In an article on the effort to renegotiate the terms of NAFTA, the NYT noted the Trump administration’s plan to put in language that would prohibit currency management. (The article uses the term “manipulation,” which implies an action being done in secret. In fact, large-scale efforts to affect the value of a country’s currency will almost always be open, since they are almost impossible to conceal.) The piece then notes that since both Canada and Mexico have freely floated their currencies for decades, this is a “symbolic gesture.”

This is not true. Many people in trade debates have claimed that it is impossible to have currency rules in a trade agreement. They have argued that it is impossible to identify steps to manage currency and distinguish them from the normal conduct of monetary policy. Having solid language on currency management in a revised NAFTA would show that it is possible. Also, since the original NAFTA served as a model for many future trade deals, a currency provision in a revised NAFTA could be the basis for similar provisions in other trade deals.

In an article on the effort to renegotiate the terms of NAFTA, the NYT noted the Trump administration’s plan to put in language that would prohibit currency management. (The article uses the term “manipulation,” which implies an action being done in secret. In fact, large-scale efforts to affect the value of a country’s currency will almost always be open, since they are almost impossible to conceal.) The piece then notes that since both Canada and Mexico have freely floated their currencies for decades, this is a “symbolic gesture.”

This is not true. Many people in trade debates have claimed that it is impossible to have currency rules in a trade agreement. They have argued that it is impossible to identify steps to manage currency and distinguish them from the normal conduct of monetary policy. Having solid language on currency management in a revised NAFTA would show that it is possible. Also, since the original NAFTA served as a model for many future trade deals, a currency provision in a revised NAFTA could be the basis for similar provisions in other trade deals.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a piece discussing Sinclair Broadcasting’s plans for expansion and the apparent green light coming from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). As the piece explains, the FCC is now headed by Ajit V. Pai. Mr. Pai apparently met with David D. Smith, the chairman of Sinclair, just before he became chair. Shortly thereafter, the FCC weakened a rule that may have slowed Sinclair’s plans for expansion.

At one point the piece describes Mr. Pai as “an enthusiastic purveyor of free-market philosophy.”

This is not at all clear from the description of his views in the piece. In a true free market, the government would not be allocating air waves. The assignment of frequencies to specific companies by the government, with the threat of arrest for interfering, is not a free market. This is government intervention.

It is possible to argue that this government intervention is necessary to make the airwaves usable (if dozens of people tried to broadcast on the same frequency, no one would be able to hear or see anything), but people who support the assignment of frequencies are not in favor of a free market. Even if we accept the need to assign frequencies, there are an infinite number of ways this can be done.

A frequency can be parceled out by the hour, with individuals or companies only getting claims to short periods. To broadcast a longer show or movie it would then be necessary to buy up enough slots from others to allow for the necessary time. The slots can also be auctioned off rather than given away for free to private companies. This way, the government, rather than private companies, would benefit from the monopolization of the airwaves.

It is understandable that owners of television and radio stations would like to pretend that they support the free market when they want the government to just turn over exclusive use of frequencies, with no questions asked, but this is not true.

Note: Thanks to Keane Bhatt for calling this to my attention.

The NYT had a piece discussing Sinclair Broadcasting’s plans for expansion and the apparent green light coming from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). As the piece explains, the FCC is now headed by Ajit V. Pai. Mr. Pai apparently met with David D. Smith, the chairman of Sinclair, just before he became chair. Shortly thereafter, the FCC weakened a rule that may have slowed Sinclair’s plans for expansion.

At one point the piece describes Mr. Pai as “an enthusiastic purveyor of free-market philosophy.”

This is not at all clear from the description of his views in the piece. In a true free market, the government would not be allocating air waves. The assignment of frequencies to specific companies by the government, with the threat of arrest for interfering, is not a free market. This is government intervention.

It is possible to argue that this government intervention is necessary to make the airwaves usable (if dozens of people tried to broadcast on the same frequency, no one would be able to hear or see anything), but people who support the assignment of frequencies are not in favor of a free market. Even if we accept the need to assign frequencies, there are an infinite number of ways this can be done.

A frequency can be parceled out by the hour, with individuals or companies only getting claims to short periods. To broadcast a longer show or movie it would then be necessary to buy up enough slots from others to allow for the necessary time. The slots can also be auctioned off rather than given away for free to private companies. This way, the government, rather than private companies, would benefit from the monopolization of the airwaves.

It is understandable that owners of television and radio stations would like to pretend that they support the free market when they want the government to just turn over exclusive use of frequencies, with no questions asked, but this is not true.

Note: Thanks to Keane Bhatt for calling this to my attention.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

When you’re rich and powerful in the United States you get to lie freely to advance your position in public debate, including the opinion page of The New York Times. This is why the paper ran an anti-free trade diatribe against China, insisting that the country respect patent and copyright protections claimed by U.S. companies.

The column, by two former U.S. intelligence officials, asserted:

“Chinese companies, with the encouragement of official Chinese policy and often the active participation of government personnel, have been pillaging the intellectual property of American companies. All together, intellectual-property theft costs America up to $600 billion a year, the greatest transfer of wealth in history. China accounts for most of that loss.”

Hmmm, $600 billion a year? That’s more than 3 percent of U.S. GDP, it’s more than 25 percent of all U.S. exports, it’s roughly 30 times what we spend each year on TANF. Does that make sense?

The column doesn’t give the source for this number, but when the industry groups have come up with these sorts of figures in the past, it is usually by assigning the retail value of their product in the United States to every unauthorized copy everywhere in the world. Let’s say that there are 100 million unauthorized versions of Microsoft Windows in China. (I have no idea if this is a reasonable number.) If the retail price of Windows is $50 a copy, then the industry group writes down $5 billion as the theft, even if most of these people would switch to a decent operating system even if they were just charged a couple of dollars for Windows.

We get the same story for prescription drugs. A generic version of a drug like the Hepatitis C drug Sovaldi may sell for a few hundred dollars in the developing world. Gilead Sciences has a retail price of $84,000. If there are a million treatments in India and elsewhere, this comes to $84 billion in “theft.” We, of course, have to skip the fact that Gilead Sciences doesn’t have clear patent rights to this drug in much of the world. If they say so, it is good enough for the debate and The New York Times.

Anyhow, it is striking that this sort of nonsense is supposed to be treated respectfully by serious people. We expect President Trump and other political figures to go to bat with China and other countries to enforce the claims of Microsoft, Pfizer, and other companies whining about their intellectual “property,” but when it comes to adjusting currency values to address the trade deficit — well, then we are all really wimpy and can’t do anything. After all, that is just about the income of manufacturing workers (you know uneducated people), not the money of people who really matter.

So, there you have it. The folks who matter have a right to expect the president to massively interfere in the internal affairs of China and other countries to make them richer. But, ordinary workers? Well, let’s twiddle our thumbs and pretend to give a damn.

When you’re rich and powerful in the United States you get to lie freely to advance your position in public debate, including the opinion page of The New York Times. This is why the paper ran an anti-free trade diatribe against China, insisting that the country respect patent and copyright protections claimed by U.S. companies.

The column, by two former U.S. intelligence officials, asserted:

“Chinese companies, with the encouragement of official Chinese policy and often the active participation of government personnel, have been pillaging the intellectual property of American companies. All together, intellectual-property theft costs America up to $600 billion a year, the greatest transfer of wealth in history. China accounts for most of that loss.”

Hmmm, $600 billion a year? That’s more than 3 percent of U.S. GDP, it’s more than 25 percent of all U.S. exports, it’s roughly 30 times what we spend each year on TANF. Does that make sense?

The column doesn’t give the source for this number, but when the industry groups have come up with these sorts of figures in the past, it is usually by assigning the retail value of their product in the United States to every unauthorized copy everywhere in the world. Let’s say that there are 100 million unauthorized versions of Microsoft Windows in China. (I have no idea if this is a reasonable number.) If the retail price of Windows is $50 a copy, then the industry group writes down $5 billion as the theft, even if most of these people would switch to a decent operating system even if they were just charged a couple of dollars for Windows.

We get the same story for prescription drugs. A generic version of a drug like the Hepatitis C drug Sovaldi may sell for a few hundred dollars in the developing world. Gilead Sciences has a retail price of $84,000. If there are a million treatments in India and elsewhere, this comes to $84 billion in “theft.” We, of course, have to skip the fact that Gilead Sciences doesn’t have clear patent rights to this drug in much of the world. If they say so, it is good enough for the debate and The New York Times.

Anyhow, it is striking that this sort of nonsense is supposed to be treated respectfully by serious people. We expect President Trump and other political figures to go to bat with China and other countries to enforce the claims of Microsoft, Pfizer, and other companies whining about their intellectual “property,” but when it comes to adjusting currency values to address the trade deficit — well, then we are all really wimpy and can’t do anything. After all, that is just about the income of manufacturing workers (you know uneducated people), not the money of people who really matter.

So, there you have it. The folks who matter have a right to expect the president to massively interfere in the internal affairs of China and other countries to make them richer. But, ordinary workers? Well, let’s twiddle our thumbs and pretend to give a damn.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

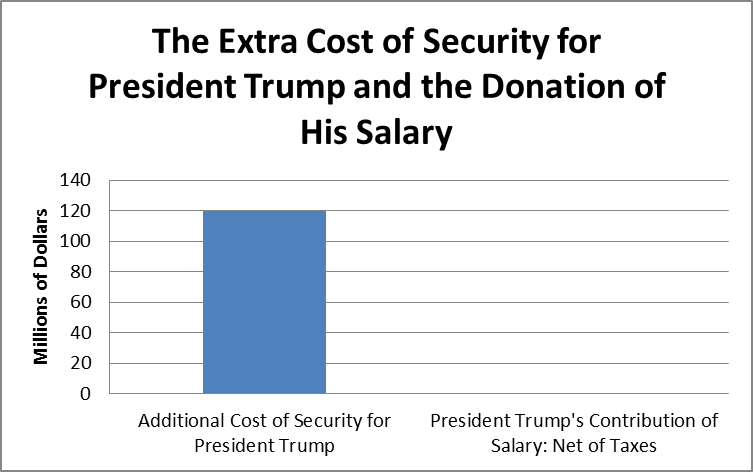

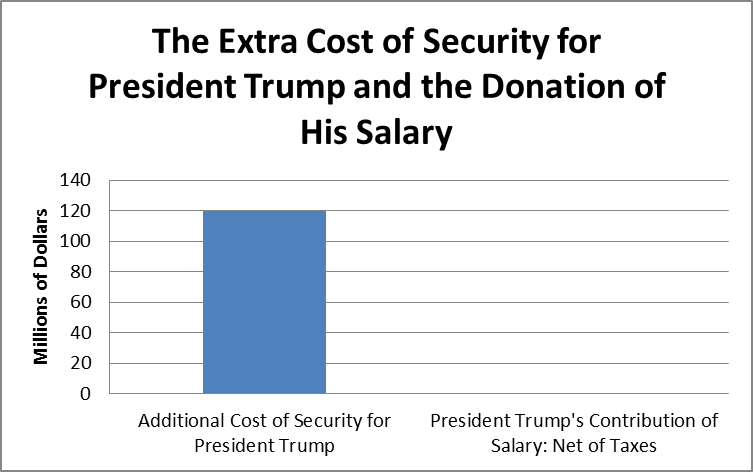

President Trump has made a point of very publicly donating his $400,000 annual salary as president to various civic minded efforts. He recently announced the donation of $100,000 to a camp run by the Department of Education to encourage women to enter science, technology, education, and math. He donated his first quarter’s pay of $100,000 the National Park Service to help pay for the cost of the restoration of the Civil War battlefield at Antietam.

While these contributions will likely support socially useful activities, people should not be misled into thinking the national budget has benefited by having a billionaire business person in the White House. According to the New York Times, Congress had to appropriate an additional $120 million to cover the additional security costs required by Trump as a result of the unusual security demands that he and his family have placed on the Secret Service and government agencies.

To be clear, these are not the normal costs of protecting the president. This $120 million is additional spending that was needed as a result of factors unique to Trump. This includes the Secret Service protection for his adult children (adult children of prior presidents have not been protected), his decision to have his wife and one of his sons stay in New York for the first six months of his presidency, and his habit of visiting Trump properties rather than vacationing at Camp David, like prior presidents. Camp David is already well-secured, and therefore does not require much additional spending when the president visits. This is not the case with Mar-a-Lago and various other Trump properties.

The chart below gives the relative costs of the additional security spending required by the Trump family and the value of his donated salary, net of taxes. (It assumes that he would pay 40 percent of his $400,000 annual salary in taxes.)

Source: New York Times and CNN.

As can be seen, the additional cost of security for President Trump and his family is more than 400 times the net value of the contribution of his presidential paycheck. The public would be considerably better off with a president who pocketed his paycheck and made less extravagant security demands on the Secret Service and other governmental agencies.

President Trump has made a point of very publicly donating his $400,000 annual salary as president to various civic minded efforts. He recently announced the donation of $100,000 to a camp run by the Department of Education to encourage women to enter science, technology, education, and math. He donated his first quarter’s pay of $100,000 the National Park Service to help pay for the cost of the restoration of the Civil War battlefield at Antietam.

While these contributions will likely support socially useful activities, people should not be misled into thinking the national budget has benefited by having a billionaire business person in the White House. According to the New York Times, Congress had to appropriate an additional $120 million to cover the additional security costs required by Trump as a result of the unusual security demands that he and his family have placed on the Secret Service and government agencies.

To be clear, these are not the normal costs of protecting the president. This $120 million is additional spending that was needed as a result of factors unique to Trump. This includes the Secret Service protection for his adult children (adult children of prior presidents have not been protected), his decision to have his wife and one of his sons stay in New York for the first six months of his presidency, and his habit of visiting Trump properties rather than vacationing at Camp David, like prior presidents. Camp David is already well-secured, and therefore does not require much additional spending when the president visits. This is not the case with Mar-a-Lago and various other Trump properties.

The chart below gives the relative costs of the additional security spending required by the Trump family and the value of his donated salary, net of taxes. (It assumes that he would pay 40 percent of his $400,000 annual salary in taxes.)

Source: New York Times and CNN.

As can be seen, the additional cost of security for President Trump and his family is more than 400 times the net value of the contribution of his presidential paycheck. The public would be considerably better off with a president who pocketed his paycheck and made less extravagant security demands on the Secret Service and other governmental agencies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had a column by Ohio attorney general Mike DeWine explaining why he was suing five opioid manufacturers. Dewine explains:

“We believe evidence will show that they flooded the market with prescription opioids, such as OxyContin and Percocet, and grossly misleading information about the risks and benefits of these drugs. And as a result, we believe countless Ohioans and other Americans have become hooked on opioid pain medications, all too often leading to the use of cheaper alternatives such as heroin and synthetic opioids. Almost 80 percent of heroin users start with prescription opioids.”

The incentive to distribute “grossly misleading” information about their products comes from the government-granted patent monopolies which allow companies to charge prices that can be several thousand percent above the free market price. This is straight textbook economics. Corporations are motivated by profit. If they can sell a pill for five dollars that costs them a few cents to manufacture, they have an enormous incentive to market it as widely as possible.

This is a problem with prescription drugs more generally. Manufacturers often exaggerate the effectiveness and safety of their drugs. While it is illegal to knowingly misrepresent the quality of a drug, it is extremely difficult to prove this in court, which means a company has a big incentive to do so. The cost to the public from such misrepresentations is enormous, and unfortunately, it gets very little attention from the media even in the context of the opioid crisis where it is quite obvious.

In the case of opioids, it is true that some of the villains are generic manufacturers. When a drug comes off patent, it is subject to competition. However, even the generics benefit from the high prices that result from patent and related protection. The first generic in a market gets six months of exclusivity, which means that no other generic is allowed to enter the market. Over time more generics will typically enter bringing the price closer to the free market price, but there will be a substantial period in which prices remain inflated, compared to a scenario in which all drugs could be produced as generics on the day they were approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Addendum

Since some folks don’t think the pharmaceutical industry has been deliberately pushing opioids, here a good WaPo piece on the topic.

The Washington Post had a column by Ohio attorney general Mike DeWine explaining why he was suing five opioid manufacturers. Dewine explains:

“We believe evidence will show that they flooded the market with prescription opioids, such as OxyContin and Percocet, and grossly misleading information about the risks and benefits of these drugs. And as a result, we believe countless Ohioans and other Americans have become hooked on opioid pain medications, all too often leading to the use of cheaper alternatives such as heroin and synthetic opioids. Almost 80 percent of heroin users start with prescription opioids.”

The incentive to distribute “grossly misleading” information about their products comes from the government-granted patent monopolies which allow companies to charge prices that can be several thousand percent above the free market price. This is straight textbook economics. Corporations are motivated by profit. If they can sell a pill for five dollars that costs them a few cents to manufacture, they have an enormous incentive to market it as widely as possible.

This is a problem with prescription drugs more generally. Manufacturers often exaggerate the effectiveness and safety of their drugs. While it is illegal to knowingly misrepresent the quality of a drug, it is extremely difficult to prove this in court, which means a company has a big incentive to do so. The cost to the public from such misrepresentations is enormous, and unfortunately, it gets very little attention from the media even in the context of the opioid crisis where it is quite obvious.

In the case of opioids, it is true that some of the villains are generic manufacturers. When a drug comes off patent, it is subject to competition. However, even the generics benefit from the high prices that result from patent and related protection. The first generic in a market gets six months of exclusivity, which means that no other generic is allowed to enter the market. Over time more generics will typically enter bringing the price closer to the free market price, but there will be a substantial period in which prices remain inflated, compared to a scenario in which all drugs could be produced as generics on the day they were approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Addendum

Since some folks don’t think the pharmaceutical industry has been deliberately pushing opioids, here a good WaPo piece on the topic.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I had a blog post a couple of days back in which I argued that rising stock prices reflected expectations of higher future corporate earnings, at least insofar as they were not just driven by irrational exuberance. Since no one seems to be expecting higher growth, the expectation of higher corporate profits presumably means that investors are expecting a redistribution of income away from workers and consumers to corporate profits. This is actually a plausible scenario given Donald Trump’s proposed tax cuts and his plans for changing regulations in ways that will benefit corporations.

This is good news for the 10 percent or so of the population that holds substantial amounts of stock. It is pretty bad news for everyone else. In other words, you probably wouldn’t want to be boasting about a run-up in stock prices unless you think it’s good news to redistribute money from everyone else to the richest 10 percent and especially the richest one percent.

Narayana Kocherlakota, the former president of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve district bank, and a very good economist, disagreed with my assessment. He cited work by John Cochrane arguing that stock market movements could be explained primarily by changes in risk premia. When I questioned whether risk premia had fallen since Trump was elected Kocherlakota tweeted back an index showing the spread between high yield (i.e. risky) corporate bonds and Treasury bonds. This index had indeed fallen since Donald Trump’s election.

Breitbart decided to write up this exchange and expound on how Donald Trump was indeed making America great again and therefore reducing the risk that investors perceived in the economy. The only problem is that they left out my response tweet to Kocherlakota. In this tweet, I pointed out that the spread had just fallen back to its 2014 level.

This matters because if we think this index is a good measure of perceived risk, and if we think risk premia explain movements in the stock market, then we would expect the stock market in 2014 to have been close to its current level and we would have expected sharp declines in 2015 and 2016 as risk premia were rising. Of course, the market was considerably lower in 2014 than it is today. It rose throughout the next two years even as risk premia by this measure were increasing.

That would indicate that a fall in risk premia is not a good explanation of the run-up in stock prices in the last six months. The shift of income from workers and consumers to corporate profits is still the leading candidate.

I had a blog post a couple of days back in which I argued that rising stock prices reflected expectations of higher future corporate earnings, at least insofar as they were not just driven by irrational exuberance. Since no one seems to be expecting higher growth, the expectation of higher corporate profits presumably means that investors are expecting a redistribution of income away from workers and consumers to corporate profits. This is actually a plausible scenario given Donald Trump’s proposed tax cuts and his plans for changing regulations in ways that will benefit corporations.

This is good news for the 10 percent or so of the population that holds substantial amounts of stock. It is pretty bad news for everyone else. In other words, you probably wouldn’t want to be boasting about a run-up in stock prices unless you think it’s good news to redistribute money from everyone else to the richest 10 percent and especially the richest one percent.

Narayana Kocherlakota, the former president of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve district bank, and a very good economist, disagreed with my assessment. He cited work by John Cochrane arguing that stock market movements could be explained primarily by changes in risk premia. When I questioned whether risk premia had fallen since Trump was elected Kocherlakota tweeted back an index showing the spread between high yield (i.e. risky) corporate bonds and Treasury bonds. This index had indeed fallen since Donald Trump’s election.

Breitbart decided to write up this exchange and expound on how Donald Trump was indeed making America great again and therefore reducing the risk that investors perceived in the economy. The only problem is that they left out my response tweet to Kocherlakota. In this tweet, I pointed out that the spread had just fallen back to its 2014 level.

This matters because if we think this index is a good measure of perceived risk, and if we think risk premia explain movements in the stock market, then we would expect the stock market in 2014 to have been close to its current level and we would have expected sharp declines in 2015 and 2016 as risk premia were rising. Of course, the market was considerably lower in 2014 than it is today. It rose throughout the next two years even as risk premia by this measure were increasing.

That would indicate that a fall in risk premia is not a good explanation of the run-up in stock prices in the last six months. The shift of income from workers and consumers to corporate profits is still the leading candidate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión