Neil Irwin examined recent patterns in wage growth in an NYT Upshot piece. Irwin noted the extraordinarily low 0.6 percent pace of productivity growth in recent years (where are the robots?) and argued that wage growth has actually been relatively fast. He then examines why productivity growth might be so slow.

One explanation he left out is that low wages make it possible to hire workers at low productivity jobs. If an employer only has to pay a worker the $7.25 federal minimum wage, then it can be profitable to hire the worker at jobs that increase revenue for the employer by just over $7.25 an hour. This can mean hiring someone to work the midnight shift at a convenience store or to work as a greeter at Walmart.

If the employer had to instead pay a worker $10 or $12 an hour, then many very low productivity jobs would no longer exist. This would raise the average level of productivity in the economy by eliminating the least productive jobs.

In this way, it is possible that the weakness of the labor market has been a factor in reducing productivity growth as workers have had no choice but to take low paying, low productivity jobs. If this is true, as the labor market tightens and wages start to grow more rapidly, we should see productivity increase more rapidly.

Neil Irwin examined recent patterns in wage growth in an NYT Upshot piece. Irwin noted the extraordinarily low 0.6 percent pace of productivity growth in recent years (where are the robots?) and argued that wage growth has actually been relatively fast. He then examines why productivity growth might be so slow.

One explanation he left out is that low wages make it possible to hire workers at low productivity jobs. If an employer only has to pay a worker the $7.25 federal minimum wage, then it can be profitable to hire the worker at jobs that increase revenue for the employer by just over $7.25 an hour. This can mean hiring someone to work the midnight shift at a convenience store or to work as a greeter at Walmart.

If the employer had to instead pay a worker $10 or $12 an hour, then many very low productivity jobs would no longer exist. This would raise the average level of productivity in the economy by eliminating the least productive jobs.

In this way, it is possible that the weakness of the labor market has been a factor in reducing productivity growth as workers have had no choice but to take low paying, low productivity jobs. If this is true, as the labor market tightens and wages start to grow more rapidly, we should see productivity increase more rapidly.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post printed a Reuters article that included a major mistake in economics. The piece is about the plotting of conservative politicians and business leaders trying to plan for the likelihood that their ally, President Michel Temer, will be indicted and removed from office for corruption. It told readers:

“Amid the political turmoil that comes just a year after his predecessor was impeached and removed from office, preserving Temer’s agenda of austerity reforms and pulling Brazil’s economy out of recession is more important than saving the leader himself, sources in three parties that are his main allies said.”

Actually, this statement is contradictory. The austerity is one of the main causes of the recession. If they want to pull the economy out of recession then they should be reversing the austerity. Hopefully, Mr. Temer’s allies understand this and it is just the Reuters’ reporter who is confused.

The next sentence added:

“Those measures range from reducing a gaping budget deficit through opening doors to foreign investors to weakening labor laws and tightening pensions.”

Readers may have been confused by the phrase “tightening pensions.” The normal English translation would have been “cutting pensions.” It is understandable that politicians who are trying to pursue policies that are unpopular may use euphemisms to conceal their agenda. It is not clear why Reuters or the Post would.

The Washington Post printed a Reuters article that included a major mistake in economics. The piece is about the plotting of conservative politicians and business leaders trying to plan for the likelihood that their ally, President Michel Temer, will be indicted and removed from office for corruption. It told readers:

“Amid the political turmoil that comes just a year after his predecessor was impeached and removed from office, preserving Temer’s agenda of austerity reforms and pulling Brazil’s economy out of recession is more important than saving the leader himself, sources in three parties that are his main allies said.”

Actually, this statement is contradictory. The austerity is one of the main causes of the recession. If they want to pull the economy out of recession then they should be reversing the austerity. Hopefully, Mr. Temer’s allies understand this and it is just the Reuters’ reporter who is confused.

The next sentence added:

“Those measures range from reducing a gaping budget deficit through opening doors to foreign investors to weakening labor laws and tightening pensions.”

Readers may have been confused by the phrase “tightening pensions.” The normal English translation would have been “cutting pensions.” It is understandable that politicians who are trying to pursue policies that are unpopular may use euphemisms to conceal their agenda. It is not clear why Reuters or the Post would.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s the question the board of directors of Charter should be asking, but I suspect they never do. The company scored first in the NYT’s annual compilation of CEO pay packages, coming in almost $30 million ahead of CBS, which is number 2. Of course, if the CEOs earned less than the other top people in the corporate hierarchy would likely get smaller paychecks as well. And, it might be harder for the presidents of universities, foundations, and non-profits to explain the need for seven figure salaries for their work.

It seems unlikely that directors ever push in a big way for lower pay for CEOs because they have almost no incentive to do so. More than 99 percent of the directors put up for re-election are approved by shareholders. This is because it is very difficult to organize among shareholders to unseat a director. (Think of the difficulty of unseating an incumbent member of Congress and multiply by about 100.)

As a result, there is no reason to raise unpleasant questions at board meetings. Even though they are supposed to serve shareholders, which means not paying one penny more than necessary to CEOs and top management for their performance (just as CEOs try to pay workers as little as possible), their incentive is to get along with top management. The result is the upward spiral in CEO pay that we have seen in the last four decades.

A big part of the problem is that asset managers (think Vanguard and Blackrock) routinely support management slates as they vote trillions (literally) of dollars worth of stock held by people in their 401(k)s and IRAs. These asset managers care more about staying on good terms with top management than making sure they aren’t overpaid. This creates a structure where ridiculously rich CEOs, who are usually big celebrants of the market, are effectively shielded themselves from market discipline. Isn’t that the way markets are supposed to work?

That’s the question the board of directors of Charter should be asking, but I suspect they never do. The company scored first in the NYT’s annual compilation of CEO pay packages, coming in almost $30 million ahead of CBS, which is number 2. Of course, if the CEOs earned less than the other top people in the corporate hierarchy would likely get smaller paychecks as well. And, it might be harder for the presidents of universities, foundations, and non-profits to explain the need for seven figure salaries for their work.

It seems unlikely that directors ever push in a big way for lower pay for CEOs because they have almost no incentive to do so. More than 99 percent of the directors put up for re-election are approved by shareholders. This is because it is very difficult to organize among shareholders to unseat a director. (Think of the difficulty of unseating an incumbent member of Congress and multiply by about 100.)

As a result, there is no reason to raise unpleasant questions at board meetings. Even though they are supposed to serve shareholders, which means not paying one penny more than necessary to CEOs and top management for their performance (just as CEOs try to pay workers as little as possible), their incentive is to get along with top management. The result is the upward spiral in CEO pay that we have seen in the last four decades.

A big part of the problem is that asset managers (think Vanguard and Blackrock) routinely support management slates as they vote trillions (literally) of dollars worth of stock held by people in their 401(k)s and IRAs. These asset managers care more about staying on good terms with top management than making sure they aren’t overpaid. This creates a structure where ridiculously rich CEOs, who are usually big celebrants of the market, are effectively shielded themselves from market discipline. Isn’t that the way markets are supposed to work?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Ever since the Trump administration released its budget on Tuesday, economists (including me) have been ridiculing its assumption that we will see an average annual growth rate of 3.0 percent over the next decade. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects an average growth rate of just under 1.9 percent for this period. This projection assumes slow labor force growth, as the baby boom cohort retires, and a continuation of the weak productivity growth we have seen over the last decade.

The Trump administration’s 3.0 percent growth number presumably assumes that productivity growth will rebound to something like the 3.0 percent growth rate we saw in the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973 and again from 1995 to 2005. It seems that Mark Zuckerberg agrees with the Trump administration’s assessment since, according to the Washington Post, he warned of massive job loss due to technology in the years ahead and the need to have something like a universal basic income to ensure that people have enough money to survive.

If we continue to see the rates of productivity growth experienced in recent years and projected going forward by CBO, we will be seeing a labor shortage, not a shortage of jobs. So Mr. Zuckerberg, along with the Trump administration, has a very different view of the future than most of the economics profession (which doesn’t mean they are wrong).

Ever since the Trump administration released its budget on Tuesday, economists (including me) have been ridiculing its assumption that we will see an average annual growth rate of 3.0 percent over the next decade. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects an average growth rate of just under 1.9 percent for this period. This projection assumes slow labor force growth, as the baby boom cohort retires, and a continuation of the weak productivity growth we have seen over the last decade.

The Trump administration’s 3.0 percent growth number presumably assumes that productivity growth will rebound to something like the 3.0 percent growth rate we saw in the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973 and again from 1995 to 2005. It seems that Mark Zuckerberg agrees with the Trump administration’s assessment since, according to the Washington Post, he warned of massive job loss due to technology in the years ahead and the need to have something like a universal basic income to ensure that people have enough money to survive.

If we continue to see the rates of productivity growth experienced in recent years and projected going forward by CBO, we will be seeing a labor shortage, not a shortage of jobs. So Mr. Zuckerberg, along with the Trump administration, has a very different view of the future than most of the economics profession (which doesn’t mean they are wrong).

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

As we know, the goal of the Trump administration is to redistribute as much income as quickly as possible to his family, friends, and people like his family and friends. This is why the centerpiece of his health care reform is more than $600 billion in tax cuts over the next decade that will go overwhelmingly to the richest one percent of the population.

But there is a flip side to these cuts. If the government is spending less money on health care, then the corporations and wealthy individuals who get their income from the health care sector will be seeing less money. Fortunately, the American Health Care Act of 2017 is designed to minimize this problem.

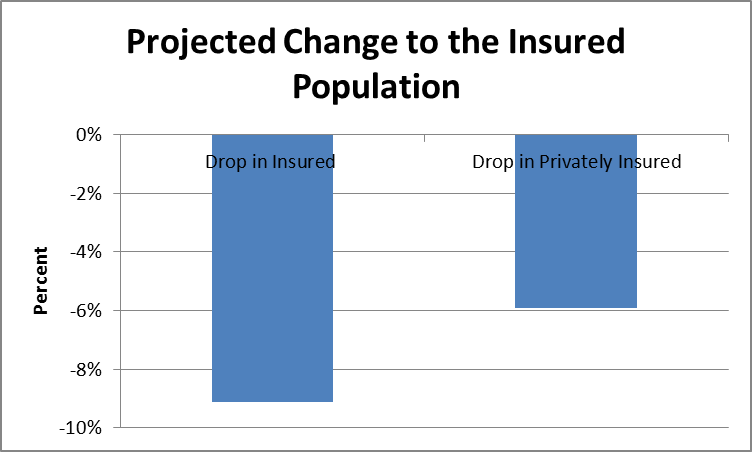

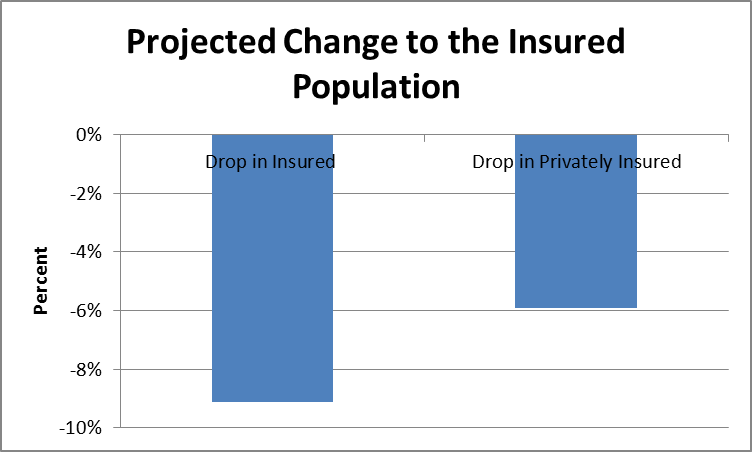

While it will reduce the percentage of insured among the under 65 population by 9.1 percentage points, according to the analysis from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), it will only reduce the percentage of the under 65 who are privately insured by 5.9 percent.[1]

Source: CBO 2017 and CBO 2012.

This means that if we assume the reduction in payments to private insurers are proportionate to the reduction in enrollment, insurers will see a loss of roughly $24 billion in net revenue (premiums minus payments to providers) in 2026 even though total government spending on the AHCA and Medicaid will be down by $156 billion in that year. This means that, even though insurance companies will get somewhat less money as a result of the AHCA, the Republicans have shielded them from the worst effects of the spending reduction.

[1] These numbers are taken from Table 4, the total insured population is derived from CBO (2012), Table 3, with the assumption that the percentages of publicly and privately insured would stay the same from the last year in that analysis (2022) until 2026.

As we know, the goal of the Trump administration is to redistribute as much income as quickly as possible to his family, friends, and people like his family and friends. This is why the centerpiece of his health care reform is more than $600 billion in tax cuts over the next decade that will go overwhelmingly to the richest one percent of the population.

But there is a flip side to these cuts. If the government is spending less money on health care, then the corporations and wealthy individuals who get their income from the health care sector will be seeing less money. Fortunately, the American Health Care Act of 2017 is designed to minimize this problem.

While it will reduce the percentage of insured among the under 65 population by 9.1 percentage points, according to the analysis from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), it will only reduce the percentage of the under 65 who are privately insured by 5.9 percent.[1]

Source: CBO 2017 and CBO 2012.

This means that if we assume the reduction in payments to private insurers are proportionate to the reduction in enrollment, insurers will see a loss of roughly $24 billion in net revenue (premiums minus payments to providers) in 2026 even though total government spending on the AHCA and Medicaid will be down by $156 billion in that year. This means that, even though insurance companies will get somewhat less money as a result of the AHCA, the Republicans have shielded them from the worst effects of the spending reduction.

[1] These numbers are taken from Table 4, the total insured population is derived from CBO (2012), Table 3, with the assumption that the percentages of publicly and privately insured would stay the same from the last year in that analysis (2022) until 2026.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT left this off the list of possible solutions in an article on China’s rapidly growing private-sector debt. The basic story is a simple one. Creditors are given an equity stake in a company in exchange for reducing or eliminating the company’s debt liability. In a rapidly growing economy like China’s, there is no obvious reason this cannot be done on a large-scale, thereby radically reducing debt liabilities.

The NYT left this off the list of possible solutions in an article on China’s rapidly growing private-sector debt. The basic story is a simple one. Creditors are given an equity stake in a company in exchange for reducing or eliminating the company’s debt liability. In a rapidly growing economy like China’s, there is no obvious reason this cannot be done on a large-scale, thereby radically reducing debt liabilities.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Washington Post columnist Charles Lane is a devout proponent of the policy of selective protectionism. Under this policy, which is called “free trade” for marketing purposes, the wages of U.S. manufacturing workers and non-college educated workers more generally are pushed down by placing them in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world.

By contrast, highly paid professionals like doctors and dentists are able to achieve gains in wages by keeping in place the barriers that protect them from similar competition. In addition, drug companies, medical equipment companies, and software companies benefit from ever longer and stronger patent and copyright protection.

This selective protectionism is a key part of the upward redistribution of the last four decades. (Yes, this is the story of my book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer [it’s free].) Anyhow, Lane is apparently upset that Donald Trump and much of the public seem to be rejecting this policy of selective protectionism so he used the 100th anniversary of John Kennedy’s birth to enlist him in the cause.

As Lane tells it, John Kennedy proclaimed:

“Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do to make the rich even richer.”

Washington Post columnist Charles Lane is a devout proponent of the policy of selective protectionism. Under this policy, which is called “free trade” for marketing purposes, the wages of U.S. manufacturing workers and non-college educated workers more generally are pushed down by placing them in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world.

By contrast, highly paid professionals like doctors and dentists are able to achieve gains in wages by keeping in place the barriers that protect them from similar competition. In addition, drug companies, medical equipment companies, and software companies benefit from ever longer and stronger patent and copyright protection.

This selective protectionism is a key part of the upward redistribution of the last four decades. (Yes, this is the story of my book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer [it’s free].) Anyhow, Lane is apparently upset that Donald Trump and much of the public seem to be rejecting this policy of selective protectionism so he used the 100th anniversary of John Kennedy’s birth to enlist him in the cause.

As Lane tells it, John Kennedy proclaimed:

“Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do to make the rich even richer.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had an article reporting on the fact that President Trump’s hotels have not been consistently screening payments from foreign governments to donate to charities, as he had promised in order to comply with the constitutional ban on such payments. The article cites a document from the Trump Organization saying that it would be impractical to screen all their guests to determine which ones were representatives of foreign governments.

While this sort of screening may exceed the competency of the Trump Organization, there is an extremely simply route that would allow Mr. Trump to comply with the law. He can sell his assets and place them in a blind trust. This can quickly be done in a way that need not involve a rushed sale of assets.

It is understandable that Trump may not want to sell his business empire, but this is the sort of thing that we expect adults to think about before they take a job. If the business is so valuable to him, then he should not have run for president.

The Washington Post had an article reporting on the fact that President Trump’s hotels have not been consistently screening payments from foreign governments to donate to charities, as he had promised in order to comply with the constitutional ban on such payments. The article cites a document from the Trump Organization saying that it would be impractical to screen all their guests to determine which ones were representatives of foreign governments.

While this sort of screening may exceed the competency of the Trump Organization, there is an extremely simply route that would allow Mr. Trump to comply with the law. He can sell his assets and place them in a blind trust. This can quickly be done in a way that need not involve a rushed sale of assets.

It is understandable that Trump may not want to sell his business empire, but this is the sort of thing that we expect adults to think about before they take a job. If the business is so valuable to him, then he should not have run for president.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times ran a column by Maya MacGuineas, the president of the Peter Peterson-backed Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The piece begins with the ominous announcement:

“President Trump entered office facing the worst ratio of debt to gross domestic product of any new president in American history except Harry Truman — an onerous 77 percent.”

It could have also begun with the announcement that the ratio of debt service (interest on the debt, net of payments from the Federal Reserve Board) to GDP is less than one percent. This contrasts with a ratio of almost 3.0 percent in the early and mid-1990s. Are you scared yet?

Actually, you should be. Folks like Ms. MacGuineas have pushed austerity policies in the United States and around the world for the last decade. These policies have prevented the government from spending the amount necessary to restore the economy to full employment. This has not only kept millions of people in the United States from having jobs, it has prevented tens of millions from getting pay increases by weakening their bargaining power.

Furthermore, the lower levels of output have an enduring impact on the economy. They are associated with less investment in public and private capital and less money spent on research and development. In addition, unemployed workers don’t gain the experience they would have otherwise. Many of the long-term unemployed drop out of the labor force and may end up never working again.

As a result of these effects, the Congressional Budget Office now estimates that the economy’s potential level of output for 2017 is 10 percent less than what it had projected for 2017 back in 2008 before the Great Recession really took hold. The loss in output due to this austerity tax is roughly $2 trillion a year. This is the reduction in wages and profit income as a result of the smaller size of the economy. That comes to $6,000 per person per year.

This is the burden that the Peter Peterson crew have imposed on our children and grandchildren due to their scare tactics on the deficits. (Hey, remember the Reinhart-Rogoff 90 percent debt to GDP cliff?) And fans of logic everywhere know that it will not matter one iota to our kids’ well-being if the government were to increase taxes on each of them by $6,000 or whether its austerity policies lead them to earn $6,000 less each year.

Unfortunately, because of the distribution of money and power in society, it is only the taxes that will draw attention. The fact that inept economic management needlessly caused us to sacrifice economic growth, and did so in a way that disproportionately hurt the poor and middle class, is considered rude to mention in polite company.

Instead, we get columns with meaningless figures about debt to GDP that are designed to scare people.

Addendum:

I somehow forget to mention the rents from government-granted patent and copyright monopolies. As I point out in Rigged, these come to close to $400 billion a year in the case of prescription drugs alone. This is the difference between the patent-protected price and the free market price. It is effectively a privately collected tax. If we add in the rents from medical equipment, software, and other items the figure could easily be twice as high. In other words, we are making our kids pay $400 billion to $800 billion a year to pay for the research and creative work that was done in the past.

Anyone seriously concerned about the burden we impose on our kids has to include this cost in their calculations. Otherwise, they just deserve to have their pronouncements treated with ridicule.

The New York Times ran a column by Maya MacGuineas, the president of the Peter Peterson-backed Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The piece begins with the ominous announcement:

“President Trump entered office facing the worst ratio of debt to gross domestic product of any new president in American history except Harry Truman — an onerous 77 percent.”

It could have also begun with the announcement that the ratio of debt service (interest on the debt, net of payments from the Federal Reserve Board) to GDP is less than one percent. This contrasts with a ratio of almost 3.0 percent in the early and mid-1990s. Are you scared yet?

Actually, you should be. Folks like Ms. MacGuineas have pushed austerity policies in the United States and around the world for the last decade. These policies have prevented the government from spending the amount necessary to restore the economy to full employment. This has not only kept millions of people in the United States from having jobs, it has prevented tens of millions from getting pay increases by weakening their bargaining power.

Furthermore, the lower levels of output have an enduring impact on the economy. They are associated with less investment in public and private capital and less money spent on research and development. In addition, unemployed workers don’t gain the experience they would have otherwise. Many of the long-term unemployed drop out of the labor force and may end up never working again.

As a result of these effects, the Congressional Budget Office now estimates that the economy’s potential level of output for 2017 is 10 percent less than what it had projected for 2017 back in 2008 before the Great Recession really took hold. The loss in output due to this austerity tax is roughly $2 trillion a year. This is the reduction in wages and profit income as a result of the smaller size of the economy. That comes to $6,000 per person per year.

This is the burden that the Peter Peterson crew have imposed on our children and grandchildren due to their scare tactics on the deficits. (Hey, remember the Reinhart-Rogoff 90 percent debt to GDP cliff?) And fans of logic everywhere know that it will not matter one iota to our kids’ well-being if the government were to increase taxes on each of them by $6,000 or whether its austerity policies lead them to earn $6,000 less each year.

Unfortunately, because of the distribution of money and power in society, it is only the taxes that will draw attention. The fact that inept economic management needlessly caused us to sacrifice economic growth, and did so in a way that disproportionately hurt the poor and middle class, is considered rude to mention in polite company.

Instead, we get columns with meaningless figures about debt to GDP that are designed to scare people.

Addendum:

I somehow forget to mention the rents from government-granted patent and copyright monopolies. As I point out in Rigged, these come to close to $400 billion a year in the case of prescription drugs alone. This is the difference between the patent-protected price and the free market price. It is effectively a privately collected tax. If we add in the rents from medical equipment, software, and other items the figure could easily be twice as high. In other words, we are making our kids pay $400 billion to $800 billion a year to pay for the research and creative work that was done in the past.

Anyone seriously concerned about the burden we impose on our kids has to include this cost in their calculations. Otherwise, they just deserve to have their pronouncements treated with ridicule.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Nope, that is not what the Washington Post said, instead it insisted to readers that the opposite is the case. The first sentence of a front page article on the Trump administration’s infrastructure plans told readers:

“The Trump administration, determined to overhaul and modernize the nation’s infrastructure, is drafting plans to privatize some public assets such as airports, bridges, highway rest stops and other facilities, according to top officials and advisers.”

I guess this is another case where we are relying on the extraordinary mind-reading skills of reporters, since the rest of us would not know that the administration is pursuing privatization plans because it is “determined to overhaul and modernize the nation’s infrastructure,” as opposed to making the Trump family and people like them even richer. The evidence of past privatizations might suggest the opposite.

While the piece does note some of the past failures of privatization projects, the framing in the first sentence attributes good faith in its motives which there is zero reason to assume. It is certainly possible that the Trump administration is acting in what it perceives to be the public good but it is also entirely possible that it is trying to further enrich a small group of wealthy people at the expense of everyone else.

The Post has no basis for its assertion that Trump administration actually gives a damn about the public interest.

Nope, that is not what the Washington Post said, instead it insisted to readers that the opposite is the case. The first sentence of a front page article on the Trump administration’s infrastructure plans told readers:

“The Trump administration, determined to overhaul and modernize the nation’s infrastructure, is drafting plans to privatize some public assets such as airports, bridges, highway rest stops and other facilities, according to top officials and advisers.”

I guess this is another case where we are relying on the extraordinary mind-reading skills of reporters, since the rest of us would not know that the administration is pursuing privatization plans because it is “determined to overhaul and modernize the nation’s infrastructure,” as opposed to making the Trump family and people like them even richer. The evidence of past privatizations might suggest the opposite.

While the piece does note some of the past failures of privatization projects, the framing in the first sentence attributes good faith in its motives which there is zero reason to assume. It is certainly possible that the Trump administration is acting in what it perceives to be the public good but it is also entirely possible that it is trying to further enrich a small group of wealthy people at the expense of everyone else.

The Post has no basis for its assertion that Trump administration actually gives a damn about the public interest.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión