyone who did not feel the benefits of corporate status were worth the tax could just form a partnership instead of a corporation. However, the tax law has been changed over the years so that people can now form an S-corporation to get the benefits of corporate status, without having to pay the corporate income tax.

The Washington Post might have confused some readers in a piece on how many highly paid professionals are looking to form new S corporations to game the new tax law. Most people who own S corporations will get a 20 percent tax savings on the income they get from these corporations.

At one point the piece told readers:

“Millions of American businesses pay taxes through the individual tax code, known in tax parlance as ‘pass-through’ businesses. [These are S corporations.] They’ve historically done that so they could pay taxes below the 35 percent corporate tax rate, which was reduced to 21 percent in the December tax law.”

This is incorrect. If the businesses were chartered as normal corporations, they would pay the 35 percent corporate tax rate. Then the money paid out to their owner or owners as dividends or as realized capital gains would be taxed as individual income, with a top rate of 20 percent.

Until the change in the tax law, many owners of S corporations were in the top 39.6 percent bracket, so they actually faced a tax rate on their income from S corporations that was higher than the 35 percent corporate tax rate. The advantage of the S-corporation was that it allowed the owners of corporations to escape the corporate income tax, not the lower tax rate.

The separate corporate tax rate was justified by the fact that the government gives corporations special benefits, most importantly limited liability. It was always a voluntary tax in the sense that anyone who did not feel the benefits of corporate status were worth the tax could just form a partnership instead of a corporation. However, the tax law has been changed over the years so that people can now form an S-corporation to get the benefits of corporate status, without having to pay the corporate income tax.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

If anyone took the rationale for the Republican tax cuts seriously, the key measure is investment. The promise was that lower corporate tax rates would provide a huge incentive for investment, causing the capital stock to increase by roughly one-third over its baseline growth path within a decade.

As I have pointed out, the early numbers were not good. Capital goods orders fell in both December and January. The National Federation of Independent Businesses reports no notable uptick in the investment plans of its members.

The new numbers from the Commerce Department today look a bit better. Overall capital goods orders were up 4.5 percent in February from January levels. If we pull out erratic aircraft orders there was still an increase of 1.8 percent. That’s a pretty good one month jump, but it follows declines in the last two months that totaled 0.9 percent. That leaves growth of 0.9 percent in the last three months or 0.3 percent a month.

The increase over the last year is 7.4 percent. That is roughly the same as the rate of growth before the tax cut. In other words, we’re pretty much on the baseline path, with no obvious tax cut induced jump.

This may not be a great story for tax cut proponents, but at least investment is now moving in the right direction.

If anyone took the rationale for the Republican tax cuts seriously, the key measure is investment. The promise was that lower corporate tax rates would provide a huge incentive for investment, causing the capital stock to increase by roughly one-third over its baseline growth path within a decade.

As I have pointed out, the early numbers were not good. Capital goods orders fell in both December and January. The National Federation of Independent Businesses reports no notable uptick in the investment plans of its members.

The new numbers from the Commerce Department today look a bit better. Overall capital goods orders were up 4.5 percent in February from January levels. If we pull out erratic aircraft orders there was still an increase of 1.8 percent. That’s a pretty good one month jump, but it follows declines in the last two months that totaled 0.9 percent. That leaves growth of 0.9 percent in the last three months or 0.3 percent a month.

The increase over the last year is 7.4 percent. That is roughly the same as the rate of growth before the tax cut. In other words, we’re pretty much on the baseline path, with no obvious tax cut induced jump.

This may not be a great story for tax cut proponents, but at least investment is now moving in the right direction.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is striking how the media universally accept the idea that patent and copyright monopolies are somehow free trade. We get that the people who own and control major news outlets like these forms of protection, but it is incredibly dishonest to claim that they are somehow free trade.

We get this story yet again in an NYT piece complaining about China’s “theft” of intellectual property while telling readers about how Trump’s proposed tariffs show his:

“[…]resolve to turn away from a decades-long move toward open markets and integrated world economies and toward a more starkly protectionist approach that erects barriers around a Fortress America.”

While we are supposed to be alarmed about tariffs of 10 percent and 25 percent on steel and aluminum, patents and copyrights are effectively tariffs of many thousand percents, often raising the price of protected items tenfold or even a hundredfold. The economic impact of increased protectionism of this type has been enormous.

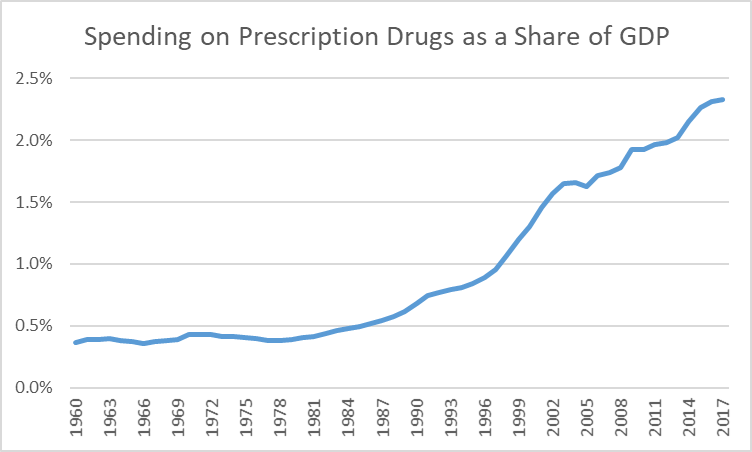

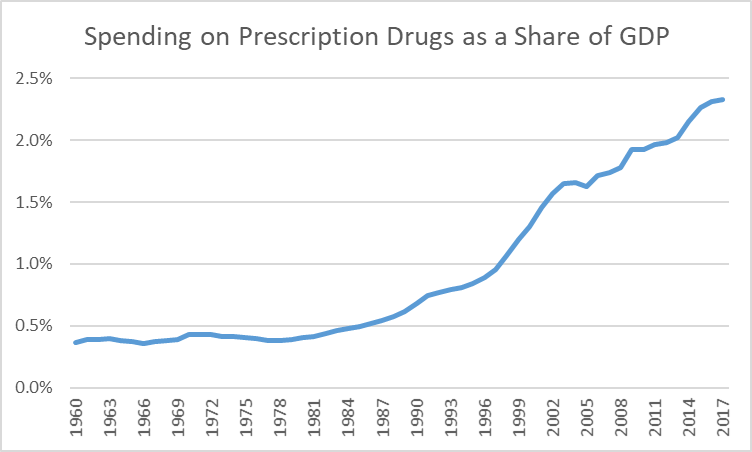

This can be seen clearly in the case of prescription drugs, where spending went from around 0.4 percent of GDP in the 1960s and 1970s to 2.4 percent of GDP ($450 billion) in 2017, as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Since drugs are almost invariably cheap to manufacture, we would likely be spending less than $80 billion a year in the absence of patent and related protections, implying a cost of protectionism of more than $370 billion, and this is just from drug patents. Adding in costs in medical equipment, software, and other areas would likely more than double and quite possibly triple this amount.

The supporters of this protectionism argue that we need patent and copyright monopolies to provide an incentive for innovation and creative work. However, there are two major flaws in this argument.

First, while these monopolies are one way to finance research, they are not the only way. There are other mechanisms, such as direct government funding (we already spend more than $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health). Given the enormous cost associated with this protectionism, it would be reasonable to be debating the relative merits of alternatives. (See also Chapter 5 of Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

The other point is even simpler. We have been making patent and copyright protection stronger and longer for the last four decades. We know that this shifts more money from the rest of us to those who benefit from these protections. Even if we decide that these mechanisms are the best way to finance innovation and creative work, it does not mean that making them stronger and longer is always justified.

We should be asking the question of how much additional innovation or creative work do we get for an increment to strengthen and lengthen. This debate never takes place.

This creates the absurd situation where we put in place policies that are designed to transfer money from the rest of us to people like Bill Gates and then we wonder why we have so much income inequality. And the best part of the story is that some of the big gainers from these protections will even finance research as to why we have so much inequality, as long as it doesn’t ask questions about patent and copyright protection.

It is striking how the media universally accept the idea that patent and copyright monopolies are somehow free trade. We get that the people who own and control major news outlets like these forms of protection, but it is incredibly dishonest to claim that they are somehow free trade.

We get this story yet again in an NYT piece complaining about China’s “theft” of intellectual property while telling readers about how Trump’s proposed tariffs show his:

“[…]resolve to turn away from a decades-long move toward open markets and integrated world economies and toward a more starkly protectionist approach that erects barriers around a Fortress America.”

While we are supposed to be alarmed about tariffs of 10 percent and 25 percent on steel and aluminum, patents and copyrights are effectively tariffs of many thousand percents, often raising the price of protected items tenfold or even a hundredfold. The economic impact of increased protectionism of this type has been enormous.

This can be seen clearly in the case of prescription drugs, where spending went from around 0.4 percent of GDP in the 1960s and 1970s to 2.4 percent of GDP ($450 billion) in 2017, as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Since drugs are almost invariably cheap to manufacture, we would likely be spending less than $80 billion a year in the absence of patent and related protections, implying a cost of protectionism of more than $370 billion, and this is just from drug patents. Adding in costs in medical equipment, software, and other areas would likely more than double and quite possibly triple this amount.

The supporters of this protectionism argue that we need patent and copyright monopolies to provide an incentive for innovation and creative work. However, there are two major flaws in this argument.

First, while these monopolies are one way to finance research, they are not the only way. There are other mechanisms, such as direct government funding (we already spend more than $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health). Given the enormous cost associated with this protectionism, it would be reasonable to be debating the relative merits of alternatives. (See also Chapter 5 of Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

The other point is even simpler. We have been making patent and copyright protection stronger and longer for the last four decades. We know that this shifts more money from the rest of us to those who benefit from these protections. Even if we decide that these mechanisms are the best way to finance innovation and creative work, it does not mean that making them stronger and longer is always justified.

We should be asking the question of how much additional innovation or creative work do we get for an increment to strengthen and lengthen. This debate never takes place.

This creates the absurd situation where we put in place policies that are designed to transfer money from the rest of us to people like Bill Gates and then we wonder why we have so much income inequality. And the best part of the story is that some of the big gainers from these protections will even finance research as to why we have so much inequality, as long as it doesn’t ask questions about patent and copyright protection.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Not deliberately of course, but the NYT had this great piece on how the junk food industry is trying to limit required warnings on junk food as part a renegotiated NAFTA. The issue is that our trading partners are looking to take measures to discourage people from eating foods that are high in sugar, fat, and salt. Several cities and states are considering similar measures. The junk food industry is looking to block such measures by getting a ban included in the new NAFTA.

If you’re wondering what this has to do with free trade, the answer is nothing. However, it is a beautiful example of an industry working to use a trade agreement to subvert the democratic process to advance its interests in a trade deal. If the junk food industry gets its way, the resulting pact will then be blessed as a “free trade” deal. The Washington Post and all the other beacons of the establishment will the proclaim their support for the new NAFTA and denounce opponents as Neanderthal protectionists.

Many of us have long been making the point that recent trade deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership have little to do with trade and are more about locking in place a business-friendly structure of regulation. But it took the clumsy ineptitude of the Trump Administration to remove any veneer. Thank you, President Trump.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for corrections from an earlier version.

Not deliberately of course, but the NYT had this great piece on how the junk food industry is trying to limit required warnings on junk food as part a renegotiated NAFTA. The issue is that our trading partners are looking to take measures to discourage people from eating foods that are high in sugar, fat, and salt. Several cities and states are considering similar measures. The junk food industry is looking to block such measures by getting a ban included in the new NAFTA.

If you’re wondering what this has to do with free trade, the answer is nothing. However, it is a beautiful example of an industry working to use a trade agreement to subvert the democratic process to advance its interests in a trade deal. If the junk food industry gets its way, the resulting pact will then be blessed as a “free trade” deal. The Washington Post and all the other beacons of the establishment will the proclaim their support for the new NAFTA and denounce opponents as Neanderthal protectionists.

Many of us have long been making the point that recent trade deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership have little to do with trade and are more about locking in place a business-friendly structure of regulation. But it took the clumsy ineptitude of the Trump Administration to remove any veneer. Thank you, President Trump.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for corrections from an earlier version.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión