Most economists would probably agree that a tax reform that cleaned up loopholes could provide a boost to growth. Most would probably also agree that the 1986 tax reform was more good than bad in this respect. (Lowering the top individual tax rate to 28 percent would fall in the “bad” category for many of us.) But it is unlikely that many would endorse the claim in James B. Stewart’s column that after the tax reform:

“The economy (and the stock market) soared.”

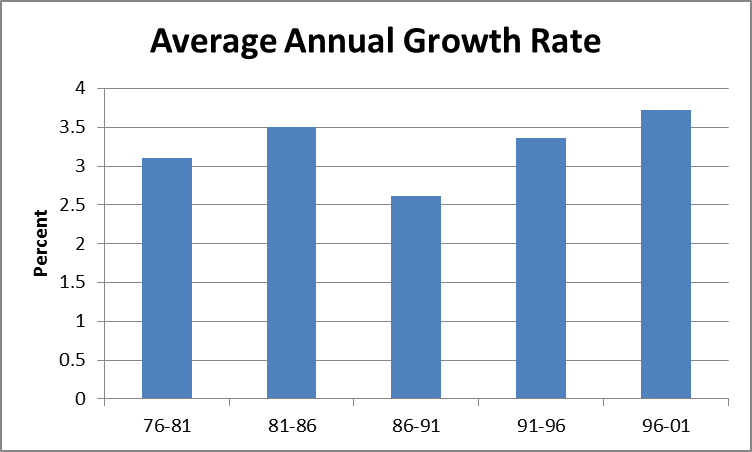

This one is clearly wrong. Growth in the five years following the passage of the tax cut was considerably worse than in the ten years preceding it or the next ten years as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Growth in the five years following the tax reform averaged just 2.6 percent. That compares to 3.5 percent in the five years preceding the reform and 3.4 percent in the subsequent five years. It accelerated to 3.7 percent in the next five year period. I suppose some folks may want to claim the late 1990s boom was due to the 1986 tax reform, but the price of that sort of delayed effect means that the Johnson-Nixon administrations deserve credit for the 1980s growth and the current weak growth should be laid at the doorstep of George W. Bush.

There are of course complicating factors and the tax reform could have been a boost to growth that was offset by other factors, but the simple claim that we cut taxes and the economy boomed is clearly not true.

Most economists would probably agree that a tax reform that cleaned up loopholes could provide a boost to growth. Most would probably also agree that the 1986 tax reform was more good than bad in this respect. (Lowering the top individual tax rate to 28 percent would fall in the “bad” category for many of us.) But it is unlikely that many would endorse the claim in James B. Stewart’s column that after the tax reform:

“The economy (and the stock market) soared.”

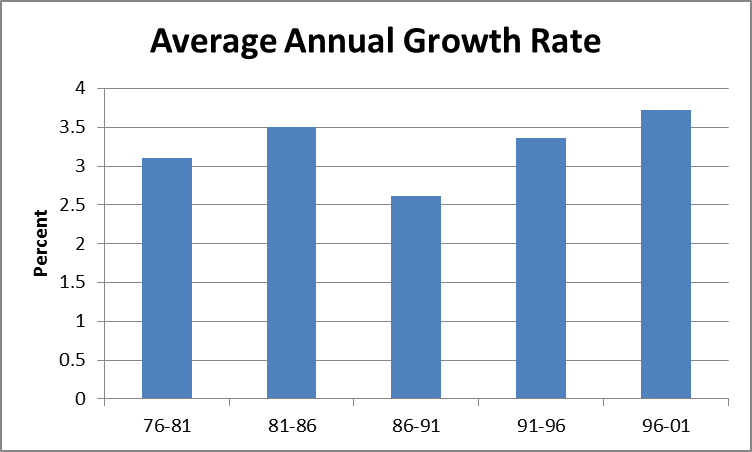

This one is clearly wrong. Growth in the five years following the passage of the tax cut was considerably worse than in the ten years preceding it or the next ten years as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Growth in the five years following the tax reform averaged just 2.6 percent. That compares to 3.5 percent in the five years preceding the reform and 3.4 percent in the subsequent five years. It accelerated to 3.7 percent in the next five year period. I suppose some folks may want to claim the late 1990s boom was due to the 1986 tax reform, but the price of that sort of delayed effect means that the Johnson-Nixon administrations deserve credit for the 1980s growth and the current weak growth should be laid at the doorstep of George W. Bush.

There are of course complicating factors and the tax reform could have been a boost to growth that was offset by other factors, but the simple claim that we cut taxes and the economy boomed is clearly not true.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It would have been useful if the NYT had clarified the strategy being proposed by President Trump and Republicans in this piece headlined “‘let Obamacare fail,’ Trump says as G.O.P. health bill collapses.” There is no reason to think that Obamacare as written into law with the Affordable Care Act would fail. The exchanges are actually working pretty well in the states with Democratic governors committed to making the law work. The problem of insurers dropping out of the exchanges leaving no competition is overwhelmingly a red state problem where Republican politicians have sought to sabotage the program.

It is also worth noting that often repeated claim that the system is suffering badly from a lack of young healthy people signing up, as implied by this Washington Post editorial, is badly confused. The number of uninsured has actually fallen by more than the Congressional Budget Office projected, so there is no story of a massive problem of people not signing up for insurance. There is a problem that more people are still on employer provided insurance and not in the exchanges. Since these people are relatively healthy (they are mostly working full time and many are older, meaning they would pay higher premiums), their loss to the exchanges may be an issue.

However, the arithmetic shows that more young healthy people signing up could not make that much difference to the program. Suppose another 2 million overwhelmingly healthy people signed up for the exchanges. This would be a massive increase, since there are probably not much more than 2 million young healthy people who are not currently insured. (They have to also be citizens or legal residents to qualify.) The average premium for a bronze plan (presumably what healthy people who don’t really want insurance would buy) is $2,700 a year. If we assume that insurers would pocket half of this money as profit, that comes to a net gain to insurers of $2.7 billion a year.

We are supposed to believe this is what determines whether Obamacare sinks or floats?

It would have been useful if the NYT had clarified the strategy being proposed by President Trump and Republicans in this piece headlined “‘let Obamacare fail,’ Trump says as G.O.P. health bill collapses.” There is no reason to think that Obamacare as written into law with the Affordable Care Act would fail. The exchanges are actually working pretty well in the states with Democratic governors committed to making the law work. The problem of insurers dropping out of the exchanges leaving no competition is overwhelmingly a red state problem where Republican politicians have sought to sabotage the program.

It is also worth noting that often repeated claim that the system is suffering badly from a lack of young healthy people signing up, as implied by this Washington Post editorial, is badly confused. The number of uninsured has actually fallen by more than the Congressional Budget Office projected, so there is no story of a massive problem of people not signing up for insurance. There is a problem that more people are still on employer provided insurance and not in the exchanges. Since these people are relatively healthy (they are mostly working full time and many are older, meaning they would pay higher premiums), their loss to the exchanges may be an issue.

However, the arithmetic shows that more young healthy people signing up could not make that much difference to the program. Suppose another 2 million overwhelmingly healthy people signed up for the exchanges. This would be a massive increase, since there are probably not much more than 2 million young healthy people who are not currently insured. (They have to also be citizens or legal residents to qualify.) The average premium for a bronze plan (presumably what healthy people who don’t really want insurance would buy) is $2,700 a year. If we assume that insurers would pocket half of this money as profit, that comes to a net gain to insurers of $2.7 billion a year.

We are supposed to believe this is what determines whether Obamacare sinks or floats?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A news analysis in the NYT by Jennifer Steinhauer argued that Republicans were rediscovering an old truth in their effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act, that it is hard to take away benefits that the government has given. While the point is surely right, the piece left out an important point, the Republican effort was based on a lie.

Republicans, and especially President Trump, rallied public support for repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) based on the complaint that it wasn’t generous enough. They argued that the premiums and deductibles were too high, their plan would give people better insurance.

This was a complete lie, but many people who had legitimate complaints about ACA likely backed Trump and other Republicans with the expectation that they would give them better insurance. Since this is clearly the opposite of what repeal is about, it makes it especially difficult for the Republicans to tell the people who voted for them expecting better insurance that they will have to pay much more money for worse insurance.

This is the situation the Republicans now find themselves in. Essentially, they have to own up to the fact that they have been lying for seven years about the central item on their political agenda.

A news analysis in the NYT by Jennifer Steinhauer argued that Republicans were rediscovering an old truth in their effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act, that it is hard to take away benefits that the government has given. While the point is surely right, the piece left out an important point, the Republican effort was based on a lie.

Republicans, and especially President Trump, rallied public support for repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) based on the complaint that it wasn’t generous enough. They argued that the premiums and deductibles were too high, their plan would give people better insurance.

This was a complete lie, but many people who had legitimate complaints about ACA likely backed Trump and other Republicans with the expectation that they would give them better insurance. Since this is clearly the opposite of what repeal is about, it makes it especially difficult for the Republicans to tell the people who voted for them expecting better insurance that they will have to pay much more money for worse insurance.

This is the situation the Republicans now find themselves in. Essentially, they have to own up to the fact that they have been lying for seven years about the central item on their political agenda.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I have often joked how when we have a political debate after we watch the candidates stake out various claims and positions, we then see reporters talk about their body language. They tell us who looked confident and sincere and who seemed cautious or in other ways unsteady.

This is infuriating because this is exactly the area in which reporters have no comparative advantage over the people viewing the debate. We all engage in conversations and negotiations with people in our everyday life. Most of us are used to assessing the sincerity and integrity of the people we deal with. When we are watching politicians put forward their case on television we can all judge their sincerity and confidence. There is no particular reason to believe that the reporters giving their commentary can do a better job at this than the rest of the people watching the debate.

On the other hand, the reporters could, in principle, know more about the truth of the politicians’ claims. They could know about the background to their policy proposals, where they have been tried, and the issues that have been raised by various experts. Reporters almost invariably fail to provide this sort of analysis, which would be a useful service to their audience.

Anyhow, we got a full and explicit example of the body language treatment this morning on National Public Radio. Their discussion of the meeting between French President Emmanuel Macron and Donald Trump explicitly focused on the body language between the two leaders and assured us that they have struck up a genuine friendship.

I didn’t have a chance to see the events on television, but let me record my skepticism here. At least we now know for sure the skills required of NPR reporters.

I have often joked how when we have a political debate after we watch the candidates stake out various claims and positions, we then see reporters talk about their body language. They tell us who looked confident and sincere and who seemed cautious or in other ways unsteady.

This is infuriating because this is exactly the area in which reporters have no comparative advantage over the people viewing the debate. We all engage in conversations and negotiations with people in our everyday life. Most of us are used to assessing the sincerity and integrity of the people we deal with. When we are watching politicians put forward their case on television we can all judge their sincerity and confidence. There is no particular reason to believe that the reporters giving their commentary can do a better job at this than the rest of the people watching the debate.

On the other hand, the reporters could, in principle, know more about the truth of the politicians’ claims. They could know about the background to their policy proposals, where they have been tried, and the issues that have been raised by various experts. Reporters almost invariably fail to provide this sort of analysis, which would be a useful service to their audience.

Anyhow, we got a full and explicit example of the body language treatment this morning on National Public Radio. Their discussion of the meeting between French President Emmanuel Macron and Donald Trump explicitly focused on the body language between the two leaders and assured us that they have struck up a genuine friendship.

I didn’t have a chance to see the events on television, but let me record my skepticism here. At least we now know for sure the skills required of NPR reporters.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Several news outlets have reported that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) does not accept the Trump administration’s claims that its program will lead to a big surge in growth. It is worth mentioning in reference to this dispute that the “robots will take all the jobs” gang agrees with Trump in this dispute. Many people in the debate are probably not aware of this fact because it requires an understanding of third-grade arithmetic.

Economic growth is the sum of labor force growth and productivity growth. There is not too much dispute about the rate of growth of the labor force over the next decade, since it is mostly due to population growth. Apart from large changes in immigration policy, we can’t do much about the number of working-age people who will be in the U.S. over the next decade.

The main question in projecting economic growth is therefore the rate of productivity growth. CBO essentially projects that the slowdown of the last decade will persist, with productivity growth averaging roughly 1.5 percent annually. The Trump crew is betting on a more rapid pace of productivity growth, as are the robots will take all the jobs gang. After all, robots taking the jobs of workers is pretty much the definition of productivity growth.

So, there are many reasons for mocking Trump and his administration, but if any of the robots will take the jobs gang mock the Trump growth projections, they are showing their ignorance. They agree with Trump’s projections of more rapid growth, they are just too confused about the arithmetic and economics to know it.

Several news outlets have reported that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) does not accept the Trump administration’s claims that its program will lead to a big surge in growth. It is worth mentioning in reference to this dispute that the “robots will take all the jobs” gang agrees with Trump in this dispute. Many people in the debate are probably not aware of this fact because it requires an understanding of third-grade arithmetic.

Economic growth is the sum of labor force growth and productivity growth. There is not too much dispute about the rate of growth of the labor force over the next decade, since it is mostly due to population growth. Apart from large changes in immigration policy, we can’t do much about the number of working-age people who will be in the U.S. over the next decade.

The main question in projecting economic growth is therefore the rate of productivity growth. CBO essentially projects that the slowdown of the last decade will persist, with productivity growth averaging roughly 1.5 percent annually. The Trump crew is betting on a more rapid pace of productivity growth, as are the robots will take all the jobs gang. After all, robots taking the jobs of workers is pretty much the definition of productivity growth.

So, there are many reasons for mocking Trump and his administration, but if any of the robots will take the jobs gang mock the Trump growth projections, they are showing their ignorance. They agree with Trump’s projections of more rapid growth, they are just too confused about the arithmetic and economics to know it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney had a Wall Street Journal column highlighting the benefits of “MAGAnomics.” The piece can best be described as a combination of Groundhog Day and outright lies.

In terms of Groundhog Day, we have actually tried MAGAnomics twice before and it didn’t work. We had huge cuts in taxes and regulation under both President Reagan and George W. Bush. In neither case, was there any huge uptick in growth and investment. In fact, the Bush years were striking for the weak growth in the economy and especially the labor market. We saw what was at the time the longest period without net job growth since the Great Depression. And of course, his policy of giving finance free rein gave us the housing bubble and the Great Recession.

The story of the 1980s was somewhat better but hardly follows the MAGAnomics script. The economy did bounce back in 1983, following a steep recession in 1981–1982. That is generally what economies do following steep recessions that were not caused by collapsed asset bubbles. Furthermore, the bounceback was based on increased consumption, not investment as the MAGAnomics folks claim. In fact, investment in the late 1980s fell to extraordinarily low levels. It is also worth pointing out that following both tax cuts, the deficit exploded, just as conventional economics predicts.

By contrast, Clinton raised taxes in 1993 and the economy subsequently soared. It would be silly to attribute the strong growth of the 1990s to the Clinton tax increase; other factors like an IT driven productivity boom and the stock bubble were the key factors, but obviously, the tax increase did not prevent strong growth.

The outright lies part stem from the comparison to prior periods’ growth rates. Mulvaney notes that the 2.0 percent growth rate projected for the next decade is markedly lower than the 3.5 percent rate that we had seen for most of the post-World War II era.This comparison doesn’t make sense.

We are now seeing very slow labor force growth due to the retirement of the baby boom cohort and the fact that the secular rise in the female labor force participation rate is largely at an end. MAGAnomics can do nothing about either of these facts. Slower labor force growth translates into slower overall growth.

Mulvaney also complains about government benefits keeping people from working. The idea that large numbers of people aren’t working because of the generosity of welfare benefits shows a startling degree of ignorance. The United States has the least generous welfare state of any wealthy country, yet we also have among the lowest labor force participation rates. The idea that we will get any substantial boost to the labor force from gutting benefits further is absurd on its face.

Mulvaney apparently missed the fact that energy prices have plummeted in the last three years. Oil had been over $100 a barrel, today it is less than $50. While it is always possible that it could fall still further, any boost to the economy from further declines will be trivial compared to what we have seen already. It would be amazing if Mulvaney was ignorant of the recent path in energy prices.

In short, there is nothing here at all. Mulvaney has given us absolutely zero reason that Trump’s policies will lead to anything other than larger deficits, fewer people with health care, more dangerous workplaces, and a dirtier environment.

Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney had a Wall Street Journal column highlighting the benefits of “MAGAnomics.” The piece can best be described as a combination of Groundhog Day and outright lies.

In terms of Groundhog Day, we have actually tried MAGAnomics twice before and it didn’t work. We had huge cuts in taxes and regulation under both President Reagan and George W. Bush. In neither case, was there any huge uptick in growth and investment. In fact, the Bush years were striking for the weak growth in the economy and especially the labor market. We saw what was at the time the longest period without net job growth since the Great Depression. And of course, his policy of giving finance free rein gave us the housing bubble and the Great Recession.

The story of the 1980s was somewhat better but hardly follows the MAGAnomics script. The economy did bounce back in 1983, following a steep recession in 1981–1982. That is generally what economies do following steep recessions that were not caused by collapsed asset bubbles. Furthermore, the bounceback was based on increased consumption, not investment as the MAGAnomics folks claim. In fact, investment in the late 1980s fell to extraordinarily low levels. It is also worth pointing out that following both tax cuts, the deficit exploded, just as conventional economics predicts.

By contrast, Clinton raised taxes in 1993 and the economy subsequently soared. It would be silly to attribute the strong growth of the 1990s to the Clinton tax increase; other factors like an IT driven productivity boom and the stock bubble were the key factors, but obviously, the tax increase did not prevent strong growth.

The outright lies part stem from the comparison to prior periods’ growth rates. Mulvaney notes that the 2.0 percent growth rate projected for the next decade is markedly lower than the 3.5 percent rate that we had seen for most of the post-World War II era.This comparison doesn’t make sense.

We are now seeing very slow labor force growth due to the retirement of the baby boom cohort and the fact that the secular rise in the female labor force participation rate is largely at an end. MAGAnomics can do nothing about either of these facts. Slower labor force growth translates into slower overall growth.

Mulvaney also complains about government benefits keeping people from working. The idea that large numbers of people aren’t working because of the generosity of welfare benefits shows a startling degree of ignorance. The United States has the least generous welfare state of any wealthy country, yet we also have among the lowest labor force participation rates. The idea that we will get any substantial boost to the labor force from gutting benefits further is absurd on its face.

Mulvaney apparently missed the fact that energy prices have plummeted in the last three years. Oil had been over $100 a barrel, today it is less than $50. While it is always possible that it could fall still further, any boost to the economy from further declines will be trivial compared to what we have seen already. It would be amazing if Mulvaney was ignorant of the recent path in energy prices.

In short, there is nothing here at all. Mulvaney has given us absolutely zero reason that Trump’s policies will lead to anything other than larger deficits, fewer people with health care, more dangerous workplaces, and a dirtier environment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Aaron Carroll had an interesting Upshot piece comparing the merits of Medicaid and private insurance. It focuses on the fact that Medicaid is largely free for beneficiaries, while private insurance typically has substantial co-pays and deductibles. The piece points out that these fees can provide a substantial disincentive for getting health care, especially for lower income people.

While this might be a good way to save the system money if it discourages unnecessary care, which was a major reason the Affordable Care Act encouraged such fees, research shows that people also put off necessary care as a result of such fees. As a result, private insurance may end up leading to worse health outcomes than Medicaid for many low- and moderate-income people.

While this discussion is useful, there is another aspect to the fees that it ignores. Insurers often make mistakes which require patients to spend many extra hours pursuing claims. In many cases, they may not be compensated for care which should be covered if they don’t spend the necessary time. Even if they do get compensated, this is a needless waste of people’s time which is not factored into standard analysis on health care costs.

While it is always dangerous to generalize from very personal experiences, my guess is that my wife and I had to follow up in some manner on at least 20 percent of our claims. In some cases, this could be a single phone call, in other cases it could mean extensive back and forth between the provider and insurer, requiring multiple documents and authorizations. It is hard to believe that our experience is all that atypical or that we are especially bad at filling out forms. (My wife is also an economist who is pretty good at dealing with forms and numbers.)

Anyhow, this is an aspect of co-pays and deductibles that can be especially annoying to patients. Remember, people are most likely to be dealing with large numbers of claims when they are suffering from a health problem. This is not the best time to add another problem to their life.

Aaron Carroll had an interesting Upshot piece comparing the merits of Medicaid and private insurance. It focuses on the fact that Medicaid is largely free for beneficiaries, while private insurance typically has substantial co-pays and deductibles. The piece points out that these fees can provide a substantial disincentive for getting health care, especially for lower income people.

While this might be a good way to save the system money if it discourages unnecessary care, which was a major reason the Affordable Care Act encouraged such fees, research shows that people also put off necessary care as a result of such fees. As a result, private insurance may end up leading to worse health outcomes than Medicaid for many low- and moderate-income people.

While this discussion is useful, there is another aspect to the fees that it ignores. Insurers often make mistakes which require patients to spend many extra hours pursuing claims. In many cases, they may not be compensated for care which should be covered if they don’t spend the necessary time. Even if they do get compensated, this is a needless waste of people’s time which is not factored into standard analysis on health care costs.

While it is always dangerous to generalize from very personal experiences, my guess is that my wife and I had to follow up in some manner on at least 20 percent of our claims. In some cases, this could be a single phone call, in other cases it could mean extensive back and forth between the provider and insurer, requiring multiple documents and authorizations. It is hard to believe that our experience is all that atypical or that we are especially bad at filling out forms. (My wife is also an economist who is pretty good at dealing with forms and numbers.)

Anyhow, this is an aspect of co-pays and deductibles that can be especially annoying to patients. Remember, people are most likely to be dealing with large numbers of claims when they are suffering from a health problem. This is not the best time to add another problem to their life.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Senator Toomey is apparently too young to remember the financial crisis that resulted from the collapse of the housing bubble. He told the Washington Post that he thinks Medicare cost increases will lead to a financial crisis:

“‘It’s a guaranteed financial crisis if we don’t do something about our entitlement programs,’ said Sen. Patrick J. Toomey (R-Pa.), who has pushed for indexing Medicaid to a lower inflation rate. ‘It’s not a question of whether that happens, it’s just a question of when, and how devastating, that is.'”

While it is possible to see how higher Medicare costs would lead to larger budget deficits, if Toomey and his Republican colleagues decide never to raise taxes or cut other spending, there is no obvious way that this leads to a financial crisis. The last crisis came about because a housing bubble was fueled by loans. When housing prices collapsed, trillions of dollars in loans went bad. While this is a fairly straightforward story, it is very difficult to see how rising Medicare costs are more likely to lead to a financial crisis than a Superbowl victory by the Cleveland Browns.

It might have been helpful to point out to readers that the Senator doesn’t appear to know what he is talking about.

Senator Toomey is apparently too young to remember the financial crisis that resulted from the collapse of the housing bubble. He told the Washington Post that he thinks Medicare cost increases will lead to a financial crisis:

“‘It’s a guaranteed financial crisis if we don’t do something about our entitlement programs,’ said Sen. Patrick J. Toomey (R-Pa.), who has pushed for indexing Medicaid to a lower inflation rate. ‘It’s not a question of whether that happens, it’s just a question of when, and how devastating, that is.'”

While it is possible to see how higher Medicare costs would lead to larger budget deficits, if Toomey and his Republican colleagues decide never to raise taxes or cut other spending, there is no obvious way that this leads to a financial crisis. The last crisis came about because a housing bubble was fueled by loans. When housing prices collapsed, trillions of dollars in loans went bad. While this is a fairly straightforward story, it is very difficult to see how rising Medicare costs are more likely to lead to a financial crisis than a Superbowl victory by the Cleveland Browns.

It might have been helpful to point out to readers that the Senator doesn’t appear to know what he is talking about.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión