President Trump has made a point of very publicly donating his $400,000 annual salary as president to various civic minded efforts. He recently announced the donation of $100,000 to a camp run by the Department of Education to encourage women to enter science, technology, education, and math. He donated his first quarter’s pay of $100,000 the National Park Service to help pay for the cost of the restoration of the Civil War battlefield at Antietam.

While these contributions will likely support socially useful activities, people should not be misled into thinking the national budget has benefited by having a billionaire business person in the White House. According to the New York Times, Congress had to appropriate an additional $120 million to cover the additional security costs required by Trump as a result of the unusual security demands that he and his family have placed on the Secret Service and government agencies.

To be clear, these are not the normal costs of protecting the president. This $120 million is additional spending that was needed as a result of factors unique to Trump. This includes the Secret Service protection for his adult children (adult children of prior presidents have not been protected), his decision to have his wife and one of his sons stay in New York for the first six months of his presidency, and his habit of visiting Trump properties rather than vacationing at Camp David, like prior presidents. Camp David is already well-secured, and therefore does not require much additional spending when the president visits. This is not the case with Mar-a-Lago and various other Trump properties.

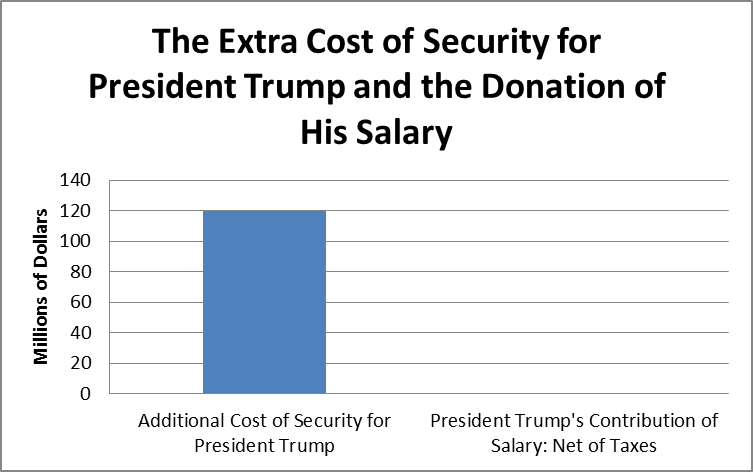

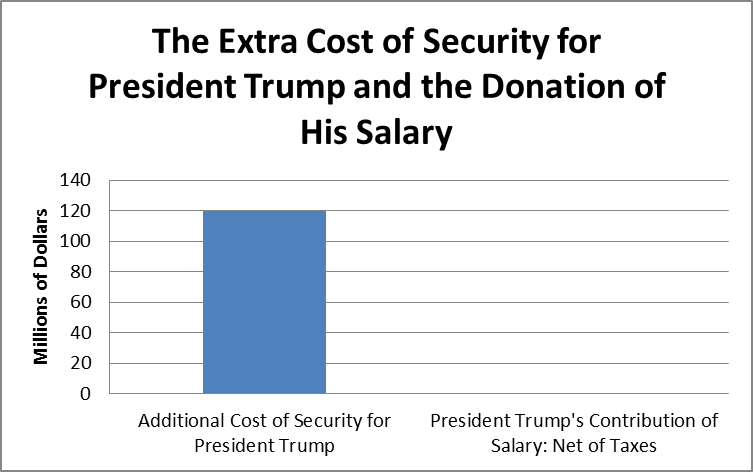

The chart below gives the relative costs of the additional security spending required by the Trump family and the value of his donated salary, net of taxes. (It assumes that he would pay 40 percent of his $400,000 annual salary in taxes.)

Source: New York Times and CNN.

As can be seen, the additional cost of security for President Trump and his family is more than 400 times the net value of the contribution of his presidential paycheck. The public would be considerably better off with a president who pocketed his paycheck and made less extravagant security demands on the Secret Service and other governmental agencies.

President Trump has made a point of very publicly donating his $400,000 annual salary as president to various civic minded efforts. He recently announced the donation of $100,000 to a camp run by the Department of Education to encourage women to enter science, technology, education, and math. He donated his first quarter’s pay of $100,000 the National Park Service to help pay for the cost of the restoration of the Civil War battlefield at Antietam.

While these contributions will likely support socially useful activities, people should not be misled into thinking the national budget has benefited by having a billionaire business person in the White House. According to the New York Times, Congress had to appropriate an additional $120 million to cover the additional security costs required by Trump as a result of the unusual security demands that he and his family have placed on the Secret Service and government agencies.

To be clear, these are not the normal costs of protecting the president. This $120 million is additional spending that was needed as a result of factors unique to Trump. This includes the Secret Service protection for his adult children (adult children of prior presidents have not been protected), his decision to have his wife and one of his sons stay in New York for the first six months of his presidency, and his habit of visiting Trump properties rather than vacationing at Camp David, like prior presidents. Camp David is already well-secured, and therefore does not require much additional spending when the president visits. This is not the case with Mar-a-Lago and various other Trump properties.

The chart below gives the relative costs of the additional security spending required by the Trump family and the value of his donated salary, net of taxes. (It assumes that he would pay 40 percent of his $400,000 annual salary in taxes.)

Source: New York Times and CNN.

As can be seen, the additional cost of security for President Trump and his family is more than 400 times the net value of the contribution of his presidential paycheck. The public would be considerably better off with a president who pocketed his paycheck and made less extravagant security demands on the Secret Service and other governmental agencies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had a column by Ohio attorney general Mike DeWine explaining why he was suing five opioid manufacturers. Dewine explains:

“We believe evidence will show that they flooded the market with prescription opioids, such as OxyContin and Percocet, and grossly misleading information about the risks and benefits of these drugs. And as a result, we believe countless Ohioans and other Americans have become hooked on opioid pain medications, all too often leading to the use of cheaper alternatives such as heroin and synthetic opioids. Almost 80 percent of heroin users start with prescription opioids.”

The incentive to distribute “grossly misleading” information about their products comes from the government-granted patent monopolies which allow companies to charge prices that can be several thousand percent above the free market price. This is straight textbook economics. Corporations are motivated by profit. If they can sell a pill for five dollars that costs them a few cents to manufacture, they have an enormous incentive to market it as widely as possible.

This is a problem with prescription drugs more generally. Manufacturers often exaggerate the effectiveness and safety of their drugs. While it is illegal to knowingly misrepresent the quality of a drug, it is extremely difficult to prove this in court, which means a company has a big incentive to do so. The cost to the public from such misrepresentations is enormous, and unfortunately, it gets very little attention from the media even in the context of the opioid crisis where it is quite obvious.

In the case of opioids, it is true that some of the villains are generic manufacturers. When a drug comes off patent, it is subject to competition. However, even the generics benefit from the high prices that result from patent and related protection. The first generic in a market gets six months of exclusivity, which means that no other generic is allowed to enter the market. Over time more generics will typically enter bringing the price closer to the free market price, but there will be a substantial period in which prices remain inflated, compared to a scenario in which all drugs could be produced as generics on the day they were approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Addendum

Since some folks don’t think the pharmaceutical industry has been deliberately pushing opioids, here a good WaPo piece on the topic.

The Washington Post had a column by Ohio attorney general Mike DeWine explaining why he was suing five opioid manufacturers. Dewine explains:

“We believe evidence will show that they flooded the market with prescription opioids, such as OxyContin and Percocet, and grossly misleading information about the risks and benefits of these drugs. And as a result, we believe countless Ohioans and other Americans have become hooked on opioid pain medications, all too often leading to the use of cheaper alternatives such as heroin and synthetic opioids. Almost 80 percent of heroin users start with prescription opioids.”

The incentive to distribute “grossly misleading” information about their products comes from the government-granted patent monopolies which allow companies to charge prices that can be several thousand percent above the free market price. This is straight textbook economics. Corporations are motivated by profit. If they can sell a pill for five dollars that costs them a few cents to manufacture, they have an enormous incentive to market it as widely as possible.

This is a problem with prescription drugs more generally. Manufacturers often exaggerate the effectiveness and safety of their drugs. While it is illegal to knowingly misrepresent the quality of a drug, it is extremely difficult to prove this in court, which means a company has a big incentive to do so. The cost to the public from such misrepresentations is enormous, and unfortunately, it gets very little attention from the media even in the context of the opioid crisis where it is quite obvious.

In the case of opioids, it is true that some of the villains are generic manufacturers. When a drug comes off patent, it is subject to competition. However, even the generics benefit from the high prices that result from patent and related protection. The first generic in a market gets six months of exclusivity, which means that no other generic is allowed to enter the market. Over time more generics will typically enter bringing the price closer to the free market price, but there will be a substantial period in which prices remain inflated, compared to a scenario in which all drugs could be produced as generics on the day they were approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Addendum

Since some folks don’t think the pharmaceutical industry has been deliberately pushing opioids, here a good WaPo piece on the topic.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I had a blog post a couple of days back in which I argued that rising stock prices reflected expectations of higher future corporate earnings, at least insofar as they were not just driven by irrational exuberance. Since no one seems to be expecting higher growth, the expectation of higher corporate profits presumably means that investors are expecting a redistribution of income away from workers and consumers to corporate profits. This is actually a plausible scenario given Donald Trump’s proposed tax cuts and his plans for changing regulations in ways that will benefit corporations.

This is good news for the 10 percent or so of the population that holds substantial amounts of stock. It is pretty bad news for everyone else. In other words, you probably wouldn’t want to be boasting about a run-up in stock prices unless you think it’s good news to redistribute money from everyone else to the richest 10 percent and especially the richest one percent.

Narayana Kocherlakota, the former president of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve district bank, and a very good economist, disagreed with my assessment. He cited work by John Cochrane arguing that stock market movements could be explained primarily by changes in risk premia. When I questioned whether risk premia had fallen since Trump was elected Kocherlakota tweeted back an index showing the spread between high yield (i.e. risky) corporate bonds and Treasury bonds. This index had indeed fallen since Donald Trump’s election.

Breitbart decided to write up this exchange and expound on how Donald Trump was indeed making America great again and therefore reducing the risk that investors perceived in the economy. The only problem is that they left out my response tweet to Kocherlakota. In this tweet, I pointed out that the spread had just fallen back to its 2014 level.

This matters because if we think this index is a good measure of perceived risk, and if we think risk premia explain movements in the stock market, then we would expect the stock market in 2014 to have been close to its current level and we would have expected sharp declines in 2015 and 2016 as risk premia were rising. Of course, the market was considerably lower in 2014 than it is today. It rose throughout the next two years even as risk premia by this measure were increasing.

That would indicate that a fall in risk premia is not a good explanation of the run-up in stock prices in the last six months. The shift of income from workers and consumers to corporate profits is still the leading candidate.

I had a blog post a couple of days back in which I argued that rising stock prices reflected expectations of higher future corporate earnings, at least insofar as they were not just driven by irrational exuberance. Since no one seems to be expecting higher growth, the expectation of higher corporate profits presumably means that investors are expecting a redistribution of income away from workers and consumers to corporate profits. This is actually a plausible scenario given Donald Trump’s proposed tax cuts and his plans for changing regulations in ways that will benefit corporations.

This is good news for the 10 percent or so of the population that holds substantial amounts of stock. It is pretty bad news for everyone else. In other words, you probably wouldn’t want to be boasting about a run-up in stock prices unless you think it’s good news to redistribute money from everyone else to the richest 10 percent and especially the richest one percent.

Narayana Kocherlakota, the former president of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve district bank, and a very good economist, disagreed with my assessment. He cited work by John Cochrane arguing that stock market movements could be explained primarily by changes in risk premia. When I questioned whether risk premia had fallen since Trump was elected Kocherlakota tweeted back an index showing the spread between high yield (i.e. risky) corporate bonds and Treasury bonds. This index had indeed fallen since Donald Trump’s election.

Breitbart decided to write up this exchange and expound on how Donald Trump was indeed making America great again and therefore reducing the risk that investors perceived in the economy. The only problem is that they left out my response tweet to Kocherlakota. In this tweet, I pointed out that the spread had just fallen back to its 2014 level.

This matters because if we think this index is a good measure of perceived risk, and if we think risk premia explain movements in the stock market, then we would expect the stock market in 2014 to have been close to its current level and we would have expected sharp declines in 2015 and 2016 as risk premia were rising. Of course, the market was considerably lower in 2014 than it is today. It rose throughout the next two years even as risk premia by this measure were increasing.

That would indicate that a fall in risk premia is not a good explanation of the run-up in stock prices in the last six months. The shift of income from workers and consumers to corporate profits is still the leading candidate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Since several people have asked, I thought I would do some recycling. My plan (which I know I have stolen from someone) is to require companies to turn over an amount of stock, in the form of non-voting shares, roughly equal to the targeted tax rate. This means if we’re shooting for a 28 percent tax rate, then the shares going to the government are equal to 28 percent of the total. If the target is 20 percent, then the government’s shares are equal to 20 percent of the total.

From that point forward the government’s shares are treated the same as the other shares of the company. If the company pays a $2 per share dividend, the government gets $2 for each of its shares. If the company buys back 10 percent of its shares at $100 a share, it buys back 10 percent of the government’s shares at $100 per share. A company taking over the company at a $120 per share price has to also pay the government $120 per share. The basic story is that there is no way to cheat the government out of its tax revenue unless the corporation’s management is also cheating its shareholders.

To be as clear as possible, this is not a government takeover of corporate America. As it stands now, the government makes a claim on corporate profits in the form of income taxes. This just changes the form of this claim on profits.

Some folks may want the government to run the whole economy. I don’t. I value having firms compete in the market. This tax proposal doesn’t change that story. In fact, it has the nice feature that companies will no longer make decisions with an eye toward reducing their tax liability, since the only way they can do that is by screwing shareholders. Instead, companies will make decisions that maximize their expected profits.

I should also point out that this can be done on a voluntary basis. Wherever the tax rate is set, companies can be given the option of issuing stock in the same amount (e.g. a 25 percent tax rate means 25 percent of shares). This would have the advantage from the company’s perspective of ending the need to file tax returns. They just pay the government what they are paying shareholders.

From the government’s standpoint it reduces the enforcement costs. The companies that go this route will require minimal enforcement resources. Meanwhile, the companies that don’t opt to go this route will be telling the I.R.S. that they think they can reduce their tax liability substantially below the official rate. The I.R.S. can then focus its resources on policing these companies. That might not be as good as requiring all companies to go the stock route, but it would be a big step forward in my view.

Here are a couple of columns making the argument. Sorry, I’ve never written a longer piece making the case.

Since several people have asked, I thought I would do some recycling. My plan (which I know I have stolen from someone) is to require companies to turn over an amount of stock, in the form of non-voting shares, roughly equal to the targeted tax rate. This means if we’re shooting for a 28 percent tax rate, then the shares going to the government are equal to 28 percent of the total. If the target is 20 percent, then the government’s shares are equal to 20 percent of the total.

From that point forward the government’s shares are treated the same as the other shares of the company. If the company pays a $2 per share dividend, the government gets $2 for each of its shares. If the company buys back 10 percent of its shares at $100 a share, it buys back 10 percent of the government’s shares at $100 per share. A company taking over the company at a $120 per share price has to also pay the government $120 per share. The basic story is that there is no way to cheat the government out of its tax revenue unless the corporation’s management is also cheating its shareholders.

To be as clear as possible, this is not a government takeover of corporate America. As it stands now, the government makes a claim on corporate profits in the form of income taxes. This just changes the form of this claim on profits.

Some folks may want the government to run the whole economy. I don’t. I value having firms compete in the market. This tax proposal doesn’t change that story. In fact, it has the nice feature that companies will no longer make decisions with an eye toward reducing their tax liability, since the only way they can do that is by screwing shareholders. Instead, companies will make decisions that maximize their expected profits.

I should also point out that this can be done on a voluntary basis. Wherever the tax rate is set, companies can be given the option of issuing stock in the same amount (e.g. a 25 percent tax rate means 25 percent of shares). This would have the advantage from the company’s perspective of ending the need to file tax returns. They just pay the government what they are paying shareholders.

From the government’s standpoint it reduces the enforcement costs. The companies that go this route will require minimal enforcement resources. Meanwhile, the companies that don’t opt to go this route will be telling the I.R.S. that they think they can reduce their tax liability substantially below the official rate. The I.R.S. can then focus its resources on policing these companies. That might not be as good as requiring all companies to go the stock route, but it would be a big step forward in my view.

Here are a couple of columns making the argument. Sorry, I’ve never written a longer piece making the case.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Donald Trump has been anxious to take credit for the sharp run-up in stock prices since his election. While it is not clear that anything really lies behind this run-up (remember Wall Street investors are the same folks who thought AOL.com was worth $250 billion back in 2001 and that subprime mortgage backed securities were perfectly safe assets), in principle, stock prices are supposed to represent the present value of future corporate profits. If we assume that the rise in stock prices actually reflect something in the world, and not just Wall Street fantasies, then Trump has given these companies a reason to expect larger future profits.

Profits can rise for two reasons. Either they can be the same share of a larger economic pie or they can be a larger share of the same economic pie. There is no reason to believe that anyone is now expecting faster economic growth than before the election. In fact, the I.M.F. recently cut its growth projection for the U.S. If nothing Trump has done or given any indication of doing is likely to boost the U.S. growth rate then the higher expected profits must mean that investors anticipate that corporations will have a larger share of the economic pie.

There are several paths through which Trump’s policies could have this effect. Most obviously, he has called for sharp reductions in the corporate tax rate. If his tax cuts go through, then after-tax corporate profits will be higher even if there is no change in before-tax profits.

A second route for higher corporate profits is by facilitating rip-offs of consumers. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) was set up in large part to prevent predatory practices by the financial industry. For example, it has sought to make it more difficult for financial firms to slip conditions into contracts that no one would ever agree to if they understood them.

If the CFPB is prevented from protecting consumers then we can assume that financial firms will put more effort into ripping off their customers. This will actually reduce growth since the resources spent writing deceptive contracts could have otherwise been devoted to productive uses.

Another route in which corporate profits can be increased is by letting them destroy the environment at zero cost. For example, the Trump administration reversed an Obama administration executive order that required mining companies to restore hilltops after they did surface mining. By allowing these companies to mine areas without repairing the damage the Trump administration is saving them money. The people in the communities will suffer the consequences in the form of polluted streams and ruined forests, but this is still good news for corporate profits.

Lastly, Trump’s regulatory changes might shift money from wages to profits. The most obvious example here is the plan to reverse the Obama administration’s rule raising the cap under which salaried workers are automatically entitled to overtime pay. By allowing employers to require salaried workers to put in more than 40 hours a week, often without any additional pay, the Trump administration will be putting downward pressure on wages and boosting corporate profits.

For these reasons, investors might have some real cause for expecting higher corporate profits as a result of the Trump presidency. However, none of these reasons are good news for the 90 percent of the country that does not have substantial stock holdings.

Donald Trump has been anxious to take credit for the sharp run-up in stock prices since his election. While it is not clear that anything really lies behind this run-up (remember Wall Street investors are the same folks who thought AOL.com was worth $250 billion back in 2001 and that subprime mortgage backed securities were perfectly safe assets), in principle, stock prices are supposed to represent the present value of future corporate profits. If we assume that the rise in stock prices actually reflect something in the world, and not just Wall Street fantasies, then Trump has given these companies a reason to expect larger future profits.

Profits can rise for two reasons. Either they can be the same share of a larger economic pie or they can be a larger share of the same economic pie. There is no reason to believe that anyone is now expecting faster economic growth than before the election. In fact, the I.M.F. recently cut its growth projection for the U.S. If nothing Trump has done or given any indication of doing is likely to boost the U.S. growth rate then the higher expected profits must mean that investors anticipate that corporations will have a larger share of the economic pie.

There are several paths through which Trump’s policies could have this effect. Most obviously, he has called for sharp reductions in the corporate tax rate. If his tax cuts go through, then after-tax corporate profits will be higher even if there is no change in before-tax profits.

A second route for higher corporate profits is by facilitating rip-offs of consumers. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) was set up in large part to prevent predatory practices by the financial industry. For example, it has sought to make it more difficult for financial firms to slip conditions into contracts that no one would ever agree to if they understood them.

If the CFPB is prevented from protecting consumers then we can assume that financial firms will put more effort into ripping off their customers. This will actually reduce growth since the resources spent writing deceptive contracts could have otherwise been devoted to productive uses.

Another route in which corporate profits can be increased is by letting them destroy the environment at zero cost. For example, the Trump administration reversed an Obama administration executive order that required mining companies to restore hilltops after they did surface mining. By allowing these companies to mine areas without repairing the damage the Trump administration is saving them money. The people in the communities will suffer the consequences in the form of polluted streams and ruined forests, but this is still good news for corporate profits.

Lastly, Trump’s regulatory changes might shift money from wages to profits. The most obvious example here is the plan to reverse the Obama administration’s rule raising the cap under which salaried workers are automatically entitled to overtime pay. By allowing employers to require salaried workers to put in more than 40 hours a week, often without any additional pay, the Trump administration will be putting downward pressure on wages and boosting corporate profits.

For these reasons, investors might have some real cause for expecting higher corporate profits as a result of the Trump presidency. However, none of these reasons are good news for the 90 percent of the country that does not have substantial stock holdings.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Politico gets into the act telling readers how tragic the demise of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is for the rural economy in a special report. Here’s the punch line:

“But for the already struggling agricultural sector, the sprawling 12-nation TPP, covering 40 percent of the world’s economy, was a lifeline. It was a chance to erase punishing tariffs that restricted the United States—the onetime ‘breadbasket of the world’—from selling its meats, grains and dairy products to massive importers of foodstuffs such as Japan and Vietnam.

“The decision to pull out of the trade deal has become a double hit on places like Eagle Grove. The promised bump of $10 billion in agricultural output over 15 years, based on estimates by the U.S. International Trade Commission, won’t materialize. But Trump’s decision to withdraw from the pact also cleared the way for rival exporters such as Australia, New Zealand and the European Union to negotiate even lower tariffs with importing nations, creating potentially greater competitive advantages over U.S. exports.”

Wow, we could have had another $10 billion in agricultural output after 15 years, if only Donald Trump had not pulled the plug. Hmm, $10 billion in additional agricultural output in 2032, is that a big deal?

Well, if we turn to the International Trade Commission (ITC) report cited in the piece, we see that it amounts to 0.5 percent of projected agricultural output in 2032. That’s about equal to six months of normal growth of the agricultural economy. This means that, according to the ITC report, with the TPP in effect, the agricultural economy would be producing roughly as much on January 1, 2032 as it would otherwise be producing on July 1, 2032 without the TPP.

Is this a “lifeline” for the agricultural economy?

There is also reason to be wary of the ITC report, since these models have been incredibly bad at predicting the outcome of past trade deals.

It’s also worth commenting on the apparent horror with which Politico views the possibility, “rival exporters such as Australia, New Zealand and the European Union to negotiate even lower tariffs with importing nations.” In the good old days, economists used to believe that the United States was helped by stronger trading partners. This was one reason the U.S. generally supported the process of economic integration that led to the European Union.

If other countries remove barriers between them, this could make some of their goods better positioned relative to U.S. exports, but it can also lead to more rapid growth in these countries, which will increase demand for U.S. exports. While both effects are likely to be small relative to the size of U.S. production, it is entirely possible that the growth effect will exceed the substitution effect. Long and short, there is no need for reasonable people to be terrified by the prospect of other countries crafting trade deals.

Politico gets into the act telling readers how tragic the demise of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is for the rural economy in a special report. Here’s the punch line:

“But for the already struggling agricultural sector, the sprawling 12-nation TPP, covering 40 percent of the world’s economy, was a lifeline. It was a chance to erase punishing tariffs that restricted the United States—the onetime ‘breadbasket of the world’—from selling its meats, grains and dairy products to massive importers of foodstuffs such as Japan and Vietnam.

“The decision to pull out of the trade deal has become a double hit on places like Eagle Grove. The promised bump of $10 billion in agricultural output over 15 years, based on estimates by the U.S. International Trade Commission, won’t materialize. But Trump’s decision to withdraw from the pact also cleared the way for rival exporters such as Australia, New Zealand and the European Union to negotiate even lower tariffs with importing nations, creating potentially greater competitive advantages over U.S. exports.”

Wow, we could have had another $10 billion in agricultural output after 15 years, if only Donald Trump had not pulled the plug. Hmm, $10 billion in additional agricultural output in 2032, is that a big deal?

Well, if we turn to the International Trade Commission (ITC) report cited in the piece, we see that it amounts to 0.5 percent of projected agricultural output in 2032. That’s about equal to six months of normal growth of the agricultural economy. This means that, according to the ITC report, with the TPP in effect, the agricultural economy would be producing roughly as much on January 1, 2032 as it would otherwise be producing on July 1, 2032 without the TPP.

Is this a “lifeline” for the agricultural economy?

There is also reason to be wary of the ITC report, since these models have been incredibly bad at predicting the outcome of past trade deals.

It’s also worth commenting on the apparent horror with which Politico views the possibility, “rival exporters such as Australia, New Zealand and the European Union to negotiate even lower tariffs with importing nations.” In the good old days, economists used to believe that the United States was helped by stronger trading partners. This was one reason the U.S. generally supported the process of economic integration that led to the European Union.

If other countries remove barriers between them, this could make some of their goods better positioned relative to U.S. exports, but it can also lead to more rapid growth in these countries, which will increase demand for U.S. exports. While both effects are likely to be small relative to the size of U.S. production, it is entirely possible that the growth effect will exceed the substitution effect. Long and short, there is no need for reasonable people to be terrified by the prospect of other countries crafting trade deals.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is strange how the media often respond to the prospects of tariffs on imports by pointing to foreign-owned factories in the United States, implying that these are somehow at risk if tariffs are imposed. The NYT gives us an example of this reporting today in a front page article.

The piece highlights a number of foreign-owned factories in the United States and includes data on foreign direct investment by country and also employment levels. It also includes the warning:

“But political and business leaders here in Hamilton County, a conservative stronghold where Donald J. Trump won a majority of the votes, worry that the president’s attacks on trading partners and exhortations to ‘Buy American’ could set off a protectionist spiral of tariffs and import restrictions, hurting consumers and workers.”

This seems to be a non-sequitur. Tariffs on imports increase the incentive for foreign companies to invest in the United States. They allow them to produce for the U.S. market and get around any tariffs. The first Japanese auto factories in the United States were a direct response to the “voluntary export restraints” on the major Japanese manufacturers agreed to in the Reagan years. The cars that Toyota and other companies produced in the United States did not count against these limits.

There are good arguments to be made against putting up import tariffs, but the idea that it would somehow hurt foreign direct investment in the United States is not one of them. If new tariffs are put in place, it would more likely increase foreign investment than reduce it.

It is strange how the media often respond to the prospects of tariffs on imports by pointing to foreign-owned factories in the United States, implying that these are somehow at risk if tariffs are imposed. The NYT gives us an example of this reporting today in a front page article.

The piece highlights a number of foreign-owned factories in the United States and includes data on foreign direct investment by country and also employment levels. It also includes the warning:

“But political and business leaders here in Hamilton County, a conservative stronghold where Donald J. Trump won a majority of the votes, worry that the president’s attacks on trading partners and exhortations to ‘Buy American’ could set off a protectionist spiral of tariffs and import restrictions, hurting consumers and workers.”

This seems to be a non-sequitur. Tariffs on imports increase the incentive for foreign companies to invest in the United States. They allow them to produce for the U.S. market and get around any tariffs. The first Japanese auto factories in the United States were a direct response to the “voluntary export restraints” on the major Japanese manufacturers agreed to in the Reagan years. The cars that Toyota and other companies produced in the United States did not count against these limits.

There are good arguments to be made against putting up import tariffs, but the idea that it would somehow hurt foreign direct investment in the United States is not one of them. If new tariffs are put in place, it would more likely increase foreign investment than reduce it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión